Bear worship (also known as the bear cult or arctolatry) is the religious practice of the worshipping of bears found in many North Eurasian ethnic religions such as among the Sami, Nivkh, Ainu,[1] Basques, Germanic peoples, Slavs and Finns.[2] There are also a number of deities from Celtic Gaul and Britain associated with the bear, and the Dacians, Thracians, and Getians were noted to worship bears and annually celebrate the bear dance festival. The bear is featured on many totems throughout northern cultures that carve them.[3]

Ursine ancestor

In an article in Enzyklopädie des Märchens, American folklorist Donald J. Ward noted that a story about a bear mating with a human woman, and producing a male heir, functions as an ancestor myth to peoples of the northern hemisphere, namely, from North America, Japan, China, Siberia and Northern Europe.[4]

Paleolithic cult

_(14763072414).jpg.webp)

The existence of an ancient bear cult among Neanderthals in Western Eurasia in the Middle Paleolithic has been a subject of conjecture due to contentious archaeological findings.[3] Evidence suggests that Neanderthals could have worshipped the cave bear (Ursus spelaeus) and bear bones have been discovered in several cave sites across Western Eurasia. It was not just the presence of these bones, but their peculiar arrangement that intrigued archaeologists.[5] During the excavation, on-site archaeologists determined that the bones were arranged in such a way that could only have resulted from hominin intervention rather than natural deposition processes.[5] Emil Bächler, a proponent of the bear-cult hypothesis, found bear remains in Switzerland and at Morn Cave (Mornova zijalka) in Slovenia. Along with Bächler's discovery, bear skulls were found by André Leroi-Gourhan arranged in a perfect circle in Saône-et-Loire.[5] The discovery of patterns such as those found by Leroi-Gourhan suggests that these bear remains were placed in this arrangement intentionally; an act which can only be attributed to Neandertals due to the dating of the site and is interpreted as ritual. [5]

While these findings have been taken to indicate an ancient bear-cult, other interpretations of remains have led others to conclude that the bear bones' presence in these contexts are a natural phenomenon. Ina Wunn, based on the information archaeologists have about early hominins, contends that if Neandertals did worship bears there would be evidence of it in their settlements and camps.[6] However, most bear remains have been found in caves.[6] Many archaeologists now theorise that, since most bear species hibernate in caves during the winter, the presence of bear remains is not unusual in this context [7] Bears which lived inside these caves perished from natural causes such as illness or starvation.[8] Wunn argues that the placement of these remains is due to natural, post-deposition events such as wind, sediment, or water.[9] Therefore, the assortment of bear remains in caves did not result from human activities[10] Certain archaeologists, such as Emil Bächler, continue to use their excavations to support that an ancient bear cult did exist.[11]

Eastern Slavic culture

Bears were the most worshipped animals of Ancient Slavs. During pagan times, it was associated with the god Volos, the patron of domestic animals. Eastern Slavic folklore describes the bear as a totem personifying a male: father, husband, or a fiancé. Legends about turnskin bears appeared, it was believed that humans could be turned into bears for misbehavior.[12]

Altaic peoples

In 1925–1927, Nadezhda Petrovna Dyrenkova made field observations of bear worship among the Altai, Tubalar (Tuba-Kiji), Telengit, and Shortsi of the Kuznetskaja Taiga as well as among the Sagai tribes in the regions of Minusinsk, near the Kuznetskaja Taiga (1927).[13]

Finns

In Finnish paganism, the bear was considered a taboo animal, and the word for "bear" (oksi) was a taboo word. Euphemisms such as mesikämmen "honey-palm" were used instead. The modern Finnish word karhu (from karhea, coarse, rough, referring to its coarse fur) is also such a euphemism. In the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala, the bear is called Otso, which is the sacred king of animals and leader of the forest, deeply feared and respected by old Finnish tribes.[14][15] Calling a bear by its true name was believed to summon the bear. A successful bear hunt was followed by a ritual feast called peijaiset with a ceremony as the bear as an "honoured guest," with songs convincing the bear that its death was "accidental", in order to appease its spirit. The skull of the bear was raised high into a pine tree so its spirit could climb back into its home in the heavens, and this tree was venerated afterwards.

Spain

There are annual bear festivals that take place in various towns and communes in the Pyrenees region.

In Prats de Molló, the Festa de l'ós ("festival of the bear") (also known as dia dels óssos "day of the bears") held on Candlemas (February 2) is a ritual in which men dressed up as bears brandishing sticks terrorize people in the streets.[16] Formerly, the festival centered on the "bears" mock-attacking the women and trying to blacken their breasts (with soot), which seemed scandalous to outside first-time observers. But according to the testimony of someone who remembered the olden days before that, the festival that at Prats de Molló involved elaborate staging, much like the version in Arles.[17]

The Arles version (Festa de l'os d'Arles) involves a female character named Rosetta (Roseta) who gets abducted by the "bear". Rosetta was traditionally played by a man or a boy dressed up as a girl. The "bear" would bring the Rosetta to a hut raised on the center square of town (where the victim would be fed sausages, cake, and white wine). The event finished with the "bear" being shaved and "killed".[18][17]

There is also a similar festival in the town of Sant Llorenç de Cerdans: Festa de l'ós de Sant Llorenç de Cerdans.

These three well-known festivals take place in towns located in Vallespir, and are known as «Festes de l'os al Vallespir» or «El dia de l'os/dels ossos».[17]

Andorra, in an entirely different Pyrenean valley, has some festivals dedicated to the she-bear, known collectively as Festes de l'ossa. These include the Ball de l'ossa ("she-bear's dance") in Encamp, and Última ossa ("the last she-bear") in Ordino.

There is also a bear related festival in the Valencian town of La Mata, named Festa de l'Onso de la Mata.

Korean mythology

According to legend, Ungnyeo (literally "bear woman") was a bear who turned into a woman, and gave birth to Dangun, the founder of the first Korean kingdom, Gojoseon. Bears were revered as motherly figures and symbolized patience.[19]

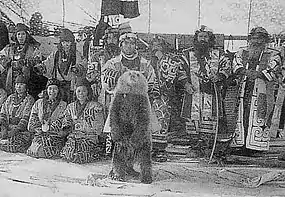

Nivkh people

The bear festival is a religious festival celebrated by the indigenous Nivkh in the Russian Far East. A Nivkh shaman (ch'am) would preside over the Bear Festival, which was celebrated in the winter between January and February, depending on the clan. A bear was captured and raised in a corral for several years by local women, who treated the bear like a child. The bear is considered a sacred earthly manifestation of Nivkh ancestors and the gods in bear form. During the Festival, the bear is dressed in a specially made ceremonial costume and offered a banquet to take back to the realm of gods to show benevolence upon the clans.[20] After the banquet, the bear is killed and eaten in an elaborate religious ceremony. The festival was arranged by relatives to honour the death of a kinsman. The bear's spirit returns to the gods of the mountain 'happy' and rewards the Nivkh with bountiful forests.[21] Generally, the Bear Festival was an inter-clan ceremony where a clan of wife-takers restored ties with a clan of wife-givers upon the broken link of the kinsman's death.[22] The Bear Festival was suppressed in the Soviet period; since then the festival has had a modest revival, albeit as a cultural rather than a religious ceremony.[23]

Ainu bear worship

The Ainu people, who live on select islands in the Japanese archipelago, call the bear “kamuy” in the Ainu language, which translates to mean "god". Many other animals are considered to be gods in the Ainu culture, but the bear is the head of the gods.[24] For the Ainu, when the gods visit the world of man, they don fur and claws and take on the physical appearance of an animal. Usually, however, when the term “kamuy” is used, it essentially means a bear.[24] The Ainu people willingly and thankfully ate the bear as they believed that the disguise (the flesh and fur) of any god was a gift to the home that the god chose to visit.[25][26]

The Ainu believed that the gods on Earth, the world of man, appeared in the form of animals. The gods had the capability of taking human form but only in their home, the country of the gods, which is outside the world of man.[24] To return a god to his country, the people would sacrifice and eat the animal sending the god's spirit away with civility. The ritual was called Omante and usually involveed a deer or adult bear.[25]

Omante occurred when the people sacrificed an adult bear, but when they caught a bear cub, they performed a different ritual which is called Iomante, in the Ainu language, or Kumamatsuri in Japanese. Kumamatsuri translates to "bear festival," and Iomante means "sending off."[27] The event of Kumamatsuri began with the capture of a young bear cub. As if he were a child given by the gods, the cub was fed human food from a carved wooden platter and was treated better than Ainu children for they thought of him as a god.[28] If the cub was too young and lacked the teeth to properly chew food, a nursing mother would let him suckle from her own breast.[28] When the cub reached 2–3 years of age, the cub was taken to the altar and then sacrificed. Usually, Kumamatsuri occurred in midwinter, when the bear meat is the best from the added fat.[28] The villagers would shoot it with both normal and ceremonial arrows, make offerings, dance, and pour wine on top of the cub corpse.[28] The words of sending off for the bear god were then recited. The festival lasted for three days and three nights to properly return the bear god to his home.[28]

See also

- Animal worship

- Arctic

- Arcturus

- Artemis

- Berserker

- Kumaso

- Kalevala

- Rock carvings at Alta

- Shardik (fantasy novel by Richard Adams centered around bear worship)

References

- ↑ Bledsoe, p. 1.

- ↑ Wilfred Bonser (2012) "The Mythology of the Kalevala, with Notes on Bear-Worship Among the Finns.", p. 344

- 1 2 Wunn 2000, pp. 434–435.

- ↑ Ward, Donald. "Bärensohn". In: Enzyklopädie des Märchens Online. Edited by Rolf Wilhelm Brednich, Heidrun Alzheimer, Hermann Bausinger, Wolfgang Brückner, Daniel Drascek, Helge Gerndt, Ines Köhler-Zülch, Klaus Roth and Hans-Jörg Uther. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2016 [1977]. https://www-degruyter-com.wikipedialibrary.idm.oclc.org/database/EMO/entry/emo.1.275/html. Accessed 2022-10-30.

- 1 2 3 4 Wunn 2000, p. 435.

- 1 2 Wunn 2000, p. 436.

- ↑ Wunn 2000, pp. 436–437.

- ↑ Wunn 2000, p. 437.

- ↑ Wunn 2000, pp. 437–438.

- ↑ Wunn 2000, pp. 438.

- ↑ Wunn 2000.

- ↑ "The Most Russian of All Beasts". Archived from the original on 9 July 2019. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ↑ Dyrenkova

- ↑ Väätäinen, Erika (2022-02-28). "Exploring Finnish Mythology Creatures And Finnish Folklore". Scandification. Retrieved 2023-01-26.

- ↑ "The Kalevala: Rune XLVI. Otso the Honey-eater". www.sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 2023-01-26.

- ↑ Webb, Mick (n.d.), Bear Mountain: The battle to save the Pyrenean brown bear, Guardian Books, ISBN 9781783560820

- 1 2 3 Fabre, Daniel (1969), "Recherches sur Jean de l'Ours (2e partie)" (PDF), Folklore: Revue d'ethnographie méridonale, XXII (134): 10–11

- ↑ Crichton, Robin, ed. (2007), Monsieur Mackintosh: the travels and paintings of Charles Rennie Mackintosh in the Pyrénées Orientales, 1923-1927, Luath, p. 41, ISBN 9781905222360

- ↑ "곰". The Academy of Korean Studies. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ↑ Chaussonnet 1995, pp. 35, 81.

- ↑ Sternberg & Grant 1999, p. 160.

- ↑ Chaussonnet 1995, p. 35.

- ↑ Gall 1998, pp. 4–6.

- 1 2 3 Kindaichi & Yoshida 1949, p. 345.

- 1 2 Kindaichi & Yoshida 1949, p. 348.

- ↑ O. Harrassowitz (2007) "Journal of Asian History, Volume 41", p. 134-135

- ↑ Kindaichi & Yoshida 1949, pp. 348–349.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kindaichi & Yoshida 1949, p. 349.

Sources

- Bledsoe, Brandon. "The Significance of the Bear Ritual Among the Sami and Other Northern Cultures". Archived from the original on 9 January 2008.

- Chaussonnet, Valerie (1995). Native Cultures of Alaska and Siberia. Washington, D.C.: Arctic Studies Center. p. 112. ISBN 1-56098-661-1.

- Gall, Timothy L. (1998). Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life. Nivkhs. Detroit, Michigan: Gale: Research Inc. p. 2100. ISBN 0-7876-0552-2.

- Kindaichi, Kyōsuke; Yoshida, Minori (Winter 1949). "The Concepts behind the Ainu Bear Festival (Kumamatsuri)". Southwestern Journal of Anthropology. University of New Mexico. 5 (4): 345–350. doi:10.1086/soutjanth.5.4.3628594. JSTOR 3628594. S2CID 155380619.

- Sternberg, Lev Iakovlevich; Grant, Bruce (1999). The Social Organization of the Gilyak. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-97799-X.

- Wunn, Ina (2000). "Beginning of Religion" (PDF). Numen. 47 (4): 417–452. doi:10.1163/156852700511612. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-12-30. Retrieved 2017-01-18.

Further reading

- Berres, Thomas E., David M. Stothers, and David Mather. "Bear Imagery and Ritual in Northeast North America: An Update and Assessment of A. Irving Hallowell's Work." In: Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology 29, no. 1 (2004): 5-42.

- RYDVING, HÅKAN (2010. “The ‘Bear Ceremonial’ and Bear Rituals Among the Khanty and the Sami”. In Temenos - Nordic Journal of Comparative Religion 46 (1): 31–52.

- Shepard, Paul, and Barry Sanders. “Celebrations of the Bear”. In: North American Review 270, no. 3 (1985): 17–25.

- Young, Steven R. "'Bear' in Baltic". In: Journal of Baltic Studies 22, no. 3 (1991): 241–244.

External links

- Arctolatry Archived 2013-08-17 at the Wayback Machine - A website outlining historical forms of arctolatry throughout the world with maps and timelines.