The narrative of Bel and the Dragon is incorporated as chapter 14 of the extended Book of Daniel. The original Septuagint text in Greek survives in a single manuscript, Codex Chisianus, while the standard text is due to Theodotion, the 2nd-century AD revisor.

This chapter, along with chapter 13, is considered deuterocanonical: it was unknown to early Rabbinic Judaism, and while it is considered non-canonical by most Protestants, it is canonical to Eastern Orthodox Christians, and is found in the Apocrypha section of some Protestant Bibles.[1]

Summaries

The chapter contains a single story which may previously have represented three separate narratives,[2][3][4] which place Daniel at the court of Cyrus, king of the Persians: "When King Astyages was laid to rest with his ancestors, Cyrus the Persian succeeded to his kingdom."[5][6] There Daniel "was a companion of the king, and was the most honored of all his Friends".[7]

Bel

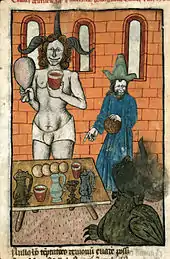

The narrative of Bel (Daniel 14:1–22) ridicules the worship of idols. The king asks Daniel, "You do not think Bel is a living god? Do you not see how much he eats and drinks every day?"[8] to which Daniel answers that the idol is made of clay covered by bronze and thus cannot eat or drink. Enraged, the king then demands that the seventy priests of Bel show him who consumes the offerings made to the idol. The priests then challenge the king to set the offerings as usual (which were "twelve great measures of fine flour, and forty sheep, and six vessels of wine") and then seal the entrance to the temple with his ring: if Bel does not consume the offerings, the priests are to be sentenced to death; otherwise, Daniel is to be killed.

Daniel then uncovers the ruse (by scattering ashes over the floor of the temple in the presence of the king after the priests have left) and shows that the "sacred" meal of Bel is actually consumed at night by the priests and their wives and children, who enter through a secret door when the temple's doors are sealed.

The next morning, the king comes to inspect the test by observing from above. He sees that the food has been consumed and points out that the wax seals he put on the temple doors are unbroken, and offers a hosanna to Bel. Daniel calls attention to the footprints on the temple floor; which the king then realizes by seeing footprints, along with more slender ones and smaller ones, shows that women and children also participated in the gluttony. The priests of Bel are then arrested and, confessing their deed, reveal the secret passage that they used to sneak inside the temple. They, their wives and children are put to death, and Daniel is permitted to destroy the idol of Bel and the temple. This version has been cited as an ancestor of the "locked-room mystery".[9]

The dragon

In the brief but autonomous companion narrative of the dragon (Daniel 14:23–30).... , "There was a great dragon which the Babylonians revered."[10] Some time after the temple's condemnation the Babylonians worship the dragon (presumably a snake[11] or lizard) . The king says that unlike Bel, the dragon is a clear example of a live animal. Daniel promises to slay the dragon without the aid of a sword, and does so by baking pitch, fat, and hair (trichas) to make cakes (mazas, barley-cakes) that cause the dragon to burst open upon consumption. In other variants, other ingredients serve the purpose: in a form known to the Midrash, straw was fed in which nails were hidden,[12] or skins of camels were filled with hot coals.[13] A similar story occurs in the Persian poet Ferdowsi's Shahnameh, where Alexander the Great, or "Iskandar", kills a dragon by feeding it cow hides stuffed with poison and tar.[14][15]

Earlier scholarship has suggested a parallel between this text and the contest between Marduk and Tiamat in Mesopotamian mythology, where the winds controlled by Marduk burst Tiamat open[16] and barley-cake plays the same role as the wind.[17] However, David DeSilva (2018) casts doubt on this reading.[18]

See also

References

- ↑ Apocrypha-KJV-Reader's. Hendrickson Publishers. 2009. ISBN 978-1-59856-464-8.

- ↑ The Jerome Biblical Commentary, vol. 1, p. 460, says of the second episode, "Although once an independent story, in its present form it is edited to follow the preceding tale;"

- ↑ Daniel J. Harrington writes of Daniel 14:23–42: "This addition is a combination of three episodes" (Harrington, Invitation to the Apocrypha, p. 118);

- ↑ Robert Doran writes, "The links between all the episodes in both versions are so pervasive that the narrative must be seen to be a whole. Such stories, of course, could theoretically have existed independently, but there is no evidence that they did." (Harper's Bible Commentary, p. 868).

- ↑ Daniel 14:1, but Daniel 13:66 in the Vulgate

- ↑ In the Greek version that has survived, the verb form parelaben is a diagnostic Aramaism, reflecting Aramaic qabbel which here does not mean "receive" but "succeed to the Throne" (F. Zimmermann, "Bel and the Dragon", Vetus Testamentum 8.4 (October 1958), p 440.

- ↑ Daniel 14:2, but Daniel 14:1 in the Vulgate

- ↑ Daniel 14:6, New American Bible

- ↑ Westlake, Donald E. (1998). "The Locked Room". Murderous Schemes: An Anthology of Classic Detective Stories. Oxford University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-19-510487-5.

- ↑ New American Bible, verse 23

- ↑ maybe an indian python, one of the longest snakes in the world.

- ↑ Zimmermann 1958:438f, note 1 compares A. Neubauer, Book of Tobit (Oxford) 1878:43.

- ↑ Zimmermann 1958:439, note 2 attests the Talmudic tractate Nedarim, ed. Krotoschin, (1866) 37d.

- ↑ Zimmermann 1958:439, note 3 attests Spiegel, Iranische Altertümer II.293 and Theodor Nöldeke, Beiträge zur geschichte Alexanderromans (Vienna) 1890:22.

- ↑ "Alexander the Great in Firdawsi's Book of Kings".

- ↑ "Bel and the Dragon". Jewish Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. 1900s. pp. 650–1. Retrieved 6 August 2015.; Zimmermann 1958.

- ↑ Zimmermann 1958:440.

- ↑ DeSilva, David. Introducing the Apocrypha, 2nd Edition Message, Context, and Significance. Baker Academic, 2018, 250–263.

Sources

- Levine, Amy-Jill 2010. "Commentary on 'Bel and the Dragon'" in Coogan, Michael D. The New Oxford Annotated Bible (fourth ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

- F. Zimmermann, "Bel and the Dragon", Vetus Testamentum 8.4 (October 1958)

External links

Works related to Bible (King James)/Bel and the Dragon at Wikisource

Works related to Bible (King James)/Bel and the Dragon at Wikisource Media related to History of Bel and the Dragon at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to History of Bel and the Dragon at Wikimedia Commons