Bertold of Regensburg (c. 1210 – 14 December 1272), also known as Berthold of Ratisbon[1] was a German preacher during the high Middle Ages.

Life

He was a native of Regensburg, and entered the Franciscan monastery there.

He was a member of the Franciscan community founded at Regensburg in 1226. His novitiate was passed under the guidance of David of Augsburg; and by 1246 he is found in a position of responsibility. By 1250 at the latest, he had begun his career as an itinerant preacher, first in Bavaria, where he endeavored to bring Duke Otto II back to obedience to the church. He then appears farther westward, at Speyer in 1254 and 1255, afterwards passing through Alsace into Switzerland. In the following years the cantons of Aargau, Thurgau, Konstanz, and Grisons, with the upper Rhine country, were the principal scenes of his activity. In 1260 he went farther afield, traversing after that date Austria, Moravia, Hungary, Silesia, Thuringia, and possibly Bohemia, reaching his Slavonic audiences through an interpreter. Some of his journeys in the East were probably in the interest of the crusade, the preaching of which was specially entrusted to him by Pope Urban IV in 1263.He died in Regensburg on 13 December 1272.

Work

The mixed character of his audiences led him to make his appeal as wide and general as possible. He avoids subtle theological questions, and advises the laity not to pry into the divine mysteries, but to leave them to the clergy, and content themselves with the credo. The weighty political occurrences of the time are also left untouched. But everything that affects the average man – his joys and his sorrows, his superstitions and his prejudices – is handled with intimate knowledge and with a careful clearness of arrangement easy for the most ignorant to follow. While exhorting all to be content with their station in life, he denounces oppressive taxes, unjust judges, usury, and dishonest trade. Jews and heretics are to be abhorred, and players who draw people's minds away to worldly pleasure; dances and tournaments are also condemned, and he has a word of blame for the women's vanity and proneness to gossip. He is never dry, always vivid and graphic, mingling with his exhortations a variety of anecdotes, jests, and the wild etymologies of the Middle Ages, making extensive use of the allegorical interpretation of the Old Testament and of his strong feeling for nature.

His German sermons, of which seventy-one have been preserved, are among the most powerful in the language, and form the chief monuments of Middle High German prose. His style is clear, direct and remarkably free from cumbrous Latin constructions; he employed, whenever he could, the pithy and homely sayings of the peasants, and is not reluctant to point his moral with a rough humour. As a thinker, he shows little sympathy with that strain of medieval mysticism which is to be observed in all the poetry of his contemporaries.[2]

Reception

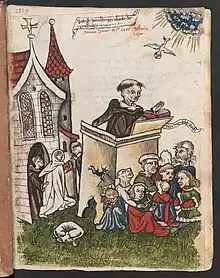

The German historians, from Berthold's contemporary, Abbot Hermann of Niederaltaich, down to the middle of the sixteenth century, speak in the most glowing terms of the force of his personality and the effect of his preaching, which is said to have attracted almost incredible numbers, so that the churches could not hold them; and he was forced to speak from a platform or a tree in the open air. The gifts of prophecy and miracles were soon attributed to him, and his fame spread from Italy to England. He must have been a preacher of great talents and success.

References

- ↑ Coulton, G. G. (1923) Life in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- ↑ Chisholm 1911.

- Attribution

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bertold von Regensburg". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 813.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Steinmeyer, E. (1908). "Berthold of Regensburg". In Jackson, Samuel Macauley (ed.). New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge. Vol. 2 (third ed.). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls. p. 71.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Steinmeyer, E. (1908). "Berthold of Regensburg". In Jackson, Samuel Macauley (ed.). New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge. Vol. 2 (third ed.). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls. p. 71.