| Berengar of Friuli | |

|---|---|

| Emperor of the Romans | |

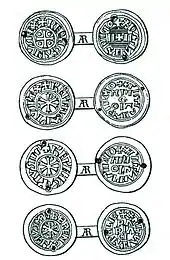

Berengar's imperial seal | |

| Emperor in Italy | |

| Reign | 915–924 |

| Coronation | December 915, Rome |

| Predecessor | Louis the Blind |

| Successor | Otto I |

| Born | c. 845 Cividale, Middle Francia |

| Died | 7 April 924 Verona, Kingdom of Italy |

| Spouse | Bertila of Spoleto; Anna |

| Issue | Bertha, Abbess of Santa Giulia in Brescia Gisela, Countess of Ivrea |

| House | Unruochings |

| Father | Eberhard of Friuli |

| Mother | Gisela, daughter of Louis the Pious |

Berengar I (Latin: Berengarius, Perngarius; Italian: Berengario; c. 845 – 7 April 924[1]) was the king of Italy from 887. He was Holy Roman Emperor between 915 and his death in 924. He is usually known as Berengar of Friuli, since he ruled the March of Friuli from 874 until at least 890, but he had lost control of the region by 896.[2]

Berengar rose to become one of the most influential laymen in the empire of Charles the Fat, and he was elected to replace Charles in Italy after the latter's deposition in November 887. His long reign of 36 years saw him opposed by no less than seven other claimants to the Italian throne. His reign is usually characterised as troubled because of the many competitors for the crown and because of the arrival of Magyar raiders in Western Europe. His death was followed by an imperial interregnum that lasted 38 years until Otto I was crowned emperor in 962.

Margrave of Friuli, 874–887

His family was called the Unruochings after his grandfather, Unruoch II. Berengar was a son of Eberhard of Friuli and Gisela, daughter of Louis the Pious and his second wife Judith. He was thus of Carolingian extraction on his mother's side. He was born probably at Cividale. Sometime during his margraviate, he married Bertilla, daughter of Suppo II, thus securing an alliance with the powerful Supponid family.[3] She would later rule alongside him as a consors, a title specifically denoting her informal power and influence, as opposed to a mere coniunx, wife.[4]

When his older brother Unruoch III died in 874,[5] Berengar succeeded him in the March of Friuli.[6] With this he obtained a key position in the Carolingian Empire, as the march bordered the Croats and other Slavs who were a constant threat to the Italian peninsula. He was a territorial magnate with lordship over several counties in northeastern Italy. He was an important channel for the men of Friuli to get access to the emperor and for the emperor to exercise authority in Friuli. He even had a large degree of influence on the church of Friuli. In 884–885, Berengar intervened with the emperor on behalf of Haimo, Bishop of Belluno.[7]

When, in 875, the Emperor Louis II, who was also King of Italy, died, having come to terms with Louis the German whereby the German monarch's eldest son, Carloman, would succeed in Italy, Charles the Bald of West Francia invaded the peninsula and had himself crowned king and emperor.[8] Louis the German sent first Charles the Fat, his youngest son, and then Carloman himself, with armies containing Italian magnates led by Berengar, to possess the Italian kingdom.[8][9] This was not successful until the death of Charles the Bald in 877. The proximity of Berengar's march to Bavaria, which Carloman already ruled under his father, may explain their cooperation.

In 883, the newly succeeded Guy III of Spoleto was accused of treason at an imperial synod held at Nonantula late in May.[10] He returned to the Duchy of Spoleto and made an alliance with the Saracens. The emperor, then Charles the Fat, sent Berengar with an army to deprive him of Spoleto. Berengar was successful before an epidemic ravaged all Italy, affecting the emperor and his entourage as well as Berengar's army, and forced him to retire.[10]

In 886, Liutward, Bishop of Vercelli, took Berengar's sister from the nunnery of San Salvatore at Brescia in order to marry her to a relative of his; whether or not by force or by the consent of the convent and Charles the Fat, her relative, is uncertain.[11] Berengar and Liutward had a feud that year, which involved his attack on Vercelli and plundering of the bishop's goods.[12] Berengar's actions are explicable if his sister was abducted by the bishop, but if the bishop's actions were justified, then Berengar appears to have initiated the feud. Whatever the case, bishop and margrave were reconciled shortly before Liutward was dismissed from court in 887.[12]

By his brief war with Liutward, Berengar had lost the favour of his cousin the emperor. Berengar came to the emperor's assembly at Waiblingen in early May 887.[13] He made peace with the emperor and compensated for the actions of the previous year by dispensing great gifts.[13] In June or July, Berengar was again at the emperor's side at Kirchen, when Louis of Provence was adopted as the emperor's son.[14] It is sometimes alleged that Berengar was pining to be declared Charles' heir and that he may in fact have been so named in Italy, where he was acclaimed (or made himself) king immediately after Charles' deposition by the nobles of East Francia in November that year (887).[15] On the other hand, his presence may merely have been necessary to confirm Charles' illegitimate son Bernard as his heir (Waiblingen), a plan which failed when the pope refused to attend, and then to confirm Louis instead (Kirchen).[16]

King of Italy, 887–915

Berengar was the only one of the reguli (petty kings) to crop up in the aftermath of Charles' deposition besides Arnulf of Carinthia, his deposer, who was made king before the emperor's death.[17] Charter evidence begins Berengar's reign at Pavia, in the Basilica of San Michele Maggiore,[18] between 26 December 887 and 2 January 888, though this has been disputed.[19] Berengar was not the undisputed leading magnate in Italy at the time, but he may have made an agreement with his former rival, Guy of Spoleto, whereby Guy would have West Francia and he Italy on the emperor's death.[20] Both Guy and Berengar were related to the Carolingians in the female line. They represented different factions in Italian politics: Berengar the pro-German and Guy the pro-French.

In Summer 888, Guy, who had failed in his bid to take the West Frankish throne, returned to Italy to gather an army from among the Spoletans and Lombards and oppose Berengar. This he did, but the battle they fought near Brescia in the fall was a slight victory for Berengar, though his forces were so diminished that he sued for peace nevertheless.[21] The truce was to last until 6 January 889.[21]

After the truce with Guy was signed, Arnulf of Germany endeavoured to invade Italy through Friuli. Berengar, in order to prevent a war, sent dignitaries (leading men) ahead to meet Arnulf. He himself then had a meeting, sometime between early November and Christmas, at Trent.[21] He was allowed to keep Italy, as Arnulf's vassal, but the curtes of Navus and Sagus were taken from him.[22] Arnulf allowed his army to return to Germany, but he himself celebrated Christmas in Friuli, at Karnberg.[23]

Early in 889, their truce having expired, Guy defeated Berengar at the Battle of the Trebbia and made himself sole king in Italy, though Berengar maintained his authority in Friuli.[24] Represented by his counsellor Walfred at the city of Verona, he remained master in Friuli, which was always the base of his support. Though Guy had been supported by Pope Stephen V since before the death of Charles the Fat, he was now abandoned by the pope, who turned to Arnulf. Arnulf, for his part, remained a staunch partisan of Berengar and it has even been suggested that he was creating a Carolingian alliance between himself and Louis of Provence, Charles III of France, and Berengar against Guy and Rudolph I of Upper Burgundy.[25]

In 893, Arnulf sent his illegitimate son Zwentibold into Italy. He met up with Berengar and together they cornered Guy at Pavia, but did not press their advantage (it is believed that Guy bribed them off). In 894, Arnulf and Berengar defeated Guy at Bergamo and took control of Pavia and Milan. Berengar was with Arnulf's army that invaded Italy in 896. However, he left the army while it was sojourning in the March of Tuscany and returned to Lombardy.[26] A rumour spread that Berengar had turned against the king and had brought Adalbert II of Tuscany with him.[26] The truth or falsehood of the rumour cannot be ascertained, but Berengar was removed from Friuli and replaced with Waltfred, a former supporter and highest counsellor of Berengar's, who soon died.[27] The falling out between Berengar and Arnulf, who was crowned Emperor in Rome by Pope Formosus, has been likened to that between Berengar II and Otto I more than half a century later.[28]

Arnulf left Italy in the charge of his young son Ratold, who soon crossed Lake Como to Germany, leaving Italy in the control of Berengar, who made a pact with Lambert, Guy's son and successor.[29] According to the Gesta Berengarii Imperatoris, the two kings met at Pavia in October and November and agreed to divide the kingdom, Berengar receiving the eastern half between the Adda and the Po, "as if by hereditary right" according to the Annales Fuldenses. Bergamo was to be shared between them. This was a confirmation of the status quo of 889. It was this partitioning which caused the later chronicler Liutprand of Cremona to remark that the Italians always suffered under two monarchs. As surety for the accord, Lambert pledged to marry Gisela, Berengar's daughter.

The peace did not last long. Berengar advanced on Pavia, but was defeated by Lambert at Borgo San Donnino and taken prisoner. Nonetheless, Lambert died within days, on 15 October 898. Days later Berengar had secured Pavia and become sole ruler.[30] It was during this period that the Magyars made their first attacks on Western Europe. They invaded Italy first in 899. This first invasion may have been unprovoked, but some historians have suspected that the Magyars were either called in by Arnulf, no friend of Berengar's, or by Berengar himself, as allies.[31] Berengar gathered a large army to meet them and refused their request for an armistice. His army was surprised and routed near the Brenta River in the eponymous Battle of the Brenta (24 September 899).[32]

This defeat handicapped Berengar and caused the nobility to question his ability to protect Italy. As a result, they supported another candidate for the throne, the aforementioned Louis of Provence, another maternal relative of the Carolingians. In 900, Louis marched into Italy and defeated Berengar; the following year he was crowned Emperor by Pope Benedict IV. In 902, however, Berengar struck back and defeated Louis, making him promise never to return to Italy. When he broke this oath by invading the peninsula again in 905, Berengar defeated him at Verona, captured him, and ordered him to be blinded on 21 July.[33] Louis returned to Provence and ruled for another twenty years as Louis the Blind. Berengar thereby cemented his position as king and ruled undisputed, except for a brief spell, until 922. As king, Berengar made his seat at Verona, which he heavily fortified.[34] During the years when Louis posed a threat to Berengar's kingship, his wife, Bertilla, who was a niece of the former empress Engelberga, Louis's grandmother, played an important part in the legitimisation of his rule.[4] She later disappeared from the scene, as indicated by her absence in his charters post-905.

In 904, Bergamo was subjected to a long siege by the Magyars. After the siege, Berengar granted the bishop of the city walls and the right to rebuild them with the help of the citizens and the refugees fleeing the Magyars.[35] The bishop attained all the rights of a count in the city.

Emperor, 915–924

In January 915, Pope John X tried to forge an alliance between Berengar and the local Italian rulers in hopes that he could face the Saracen threat in southern Italy. Berengar was unable to send troops, but after the great Battle of the Garigliano, a victory over the Saracens, John crowned Berengar as Emperor in Rome (December).[36] Berengar, however, returned swiftly to the north, where Friuli was still threatened by the Magyars.

As emperor, Berengar intervened in an episcopal election in the diocese of Liège, outside of the kingdom of Italy.[37] After the death of the saintly Bishop Stephen in 920, Herman I, Archbishop of Cologne, representing the German interests in Lotharingia, tried to impose his choice of the monks of the local cloister, one Hilduin, on the vacant see. The clergy opposed to this interference appealed to Berengar, King Charles III of France and Pope John.[38] In the end, the pope excommunicated Hilduin and another monk, Richer, was appointed to the see with the support of the emperor.

In his latter years, his wife Bertilla was charged with infidelity, a charge not uncommon against wives of declining kings of that period.[39] She was poisoned.[40] He had remarried to one named Anna by December 915.[40] It has been suggested, largely for onomastic reasons, that Anna was a daughter of Louis of Provence and his wife Anna, the possible daughter of Leo VI the Wise, Byzantine Emperor.[41] In that case, she would have been betrothed to Berengar while still a child and only become his consors and imperatrix in 923.[41] Her marriage was an attempt by Louis to advance his children while he himself was being marginalised and by Berengar to legitimise his rule by relating himself by marriage to the house of Lothair I which had ruled Italy by hereditary right since 817.

By 915, Berengar's elder daughter, Bertha, was abbess of Santa Giulia in Brescia, where her aunt had once been a nun. In that year, the following year, and in 917, Berengar endowed her monastery with three privileges to build or man fortifications.[42] His younger daughter, Gisela of Friuli, had married Adalbert I of Ivrea as early as 898 (and no later than 910), but this failed to spark an alliance with the Anscarids.[43] She was dead by 913, when Adalbert remarried.[43] Adalbert was one of Berengar's earliest internal enemies after the defeat of Louis of Provence. He called on Hugh of Arles between 917 and 920 to take the Iron Crown.[43] Hugh did invade Italy, with his brother Boso, and advanced as far as Pavia, where Berengar starved them into submission, but allowed them to pass out of Italy freely.[44]

Dissatisfied with the emperor, who had ceased his policy of grants and family alliances in favour of paying Magyar mercenaries, several Italian nobles – led by Adalbert and many of the bishops – invited Rudolph II of Upper Burgundy to take the Italian throne in 921.[45] Moreover, his own grandson, Berengar of Ivrea (who would rule as Berengar II of Italy from 950), rose up against him, incited by Rudolph. Berengar retreated to Verona and had to watch sidelined as the Magyars pillaged the country.[46] John, Bishop of Pavia, surrendered his city to Rudolph in 922 and it was sacked by the Magyars in 924.[47] On 29 July 923, the forces of Rudolph, Adalbert, and Berengar of Ivrea met those of Berengar and defeated him in the Battle of Fiorenzuola, near Piacenza.[48] The battle was decisive and Berengar was de facto dethroned and replaced by Rudolf. Berengar was soon after murdered at Verona by one of his own men, possibly at Rudolph's instigation. He left no sons, only two daughters, Bertha and Gisela.[49]

Berengar has been accused of having "faced [the] difficulties [of his reign] with particular incompetence,"[50] having "never once won a pitched battle against his rivals,"[51] and being "not recorded as having ever won a battle" in "forty years of campaigning."[52] Particularly, he has been seen as alienating public lands and districtus (defence command) to private holders, especially bishops, though this is disputed.[53] Some historians have seen his "private defense initiatives" in a more positive light and have found a coherent policy of gift giving.[54] Despite this, his role in inaugurating the incastellamento of the succeeding decades is hardly disputed.[55]

References

- ↑ Rosenwein, p. 270.

- ↑ AF(M), 887 (p. 102 n3). AF(B), 896 (pp 134–135 and nn19&21).

- ↑ Rosenwein, p. 256.

- 1 2 Rosenwein, p. 257.

- ↑ Annales Fuldenses (Mainz tradition), 887 (p. 102 n3). The Annales are hereafter cited as "AF" with the post-882 tradition, Mainz or Bavarian, indicated by (M) or (B).

- ↑ MacLean, p. 70 and n116. He was usually called marchio, but once appears as dux in one charter of Charles the Fat. He was one of only three marchiones and six consiliarii who appear in the reign of Charles.

- ↑ MacLean, p. 71.

- 1 2 AF, 875 (p. 77 and n8).

- ↑ MacLean, p. 70.

- 1 2 AF(B), 883 (p. 107 and nn6&7).

- ↑ AF(M), 887 (p. 102), presents it as an invasion on Liutward's part.

- 1 2 AF(B), 886 (p. 112 and n8).

- 1 2 AF(B), 887 (p. 113 and nn3&4).

- ↑ MacLean, p. 113.

- ↑ Reuter, p. 119, suggests this, adding that Odo, Count of Paris, may have had a similar purpose in visiting Charles at Kirchen.

- ↑ MacLean, pp 167–168.

- ↑ Reuter, p. 121.

- ↑ Elliott, Gillian. "Representing Royal Authority at San Michele Maggiore in Pavia". Zeitschrift fur Kunstgeschichte 77 (2014). Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ AF(B), 888 (p. 115 and n3).

- ↑ Reuter AF, p. 115 and n3, following Liutprand of Cremona in his Antapodosis.

- 1 2 3 AF(B), 888 (p. 117 and n12).

- ↑ AF(B), 888 (p. 117 n13). Navus and sagus perhaps refer to royal rights or taxes, but more likely to as yet unidentified places. Reuter, p 122, considers Arnulf and Berengar's relationship to be one of suzerain and vassal.

- ↑ AF(B), 888 (p. 117 n14).

- ↑ AF(B), 889 (p. 119 and n2).

- ↑ AF(B), 894 (p. 128 and n12).

- 1 2 AF(B), 896 (p. 132 and nn1&2).

- ↑ AF(B), 896 (p. 134 and n19). MacLean, p. 71. The exact dates of Waltfred's rule in Friuli are unknown. Berengar was last confirmed in Friuli in 890.

- ↑ Reuter, p. 123.

- ↑ Reuter, p. 135 and nn20&21.

- ↑ Reuter, p. 135 n21.

- ↑ Reuter, p. 128, suggests the former view.

- ↑ AF(B), 900 (p. 141 and n4), with a loss of 20,000 men and many bishops. Corroborated by Liutprand, Antapodosis.

- ↑ Previté Orton, p. 337. The Gest Berengarii and Constantine Porphyrogenitus' De administrando imperio both show Berengar as declaiming responsibility for Louis's blinding.

- ↑ Previté Orton, p. 337. Rosenwein, p. 259 and n47, which recalls that some historians have accused him of neglecting its defences.

- ↑ Wickham. p. 175.

- ↑ Llewellyn, 302.

- ↑ Rosenwein, p. 277.

- ↑ Daris, pp. 228–29.

- ↑ AF(B), 889 (p. 139 and n2). Rosenwein, p. 258 and n46.

- 1 2 Rosenwein, p. 258.

- 1 2 Previté Orton, p. 336.

- ↑ Rosenwein, p. 255.

- 1 2 3 Rosenwein, p. 274 and n140.

- ↑ Previté Orton, pp 339–340, who also remarks on Berengar's "unrevengeful character."

- ↑ Rosenwein, pp 262, 274, and passim.

- ↑ Rosenwein, p. 266. The Magyars were operating, nominally at least, on Berengar's behalf.

- ↑ Rosenwein, p. 266.

- ↑ Britannica.

- ↑ Arnaldi.

- ↑ Rosenwein, p. 248.

- ↑ Rosenwein, p. 248, who calls him "a terrible warrior."

- ↑ Wickham, p. 171. This appears to be flatly contradicted, however, by the other sources. Reuter calls his a victory over Guy at the Trebbia in 888 and his campaign against Spoleto in 883 was initially successful.

- ↑ Rosenwein, p. 248 and n8.

- ↑ Rosenwein, passim.

- ↑ Rosenwein, p. 249.

Sources

- Arnaldi, Girolamo. "Berengario I, duca-marchese del Friuli, re d'Italia, imperatore" Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani 9. Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana, 1967.

- "Berengar." (2007). Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 14 May 2007.

- Daris, Joseph. Histoire du Diocèse et de la Principalité de Liège: depuis leur origine jusqu'au XIIIe siècle, Volume 1. Éditions Culture et Civilisation, 1980.

- Llewellyn, Peter. Rome in the Dark Ages. London: Faber and Faber, 1970. ISBN 0-571-08972-0.

- MacLean, Simon. Kingship and Politics in the Late Ninth Century: Charles the Fat and the end of the Carolingian Empire. Cambridge University Press: 2003.

- Previté-Orton, C. W. "Italy and Provence, 900–950." The English Historical Review, Vol. 32, No. 127. (Jul. 1917), pp 335–347.

- Reuter, Timothy (trans.) The Annals of Fulda. (Manchester Medieval series, Ninth-Century Histories, Volume II.) Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1992.

- Reuter, Timothy. Germany in the Early Middle Ages 800–1056. New York: Longman, 1991.

- Rosenwein, Barbara H. "The Family Politics of Berengar I, King of Italy (888–924)." Speculum, Vol. 71, No. 2. (Apr. 1996), pp 247–289.

- Tabacco, Giovanni. The Struggle for Power in Medieval Italy: Structures and Political Rule. (Cambridge Medieval Textbooks.) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- Wickham, Chris. Early Medieval Italy: Central Power and Local Society 400–1000. MacMillan Press: 1981.