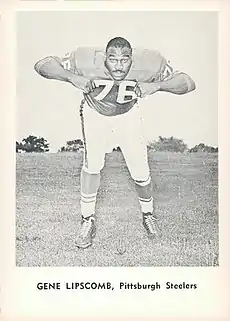

Lipscomb c. 1961 | |||||

| No. 85, 78, 76 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position: | Defensive tackle | ||||

| Personal information | |||||

| Born: | August 9, 1931 Uniontown, Alabama, U.S. | ||||

| Died: | May 10, 1963 (aged 31) Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. | ||||

| Height: | 6 ft 6 in (1.98 m) | ||||

| Weight: | 306 lb (139 kg) | ||||

| Career information | |||||

| High school: | Miller (Detroit, Michigan) | ||||

| College: | None | ||||

| Undrafted: | 1953 | ||||

| Career history | |||||

| Career highlights and awards | |||||

| |||||

| Career NFL statistics | |||||

| |||||

| Player stats at NFL.com · PFR | |||||

Eugene Allen Lipscomb (August 9, 1931 – May 10, 1963) was an American professional football defensive tackle in the National Football League (NFL) for ten seasons and a professional wrestler. He was known by the nickname "Big Daddy", owing to his habit of calling everyone around him "Little Daddy".[1][2]

Early life

Born in Uniontown, Alabama in a family of cotton pickers, Lipscomb never knew his father, as he died in a federal Civilian Conservation Corps camp from illness. His mother moved her only son with her to Detroit, Michigan at age three. When he was 11, his mother was stabbed to death on the street. He carried the homicide photos with him in his playing career. He then lived with his maternal grandparents, where he had to pay for his own clothes and room. He worked a variety of jobs as a youth while attending school, which included washing dishes, truck loading, junkyard work and also at a steel mill. He was subject to abuse by his grandfather, who once tied him to the bed to whip him when he stole a bottle of whiskey. He played basketball and football at Sidney D. Miller Middle School but he was ruled ineligible in his senior year to being discovered playing semipro ball. His football coach Will Robinson recommended that Lipscomb should enlist in the Marine Corps, which he did.

Professional career

After graduating from Miller High School, Lipscomb did not attend college and instead served in the United States Marine Corps, where he was stationed at Camp Pendleton and played on the camp's football team. His talent drew the eye of Pete Rozelle, who was working with the Los Angeles Rams in public relations. He gave a recommendation to head scout Eddie Kotal, who also liked what he saw.

Lipscomb was signed as an undrafted free agent by the Los Angeles Rams in 1953. After playing a few games at defensive end, he was moved to defensive tackle the following year.[3] He was waived in September 1956 and claimed by the Baltimore Colts.[4] In 1957, he led the team in tackles with 137. In 1958 and 1959, he was named to the Pro Bowl and was instrumental in the Colts' two consecutive NFL championships. He made up a defensive line that included two future Hall of Famers in Gino Marchetti and Art Donovan to go with Don Joyce and Ordell Braase. Lipscomb favored targeting from sideline to sideline. When asked about interior lineman plays he stated, "If a player starts holding, I smack my hand flat against the earhole of his helmet. When he complains about dirty playing, I tell him to stop holding and I'll stop slapping. That's what I call working out a problem."

In July 1961, Lipscomb was traded to the Pittsburgh Steelers with center Buzz Nutter for receiver Jimmy Orr, defensive tackle Joe Lewis and linebacker Dick Campbell.[5][6][7] He was encouraged to play more up the field to wreak havoc on guards. The result was a first season that saw a total of 17.5 sacks (as according to retroactive counting of statistics). He was described by teammate Dick Hoak as "the first really big guy, at least that I ever saw, who was really fast and quick. Big Daddy and I came on the team together so we had a common friendship. He was the first to go sideline to sideline. Other big guys couldn't do that."[8]

Lipscomb's final NFL game was the Pro Bowl in January 1963, in which he was voted lineman of the game.[9][10] During the 1959–60 and 1960–61 off-seasons, he was a professional wrestler.[11]

The Professional Football Researchers Association named Lipscomb to the PFRA Hall of Very Good Class of 2006.[12]

In 2019, Lipscomb was selected as a finalist for the NFL's 100th Anniversary Team.[13] Despite his accomplishments, he has never been a candidate for the senior ballot of the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Personal life

Lipscomb had a taste for both women and alcohol, which resulted in three marriages and divorces, with one case of bigamy; he had two children with his second wife.[14] He was also known as a "gentle giant" that on more than one occasion would arrange to give shoes to underprivileged children who he saw did not have any on the street.[15]

Death

On May 10, 1963, Lipscomb went out on the streets of Baltimore, Maryland. According to his companion of that night in Tim Black, they partied with women until 3am before trying heroin. Black stated that Lipscomb had been using it multiple times a week for the last six months, with Black being his dealer. When Lipscomb tried the heroin, he began drooling according to Black, and it was only after failing to awaken him that he took him to a hospital. The autospy revealed that Libscomb died of an overdose of heroin with fresh needle marks along with a fatty liver.[1][16][2][17][18] He was pronounced dead just before 8am at Lutheran Hospital.

Friends of Lipscomb could not believe it happened to him due to his professed fear of needles, with some believing that he was the victim of a homicide for robbery. Before his body was moved for burial, thousands went to his viewing in Baltimore, reportedly stretching multiple city blocks even when it was set to close at 10pm.[19] His funeral was held in Detroit to a crowd of over a thousand people composed of teammates and loved ones. He was buried at Lincoln Park Memorial Cemetery.[20]

Further reading

- Davis, Kelcie "Gene Lipscomb 1931-1963", Blackpast Sports Bio, November 18, 2019

References

- 1 2 "Grid star Lipscomb dies, narcotics use suspected". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. May 11, 1963. p. 1.

- 1 2 "Lipscomb dies under mysterious circumstances". Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). Associated Press. May 10, 1963. p. 2B.

- ↑ "State Your Case: Hall Voters Should Give 'Big Daddy' Another Chance". 24 October 2023.

- ↑ "Colts list biggest tan contingent; await Skins". Baltimore Afro-American. (Maryland). September 15, 1956. p. 22.

- ↑ "Lipscomb to join Steelers in 3-2 deal involving Orr". Pittsburgh Press. July 19, 1961. p. 38.

- ↑ Miller, Jimmy (July 20, 1961). "Steelers trade Orr, Lewis and Campbell". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. 27.

- ↑ "Ewbank stresses youth movement for Colts". Reading Eagle. (Pennsylvania). Associated Press. July 20, 1961. p. 18.

- ↑ "Remembering Steelers Big Daddy Lipscomb: From Hero to Heroin". 9 March 2009.

- ↑ "East stars score 30-20 upset in Pro Bowl". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. January 14, 1963. p. 22.

- ↑ "Jim Brown helps Sherman defeat Lombardi". Reading Eagle. (Pennsylvania). UPI. January 14, 1963. p. 14.

- ↑ https://www.wrestlingdata.com/index.php?befehl=bios&wrestler=13853.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ "Hall of Very Good Class of 2006". Archived from the original on January 18, 2017. Retrieved November 23, 2016.

- ↑ "Defensive lineman finalists revealed for NFL 100 All-Time Team". NFL.com.

- ↑ "From the PG Archives".

- ↑ "The Ballad of Big Daddy".

- ↑ "Steeler star Lipscomb dies, dope hinted". Pittsburgh Press. May 10, 1963. p. 1.

- ↑ "Heroin caused Lipscomb death". Pittsburgh Press. UPI. May 15, 1963. p. 1.

- ↑ "New law may result in freedom". Baltimore Afro-American. (Maryland). July 27, 1963. p. 1.

- ↑ "Steeler Nation: Pittsburgh Steelers News, Rumors, & More".

- ↑ "Final respects paid Lipscomb". Pittsburgh Press. UPI. May 16, 1963. p. 46.

External links

- Michigan Sports Hall of Fame – Eugene Allen (Gene) Lipscomb

- Steeler Nation – Eugene “Big Daddy” Lipscomb

- Gene Lipscomb at Find a Grave