| Beit She'arim National Park | |

|---|---|

Facade of the "Cave of the Coffins" | |

Location in Israel | |

| Location | Haifa District, Israel |

| Nearest city | Haifa |

| Coordinates | 32°42′8″N 35°7′37″E / 32.70222°N 35.12694°E |

| Governing body | Israel Nature and Parks Authority |

| Official name | Necropolis of Beit She'arim: A Landmark of Jewish Renewal |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iii |

| Designated | 2015 (39th session) |

| Reference no. | 1471 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

Beit She'arim necropolis (Hebrew: בֵּית שְׁעָרִים, "House of Gates") is an extensive necropolis of rock-cut tombs near the remains of the ancient Jewish town of Beit She'arim. In early modern times the site was the Palestinian village of Sheikh Bureik;[1] it was depopulated in the 1920s as a result of the Sursock Purchases, and identified as Beit She'arim in 1936 by historical geographer Samuel Klein.[2]

The partially excavated archaeological site known as Beit She'arim National Park consists of the rock-cut tombs and some remains of the town itself. The site is managed by the National Parks Authority. It borders the town of Kiryat Tiv'on on the northeast and is located five kilometres west of the moshav named after the historical location in 1926, a decade prior to its archaeological identification.[3] It is situated 20 km east of Haifa in the southern foothills of the Lower Galilee.

In 2015, the necropolis was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The town's vast necropolis is carved out of soft limestone and contains more than 30 burial cave systems. When the catacombs were first explored by archaeologists in the 20th-century, the tombs had already fallen into great disrepair and neglect, and the sarcophagi contained therein had almost all been broken-into by grave-robbers in search for treasure. This pillaging was believed to have happened in the 8th and 9th centuries CE based on the type of terra-cotta lamps found in situ.[4] The robbers also emptied the stone coffins of the bones of the deceased. During the Mameluk period (13th-15th centuries), the "Cave of the Coffins" (Catacomb no. 20) served as a place of refuge for Arab shepherds.[5] Lieutenant C. R. Conder of the Palestine Exploration Fund visited the site in late 1872 and described one of the systems of caves, known as "The Cave of Hell" (Mŭghâret el-Jehennum).[6] While exploring a catacomb, he found there a coin of Agrippa, which find led him to conclude that the ruins date back to "the later Jewish times, about the Christian era."[7] Benjamin Mazar, during his excavations of Sheikh Abreik, discovered coins that date no later than the time of Constantine the Great and Constantius II.[8]

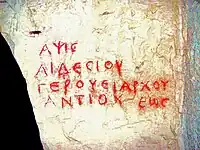

Although only a portion of the necropolis has been excavated, it has been likened to a book inscribed in stone. Its catacombs, mausoleums, and sarcophagi are adorned with elaborate symbols and figures as well as an impressive quantity of incised and painted inscriptions in Hebrew, Aramaic, Palmyrene, and Greek, documenting two centuries of historical and cultural achievement. The wealth of artistic adornments contained in this, the most ancient extensive Jewish cemetery in the world, is unparalleled anywhere.[9][10]

Name

According to Moshe Sharon, following Yechezkel Kutscher, the name of the city was Beit She'arayim or Kfar She'arayim (the House/Village of Two Gates).[1] The ancient Yemenite Jewish pronunciation of the name is also "Bet She'arayim", which is more closely related to the Ancient Greek rendition of the name, i.e. Βησάρα, "Besara".[11]

The popular orthography for the Hebrew word for house, בֵּית, is "beit", while the traditional King James one is "beth", the effort being now to replace both with the etymologically better suited "bet".

History

Iron Age

Pottery shards discovered at the site indicate that a first settlement there dates back to the Iron Age.[12]

Second Temple period

Beit She'arayim was founded at the end of the 1st century BCE, during the reign of King Herod.[13] The Roman Jewish historian Josephus Flavius, in his Vita, referred to the city in Greek as Besara, the administrative center of the estates of Queen Berenice in the Jezreel Valley.[14]

Roman and Byzantine periods

After the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, the Sanhedrin (Jewish legislature and supreme council) migrated from place to place, first going into Jabneh, then into Usha, from there into Shefar'am, and thence into Beit She'arayim.[15][14] The town is mentioned in rabbinical literature as an important center of Jewish learning during the 2nd century.[12] Rabbi Judah the Prince (Yehudah HaNasi), head of the Sanhedrin and compiler of the Mishna, lived there. In the last seventeen years of his life, he moved to Sepphoris for health reasons, but planned his burial in Beit She'arim. According to tradition, he owned there land he received as a gift from his friend, the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus. The most desired burial place for Jews was the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem, but in 135 CE, when Jews were barred from the area, Beit She'arim became an alternative.[16] The fact that Rabbi Judah was interred there led many other Jews from all over the country and from the Jewish Diaspora, from nearby Phoenicia[12] to far-away Himyar in Yemen,[17] to be buried next to his grave.

Almost 300 inscriptions primarily in Greek, but also in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Palmyrene were found on the walls of the catacombs containing numerous sarcophagi.[12]

Early Islamic period

From the beginning of the Early Islamic period (7th century), settlement was sparse.[18] Excavations uncovered 75 lamps dating to the period of Umayyad (7th-8th centuries) and Abbasid (8th–13th centuries) rule over Palestine.[12] A large Abbasid-period glassmaking facility from the 9th century was also found at the site (see below).

Crusader period

There is some evidence of activity in the nearby village area and necropolis dating to the Crusader period (12th century), probably connected to travellers and temporary settlement.[12]

Ottoman period

A small Arab village called Sheikh Bureik was located above the necropolis at least from the late 16th century.[19] A map by Pierre Jacotin from Napoleon's invasion of 1799 showed the place, named as Cheik Abrit.[20]

British Mandate

.jpg.webp)

The October 1922 census of Palestine recorded Sheikh Abreik with a population of 111 Muslims.[21] At some time during the early 1920s, the Sursuk family sold the lands of the village, including the necropolis, to the Jewish National Fund, via Yehoshua Hankin, a Zionist activist who was responsible for most of the major land purchases of the World Zionist Organization in Ottoman Palestine.[22][23] After the sale, which included lands from the Arab villages of Harithiya, Sheikh Abreik and Harbaj, a total of 59 Arab tenants were evicted from the three villages, with 3,314 pounds compensation paid.[24] In 1925 an agricultural settlement was established on the ruins of Sheikh Abreik by the Hapoel HaMizrachi, a Zionist political party and settlement movement,[25] but who later abandoned the site for a newer settlement in Sde Ya'akov.

Archaeology

History of archaeological research

The archaeological importance of the site was recognized in the 1880s by the Survey of Western Palestine, which explored many tombs and catacombs but did no excavation.[26] In 1936, Alexander Zaïd, employed by the JNF as a watchman, reported that he had found a breach in the wall of one of the caves which led into another cave decorated with inscriptions.[27] In the 1930s and 1950s, the site was excavated by Benjamin Mazar and Nahman Avigad. As late as 2014, the system of burial caves at Beit She'arim was still being explored and excavated.[28]

In 2014, the excavations at the site were resumed after a 50-year pause by Adi Erlich, on behalf of the University of Haifa's Institute of Archaeology, and are ongoing as of 2021.[29] Erlich is focusing her excavation on the actual ancient town, which occupied the hilltop above the well-studied necropolis, and of which only a few buildings had been previously discovered.[29]

Main findings

Jewish necropolis

A total of 21 catacombs have so far been discovered in the Beit She'arim necropolis, almost all containing a main hall with recesses in the wall (loculi) and sarcophagi that once contained the remains of the dead. These have since been removed, either by grave-robbers, or by Atra Kadisha, the governmental body responsible for the reburial of exhumed bones at archaeological sites. Most of the remains date from the 2nd to 4th century CE. Close to 300 sepulchral inscriptions have been discovered at the necropolis, most of which engraved in Greek uncials, and a few in Hebrew and Aramaic. Geographical references in these inscriptions reveal that the necropolis was used by people from the town of Beit She'arim, from elsewhere in Galilee, and even from further afield in the region, like Palmyra (in Syria) and Tyre.[30] Others came from Antioch (in Turkey), Mesene (South Mesopotamia, today in Iraq), the Phoenician coast (Sidon, Beirut, Byblos, all in today's Lebanon), and even Himyar (in Yemen), among other places.

Aside from an extensive body of inscriptions in several languages, the walls and tombs have many images, engraved and carved in relief, ranging from Jewish symbols and geometric decoration to animals and figures from Hellenistic myth and religion.[31] Many of the epigrams written on behalf of the deceased show a strong Hellenistic cultural influence, as many of them are taken directly from Homer's poems.[32] In one of the caves was discovered a marble slab measuring 21 × 24 × 2 cm. with the Greek inscription: Μημοριον Λέο νπου πατρος του ριββι παρηγοριου και Ιουλιανου παλατινουα ποχρυσοχων [Translation: "In memory of Leo, father of the comforting rabbi and Julian, the palatine goldsmiths"].[33] Access to many of the catacombs was obtained by passing through stone doors that once turned on their axis, and in some cases still do.

In October 2009, two new caves were opened to the public whose burial vaults date to the first two centuries CE.[34] Catacomb no. 20 and no. 14 are regularly open to the public, but most catacombs remain closed to the public, with a few being opened on weekends upon special request and prior appointment.

Cave of Yehuda HaNasi (Judah the Prince)

The Jerusalem Talmud and Babylonian Talmud cite Beit She'arim as the burial place of Rabbi Judah the Prince (Hebrew: Yehuda HaNasi).[35] His funeral is described as follows: "Miracles were wrought on that day. It was evening and all the towns gathered to mourn him, and eighteen synagogues praised him and bore him to Bet Shearim, and the daylight remained until everyone reached his home (Ketubot 12, 35a)."[36] The fact that Rabbi Judah was buried here is believed to be a major reason for the popularity of the necropolis in Late Antiquity. Catacomb no. 14 is likely to have belonged to the family of Rabbi Judah the Prince. Two tombs located next to each other within the catacomb are identified by bilingual Hebrew and Greek inscriptions as those of "R. Gamliel" and "R. Shimon", believed to refer to Judah's sons, the nasi Gamaliel III and the hakham Rabbi Shimon.[37] Another inscription refers to the tomb of "Rabbi Anania", believed to be Judah's student Hanania bar Hama.[38] According to the Talmud, Judah declared on his deathbed that "Simon [Shimon] my son shall be hakham [president of the Sanhedrin], Gamaliel my son patriarch, Hanania bar Hama shall preside over the great court".

Himyarite tombs

.jpg.webp)

In 1937, Benjamin Mazar revealed at Beit She'arim a system of tombs belonging to the Jews of Himyar (now Yemen) dating back to the 3rd century CE.[39] The strength of ties between Yemenite Jewry and the Land of Israel can be learnt by the system of tombs at Beit She'arim dating back to the 3rd century. It is of great significance that Jews from Ḥimyar were being brought for interment in what was then considered a prestigious place, near the catacombs of the Sanhedrin. Those who had the financial means brought their dead to be buried in the Land of Israel, as it was considered an outstanding virtue for Jews not to be buried in foreign lands, but rather in the land of their forefathers. It is speculated that the Ḥimyarites, during their lifetime, were known and respected in the eyes of those who dwelt in the Land of Israel, seeing that one of them, whose name was Menaḥem, was coined the epithet qyl ḥmyr [prince of Ḥimyar], in the eight-character Ḥimyari ligature, while in the Greek inscription he was called Menae presbyteros (Menaḥem, the community's elder).[40] The name of a woman written in Greek in its genitive form, Ενλογιαζ, is also engraved there, meaning either 'virtue', 'blessing', or 'gratis'; however, its precise transcription remains of scholarly dispute.[41] The people of Himyar were buried in a single catacomb, in which 40 smaller rooms or loculi branched-off from a main hall.[42]

Abbasid period

Glassmaking industry

In 1956, a bulldozer working at the site unearthed an enormous rectangular slab, 11 × 6.5 × 1.5 feet, weighing 9 tons. Initially, it was paved over, but it was eventually studied and found to be a gigantic piece of glass. A glassmaking furnace was located here in the 9th century during the Abbasid period, which produced great batches of molten glass that were cooled and later broken into small pieces for crafting glass vessels.[12][43]

Poem inside catacomb

An elegy written in Arabic script typical of the 9–10th century and containing the date AH 287 or 289 (AD 900 or 902) was found in the Magharat al-Jahannam ("Cave of Hell") catacomb during excavations conducted there in 1956. The sophisticated and beautifully worded elegy was composed by the previously unknown poet Umm al-Qasim, whose name is given in acrostic in the poem, and it can be read in Moshe Sharon's book or here on Wikipedia.[44]

Moshe Sharon speculates that this poem might be marking the beginning of the practice of treating this site as the sanctuary of Sheikh Abreik and suggests the site was used for burial at this time and possibly later as well.[1][45] He further notes that the cave within which the inscription was found forms part of a vast area of ancient ruins which constituted a natural place for the emergence of a local shrine. Drawing on the work of Tawfiq Canaan, Sharon cites his observation that 32% of the sacred sites he visited in Palestine were located in the vicinity of ancient ruins.[45]

See also

Gallery

Facade of catacomb no. 14, "Cave of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi"

Facade of catacomb no. 14, "Cave of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi" Catacomb no. 14 ("Cave of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi"), entrance door from within

Catacomb no. 14 ("Cave of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi"), entrance door from within Facade of Catacomb no. 20, the "Cave of the Coffins"

Facade of Catacomb no. 20, the "Cave of the Coffins" Stone door at entrance to Catacomb no. 20 imitating embossed wooden door

Stone door at entrance to Catacomb no. 20 imitating embossed wooden door Corridor in Catacomb no. 20, "Cave of the Coffins"

Corridor in Catacomb no. 20, "Cave of the Coffins" Sarcophagi in Catacomb no. 20

Sarcophagi in Catacomb no. 20 Chamber in Catacomb no. 20

Chamber in Catacomb no. 20 Menorah in Catacomb no. 20

Menorah in Catacomb no. 20 Catacomb no. 20

Catacomb no. 20 Chamber of burial niches

Chamber of burial niches Chamber with decorated sarcophagus (bull and eagle)

Chamber with decorated sarcophagus (bull and eagle) Sarcophagi

Sarcophagi Sarcophagus in a catacomb corridor

Sarcophagus in a catacomb corridor Sarcophagus

Sarcophagus

References

- 1 2 3 Sharon (2004), p. XXXVII

- ↑ Mazar (1957), p. 19. See also p. 137 in: Vitto, Fanny (1996). "Byzantine Mosaics at Bet She'arim: New Evidence for the History of the Site". 'Atiqot. 28: 115–146. JSTOR 23458348.. In the Jerusalem Talmud (Kila'im 9:3), the town's name is written in an elided-consonant form, (Hebrew: בית שריי), which follows more closely the Greek transliteration in Josephus' Vita § 24, (Greek: Βησάραν).

- ↑ Modern Bet She'arim Jewish Virtual Library

- ↑ Avigad (1958), p. 36.

- ↑ Avigad (1958), p. 37.

- ↑ Conder & Kitchener (1881), pp. 325 - ff.

- ↑ Conder & Kitchener (1881), p. 351.

- ↑ Mazar (1957), p. vi (Introduction).

- ↑ Eichner, Itamar (2015). "Beit She'arim declared World Heritage Site". Ynetnews.

- ↑ , UNESCO World Heritage Site,

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud, Punctuated (תלמוד בבלי מנוקד), ed. Yosef Amar, Jerusalem 1980, s.v. Sanhedrin 32b (Hebrew)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Negev & Gibson, eds. (2001)

- ↑ Mazar (1957), p. 19.

- 1 2 "Beit She'arim – The Jewish necropolis of the Roman Period". www.mfa.gov.il. Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2000. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud (Rosh Hashanah 31a–b)

- ↑ The Holy Land: An Oxford archaeological guide, From earliest times to 1700, Jerome Murphy-O'Connor

- ↑ Hirschberg (1946), pp. 53–57, 148, 283–284.

- ↑ Mazar (1957), p. 20.

- ↑ Hütteroth & Abdulfattah (1977), p. 158.

- ↑ Karmon, 1960, p. 163 Archived 2019-12-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Barron, 1923, Table XI, Sub-district of Haifa, p. 33

- ↑ Avneri, 1984, p. 122

- ↑ In 1925, according to List of villages sold by Sursocks and their partners to the Zionists since British occupation of Palestine, evidence to the Shaw Commission, 1930

- ↑ Kenneth W. Stein, The Land Question in Palestine, 1917–1939, p. 60

- ↑ Universal Jewish Encyclopedia, Vol. 6, entry "Colonies, Agricultural", p. 287.

- ↑ Survey of Western Palestine, Vol. I, pp. 325–328, 343–351

- ↑ Mazar (1957), p. 27.

- ↑ Israel Antiquities Authority, Excavators and Excavations Permit for Year 2014, Survey Permit # A-7008. This survey was conducted by Tsvika Tsuk, Yosi Bordovitz, and Achia Cohen-Tavor, on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA).

- 1 2 Official Facebook page of renewed expedition

- ↑ The Oxford encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East considers Beth She'arim of international importance (Volume 1, p. 309-11); Tessa Rajak considers its importance regional ("The rabbinic dead and the Diaspora dead at Beth She’arim" in P. Schäfer (ed.), The Talmud Yerushalmi and Graeco-Roman culture 1 (Tübingen 1997), pp. 349–66); S. Schwartz however, in Imperialism and Jewish society, 200 B.C.E. to 640 C.E. (Princeton 2001), pp. 153–8, plays down the importance of Beth She'arim.

- ↑ Beth She'arim, UNESCO World Heritage Site "tentative list", summary from 2002

- ↑ Zaharoni, M. [in Hebrew] (1978). Israel Guide - Lower Galilee and Kinneret Region (A useful encyclopedia for the knowledge of the country) (in Hebrew). Vol. 3. Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House, in affiliation with the Israel Ministry of Defence. p. 43. OCLC 745203905.

- ↑ Jewish Palestine Exploration Society, B. Maisler, 5 November 1936

- ↑ 73 Years Later, Row Erupts Over Discovery of Beit Shearim Caves, Eli Ashkenazi for Haaretz, 29 October 2009. Re-accessed 26 January 2022.

- ↑ Jerusalem Talmud (Kila'yim 9:3; Ketubot 12:3 [65b]); Babylonian Talmud (Ketubot 103b)

- ↑ Bet Shearim archaeology

- ↑ Zelcer (2002), p. 74: "In 1954 two adjoining sepulchres in cave 14 in Bet She'arim were discovered bearing the inscriptions in Hebrew and Greek "R. Gamliel" and "R. Shimon", which are believed to be the coffins of the nasi and his brother."

- ↑ The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East, Vol. 1, pp. 309–11. For a more cautious view see M. Jacobs, Die Institution des jüdischen Patriarchen, eine quellen- und traditionskritische Studie zur Geschichte der Juden in der Spätantike (Tübingen 1995), p. 247, n. 59.

- ↑ Hirschberg (1946), pp. 53–57, 148, 283–284.

- ↑ Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, 43 (2013): British Museum, London; Article by Yosef Tobi, The Jews of Yemen in light of the excavation of the Jewish synagogue in Qanī’, p. 351.

- ↑ Hirschberg (1946), pp. 56–57; p. 33 plate b. Christian Robin rejects the interpretation of the ligature qyl ḥmyr. He notes that today the inscription Menae presbyteros can no longer be seen. The only secured inscription is Ômêritôn [the Ḥimyari].

- ↑ Tobi, Yosef; Seri, Shalom, eds. (2000). Yalqut Teman - Lexicon of Yemenite Jewry (in Hebrew). עמותת אעלה בתמר. p. 37. ISBN 965-7121-03-5. p. 37.

- ↑ "The Mystery Slab of Beth She'arim". Corning Museum of Glass. Archived from the original on 2012-02-20. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ↑ Sharon (2004), p. XLI.

- 1 2 Sharon (2004), p. XLII.

Bibliography

- Avigad, N. (1958). Excavations at Beit She'arim, 1955 - Preliminary Report. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 1. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Hirschberg, Haim Zeev (1946). Yisrā’ēl ba-‘Arāb, Tel Aviv (Hebrew).

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger geographische Arbeiten. Vol. Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Mazar (Maisler), Benjamin (1957). Beth She'arim: Report on the Excavations during 1936–1940 (in Hebrew). Vol. I: Catacombs 1–4. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society. OCLC 492594574.

- Negev, Avraham; Gibson, Shimon, eds. (2001). Beth_Sharim. New York and London: Continuum. pp. 86–87. ISBN 0-8264-1316-1. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Sharon, Moshe (2004). Beth She'arayim (Beth She'arim) (Shaykh Buraik). Vol. III: D-F. Brill Publishers. pp. XXXVII–XLV. ISBN 978-90-04-13197-2.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)} - Zelcer, Heshey (2002). A Guide to the Jerusalem Talmud. Universal Publishers. ISBN 9781581126303. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

Further reading

- Mazar, Benjamin (1973) [1957]. Beth She'arim I: Catacombs 1–4. Vol. 1. Jerusalem.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Schwabe, M.; Lifshitz, B. (1974) [1967]. Beth She'arim II: The Greek Inscriptions. Vol. 2. Jerusalem.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

- The Necropolis of Beit She'arim - A Landmark of Jewish Renewal

- Bet Shearim National Park - Israel Nature and Parks Authority

- Beit She'arim National Park - official site

- Beit She-arim-The Jewish necropolis of the Roman Period, Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- Video Tour of Beit She'arim necropolis YouTube

- Jacques Neguer, The Catacombs:Conservation and reconstruction of the catacombs, Israel Antiquities Site - Conservation Department

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 5: IAA, Wikimedia commons