| Events in the |

| Life of Jesus according to the canonical gospels |

|---|

|

|

Portals: |

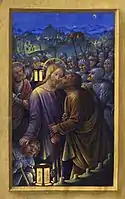

The kiss of Judas, also known as the Betrayal of Christ, is the act with which Judas identified Jesus to the multitude with swords and clubs who had come from the chief priests and elders of the people to arrest him, according to the Synoptic Gospels. The kiss is given by Judas in the Garden of Gethsemane after the Last Supper and leads directly to the arrest of Jesus by the police force of the Sanhedrin.

Within the life of Jesus in the New Testament, the events of his identification to hostile forces and subsequent execution are directly foreshadowed both when Jesus predicts his betrayal and Jesus predicts his death.

More broadly, a Judas kiss may refer to "an act appearing to be an act of friendship, which is in fact harmful to the recipient."[1]

In Christianity, the betrayal of Jesus is mourned on Spy Wednesday (Holy Wednesday) of Holy Week.[2][3]

In the New Testament

Judas was both a disciple of Jesus and one of the original twelve Apostles. Most Apostles originated from Galilee but Judas came from Judea.[4] The gospels of Matthew (26:47–50) and Mark (14:43–45) both use the Greek verb καταφιλέω, kataphileó, which means to "kiss, caress; distinct from φιλεῖν, philein; especially of an amorous kiss."[5] It is the same verb that Plutarch uses to describe a famous kiss that Alexander the Great gave to Bagoas.[6] The compound verb (κατα-) "has the force of an emphatic, ostentatious salute."[7] Lutheran theologian Johann Bengel suggests that Judas kissed him "repeatedly": "he kissed Him more than once in opposition to what he had said in the preceding verse: φιλήσω, philēsō, 'a single kiss' (Matthew 26:48), and did so as if from kindly feeling."[8]

According to Matthew 26:50, Jesus responded by saying: "Friend, do what you are here to do." Luke 22:48 quotes Jesus saying "Judas, are you betraying the Son of Man with a kiss?"[9]

Jesus's arrest follows immediately.[10]

In liturgics

In the Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom the Greek Orthodox Church uses the troparion Of thy Mystical Supper.., in which the hymnist vows to Jesus that he will "...not kiss Thee as did Judas..." (...οὐ φίλημά σοι δώσω,καθάπερ ὁ Ἰούδας...):

Τοῦ Δείπνου σου τοῦ μυστικοῦ, σήμερον, Υἱὲ Θεοῦ, κοινωνόν με παράλαβε· οὐ μὴ γὰρ τοῖς ἐχθροῖς σου τὸ Μυστήριον εἴπω· οὐ φίλημά σοι δώσω, καθάπερ ὁ Ἰούδας· ἀλλ’ ὡς ὁ Λῃστὴς ὁμολογῶ σοι· Μνήσθητί μου, Κύριε, ἐν τῇ βασιλείᾳ σου. |

Of Thy Mystic Supper receive me today, O Son of God, as a partaker; for I will not speak of the mystery to Thine enemies; I will not kiss Thee as did Judas; but as the thief, I will confess Thee: Lord, remember me in Thy kingdom.[11]: 194–195 |

Commentary

Justus Knecht comments on Judas' kiss, writing:

He did not refuse his treacherous kiss: He suffered His sacred Face to be touched by the lips of this vile traitor, and He even called him: "Friend!" "I have always treated you as My friend", He meant to imply, "why therefore do you come now at the head of My enemies, and betray Me to them by a kiss!" This loving treatment on the part of our Lord was to the ungrateful traitor a last hour of grace. Jesus gave him to understand that He still loved him in spite of his vile crime, and was ready to forgive him.[12]

Cornelius a Lapide in his Great commentary writes,

Victor of Antioch says, "The unhappy man gave the kiss of peace to Him against whom he was laying deadly snares." "Giving," says pseudo-Jerome, "the sign of the kiss with the poison of deceit." Moreover, though Christ felt deeply, and was much pained at His betrayal by Judas, yet He refused not his kiss, and gave him a loving kiss in return. 1. "That He might not seem to shrink from treachery" (St. Ambrose in Luke xxi. 45), but willingly to embrace it and even greater indignities, for our sake. 2. To soften and pierce the heart of Judas; and 3. To teach us to love our enemies and those whom we know would rage against us (St. Hilary of Poitiers). For Christ hated not, but loved the traitor, and grieved more at his sin than at His own betrayal, and accordingly strove to lead him to repentance.[13]

In art

The scene is nearly always included, either as the Kiss itself, or the moment after, the Arrest of Jesus, or the two combined (as above), in the cycles of the Life of Christ in art or Passion of Jesus in various media. In some Byzantine cycles it is the only scene before the Crucifixion.[14] A few examples include:

- Probably the best known is from Giotto's cycle in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua

- The Taking of Christ by Caravaggio[15]

- A sixth-century Byzantine mosaic in Ravenna

- A fresco by Barna da Siena

- A sculpture representing the Kiss of Judas appears on the Passion façade of the Sagrada Família basilica in Barcelona

- The kiss of Judas in art

Fresco by Fra Angelico, San Marco, Florence, 1437–1446

Fresco by Fra Angelico, San Marco, Florence, 1437–1446 Judas betraying Jesus with a kiss, in the Grandes Heures of Anne of Brittany, between 1503 and 1508

Judas betraying Jesus with a kiss, in the Grandes Heures of Anne of Brittany, between 1503 and 1508.jpg.webp) The Taking of Christ by Caravaggio, 1602

The Taking of Christ by Caravaggio, 1602 Wilhelm Marstrand, Kiss of Judas, undated (between 1830 and 1873)

Wilhelm Marstrand, Kiss of Judas, undated (between 1830 and 1873) Study for The Judas Kiss by Gustave Doré, 1865

Study for The Judas Kiss by Gustave Doré, 1865_-_James_Tissot.jpg.webp) The Kiss of Judas by James Tissot, Brooklyn Museum, between 1886 and 1894

The Kiss of Judas by James Tissot, Brooklyn Museum, between 1886 and 1894

See also

References

- ↑ "Judas kiss". TheFreeDictionary.com.

- ↑ Cooper, J.HB. (23 October 2013). Dictionary of Christianity. Routledge. p. 124. ISBN 9781134265466.

Holy Week. The last week in LENT. It begins on PALM SUNDAY; the fourth day is called SPY WEDNESDAY; the fifth is MAUNDY THURSDAY or HOLY THURSDAY; the sixth is GOOD FRIDAY; and the last 'Holy Saturday', or the 'Great Sabbath'.

- ↑ Brewer, Ebenezer Cobham (1896). The Historic Notebook: With an Appendix of Battles. J. B. Lippincott. p. 669.

The last seven days of this period constitute Holy Week. The first day of Holy Week is Palm Sunday, the fourth day is Spy Wednesday, the fifth Maundy Thursday or Holy Thursday, the sixth Good Friday or Holy Friday, and the last Holy Saturday or the Great Sabbath in Eastern Rite traditions.

- ↑ Judd Jr., Frank (2006). "Judas in the New Testament, the Restoration, and the Gospel of Judas". Brigham Young University Studies. 45 (2): 35–43. JSTOR 43044515 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ καταφιλέω. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- ↑ Plutarch (1919). "67.4". Alexander. Translated by Bernadotte Perrin.

λέγεται δὲ μεθύοντα αὐτὸν θεωρεῖν ἀγῶνας χορῶν, τὸν δὲ ἐρώμενον Βαγώαν χορεύοντα νικῆσαι καὶ κεκοσμημένον διὰ τοῦ θεάτρου παρελθόντα καθίσαι παρ᾽ αὐτόν: ἰδόντας δὲ τοὺς Μακεδόνας κροτεῖν καὶ βοᾶν φιλῆσαι κελεύοντας, ἄχρι οὗ περιβαλὼν κατεφίλησεν

- ↑ Vincent's Word Studies on Matthew 26, accessed 27 February 2017

- ↑ Bengel's Gnomon on Matthew 26, accessed 27 February 2017

- ↑ Dear, John. "On Holy Thursday, betrayal and friendship", National Catholic Reporter, March 27, 2012

- ↑ Matthew 26:50

- ↑ Rev. Nicholas M. Elias (1966). The Divine Liturgy Explained (4 ed.). Athens: Papadimitriou Publishing Co. (published 2000).

- ↑ Knecht, Friedrich Justus (1910). . A Practical Commentary on Holy Scripture. B. Herder.

- ↑ Lapide, Cornelius (1889). The great commentary of Cornelius à Lapide. Translated by Thomas Wimberly Mossman.

- ↑ Schiller, Gertrud, Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. II, p. 52, 1972 (English trans from German), Lund Humphries, London, ISBN 0853313245

- ↑ For a discussion of the kiss of Judas with respect to Caravaggio's The Taking of Christ (now in the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin), together with a summary of traditional ecclesiastical interpretation of that gesture, see Franco Mormando, "Just as your lips approach the lips of your brothers: Judas Iscariot and the Kiss of Betrayal" in Saints and Sinners: Caravaggio and the Baroque Image, ed. F. Mormando, Chestnut Hill, MA: The McMullen Museum of Art of Boston College, 1999, 179–90.

Further reading

- Grubb, Nancy (1996). The Life of Christ. New York City: Abbeville Publishing Group. ISBN 0-7892-0144-5. OCLC 34412342.

Media related to Kiss of Judas Iscariot at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Kiss of Judas Iscariot at Wikimedia Commons