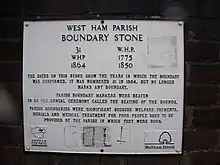

Beating the bounds or perambulating the bounds[1] is an ancient custom still observed in parts of England, Wales, and the New England region of the United States, which traditionally involved swatting local landmarks with branches to maintain a shared mental map of parish boundaries,[2] usually every seven years.[3][4]

These ceremonial events occur on what are sometimes called gangdays; the custom of going a-ganging was kept before the Norman Conquest.[5] During the event, a group of prominent citizens from the community, which can be an English church parish, New England town, or other civil division, will walk the geographic boundaries of their locality for the purpose of maintaining the memory of the precise location of these boundaries. While modern surveying techniques have rendered these ceremonial walks largely irrelevant, the practice remains as an important local civic ceremony or legal requirement for civic leaders.

Ceremony

In former times when maps were rare,[6] it was usual to make a formal perambulation of the parish boundaries on Ascension Day or during Rogation week.[7] Knowledge of the limits of each parish needed to be handed down so that such matters as liability to contribute to the repair of the church or the right to be buried within the churchyard were not disputed. The relevant jurisdiction was that of the ecclesiastical courts.[8] The priest of the parish with the churchwardens and the parochial officials headed a crowd of boys who beat the parish boundary markers with green boughs, usually birch or willow. Sometimes the boys were whipped or violently bumped on the boundary stones to make them remember. The object of taking boys along is supposed to ensure that witnesses to the boundaries should survive as long as possible.[7] Priests would pray for its protection in the forthcoming year, and often Psalms 103 and 104 were recited, and the priest would say such sentences as "Cursed is he who transgresseth the bounds or doles of his neighbour".[9] Hymns would be sung, indeed a number of hymns are titled for their role, and many places in the English countryside bear names such as Gospel Oak testifying to their role in the beating of the bounds.

The ceremony had an important practical purpose. Checking the boundaries was a way of preventing encroachment by neighbours; sometimes boundary markers would be moved or lines obscured, and a folk memory of the true extent of the parish was necessary to maintain integrity of borders by embedding knowledge in oral traditions. For a village man dwelling in champion country, or agricultural meadow areas farmed under the traditional open field system, George Homans remarks, "the bounds of his village were the most important bounds he knew."[10] Village and parish were coterminous. The modern system of metes and bounds operates fundamentally similarly, giving a prose definition of a property as if walking about it.

At Manchester in 1597, John Dee recorded in his diary that he with the curate, the clerk and "diverse of the town of diverse ages" perambulated the bounds of the parish taking six days in all.[11] At Turnworth in Dorset the parish register records the perambulation for 1747 thus:[9]

1747. On Ascension Day after morning prayer at Turnworth Church, was made a public Perambulation of the bounds of the parish of Turnworth by me Richd. Cobbe, Vicar, Wm. Northover, Churchwarden, Henry Sillers and Richard Mullen, Overseers and others with 4 boys; beginning at the Church Hatch and cutting a great T on the most principal parts of the bounds. Whipping the boys by way of remembrance, and stopping their cry with some half-pence; we returned to church again, which Perambulation and Processioning had not been made for five years last past.

In a few cases such as the City of Portsmouth the bounds were on the shoreline, and the route was followed by boat rather than on foot.[12]

Origins

In England, the custom dates from Anglo-Saxon times, as it is mentioned in laws of Alfred the Great and Æthelstan. It is thought that it may have been derived from the Roman Terminalia, a festival celebrated on February 22 in honour of Terminus, the god of landmarks, to whom cakes and wine were offered while sports and dancing took place at the boundaries.[7] Similar practices, of pagan origin, were brought by the Norsemen.[13]

In England, a parish ale, a feast, was held after the perambulation, which assured its popularity. In Henry VIII's reign the occasion had become an excuse for so much revelry that it attracted the condemnation of a preacher who declared, "These solemne and accustomable processions and supplications be nowe growen into a right foule and detestable abuse."[7]

Beating the bounds had a religious aspect which is reflected in the rogation, where the accompanying clergy beseech (Latin rogare) the divine blessing upon the parish lands for the ensuing harvest. This feature originated in the 5th century, when Mamertus, Archbishop of Vienne, instituted special prayers, fasting and processions on these days. This clerical side of the parish bounds-beating was one of the religious functions prohibited by the Royal Injunctions of Elizabeth I in 1559; but it was then ordered that the perambulation should continue to be performed as a quasi-secular function, so that evidence of the boundaries of parishes, etc., might be preserved.[14]

Bequests were sometimes made in connection with bounds-beating. For example, at Leighton Buzzard on Rogation Monday, in accordance with the will of Edward Wilkes, a London merchant who died in 1646, the trustees of his almshouses accompanied the boys. The will was read and beer and plum rolls distributed. A remarkable feature of the bequest was that while the will is read one of the boys has to stand on his head.[7]

Observances

England

Although modern surveying techniques make the ceremony obsolete, at least for its secular purpose, many English parishes carry out a regular beating of the bounds, as a way of strengthening the community and giving it a sense of place.[15]

The Tower Liberty, an area surrounding the Tower of London and the neighbouring parish of All Hallows have kept the custom for over seven centuries, both traditions take place on the same day. When the processions of bound-beaters meet, they take part in a mock confrontation commemorating a riot that happened on one occasion in 1698.[16][17]

In 1865–66 William Robert Hicks was mayor of Bodmin in Cornwall, when he revived the custom of beating the bounds of the town. This still takes place more or less every five years and concludes with a game of Cornish hurling. Hurling survives as a traditional part of beating the bounds at Bodmin, commencing at the close of the 'Beat'. The game is organised by the Rotary club of Bodmin and was last played in 2015.[18] The game is started by the mayor of Bodmin by throwing a silver ball into a body of water known as the "Salting Pool". There are no teams and the hurl follows a set route. The aim is to carry the ball from the "Salting Pool" via the old A30, along Callywith Road, then through Castle Street, Church Square and Honey Street to finish at the Turret Clock in Fore Street. The participant carrying the ball when it reaches the turret clock will receive a £10 reward from the mayor.[19][18]

Traditional beating the bounds customs have also taken place in recent times in other parts of Cornwall,[20] Richmond, Yorkshire[3] Barking, London,[21] and Addlestone, Surrey.[22]

In Brightlingsea, Essex, the beating of the bounds is performed in tandem with the "blessing and reclaiming of the waters"; a church service is held at the town's harbour and then the church and civic dignitaries travel the coastal bounds in a sailing vessel where a 'din' is sounded with bells, whistles, shouts and other noise.

After the English Reformation many perambulations became more secular, with the focus on beating the bounds of complete towns or cities, such as Norwich.[23] The Bristol perambulation involved a circuit of the county 'shirestones' each year.

New England

Perambulation of the town borders is a traditional duty of town boards of selectmen in the American states of Massachusetts,[24] New Hampshire,[25] Maine (certain towns),[26] and Connecticut (certain towns).[27] In February 2020, the Portland Press Herald reported that "Maine law used to require neighboring towns to perambulate, or walk their boundaries, every 10 years. In the last century that practice became rare, and in the 1980s, the requirement was taken off the books," according to Robert Yarumian, "a professional land surveyor and owner of Maine Boundary Consultants in Buxton".[28]

Current Vermont statutes make no reference to town boundary perambulation.[29] New Hampshire lawmakers in 2005 and 2015 rejected bills that would have abandoned the requirement that local officials walk their town lines every seven years, though there is no penalty for noncompliance.[30]

State boundaries

The laws of Vermont and New Hampshire require the attorneys general of those states to meet once every seven years to perambulate the boundary between the two states. They do not walk 275 miles (443 km) along the Connecticut River, but they meet at the boundary and formally reaffirm their mutual understanding of the precise location of the boundary. The location had been disputed in the United States Supreme Court in the case of Vermont v. New Hampshire, decided in 1933.[31][32]

The boundary of Connecticut, which meets the states of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and New York, is perambulated every ten years by the Connecticut Department of Transportation.[33][34]

Germany

The town of Biedenkopf, in Hesse, observes a beating of the bounds – called the Grenzgang – every seven years.[35]

See also

- Leyton Marshes (example of an area where the custom has been revived)

- Common Riding (also known as riding the marches; a similar ceremony done on horseback in Scotland)

References

- ↑ "Episode 44: Perambulating the Bounds". Hub History. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ↑ Soth, Amelia (2020-05-07). ""Beating the Bounds"". JSTOR Daily. Retrieved 2021-03-10.

- 1 2 "Mayor wades in as Yorkshire townsfolk stake claim to borders in ancient custom". www.yorkshirepost.co.uk. Retrieved 2021-03-10.

- ↑ "Beating the Bounds – Cholesbury-cum-St Leonards". Retrieved 2021-03-10.

- ↑ George C. Homans, English Villagers of the Thirteenth Century, 2nd ed. 1991:368.

- ↑ The Ordnance Survey of the entire UK only began in the early 19th century and it was many years before the survey was complete.

- 1 2 3 4 5 One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bounds, Beating the". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 324.

- ↑ Tate, W. E.(1946) The Parish Chest. Cambridge: Univ. Press; pp. 73-74

- 1 2 Tate (1946)

- ↑ Homans 1991:368.

- ↑ Frangopulo, N. J. (1962) Rich Inheritance. Manchester: Education Committee; pp. 129-30

- ↑ Gates, William G (1987). Peak, Nigel (ed.). The Portsmouth that has Passed: With a Glimpse of Gosport. Milestone Publications. p. 66. ISBN 1-85265-111-3.

- ↑ Beating the Cholesbury Bounds. Retrieved August 3, 2007.

- ↑ Gibson, Codex juris Ecclesiastici Anglicani (1761) pp. 213-214

- ↑ A Sense of Place - Common Ground website Archived 2008-04-15 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 06 04 2008.

- ↑ Palaces, Historic Royal (2017-05-19). "Beating the Bounds: A centuries-old tradition". HRP Blogs. Retrieved 2021-03-12.

- ↑ by. "Beefeaters Beating the Bounds at the Tower of London". www.ianvisits.co.uk. Retrieved 2022-11-27.

- 1 2 "Bodmin Beating the Bounds & Hurling". Calendar Customs. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- ↑ 2010 Bodmin Hurl Rules Archived 2011-10-05 at the Wayback Machine, Rotary Club of Bodmin, 02/04/2010.

- ↑ Colston, Adrian (2018-08-28). "Beating the Bounds of Gidleigh Common". A Dartmoor blog. Retrieved 2021-03-10.

- ↑ "Boundless Energy: British Pathé Go Beating The Bounds – British Pathé and the Reuters historical collection". www.britishpathe.com. Retrieved 2021-03-10.

- ↑ Pathé, British. "Beating The Bounds At Addlestone". www.britishpathe.com. Retrieved 2021-03-10.

- ↑ L. Matthew Woodcock, ‘Perambulation and Performance in Early Modern Festive Culture’, Early Theatre: A Journal associated with the Records of Early English Drama, 23(2), (2020), 144-47

- ↑ Mass. Gen. L. c. 42, § 2

- ↑ TITLE III TOWNS, CITIES, VILLAGE DISTRICTS, AND UNINCORPORATED PLACES CHAPTER 51 TOWN LINES AND PERAMBULATION OF BOUNDARIES Section 51:2 . Retrieved March 7, 2008.

- ↑ "§2851. Identification of boundary lines". Maine Revised Statutes. Maine Legislature. 5 December 2019. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ↑ Dee, Jane (23 April 1998). "A Grand Tradition: Perambulating the Bounds". Hartford Courant. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ↑ Graham, Gillian (3 February 2020). "Border dispute between Maine's 2 oldest towns goes back 368 years". Portland Press Herald. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ↑ "Chapter 47: Municipal Lines". The Vermont Statutes Online. State of Vermont. 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ↑ Leubsdorf, Ben (May 23, 2015). "Some Devoted New Englanders Went for a Stroll in 1651 and Haven't Stopped Since". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- ↑ Vermont Statutes, Title 1: Chapter 15: New Hampshire–Vermont Boundary

- ↑ "Attorneys General Delaney and Sorrell Will Meet on the Norwich/Hanover Bridge on May 14th for the Eleventh Perambulation of the NH/VT Boundary". New Hampshire Department of Justice, Office of the Attorney General. May 10, 2012. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- ↑ "State Line Perambulation". Connecticut Department of Transportation. State of Connecticut. 25 April 2012. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ↑ Leff, David (7 October 2007). "The Thin State Line: Boundary With R.I. Vanishing". Hartford Courant. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ↑ "Grenzgang in Biedenkopf". biedenkopf.de. Archived from the original on 2013-09-26.

Further reading

Berwick, David A. Beating the Bounds in Georgian Norwich. Larks Press (www.booksatlarkspress.co.uk), Ordnance Farmhouse, Guist Bottom, Dereham, Norfolk, UK: 2007. ISBN 978-1-904006-35-0