Beatty | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname: Gateway to Death Valley[1] | |

Location of Beatty, Nevada | |

| Coordinates: 36°54′34″N 116°45′16″W / 36.90944°N 116.75444°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | |

| Founded | 1905 |

| Named for | "Old Man" Montillus (Montillion) Murray Beatty |

| Area | |

| • Total | 17.70 sq mi (45.85 km2) |

| • Land | 17.68 sq mi (45.80 km2) |

| • Water | 0.02 sq mi (0.06 km2) |

| Elevation | 3,307 ft (1,008 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 880 |

| • Density | 49.77/sq mi (19.22/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP code | 89003 |

| Area code | 775 |

| FIPS code | 32-05100 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0845356 |

| Website | Beatty, Nevada |

| Official name | Beatty (Center of the Gold Railroads--"Chicago of the West") |

| Reference no. | 173 |

Beatty (/ˈbeɪti/ BAYT-ee) is an unincorporated town[3] along the Amargosa River in Nye County, Nevada, United States. U.S. Route 95 runs through the town, which lies between Tonopah, about 90 miles (140 km) to the north and Las Vegas, about 120 miles (190 km) to the southeast. State Route 374 connects Beatty to Death Valley National Park, about 8 miles (13 km) to the west.

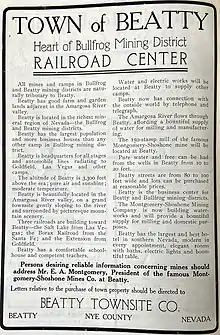

Before the arrival of non-indigenous people in the 19th century, the region was home to groups of Western Shoshone. Established in 1905, the community was named after Montillus (Montillion) Murray "Old Man" Beatty, who settled on a ranch in the Oasis Valley in 1896 and became Beatty's first postmaster. With the arrival of the Las Vegas and Tonopah Railroad in 1905, the town became a railway center for the Bullfrog Mining District, including mining towns such as nearby Rhyolite.[4] Starting in the 1940s, Nellis Air Force Base and other federal installations contributed to the town's economy as did tourism related to Death Valley National Park and the rise of Las Vegas as an entertainment center.

Beatty is home to the Beatty Museum and Historical Society and to businesses catering to tourist travel. The ghost town of Rhyolite and the Goldwell Open Air Museum (a sculpture park), are both about 4 miles (6 km) to the west, and Yucca Mountain and the Nevada Test Site are about 18 miles (29 km) to the east.

History

Before the arrival of non-indigenous explorers, prospectors, and settlers, Western Shoshone in the Beatty area hunted game and gathered wild plants in the region. It is estimated that the 19th-century population density of the Indians near Beatty was one person per 44 square miles (110 km2). By the middle of the century, European diseases had greatly reduced the Indian population, and incursions by newcomers had disrupted the native traditions. In about 1875, the Shoshone had six camps, with a total population of 29, along the Amargosa River near Beatty. Some of the survivors and their descendants continued to live in or near Beatty, while others moved to reservations at Walker Lake, Reese River, Duckwater, or elsewhere.[5]

Beatty is named after "Old Man" Montillus (Montillion) Murray Beatty, a Civil War veteran and miner who bought a ranch along the Amargosa River just north of the future community[6] and became its first postmaster in 1905.[7] The community was laid out in 1904 or 1905 after Ernest Alexander "Bob" Montgomery, owner of the Montgomery Shoshone Mine near Rhyolite, decided to build the Montgomery Hotel in Beatty.[8] Montgomery was drawn to the area, known as the Bullfrog Mining District, because of a gold rush that began in 1904 in the Bullfrog Hills west of Beatty.[9]

During Beatty's first year, wagons pulled by teams of horses or mules hauled freight between the Bullfrog district (that included the towns of Rhyolite, Bullfrog, Gold Center, Transvaal, and Springdale) and the nearest railroad, in Las Vegas, and by the middle of 1905, about 1,500 horses were engaged in this business.[10] In October 1906, the Las Vegas and Tonopah Railroad (LV&T) began regular service to Beatty; in April 1907, the Bullfrog Goldfield Railroad (BG) reached the community, and the Tonopah and Tidewater (T&T) line added a third railroad in October 1907.[4] The LV&T ceased operations in 1918, the BG in 1928, and the T&T in 1940.[4] Until the railroads abandoned their lines, Beatty served as the railhead for many mines in the area, including a fluorspar mine on Bare Mountain, to the east.[11]

Beatty's first newspaper was the Beatty Bullfrog Miner, which began publishing in 1905 and went out of business in 1909. The Rhyolite Herald was the region's most important paper, starting in 1905 and reaching a circulation of 10,000 by 1909. It ceased publication in 1912, and the Beatty area had no newspaper from then until 1947. The Beatty Bulletin, a supplement to the Goldfield News, was published from then through 1956.[12]

Beatty's population grew slowly in the first half of the 20th century, rising from 169 in 1929 to 485 in 1950.[13] The first reliable electric company in the community, Amargosa Power Company, began supplying electricity in about 1940. Phone service arrived during World War II, and the town installed a community-wide sewer system in the 1970s.[14] When a new mine opened west of Beatty in 1988, the population briefly surged from about 1,000 to between 1,500 and 2,000 by the end of 1990.[15] Since the mine's closing in 1998, the population has fallen again to near its former level.

Geography and climate

Beatty lies along U.S. Route 95 between Tonopah, about 90 miles (140 km) to the north, and Las Vegas, about 120 miles (190 km) to the southeast. State Route 374 connects Beatty to Death Valley National Park, about 8 miles (13 km) to the west. Yucca Mountain and the Nevada Test Site are about 18 miles (29 km) to the east.[16] The most densely populated part of the census-designated place (CDP) of Beatty is at 36°54′34″N 116°45′16″W / 36.90944°N 116.75444°W (36.909337, −116.754531),[17] although the CDP extends well beyond this urban center.[18][19] According to the United States Census Bureau, the CDP has a total area of 175.6 square miles (455 km2), all land.[20] The most populated area lies at 3,307 feet (1,008 m) above sea level[21] between Beatty Mountain and Bare Mountain to the east and the Bullfrog Hills to the west. The Amargosa River, an intermittent river that ends in Death Valley, flows on the surface through part of the CDP but has not been counted as water in the Census Bureau statistics.

Nevada's main climatic features are bright sunshine, low annual precipitation, heavy snowfall in the higher mountains, clean, dry air, and large daily temperature ranges. Strong surface heating occurs by day and rapid cooling by night, and usually even the hottest days have cool nights. The average percentage of possible sunshine in southern Nevada is more than 80 percent. Sunshine and low humidity in this region account for an average evaporation, as measured in evaporation pans, of more than 100 inches (2,500 mm) of water a year.[22]

Beatty receives only 5.71 inches (145 mm) of precipitation a year.[23] Precipitation of at least .01 inches (0.25 mm) falls on an average of 21 days annually.[24] The wettest year was 1941 with 11.89 in (302 mm) and driest year was 1953 with 0.69 in (18 mm).[24] The monthly daily average temperature ranges from 41.1 °F (5.1 °C) in December to 80.2 °F (26.8 °C) in July. On average, there are 26 days of 100 °F (38 °C)+ highs, 97 days of 90 °F (32 °C)+, and 38 days where the high remains at or below 50 °F (10 °C); the average window for freezing temperatures is November 2 to April 6. Snow is uncommon and measurable (≥0.1 in or 0.25 cm) amounts occur in less than 60 of seasons. The highest recorded temperature was 115 °F (46 °C) on June 11, 1961,[25] and the lowest was 1 °F (−17 °C) on February 2, 1933.[25]

| Climate data for Beatty, Nevada (1991–2020 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 56.5 (13.6) |

60.0 (15.6) |

67.5 (19.7) |

73.4 (23.0) |

83.3 (28.5) |

93.5 (34.2) |

99.4 (37.4) |

98.4 (36.9) |

91.0 (32.8) |

78.9 (26.1) |

65.8 (18.8) |

56.1 (13.4) |

77.0 (25.0) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 41.9 (5.5) |

45.2 (7.3) |

51.1 (10.6) |

56.5 (13.6) |

65.7 (18.7) |

74.2 (23.4) |

80.8 (27.1) |

79.0 (26.1) |

71.7 (22.1) |

61.4 (16.3) |

49.2 (9.6) |

41.2 (5.1) |

59.8 (15.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 27.4 (−2.6) |

30.4 (−0.9) |

34.7 (1.5) |

39.7 (4.3) |

48.1 (8.9) |

55.0 (12.8) |

62.3 (16.8) |

59.5 (15.3) |

52.3 (11.3) |

44.0 (6.7) |

32.6 (0.3) |

26.2 (−3.2) |

42.7 (5.9) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.79 (20) |

1.00 (25) |

0.96 (24) |

0.38 (9.7) |

0.31 (7.9) |

0.17 (4.3) |

0.60 (15) |

0.30 (7.6) |

0.36 (9.1) |

0.23 (5.8) |

0.30 (7.6) |

0.86 (22) |

6.26 (159) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 1.0 (2.5) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0.7 (1.8) |

2.6 (6.6) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 3.5 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 28.7 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 1.3 |

| Source: NOAA[23] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 880 | — | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[26] | |||

As of the census of 2000, there were 1,154 people, 535 households, and 270 families residing in the CDP. The population density was 6.6 inhabitants per square mile (2.5/km2). There were 740 housing units at an average density of 4.2 per square mile (1.6/km2). The racial makeup of the CDP was 90.9% White, 0.1% African American, 1.5% Native American, 1.2% Asian, 3.1% from other races, and 3.2% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 8.9% of the population. There were 535 households, out of which 26.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 39.8% were married couples living together, 6.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 49.5% were non-families. 43.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 15.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.16 and the average family size was 3.04. In the CDP the population was spread out, with 26.1% under the age of 18, 5.6% from 18 to 24, 24.7% from 25 to 44, 29.5% from 45 to 64, and 14.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 40 years. For every 100 females, there were 119.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 121.6 males. The median income for a household in the CDP was $41,250, and the median income for a family was $52,639. Males had a median income of $44,438 versus $25,962 for females. The per capita income for the CDP was $16,971. About 10.4% of families and 13.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 7.1% of those under age 18 and 19.6% of those age 65 or over. As of the 2010 census, 1,010 people lived in Beatty.[27]

Government

Under the terms of the Unincorporated Town Government Law of Nevada, Beatty is governed by the Nye County Commission assisted by a local board acting as a liaison between the citizens of Beatty and the commissioners.[28] The Beatty Town Advisory Board consists of five elected members who meet twice a month at the Beatty Community Center.[29] The Beatty General Improvement District manages the community's parks, swimming pool, putting course, and other recreational grounds.[30]

Lorinda Wichman, John Koenig, Donna Cox, Leo Blundo, and Debra Strickland are the county commissioners in 2021.[31] Among the many county departments are administration, works and roads, building and code compliance, sheriff, animal control, planning, property assessment, the Fifth Judicial District Court, health and human services, senior centers including the Beatty Senior Center, and lower courts including the Beatty Justice Court.[32] The Nye County Sheriff's Office has a substation in Beatty.[33] Among other things, the office handles dispatch for the Beatty Volunteer Fire Department, which provides firefighting and ambulance services.[34]

Gregory Hafen II, a Republican, represents Beatty and the rest of District 36 in the Nevada Assembly.[35] In the Nevada Senate, Beatty, as part of District 19, is represented by Pete Goicoechea, a Republican.[35]

Mark Amodei, a Republican, represents Beatty and the rest of Nevada's Second Congressional District in the United States House of Representatives. Jacky Rosen and Catherine Cortez Masto, both Democrats, represent Nevada in the United States Senate.[36]

Economy

%252C_Main_Street.jpg.webp)

Early businesses in Beatty included the Montgomery Hotel, built by a mine owner in 1905,[8] and freight businesses first centered on horse-drawn wagons and later on railroads serving the mining towns in the Bullfrog district.[37] Beatty became the economic center for a large sparsely populated region. Aside from mining, other activities sustaining the community during the 1920s and 1930s included retail sales, gas and oil distribution, construction of Scotty's Castle, and the production and sale of illegal alcohol during Prohibition.[38]

Nevada's legalization of gambling in 1931, the establishment of Death Valley National Monument in 1933, and the rise of Las Vegas as an entertainment center, brought visitors to Beatty, which became increasingly tourist-oriented.[39]

As underground mining declined in the region, federal defense spending, starting with the Nellis Air Force Range in 1940 and the Nevada Test Site in 1950, also contributed to the local economy.[39] However, in 1988, an open-pit mine and mill began operations about 4 miles (6.4 km) west of Beatty along State Route 374. Barrick Gold acquired the mine in 1994 and continued to extract and process ore at what became known as the Barrick Bullfrog Mine.[40] At its peak, the mine employed 540 workers, many of whom lived in Beatty.[15] The mine closed in 1998.[40]

In 2004, the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) named the closed Barrick Bullfrog mine site as one of six slated for pilot reclamation projects under the national Brownfields Mine-Scarred Land Initiative. A local group, the Beatty Economic Development Corporation (BEDC), in discussions with the EPA, suggested solar-power generation as a potential use for the site.[41] Barrick Gold later transferred 81 acres (33 ha) of its land to Beatty.[42] In February 2009, the New York Times published a Greenwire article suggesting that part of the economic stimulus money from the $787 billion American Recovery and Reinvestment Act might finance the Beatty project. "Studies show that the Beatty area has some of the best solar energy potential in the United States, as well as a high potential for wind-power generation," the Greenwire story said.[42]

The Beatty Chamber of Commerce web site describes the community as the Gateway to Death Valley, a small rural locality that has "everything the desert visitor needs" including motels and recreational vehicle (RV) sites.[43] Aside from tourism, businesses contributing to the local economy include mining, retail trade, public administration and gambling.[44]

Burro races

From 1961 until 1972 the local Lions Club held annual burro races that drew competitors from the United States, Canada, and as far away as Iran. National attention was brought to the race when Reg Potterton wrote a feature article about the 1971 race for Playboy magazine. The story, appearing in the May 1972 issue, featured stories about the town, the contestants, and the tourists who attended.[45] Eventually the races were discontinued after organizers decided that the visitors they attracted were not good for Beatty's image.[46]

Infrastructure and culture

The community is home to the Beatty Museum and Historical Society. The ghost town of Rhyolite and the Goldwell Open Air Museum, a sculpture park, are about 4 miles (6 km) to the west. Bailey's Hot Springs and bathhouses are about 5 miles (8 km) north of Beatty in the Oasis Valley. In addition to highways, Beatty has a general aviation airfield, Beatty Airport, about 3 miles (5 km) south of downtown. Beatty Medical Center, which opened in 1977, provides family medicine and other services.[47] The Beatty Library is the only library in Nevada that is housed in a geodesic dome.[48] Beatty's combined elementary and middle schools, serving kindergarten through eighth grade, and Beatty High School, grades 9–12, are part of the Nye County School District.[49] The Beatty Water and Sanitation District supplies drinking water from three wells to the town residents and treats the community's wastewater.[50]

References

- ↑ Waite, Mark (November 7, 2007). "Death Valley may choose Hafen Commercial Center for offices". Pahrump Valley Times. Archived from the original on November 8, 2007. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- ↑ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 19, 2022.

- ↑ "2014 Estimates". Nevada State Demographer's Office. Archived from the original on July 7, 2017. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- 1 2 3 McCracken, History, pp. 56–59

- ↑ McCracken, History, pp. 8–12

- ↑ McCracken, History, pp. 21–22

- ↑ McCracken, History, p. 6

- 1 2 McCracken, History, pp. 48–49

- ↑ Lingenfelter, p. 203

- ↑ McCracken, History, p. 52

- ↑ McCracken, History, pp. 62–70

- ↑ McCracken, History, pp. 49–51

- ↑ McCracken, History, pp. 102–03

- ↑ McCracken, History, pp. 92–93

- 1 2 McCracken, History, pp. 155–57

- ↑ The Road Atlas (Map) (2008 ed.). Rand McNally & Company. § 64. ISBN 0-528-93961-0.

- ↑ "U.S. Gazetteer files: 2000 and 1990". May 3, 2005. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ↑ "2010 Boundary and Annexation Survey (BAS): Nye County, NV" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 9, 2011. Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- ↑ "2010 Boundary and Annexation Survey (BAS): Nye County, NV (inset map of population center)" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 9, 2011. Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- ↑ "United States Gazetteer files: 2000 and 1990 (places)". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on October 21, 2002. Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- ↑ "Beatty". Geographic Names Information System (GNIS). United States Geological Survey. December 12, 1980. Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- ↑ Nevada state climatologists. "Climate of Nevada". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on May 26, 2017. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- 1 2 "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 19, 2013.

- 1 2 "Period of Record General Climate Summary - Precipitation". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- 1 2 "Beatty, Nevada: Period of Record General Climate Summary - Temperature". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ↑ "American FactFinder: Beatty CDP, Nevada". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved August 25, 2012.

- ↑ "State and Local Government: Nevada Legislative Counsel Bureau Research Division Policy Brief" (PDF). The Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund. January 2005. p. 244. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 7, 2006. Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- ↑ "Beatty Town Advisory Board". The Town of Beatty. 2009. Retrieved July 28, 2012.

- ↑ "BGID – Parks and Recreation". The Town of Beatty. 2009. Archived from the original on October 17, 2010. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- ↑ "Board of County Commissioners". Nye County, Nevada. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- ↑ "Staff Directory: Categories". Nye County, Nevada. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- ↑ "Nye County Sheriff – Beatty Sub Station". The Town of Beatty. 2009. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- ↑ "Beatty Volunteer Fire Department". The Town of Beatty. 2009. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- 1 2 "Legislative Districts 2019" (PDF). Nevada Legislature. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- ↑ "Nevada". GovTrack. Civic Impulse. Retrieved May 10, 2017.

- ↑ McCracken, History, pp. 52–59

- ↑ McCracken, History, p. 74

- 1 2 McCracken, History, pp. 101–02

- 1 2 Kump, Dan; Arnold, Tim. "Underhand Cut-and-Fill at the Barrick Bullfrog Mine". In Hustrulid, William A.; Bullock, Richard L. (eds.). Underground Mining Methods. Littleton, Colo.: Society for Mining, Metallurgy, and Exploration. pp. 345–50. ISBN 978-0-87335-193-5.

- ↑ "U.S. EPA Selects Former Nye County Gold Mine for National Brownfields Pilot". United States Environmental Protection Agency. May 18, 2004. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- 1 2 Streater, Scott (February 26, 2009). "Polluted Mines as Economic Engines? Obama Admin Says 'Yes'". New York Times. E&E Publishing. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Beatty, Nevada: Where Adventure Awaits You". Beatty Chamber of Commerce. 2007. Archived from the original on 22 May 2010. Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- ↑ "Beatty Community Profile". Beatty Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on 22 May 2010. Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- ↑ Potterton, Reg (May 1972). "The Great Race". Playboy: 111–12, 186–88.

- ↑ "Beatty, Nevada, History". Beatty Museum and Historical Society. 2010. Archived from the original on March 2, 2010. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- ↑ "Beatty Medical Center Nevada". Nevada Health Centers, Inc. 2008. Archived from the original on 11 February 2009. Retrieved March 14, 2009.

- ↑ "About". Beatty Library District. 2018. Retrieved September 20, 2018.

- ↑ Staff writer. "Nye County School District School". Nye County School District. Archived from the original on July 20, 2012. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- ↑ Farr West Engineering (November 2008). "Beatty Water and Sanitation District: Water Conservation Plan" (PDF). The Town of Beatty. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 21, 2011. Retrieved June 5, 2010.