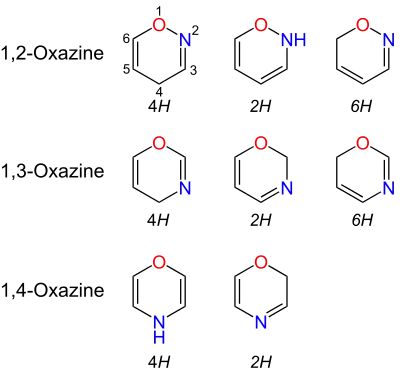

Oxazines are heterocyclic organic compounds containing one oxygen and one nitrogen atom in a cyclohexa-1,4-diene ring (a doubly unsaturated six-membered ring). Isomers exist depending on the relative position of the heteroatoms and relative position of the double bonds.

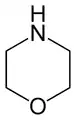

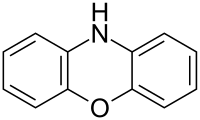

By extension, the derivatives are also referred to as oxazines; examples include ifosfamide and morpholine (tetrahydro-1,4-oxazine). A commercially available dihydro-1,3-oxazine is a reagent in the Meyers synthesis of aldehydes. Fluorescent dyes such as Nile red and Nile blue are based on the aromatic compound benzophenoxazine. Cinnabarine and cinnabaric acid are two naturally occurring dioxazines, being derived from biodegradation of tryptophan.[2]

Dioxazines

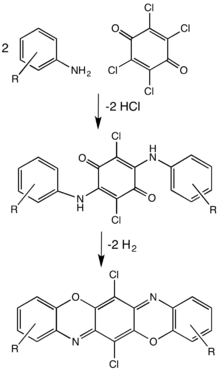

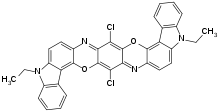

Dioxazines are pentacyclic compounds consisting of two oxazine subunits. A commercially important example is the pigment pigment violet 23.[3]

Benzoxazines

Benzoxazines are bicyclic compounds formed by the ring fusion of a benzene ring with an oxazine. Polybenzoxazines are a class of polymers formed by the reaction of phenols, formaldehyde, and primary amines which on heating to ~200 °C (~400 °F) polymerise to produce polybenzoxazine networks.[5] The resulting high molecular weight thermoset polymer matrix composites are used where enhanced mechanical performance, flame and fire resistance compared to epoxy and phenolic resins is required.[6]

Physical properties

Oxazine dyes exhibit solvatochromism.[7]

Images

Pigment violet 23 is a commercially useful pigment.

Pigment violet 23 is a commercially useful pigment.

References

- ↑ Eicher T, Hauptmann S, Speicher A (March 2013). The Chemistry of Heterocycles: Structures, Reactions, Synthesis, and Applications (3rd ed.). Wiley Inc. p. 442. ISBN 978-3-527-66987-5. OCLC 836864122.

- ↑ Stone TW, Stoy N, Darlington LG (February 2013). "An expanding range of targets for kynurenine metabolites of tryptophan" (PDF). Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 34 (2): 136–43. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2012.09.006. PMID 23123095.

- ↑ Chamberlain T (2002). "Dioxazine violet pigments". In Smith HM (ed.). High Performance Pigments. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 185–194. doi:10.1002/3527600493.ch12. ISBN 978-3-527-30204-8.

- ↑ Tappe H, Helmling W, Mischke P, Rebsamen K, Reiher U, Russ W, Schläfer L, Vermehren P (2000). "Reactive Dyes". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a22_651. ISBN 3527306730.

- ↑ Tsotra P, Setiabudi F, Weidmann U (2008). "Benzoxazine chemistry: a new material to meet fire retardant challenges of aerospace interiors applications" (PDF). Engineering. S2CID 18422389.

- ↑ Tietze R, Chaudhari M (2011). "Advanced benzoxazine chemistries provide improved performance in a broad range of applications". In Ishida H, Agag T (eds.). Handbook of Benzoxazine Resins. Elsevier B.V. pp. 595–604. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-53790-4.00079-5. ISBN 978-0-444-53790-4.

- ↑ Fleming S, Mills A, Tuttle T (2011-04-15). "Predicting the UV-vis spectra of oxazine dyes". Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry. 7: 432–441. doi:10.3762/bjoc.7.56. PMC 3107493. PMID 21647257.

External links

- Oxazines at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Development of polymeric materials as a class of benzoxazines