| Bentworth | |

|---|---|

| Village | |

Clockwise from top: St Mary's Church, Thedden Grange, farmland near Childer Hill, Bentworth village centre (with the Star Inn and gold postbox), the Sun Inn, and Hall Place | |

Bentworth Location within Hampshire | |

| Population | 553 (2011 Census)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SU664401 |

| • London | 44 mi (71 km) ENE |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Alton |

| Postcode district | GU34 |

| Dialling code | 01420 |

| Police | Hampshire and Isle of Wight |

| Fire | Hampshire and Isle of Wight |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | bentworth |

Bentworth is a village and civil parish in the East Hampshire district of Hampshire, England. The nearest town is Alton, which lies about 3 miles (5 km) east of the village. It sits within the East Hampshire Hangers, an area of rolling valleys and high downland. The parish covers an area of 3,763 acres (15.23 km2) and at its highest point is the prominent King's Hill, 716 feet (218 m) above sea level. According to the 2011 census, Bentworth had a population of 553.[1]

The village has a long history, as shown by the number and range of its heritage-listed buildings. Bronze Age and Roman remains have been found in the area and there is evidence of an Anglo-Saxon church in the village. The manor of Bentworth was not named in the Domesday Book of 1086, but it was part of the Odiham Hundred. Land ownership of the village was passed by several English kings until the late Elizabethan era. During the Second World War, Bentworth Hall was requisitioned as an outstation for the Royal Navy and nearby Thedden Grange was used as a prisoner of war camp. Parts of the village were designated a conservation area in 1982.

The parish contains several manors including Bentworth Hall, Hall Place, Burkham House, Wivelrod Manor, Gaston Grange and Thedden Grange. The 500-acre (2.0 km2) estate of Bentworth Hall was split up as a result of various sales from the 1950s. St Mary's Church, a Grade II* listed building which parts of which date back to the late 11th century, lies at the centre of the village. The village has two public houses, the Star Inn and the Sun Inn;[lower-alpha 1] a primary school; and its own cricket club. Bentworth formerly had a railway station, Bentworth and Lasham, on the Basingstoke and Alton Light Railway until the line's closure in 1936. The nearest railway station is now 3.8 miles (6.1 km) east of the village, at Alton.

History

Prehistory to Roman

The village name has been spelt in different ways, including: Bentewurda or Bintewurda (12th century) and Bynteworth (c. 15th century).[3][4] The original meaning of the name Bent-worth may have been a place of cultivated land, or a way through land such as woodland.[5] The Swedish scholar Eilert Ekwall argues that a derivation from the Old English bent-grass is unlikely, and suggests a derivation from The tũn of Bynna's people.[6]

In October 1935 a Neolithic basalt axe-head was found in the village, indicating occupation in prehistoric times.[7] Pot sherds and faunal remains from the Iron Age and several coins have been discovered, including a Bronze coin from the rein of Valentinian I,[8] discovered in 1956.[7] The Romans built a road between the Roman town of Silchester to the north of Old Basing, and the Roman settlement of Vindomis, just east of the present-day town of Alton, which measured 15 Roman miles.[9][10]

A Bronze Age cremation urn was found in 1955 just north of Nancole Copse, approximately 2.5 miles (4.0 km) from St Mary's Church.[8] The urn is now displayed in the Curtis Museum in Alton. Belgic pottery and animal bones were found in 1954 at Holt End, a hamlet south of Bentworth. Pottery, bone objects, spindle-whorls (stone discs with a hole in the middle used in spinning thread) and fragments of Roman roofing tiles were unearthed at Wivelrod Manor.[8]

Medieval

Bentworth was not mentioned separately in the 1086 Domesday Survey, although the entry for the surrounding Hundred of Odiham mentions that it had a number of outlying parishes that included Bentworth.[11] Soon after Domesday, Bentworth became an independent manor. Between 1111 and 1116 it was granted by Henry I to Geoffrey, Count of Anjou.[11]

The earliest mention of Bentworth village was in the charter of 1111–1116 from Henry I to the Archdiocese of Rouen of "the manor of Bynteworda and the berewica (outlying farm) of Bercham (present day Burkham)".[12] St Mary's Church was not included in this charter but in 1165 King Henry II granted it to Roturn, then the Archdiocese of Rouen.[12] When King John began losing his possessions in Normandy he took back the ownership of several manors, including Bentworth. He then ceded Bentworth manor to Peter des Roches, the Bishop of Winchester, in 1207–8.[13] The manor was returned to Rouen, who held the property until 1316, when Edward II appointed Peter de Galicien as its custodian.[4]

Some time after 1280 a new stone hall house was built at Bentworth, a typical medieval hall house and has been variously called Bentworth Hall (until 1832) and Bentworth Manor House. Since 1832 it has been known as Hall Place. In 1333 the property owner was granted the right for a private chapel on the premises.[12] Maud de Aula was given permission to hold services at Bentworth Hall chapel from 1333 to 1345;[14] the remains of this building can be seen today immediately to the southwest of Hall Place. In February 1336 to manor was granted to Peter, Archbishop of Rouen, but he appeared to subsequently have nothing to do with it, as four months later ownership of the manor passed to William Melton, the Archbishop of York. Upon his death in 1340 he left his possessions to his nephew William de Melton, the son of his brother Henry.[4]

In 1348, William de Melton obtained King Edward III's permission to give his manor to William Edendon, Bishop of Winchester. The ownership of the manor of Bentworth was then passed by marriage to the Windsor family, who had been constables of Windsor Castle. The Bentworth Hall estate was evidently returned to the Melton family, because it is mentioned among their possessions in a document dated to 1362. It then passed to William's similar-named son, Sir William de Melton.[4] Sir William's son, John de Melton, who inherited the house in 1399, was recorded as owner of the manor of Bentworth in 1431. He died in 1455, and was succeeded by his son until the latter's death in 1474, then finally his grandson John Melton. After the death of the last, the manor of Bentworth remained in the possession of the Windsor family for at least 150 years.[15]

Elizabethan to Georgian

The Windsors owned many manors, including Bentworth. An example is from the will of Edward, 3rd Lord Windsor, dated 20 December 1572 which contains the words: " ... touching the disposition of ... all those my manors of Bentworth Hall, Burkham, Astleye, Mill Court and Thrustons ... in the county of Southampton ... "

Twelve years later in 1590, the 5th Lord Windsor, Henry Windsor (1562–1605), sold the manor of Bentworth to the Hunt family, who had been tenants since the beginning of the 1500s.

Ownership passed in 1610 to Sir James Woolveridge of Odiham and in 1651 to Thomas Turgis, a wealthy London merchant. His son, also Thomas, described as one of the richest commoners in England, left the manor of Bentworth to his relative William Urry, of Sheat Manor in 1705.[4]

In 1777 William Urry's daughters Mary and Elizabeth married two brothers, Basil and William Fitzherbert of Swynnerton Hall, Staffordshire.[4] Their sister-in-law was Maria Fitzherbert,[16] the secret wife of the Prince Regent, later King George IV. In about 1800, Mary Fitzherbert (who had eleven children) became owner of Bentworth Manor and Manor Farm.[4]

19th century to the Second World War

In 1832 the Fitzherbert family sold the Bentworth Hall estate at an auction in London to Roger Staples Horman Fisher for approximately £6000. Almost immediately Fisher started building the present Bentworth Hall.[17] In 1848 the estate was sold to Jeremiah Robert Ives.[18] The Ives family later shared ownership with the author George Cecil Ives who lived for a time at the hall with his paternal grandmother.[19] In 1898 a station for the Basingstoke and Alton Light Railway was proposed which would serve Bentworh, Lasham and the village of Shalden. Land was taken from the villages of Bentworth and Lasham to provide for the railway station.[20] In 1870–72 the Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales by John Marius Wilson described Bentworth as

... a village and parish in Alton district, Hants. The village stands 3½ miles WNW of Alton r. station, and had a post office under Alton. The parish comprises 3,688 acres (1,492 ha). Real property, £4,091. Pop., 647. Houses, 123. George Withers, the poet; sold property in Bentworth at the outbreak of the civil war (1642), to raise a troop of horse. The living is a rectory in the diocese of Winchester. Value, £760, Patron, the Rev. Mr. Mathews. There is a dissenting Chapel.[21]

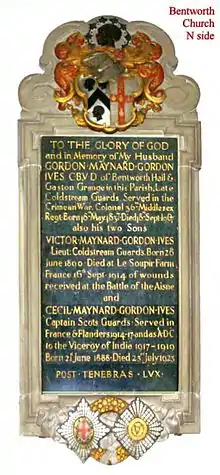

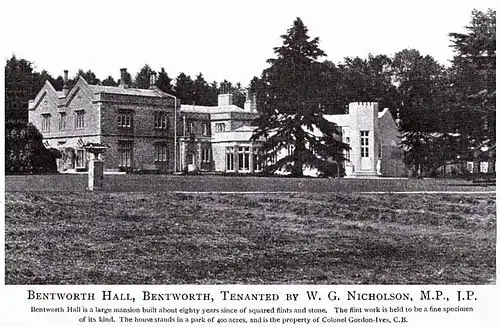

In 1897 Emma Ives died and ownership of the Bentworth Hall estate passed to her son Colonel Gordon Maynard Gordon-Ives, who had in 1870 had built Gaston Grange as his residence. After his mother died he continued to live there, leasing Bentworth Hall to William Nicholson, the Member of Parliament for Petersfield.[22] Gordon-Ives died on 8 September 1907 and the estate passed to his son, Cecil Maynard Gordon-Ives, a Captain of the Scots Guards in the First World War, who occupied it until his death on 23 July 1923.[22][23][lower-alpha 2] The Bentworth Hall Estate was then purchased by Arthur d'Anyers Willis in 1924 and was sold again to Major John Arthur Pryor in 1932, who lived at Bentworth Hall until the estate was taken over by the military during the Second World War.[22]

Second World War

Bentworth Hall was requisitioned for war use and was where a number of organisations were based. In 1941 it was used by the Mobile Naval Base Defence Organization (MNBDO) and it was later an outstation of the Royal Navy's Haslar Hospital in Portsmouth, the bedrooms being used as wards. Later, it was occupied by officers from the airfield at Lasham; one commander kept an aircraft in a field towards New Copse and used it as transport to Lasham Airfield. From 1942 to 1944 Thedden Grange was used as a prisoner of war camp.[24][25] During the war nissen huts were built on what is now the Complins housing estate. The War Department had occupied the Holybourne property and constructed 26 nissen huts and other structures on the grounds, some of which were converted into civilian housing after the war. In 1966 the property was sold and 41 homes were built on the former site of Complins estate and brewery.[26]

Post-war

In 1947 the Bentworth Hall estate was bought by Major Herbert Cecil Benyon Berens, who was a director of Hambros Bank in London from 1968.[22][27] In 1950 Berens built two new lodge houses at the junction of the drive to Bentworth Hall towards the main road through the village.[22] Their family arms included a bear, and when Berens acquired the Bentworth Hall estate, carvings of bears were put up in various places. Two of which can be seen at the entrance to the Bentworth Hall drive, between the two lodge houses. Herbert Berens died on 27 October 1981,[28] and the remaining estate was put up for sale. Initially Bentworth Hall was offered as a single property, but its outbuildings were divided into a number of separate dwelling units and other parts were sold to local farms.[22] In June 1982, the Bentworth Conservation Area was established, incorporating many of the local buildings of note, extending along the main lane and around the church.[29]

Bentworth was awarded a gold postbox in 2012 after Peter Charles, a resident of the village, won a gold medal in the equestrian event of the 2012 Summer Olympics. A postbox in Alton was incorrectly painted gold in Charles' honour, until the Royal Mail later painted the correct postbox in Bentworth.[30][31]

Governance

In elections for the United Kingdom national parliament, Bentworth is in the constituency of East Hampshire,[32] which since May 2010 has been represented by Damian Hinds of the Conservative Party.[33] Prior to Britain leaving the European Union in January 2020, it was part of the South East England constituency of the European Parliament.

In local government, Bentworth is governed by Hampshire County Council at the highest tier, East Hampshire District Council at the middle tier, and Bentworth Parish Council at the lowest tier. In County Council elections Hampshire is divided into 75 electoral divisions that return a total of 78 councillors;[34] Bentworth is in Alton Rural Electoral Division.[35] In district council elections East Hampshire is divided into 38 electoral wards that return a total of 44 councillors; Bentworth is in the Bentworth and Froyle Ward, together with the parishes of Lasham, Shalden, Wield and Froyle.[36]

Bentworth has its own nine-member parish council with responsibility for local issues,[37] including setting an annual local rate to cover the council's operating costs and producing annual accounts for public scrutiny.[38] The parish council evaluates local planning applications and works with Hampshire Constabulary, district council officers, and neighbourhood watch groups on matters of crime, security, and traffic. The council's role also includes initiating projects for the maintenance of parish facilities, as well as consulting with the district council on the repair and improvement of highways, drainage, footpaths and public transport.[39]

Geography

Bentworth village and parish lies on high downland about 3 miles (4.8 km) northwest of the town of Alton and about 9 miles (14 km) south of Basingstoke, the largest town in Hampshire. By road, Bentworth is situated 9.4 miles (15.1 km) south of Basingstoke, 16.7 miles (26.9 km) northeast of the county town of Winchester and 32 miles (51 km) north of Portsmouth.[40] The parish covers an area of 3,763 acres (15.23 km2); the soil is clay and loam, the subsoil chalk. In 1911 about 280 acres (1.1 km2) of the parish were woodland, and the most prominent crops were wheat, oats, and turnips.[4]

The lower ground to the south-east of Bentworth and to the south of the nearby villages of Lasham and Shalden drains towards the River Wey which rises to the surface near Alton.[41] Near Hall Place is the village duckpond, with cottages opposite it dated to 1733. Such names as Colliers Wood and Nancole Copse in the parish point to the early operations of the charcoal burners, the colliers of the Middle Ages.[4] Other woods in the area include Gaston Wood, Childer Hill Copse, Miller's Wood, Thedden Copse, Well Copse, North Wood, Wadgett's Copse, Bylander's Copse, Nancole Copse, Widgell Copse, South Lease Copse, Stubbins Copse and Mayhew's Wood.[40] The names of Windmill Field and Mill Piece indicate the site of one or more ancient mills.[4]

Parish background

The civil parish of Bentworth, starting to the north and working clockwise, extends from north of Burkham House, then runs south east along the A339, turns south to Thedden Grange and the hamlet of Wivelrod, then west to north of Medstead and north again to Ashley Farm and back to the Burkham area.[42]

Bentworth was the largest parish in the Hundred of Odiham, after Odiham itself. At the time of the Domesday Book the Hundred was included in two separate hundreds, Odiham and Hefedele (also known as Edefele and Efedele). The former comprised Lasham and Shalden and half a hide which had been taken from the nearby village of Preston Candover, and the latter included Odiham, Winchfield, Elvetham, Dogmersfield, and a former parish named Berchelei.[11] For the manors of Bentworth, Greywell, Hartley Wintney, Liss, Sherfield-upon-Loddon, and Weston Patrick, there are no entries in the Survey, but they were believed to have been included in the large manor of Odiham.[43]

Villages and hamlets

Within the Bentworth parish are several hamlets, the largest of which is Burkham to the north of the village. Other hamlets include Wivelrod to the southeast, Holt End and New Copse to the south, Thedden to the east, Ashley to the west and Tickley to the north.[44]

Burkham

Burkham (also known as Brocham (14th century); Barkham (16th century); Berkham (18th century)) is a larger hamlet on the north side of the parish of Bentworth that lies about 2.4 miles (3.9 km) northwest of the village. Burkham was first mentioned in 1111,[7] and was later mentioned as part of the Manor of Bentworth in documents of the Archbishop of Rouen around 1115, in which it is described as a "berewite" (an outlying estate) of the Bentworth Manor[12] Tickley is a smaller hamlet that lies approximately 1.1 miles (1.8 km) south of Burkham, which includes a manor house named Tickley House.[45]

Burkham is where Georgian Burkham House is located.[46] It was first recorded in a document dated 1784 in which there was a reference to a "Manor or Mansion House of Burkham", owned by Thomas Coulthard (1756–1811). Burkham House was acquired in 1882 by Arthur Frederick Jeffreys, later a member of parliament for Basingstoke.[47] Ownership was retained by the Jeffreys family until 1965 when the estate was put up for sale.[47]

The Home Farm area consists of 336 acres (136 ha) of farmland, copse and uncultivated land.[48] Part of this area between Burkham and Bentworth was bought by the Woodland Trust in 1990. Before the Woodland Trust purchased the property, it was scheduled to become a landfill.[49] The Trust planted trees in 1993. This is the only nature preserve in the area.[48]

Holt End and New Copse

Holt End and New Copse are two areas of Bentworth that lie to the south of the village. The word Holt means "a small grove of trees or wood",[50] and Holt End thus means the end of a wooded area. A long road to the south, called Jennie Green Lane, branches off the main road in Bentworth and runs northwest from Medstead to Lower Wield.[51] Gaston Grange and Holt Cottage, a small thatched cottage dating from 1503 and a Grade II listed building since 1985,[52] both lie within the hamlet.

Thedden

Thedden is a hamlet and part of the parish of Bentworth between the villages of Bentworth and Beech. Thedden Grange is about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) south-east of St Mary's Church and is a country house that was formerly part of the Bentworth Manor estate. During the Second World War, Thedden Grange was used as a prisoner of war camp.[24][25][lower-alpha 3] Thedden derivatives from the Anglo-Saxon name of "Tedena" and was first documented in 1168. The earliest map of Thedden was produced in 1676 by Lewis Andrewes, a surveyor for Magdalene College. At the time of the late 12th century, Thedden comprised 1,000 acres (400 ha) of "fertile land".[56]

Wivelrod

Wivelrod is a hamlet in the extreme south-east corner of the parish of Bentworth. Wivelrod was first mentioned in documents dating to 1259.[4] In the 18th century Wivelrod Manor belonged to the owner of Bentworth Hall, although some land, excluding the farm, was sold in the 1830s for £900, when the estate was bought by Roger Staples Horman Fisher.[4]

Demographics

In the 2011 census Bentworth parish had 228 dwellings,[57] 211 households and a population of 553 (270 males and 283 females).[58] The average age of residents was 43.3 (compared to 39.3 for England as a whole) and 20.3% of residents were age 65 or older (compared to 16.4% for England as a whole).[59]

At the time of the 2001 UK census, Bentworth had a total population of 466. For every 100 females, there were 94.2 males. The average household size was 2.50.[60] Of those aged 16–74 in Bentworth, 33.6% had no academic qualifications or one GCSE, lower than the figures for all of East Hampshire (37.1%) and England (45.5%).[61][62] According to the census, 29.9% were economically inactive and of the economically active people 1.3% were unemployed.[61] Of Bentworth's 466 residents, 18.5% were under the age of 16 and 14.2% were aged 65 and over; the mean age was 42.05. 78.8% of residents described their health as "good".[63]

| Population growth in the Parish of Bentworth since 1801 | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1801 | 1811 | 1821 | 1831 | 1841 | 1851 | 1881 | 1891 | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1951 | 1961 | 2001 | 2011 |

| Population | 425 | 406 | 548 | 592 | 609 | 610 | 558 | 604 | 571 | 586 | 522 | 570 | 614 | 596 | 466 | 553 |

| % change | – | −4.5 | +35.0 | +8.0 | +2.9 | +0.2 | −8.5 | +8.2 | −5.5 | +2.6 | −10.9 | +9.2 | +7.7 | −2.9 | −21.8 | +18.7 |

| Source: A Vision of Britain through Time, and statistics.gov.uk | ||||||||||||||||

The Domesday Book entry for the Hundred of Odiham surmised that the hundred in 1066 was very large with 248 households and recorded 138 villagers. 60 smallholders and 50 slaves.[64] Tax was assessed to be very large at 78.5 exemption units.[64] 56 ploughlands, 16.5 lord's plough teams and 41 men's plough teams were recorded.[64] The Lord of the hundred in 1066 was Earl Harold.[64] In 1808 the population of Bentworth was 425.[65] Bentworth had reached its population peak in 1951, with 614 people living in the village.

Education and activities

St Mary's Bentworth Primary School is immediately west of the church together with a school hall and playing field that are used for events such as the annual village fete. The school was built in 1848 with a single classroom; a second room to accommodate more pupils was added in 1871. The gallery was added in celebration of the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria in 1891.[2] As of 2015, the school had 87 pupils, not only from Bentworth but also from surrounding villages.[66]

The school hall is used for other village activities such as Bentworth Garden Club meetings,[67] performances by the Bentworth Mummers (a local amateur theatrical group), other meetings, and as a polling station for elections. In November 2010, the Bentworth Mummers put on a performance of Hans Christian Andersen's The Snow Queen.[68] Bentworth Cricket Club is just south of the village. The village has five tennis courts, one just to the south of the church and school, one just further to the southeast on the main village street, another at Hall Farm, and two more either side of the Sun Inn on Sun Hill.[40]

Notable landmarks

The following are the listed buildings in the Parish of Bentworth. The listings are graded:[69][lower-alpha 4]

- Barn 20 Metres South East of Parsonage Farmhouse (II)

- Barn 45 Metres North East of Weller's Place Farmhouse (II)

- Barn 55 Metres South West of Summerley (II)

- Bentworth Blackmeadow (II)

- Cartshed 35 Metres North of Hall Farmhouse (DL)

- Chapel Immediately West of Hall Farmhouse (II*)

- Church of St Mary (II*)

- Granary 20 Metres North West of Manor Lodge (II)

- Greensleeves (II)

- Half Barn 30 Metres North of Weller's Place Farmhouse (II)

- Hall Farmhouse (II*)

- Hankin Family Tomb in Churchyard of St Mary's Church (II)

- Holt Cottage (II)

- Hooker's Place (II)

- Hunt's Cottage (II)

- Ivall's (II)

- Ivall's Cottage (II)

- Ivall's Farmhouse (II)

- Linzey Cottage (II)

- Manor Lodge (II)

- Mulberry House (II)

- Penton Cottage (II)

- Service Block Attached to Manor Lodge (II)

- Stable Block 40 Metres North of Weller's Place Farmhouse (II)

- Strawtop (II)

- War Memorial in Churchyard of St Mary's Church (II)

- Wardies (II)

- Wivelrod Farmhouse (DL)

St Mary's Church and war memorial

The church of St Mary lies at the centre of the village immediately east of the Primary school, located about 150 metres (490 ft) north-east of the Star Inn. There is evidence to suggest that an Anglo-Saxon church was located here and was rebuilt.[4] The present church has a chancel (the space around the altar for the clergy and choir) that is 27 feet (8.2 m) by 17 feet 4 inches (5.28 m), with a north vestry measuring 48 feet 7 inches (14.81 m) by 17 feet (5.2 m).[4] The nave roof and chancel arch date from the late 12th century and the chancel itself was built in about 1260 together with the lower part of the tower.[71] The church suffered what historian Georgia Smith describes as a "fire happening by lightning from heaven", and some of the earlier structure was damaged. It was repaired in 1608.[7][12][72]

The present church has flint walls with stone dressings and stepped buttresses, a plinth, and corbelled tracer lights in the nave.[4] The west tower was rebuilt in 1890 and has diagonal buttresses with an elaborate arrangement of steps (some with gabled ornamentation), and at the top is a timber turret, surmounted by a broach spire. A small mural monument at the south-east of the chancel is to Nicholas Holdip, "pastor of the parish" in 1606, and his wife Alicia (Gilbert). The north aisle wall contains another mural tablet dedicated to "Robert Hunt of Hall Place in this Parish", 1671, with the arms, Azure a bend between two water bougets or with three leopards' heads gules on the bend. The crest is a talbot sitting chained to a halberd. There are four bells; the treble and second by Joseph Carter, 1601, the third by Henry Knight, 1615, and the tenor by Joseph Carter, 1607.[4] The church celebrated the coronation of King George V by adding a clock to the building.[2] It became a Grade II* listed building on 31 July 1963.[71]

Memorials

In Elizabethan times, the poet and writer George Wither (1588–1667) was born in Bentworth and baptised in St Mary's church.[8] In Victorian times, the author George Cecil Ives lived at the post-1832 Bentworth Hall with his mother Emma Gordon-Ives. A memorial to the Ives family is in the churchyard close to the school and has a stone slab for George Ives that reads "George Cecil Ives MA, author, 1867–1950, Late of Bentworth Hall." The stone slab for his mother reads "The Honourable Emma, wife of J.R. Ives, Daughter of Viscount Maynard Lord Lieutenant of Essex, died March 14, 1896 aged 84."

The Hankin Family Tomb in the churchyard, was Grade II listed in 2005.[73] It was made in 1816 of Portland stone and is a "rectangular chest tomb on a moulded base, with a two-part cover consisting of a low hipped top slab and lower moulded cornice."[73] The panels at the sides contain various inscriptions including the one on the south panel which reads: "Sacred to the memory of John Hankin who departed this life January 12, 1816, aged 55 years", and the one on the north side which reads: "Sacred to the memory of Elizabeth, widow of John Hankin, who departed this life September 13, 1831, aged 67 years."[73]

The churchyard contains two registered Commonwealth war graves, a soldier of the East Surrey Regiment of World War I,[74] and a Royal Navy officer of World War II.[75]

War Memorial

The War Memorial in the churchyard of St Mary's Church, made of Doulting limestone, was erected in 1920 by Messrs Noon and Company of Guildford on behalf of the parish to commemorate the local men who had lost their lives in the First World War.[76] The decision to build a memorial at the church was decided during a parish meeting on 7 February 1920 and it was formally dedicated on 28 November 1920 by the Reverend A.G. Bather and unveiled by Major General Jeffreys of Burkham, officer in command of the London District. The war memorial has a four-step base, with a "tapering octagonal shaft on a small square plinth block" placed upon it and a Latin cross at the top of the shaft.[76]

The dedication inscription on the top west facing step of the base reads: "Sacred to the men of Bentworth who fell in the Great War 1914–1918 leaving to us who pass where they passed an undying example of faithfulness and willing service."[76] There are four names inscribed on the top step panel facing south including the name of Lieutenant Colonel Neville Elliot-Cooper of the Royal Fusiliers (whose father lived in Bentworth) and several names on other steps. On the third step facing west, is the inscription: "1939–1945. And in second dedication to the memory of those others who passing later also fell leaving no less glorious name." The memorial was Grade II listed on 8 December 2005.[76]

Manor and Hall

Hall Place, formerly Bentworth Hall or Manor, is a Grade II* listed medieval hall-house, located south of the road to Medstead just south-west of Tinker's Lane. It was built in the early 14th century with additions in the 17th and 19th centuries.[77] The hall is believed to have been constructed by either the constable of Farnham Castle, William de Aula,[lower-alpha 5] or 'John of Bynteworth'.[77] The de Aula family are documented as being the first owners, followed by the de Melton family.[14]

The hall has thick flint walls, gabled cross wings,[78] with a Gothic stone arch and 20th century boarded door and two-storey porch. The west wing of the house has a stone-framed upper window and large attached tapered stack. The east wing has sashes dated to the early 19th century.[77] The old fireplace remains in the north, facing room with it roll moulding and steeply pitched head. A chapel in the grounds was part of the house complex.[14]

In 1832 the Bentworth Hall estate was sold to Roger Staples Horman Fisher and he started building the present Bentworth Hall.[72] Bentworth Hall is located approximately one mile south of the old hall at, some 500 metres (1,600 ft) east of hamlet of Holt End at the end of an 800 metres (870 yd) private drive. As of 2015, the lodge originally at the entrance to Bentworth Hall is no longer considered part of the property.[17] The great house was divided into four separate homes in 1983. The eastern wing of the property became Bentworth Court, the central portion of the house is now known as Bentworth Mews and the coach house and stables were offered separately.[79]

Gaston Grange

Gaston Grange is north of New Copse and south of Gaston Wood. This area was part of the Bentworth Hall estate and is now privately owned. In the late 19th century, Emma Gordon-Ives owned Bentworth Hall and in 1890 her son Colonel Gordon Maynard Gordon-Ives built Gaston Grange to the east of Bentworth Hall.[80] Gordon-Ives inherited Bentworth Hall upon the death of Emma in 1897, but continued to live at Gaston Grange until his death.[81] In 1914, his son Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Gordon lived in Gaston Grange. He served in the First World War and was an Ulster Unionist Party Member and Senator in the Parliament of Northern Ireland, dying in April 1967.[82] After his death, the Bentworth Hall Estate was offered for sale by Messrs John D Wood & Co. and at this time consisted of 479 acres (194 ha). Gaston Grange has been extensively renovated and modernised in recent times; new inclusions are entrance and reception halls, three reception rooms and a grand staircase. Today, the Gaston Grange estate consists of 198 acres (80 ha).[81]

Mulberry House

Mulberry House is a late Georgian building, dated to 1818. It served as Bentworth's rectory and became a Grade II listed building on 31 July 1963.[83] The house has stucco walls, with painted brickwork and a slate roof. It is a square two-storey building, with a symmetrical front consisting of three windows, a doric columned porch, half-glazed doors and a low-pitched hipped roof, with a raised lead flat in the centre.[83] The current rectory is a smaller, modern house on the other side of the main road through the village, opposite Mulberry House.[84]

Ivalls and Holt Cottages

Ivall's Cottage, a Grade II listed building since 1985, is located opposite the post box near the village green. The cottage was originally built during the 16th century, with late 18th century and early 19th century additions with contemporary extensions at the sides.[85] The cottage is built from red brick and flint in Flemish bond, with cambered openings on the ground floor with a part-thatched, part-tiled roof. The roof is hipped at the west end, with lower eaves at the rear intercepted by eyebrow dormers.[85]

Ivall's Farm House is on the south side of the road near the Star Inn. It is a timber framed and cruck-built (A-frame) tiled roof building with a lobby entrance, previously a farmhouse, originally built around 1600. The south end dates to the 18th century.The tiled roof, with four small gabled dormers, half-hipped at the north west angle, was restored in the late 20th century. It became a Grade II listed building on 31 July 1963.[86] Holt Cottage is a small thatched cottage situated on the edge of the village and was built in 1503. A Grade II listed building since 31 May 1985, much of the current building dates to the 17th and early 19th centuries. The roof is half-hipped at the south end and hipped at the north, with painted brickwork in monk bond.[52]

Public houses

Near the centre of the village are two public houses: the Star Inn, which was licensed in 1848,[12][87] opposite the village green, and the Sun Inn, which was licensed beginning in 1838,[12][88] which sits at the top of Sun Hill, on the road to Alton.[40][89] There was a third pub in the village called the Moon Inn (also known as the Half Moon) which was demolished around 1948;[12][2][72] just north of the church in Drury Lane.

Transport

The nearest railway station is 3.6 miles (5.8 km) east of the village, at Alton.

Between 1901 and 1932 Bentworth & Lasham station was available to passenger traffic on the Basingstoke and Alton Light Railway. It was located just north of the present A339 road between Bentworth and Lasham and was designed by John Wallis Titt.[90][91] The station opened on 1 June 1901 and closed during the First World War on 1 January 1917.[92] The line was reopened in 1924 as area residents pressed for the reopening of the railway.[93] It stayed open until 1931 when the railway announced it would no longer carry passengers.[94] The railway transported only goods until its final closure in 1936.[95]

Alton was on the South West Main Line from London Waterloo to Winchester and Basingstoke was on the West of England Main Line from London Waterloo to Salisbury.[96][97]

In the 1960s, the connection between Alton and Winchester was broken because of railway closures and the construction of the M3 motorway east of Winchester.[98][99][100] As of 2015, the line continues west of Alton to Alresford as the "Watercress Line" or Mid Hants Railway, running historic steam engines.[101] The level crossing between Bentworth and Lasham appeared in the 1929 film The Wrecker and the line was also used in the 1937 film Oh, Mr Porter!.[102] The small station waiting room was demolished in 2003.[103]

Notable people

The poet and satirist George Wither (1588–1667) was born in Bentworth.[104] He was baptised in St Mary's Church and later, supporting Oliver Cromwell's cause during the English Civil War, sold land in the parish to raise a troop of horses for the Roundhead (anti-Royalist) cause.[105][106] The Wither family lived in Bentworth until the 17th century.[107] In his 1613 satirical poem Abuses Stript and Whipt, Wither mentions his early life in Bentworth and alludes to the "beechy shadows" of the village.[4][108]

George Cecil Ives (1867–1950), an author, criminologist and homosexual law reform campaigner,[109] spent time at the family home at Bentworth Hall.[110]

Further reading

- Smith, Georgia Bentworth: The making of a Hampshire Village. Bentworth Parochial Church Council. 1988. ISBN 0 9513653 0 4.

- Uncredited St Mary's Church, Bentworth Available from the church

References

Notes

- ↑ A third, the Moon Inn, was demolished around 1948.[2]

- ↑ See the section on "Memorials" for a photo of the Gordon-Ives family plaque inside Bentworth Church on the north wall.

- ↑ Durley village had a historical society, Durley History Society, which published newsletters. An article about the POW camps appeared in its January 2009 issue which mentions Thedden Grange.[53] The Durley History Society claimed that another POW camp existed with the name of Fishers Camp and that it was not located at Thedden Grange.[54][55] The Guardian published a 2010 article claiming that Thedden Grange was the site of Fishers Camp.[25]

- ↑ There are three types of listed status for buildings in England and Wales:

- Grade I: buildings of exceptional interest.

- Grade II*: particularly important buildings of more than special interest.

- Grade II: buildings that are of special interest, warranting every effort to preserve them.[70]

- ↑ Also known as William Bentworth.[14]

Citations

- 1 2 "Civil Parish population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Cross 2013.

- ↑ Shore 1899, p. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Page 1911, pp. 68–71.

- ↑ Curtis 1906, p. 19.

- ↑ Ekwall 1960, pp. 38, 41–42.

- 1 2 3 4 "Bentworth statistical findings" (PDF). Bentworth.org. East Hampshire District Council. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "Bentworth", Hampshire Treasures, Hampshire County Council, 6: 37, archived from the original on 29 February 2012, retrieved 14 April 2010

- ↑ "Minor Romano-British Settlement". Roman Britain.org. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ↑ "Neatham". Old Hampshire Gazetteer. University of Portsmouth Information Services. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 Page 1911, pp. 66–67.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Bentworth Parish Plan" (PDF). Bentworth Parish Council. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 June 2015.

- ↑ Vincent 2002, p. 72.

- 1 2 3 4 Emery 2006, pp. 310–311.

- ↑ Wheater 1882, p. 152.

- ↑ Irvine 2007, p. 71.

- 1 2 "Bentworth Hall". Hampshire Gardens Trust. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ↑ Burke 1858, p. 618.

- ↑ "The Papers of George Cecil Ives". Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ↑ Smith 1899, pp. 291–293.

- ↑ Wilson 1870, p. 194.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Bentworth Hall overview". Hampshire Garden Trust. PB Works. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ↑ Burke 1925, p. 54.

- 1 2 "Thedden Grange and Park". Hampshire Gardens Trust. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 Rogers, Simon (8 November 2010). "Every prisoner of war camp in the UK mapped and listed". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ↑ "History of Complins" (PDF). The Holybourne Village Magazine: 13–16. 2005. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ↑ Grossman 1972, p. 90.

- ↑ "Obituaries in 1981". ESPN. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ↑ "Bentworth Conservation Area" (PDF). East Hampshire District Council. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ↑ "'Wrong' postbox painted gold in honour of Olympian Peter Charles". BBC News. BBC. 8 August 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ↑ "Wrong Postbox Painted Gold". Heart, Hampshire. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ "Election Maps". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ↑ "Damian Hinds MP". www.parliament.uk. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ↑ "Elections". Hampshire County Council. Archived from the original on 26 July 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ↑ "Have your say on new county division boundaries for Hampshire". The Local Government Boundary Commission for England. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ↑ "Bentworth & Froyle". East Hampshire Conservatives. Archived from the original on 31 January 2023. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

- ↑ "Bentworth Parish Council homepage". Bentworth Parish Council. Archived from the original on 10 July 2023. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

- ↑ "Bentworth Parish Council Financial Regulations" (PDF). Bentworth Parish Council. 3 May 2022. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

- ↑ Sharman, Laura (5 November 2013). "Parish council responsibilities". LocalGov. Hemming Information Services. Archived from the original on 16 March 2023. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Maps (Map). Google Maps.

- ↑ "The River Wey North Branch From Source (Alton) to Farnham". Wey River. Alton Herald. 11 July 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ↑ "Bentworth Hampshire". Vision of Britain.org.uk. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ↑ MacGregor & Stapleton 1983, pp. 14–17.

- ↑ White, Harold J. Osborne (1910). The Geology of the Country around New Alresford. Printed for H.M. Stationery Off., by Darling & Son. p. 52. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ↑ "Tickley House". Pentalocal. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ↑ "Parks and Gardens UK". Parksandgardens.ac.uk. 29 January 2009. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- 1 2 "History of Burkham House". parksandgardens.org. Parks and Gardens Data Services. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- 1 2 "Home Farm Management Plan: 2013–2018" (PDF). Woodland Trust. p. 18. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- ↑ "Burkham House". Hampshire Gardens Trust. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ↑ Galfridius & Way 1865, p. 244.

- ↑ "Jennie Green Lane overview". Modern-Day Explorers. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- 1 2 "Holt Cottage Bentworth". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ↑ "Durley History Society". Hampshire County Council. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ↑ "Holybourne Summer Issue" (PDF). The Holybourne Village Magazine. 2005. p. 15. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ↑ "Overview of Thedden". Hampshire HGardens Trust. March 2001. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ↑ "Area: Bentworth (Parish). Dwellings, Household Spaces and Accommodation Type, 2011 (KS401EW)". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ↑ "Area: Bentworth (Parish). Key Figures for 2011 Census: Key Statistics". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ↑ "Area: Bentworth (Parish). Age Structure, 2011 (KS102EW)". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- ↑ "Area: Bentworth CP (Parish) Parish Headcounts". Statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- 1 2 "Area: Bentworth CP (Parish) Work and Qualifications". Statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ↑ "Area: East Hampshire (Local Authority) Qualifications". Statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ↑ "Area: Bentworth CP (Parish) People". Statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 "Odiham". Domesday Map.co.uk. Archived from the original on 20 April 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ↑ Capper 1808, p. G3.

- ↑ "Welcome!". St Mary's Bentworth Primary School. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ↑ "Bentworth Garden Club". Bentworth.info. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ↑ "Bentworth Mummers are performing again". Bentworth.info. 23 October 2010. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ↑ "Listed Buildings in Bentworth, Hampshire, England". British Listed Buildings. 15 February 2012.

- ↑ "Listed Buildings". Historic England. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- 1 2 "St Mary's Church, Bentworth". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- 1 2 3 Bentworth: The Making of a Hampshire Village. Bentworth Parochial Church Council. 1988. ISBN 978-0-9513653-0-4.

- 1 2 3 "Hankin Family Tomb in the Churchyard of St Mary's Church, Bentworth". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ↑ CWGC Casualty record, Private Frederick Andrews.

- ↑ CWGC Casualty record, Commander Guy L'Estrange Mansfield Sturges.

- 1 2 3 4 "War Memorial in Churchyard of St Mary's Church, Bentworth". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Hall Farmhouse, Bentworth". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ↑ "Hall Farm, Bentworth, Alton, Hampshire" (PDF). Thames Valley Archaeological Services. p. 3. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ↑ Crawford, David (12 February 1983). "Houses that do the splits". The Guardian. p. 24. (subscription required)

- ↑ Papers by Command, Volume 83. House of Commons. 1947. p. 24. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- 1 2 "Hampshire's country houses set the pace". Country Life. 10 July 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ↑ Boothroyd, David. "Stormont Biographies". Politico's Guide to the History of British Political Parties. Archived from the original on 7 May 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- 1 2 "Mulberry House, Bentworth". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ↑ "St Andrew's Medstead: Rectory of Bentworth". St Andrew's, Medstead. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- 1 2 "Ivalls Cottage, Bentworth". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ↑ "Ivalls Farmhouse, Bentworth". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ↑ "Star Inn, Bentworth". Star Inn. Archived from the original on 18 December 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ↑ "The Sun Inn, Bentworth". Sun Inn. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ↑ Miller, Wendy (20 October 2007). "Hampshire Pub Guide: The Sun Inn, Bentworth". The Daily Telegraph.

- ↑ Griffith 1982, p. 16.

- ↑ "Wind and Water". Colonel Stephens Railway. Colonel Stephens Museum. 2001. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ↑ "Basingstoke and Alton Light Railway". Hampshire Railways. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ↑ Engel 2010, p. 183.

- ↑ Kidner 1958, p. 36.

- ↑ Holland 2013, p. 63.

- ↑ Andrews 2004, p. 284.

- ↑ Transport in the South West. Parliament House of Commons. 2009. p. 197. ISBN 9780215544117. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ↑ Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons (1973). Parliamentary debates: Official report. H.M. Stationery Off. p. 421. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ↑ "The end of the line for southern steam". BBC Hampshire and Isle of Wight. BBC. 10 October 2008. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ↑ Conway, Peter. "Railway History: Lines we lost – and ones we didn't". Railway History. Saturday Walkers Club. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ↑ Awdry & Cook 1979, pp. 52–51, 224.

- ↑ The Railway Magazine. IPC Business Press. 1983. p. 42. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ↑ Crist Bal, Barnabas (2012). Bentworth and Lasham Railway Station. Cede Publishing. p. 108. ISBN 9786136819396. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ Goodrich 1832, p. 517.

- ↑ "Bentworth summary". Southern Life. Archived from the original on 28 February 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ↑ Bigg-Wither 1907, p. 154.

- ↑ Smith, Elder (1902). The Cornhill Magazine. William Makepeace Thackeray. p. 538.

- ↑ Bigg-Wither 1907, p. 95.

- ↑ Cook, Matt (2007), "Ives, George Cecil (1867–1950)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.), Oxford University Press, retrieved 9 September 2015 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ↑ Stokes 1996, pp. 66–7.

Bibliography

- Who was who: a companion to Who's who : containing the biographies of those who died during the period, Volume 2. A & C Black. 1967.

- Andrews, Robert (April 2004). Rough Guide to England. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-84353-249-1.

- Awdry, W.; Cook, Chris (1979). A Guide to the Steam Railways of Great Britain. Pelham. ISBN 978-0-7207-1052-6.

- Bigg-Wither (1907). A History of the Wither Family. Reginald Fitz Hugh Bigg-Wither. ISBN 9781425137830.

- Burke, Bernard (1858). A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Landed Gentry of Great Britain and Ireland, Volume 1. Harrison.

- Burke, Bernard (1925). A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Landed Gentry of Great Britain and Ireland. Burke Publishing Company.

- Burtt, Frank (1948). L & SWR locomotives, 1872–1923. I. Allan.

- Capper, Benjamin Pitts (1808). A Topographical Dictionary of the United Kingdom. Philips.

- Cross, Tony (2013). Alton and Its Villages Through Time. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4456-2652-9.

- Curtis, William (1906). The town of Alton. Oxford University.

- Ekwall, Eilert (1960). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place Names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-869103-7.

- Emery, Anthony (2006). Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300–1500: Volume 3, Southern England. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58132-5.

- Engel, Matthew (2010). Eleven Minutes Late: A Train Journey to the Soul of Britain. Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-2307-4041-9.

- Galfridius, Angelicus; Way, Albert (1865). Promptorium parvulorum sive clericorum: dictionarius anglo-latinus princeps. Sumptibus Societatis Camdenensi.

- Goodrich, Samuel Griswold (1832). Popular Biography: Embracing the Most Eminent Characters of Every Age, Nation, and Profession, Including Painters, Poets, Philosophers, Politicians, Heroes, Warriors. Leavitt & Allen. p. 517.

- Griffith, Edward C. (1982). The Basingstoke and Alton Light Railway, 1901–1936. Kingfisher Railway Productions.

- Grossman, David (1972). Who's who in British Finance. R. R. Bowker Company. ISBN 9780716100751.

- Shore, T. W. (1899). "Bentworth and its historical associations". Papers and Proceedings of the Hampshire Field Club and Archaeological Society. 4 (1): 1–15.

- Holland, Julian (2013). Dr Beeching's Axe: 50 Years on : Illustrated Memories of Britain's Lost Railways. David & Charles. ISBN 978-1-4463-0267-5.

- Irvine, Valerie (2007). The King's Wife: George IV and Mrs Fitzherbert. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-84725-053-7.

- Kidner, Roger Wakely (1958). The Southern Railway. Surrey, Oakwood Press.

- MacGregor, Patricia; Stapleton, Barry (1983). Odiham Castle, 1200–1500: castle and community. A. Sutton. ISBN 978-0-86299-030-5.

- Smith, F. J. (1899). "The Working of the Light Railways Act, 1896". Transactions. 31: 263–310.

- Smith, Georgia (1988). Bentworth: The Making of a Hampshire Village. Bentworth Parochial Church Council. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-9513653-0-4. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- Stokes, John (14 March 1996). Oscar Wilde: Myths, Miracles and Imitations. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47537-2.

- Page, William (1911). A History of the County of Hampshire: Volume 4. Victoria County History.

- Vincent, Nicholas (2002). Peter Des Roches: An Alien in English Politics, 1205–1238. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52215-1.

- Wheater, William (1882). The History of the Parishes of Sherburn and Cawood, with Notices of Wistow, Saxton, Towton, Etc. Longmans, Green, & Company.

- Wilson, John Marius (1870). The Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales. A. Fullarton.

External links

- Bentworth Parish Council

- Bentworth Conservation Area (East Hampshire District Council leaflet)

- Bentworth CP (Parish) (Office for National Statistics)

- Hampshire Treasures Volume 6 (East Hampshire) Pages 35, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42

- British History Online – Bentworth