Biracial and multiracial identity development is described as a process across the life span that is based on internal and external forces such as individual family structure, cultural knowledge, physical appearance, geographic location, peer culture, opportunities for exploration, socio-historical context, etc.[1]

Biracial identity development includes self-identification. A multiracial or biracial person is someone whose parents or ancestors are from different racial backgrounds. Over time many terms have been used to describe those that have a multiracial background. Some of the terms used in the past are considered insulting and offensive (mutt, mongrel, half breed); these terms were given because a person was not recognized by one specific race.

While multiracial identity development refers to the process of identity development of individuals who self-identify with multiple racial groups,[1] multiracial individuals are defined as those whose parents are of two or more distinct racial groups.[2]

Background

Racial identity development defines an individual's attitudes about self-identity, and directly affects the individual's attitudes about other individuals both within their racial group(s) and others. Racial identity development often requires individuals to interact with concepts of inequality and racism that shape racial understandings in the US.

Research on biracial and multiracial identity development has been influenced by previous research on race. Most of this initial research is focused on black racial identity development (Cross, 1971)[3] and minority identity development (Morten and Atkinson, 1983)[4].

Like other identities, mixed race people have not been easily accepted in the United States. Numerous laws and practices prohibited interracial sex, marriage, and therefore, mixed race children. Below are some landmark moments in mixed race history.

Miscegenation laws

Anti-miscegenation laws or miscegenation laws enforced racial segregation through marriage and intimate relationships by criminalizing interracial marriage. Certain communities also prohibit having sexual intercourse with a person of another race. As a result of the Supreme Court case Loving v. Virginia, these laws have since been changed in all U.S. states - interracial marriage is permitted. The last states to change these laws were South Carolina and Alabama. South Carolina made this change in 1998[5] and in 2000, Alabama became the last state in the United States to legalize interracial marriage.[6]

Biracial and multiracial categorization

"One Drop Rule"

The one-drop rule is a historical social and legal principle of racial classification in the United States. The one drop rule asserts that any person with one ancestor of African ancestry is considered to be Black. This idea was influenced by the concept of "white purity" and concerns of those "tainted" with black ancestry passing as white in the U.S's deeply segregated south.[7] In this time, classification as Black rather than mulatto or mixed became prevalent. The "One Drop Rule" was used as a way to make people of color, especially multiracial Americans feel even more inferior and confused and was put into effect in the 1920s. No other country in the world at the time had thought of or implemented such a discriminatory and specific rule on its citizens[8] The One Drop Rule in a way was taking the Jim Crow Law to a new extreme level to make sure it stayed in power and was used as another extreme measure of social classification. Eventually, biracial and multiracial individuals challenged this assumption and created a new perspective of biracial identity and included the "biracial" option on the census.[9]

Hypodescent

The concept of hypodescent refers to the automatic assignment of children of a mixed union between different socioeconomic or ethnic groups to the group with the lower status. This is especially prevalent in the United States where the "one drop rule is still upheld as Whites were a historically dominant social group. People of mixed race ancestry would be categorized as the nonwhite race using this concept.[10] Even in mixed race offspring with no white parent, the racist "one drop rule" places the nonblack racial group as dominant so that the offspring is socially considered black.

Phenotype

A way of classifying someone by looking at their physical appearances, like facial features, skull shape, hair texture etc. and choosing their race based on what they look like.

The U.S. Census

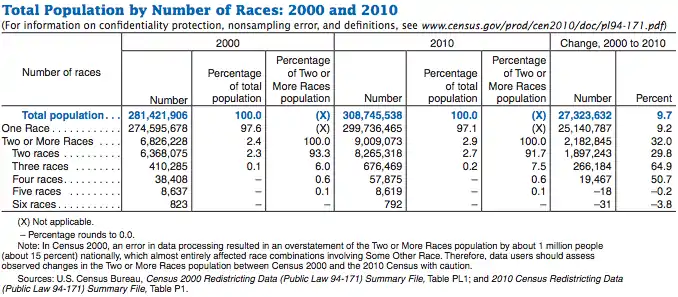

Before 2000 United States Census respondents were only able to select one race when submitting census data. This means that the census contained no statistical information regarding particular racial mixes and their frequency in the U.S. before this time.

Demographics

The population of biracial and multiracial people in the U.S. is growing. A comparison of data from the 2000 and 2010 United States Census indicates an overall population increase in individuals identifying with two or more races from 6.8 million people to 9 million people (US Census Data, 2010).[11] In examining specific race combinations, the data showed that, "people who reported White as well as Black or African American—a population that grew by over one million people, increasing by 134 percent—and people who reported White as well as Asian—a population that grew by about three-quarters of a million people, increasing by 87 percent" (US Census Data, 2010). In 2004, one in 40 persons in the United States self-identified as a multiracial, and by the year 2050, it is projected that as many as one in five Americans will claim a Multiracial background, and in turn, a Multiracial or Biracial identity (Lee & Bean, 2004).[12]

Early theories

When initial racial identity development research is applied to biracial and multiracial people, there are limitations, as they fail to recognize variance in developmental experiences that occur within racial groups (Gibbs, 1987).[13] This research assumes that individuals would choose to identify with, or choose to reject, one racial group over another dependent on life stage. Also, initial racial identity development research does not address real-life resolutions for people upholding multiple racial group identities (Poston, 1990).[14] These assumptions display the need for biracial and multiracial identity development that focuses on the unique aspects of the experience of biracial and multiracial identity development. These theories can be categorized under the following approaches: problem, equivalent, variant, and ecological.

Problem Approach

This approach predicts negative outcomes of having multiracial identity. Originating from the Jim Crow era, this theoretical angle focuses on the deficits and problems that are a result of multiracial identities, concluding multiracial individuals are more often victims of rejection, isolation, stigmatization even from both the identities they represent.[15] As a result, multiracial individuals often deal with negative outcomes such as an inferiority complex, hypersensitivity, and moodiness due to their experiences with society.

Stonequist's Marginal Person Model

American sociologist, Everett Stonequist was the first to publish research about the identity development of biracial individuals. His book, The Marginal Man: A Study in Personality and Culture Conflict (1937) discusses pathology in Black families through comparison of Black minority samples to White majority samples. Stonequist claimed that developing a biracial identity is a marginal experience, in which biracial people belong in two worlds and none all at the same time.[16] That they experience uncertainty and ambiguity, which can worsen problems people face identifying with their own racial groups and others (Gibbs, 1987).[13] Building upon the "marginal man", Stonequist (1937) explained that multiracial individuals have a heightened awareness and adaptability to both sides of racial conflict between African Americans and caucasians.[15] As a result, there is an internal crisis within the multiracial individual due to the cultural conflicts that surround them. This internal conflict can be seen in the form of "confusion, shock, disillusionment, and estrangement".[15] A primary limitation of this model is that it is largely internal and focused on development within biracial individuals. The model does not discuss factors such as racism or racial hierarchy, which can worsen feelings of marginality for biracial persons. It does not address other functions of marginality that could also affect biracial identity development such as conflict between parental racial groups, or absence of influence from one racial identity (Hall, 2001).[17] The model fails to describe the experience of biracial people that exhibit characteristics of both races without conflict or feelings of marginality (Poston, 1990).[14]

Modern theories

To address the limitations of Stonequist's Marginal Person Model, researchers have expanded biracial identity development research based on relevant and current understandings of biracial people. Most concepts of biracial identity development highlight the need for racial identity development across the lifespan. This type of development recognizes that identity is no more static a cultural entity than any other and that this fluidity of identity is shaped by the individual's social circumstances and capital (Hall, 2001).[17]

Equivalent Approach

The equivalent approach presents a positive angle towards multiracial identity development, explaining racial identity cultivation is equivalent between monoracial and multiracial individuals yet yields different outcomes. Stemming from the civil rights movement in the U.S. in the 1960s, this approach reorganizes what it means to be "black", encouraging mixed race people to develop a positive integration and eventual adoption of their black identity. Any negative outcomes of this process were considered to be internalized racism of their blackness from microaggressions.[15] This theory soon proved inadequate for explaining mixed identity development, as it did not allow the identification of multiple ethnic groups nor recognize their struggles of developing racial identities.[18][19] The equivalent approach was derived from Erikson's (1968) ego-identity formation model, which explains a stable identity is formed through a process of "exploratory and experimental stages" that eventually result in a racial identity.[15]

Poston's Biracial Identity Development Model

Walker S. Carlos Poston challenged Stonequist's Marginal Man theory and claimed that existing models of minority identity development did not reflect the experiences of biracial and multiracial individuals.[20] Poston proposed the first model for the development of a healthy biracial and multiracial identity in 1990.[1] This model was developed from research on biracial individuals and information from relevant support groups. Rooted in counseling psychology, the model adapts Cross’ (1987)[21] concept of reference group orientation (RGO), which includes constructions of racial identity, esteem, and ideology. Poston's model divided the biracial and multiracial identity development process into five distinct stages:

- Personal Identity: young children's sense of self and personal identity is not linked to a racial or ethnic group.[20]

- Choice of Group Characterization:[1] an individual chooses a multicultural identity that includes both parents’ heritage groups or one parent's racial heritage. This stage is based on personal factors (such as physical appearance and cultural knowledge) and environmental factors (such as perceived group status and social support).[20]

- Enmeshment/Denial: confusion and guilt over not being able to identify with all aspects of one's heritage can lead to feelings of "anger, shame, and self-hatred". Resolving this guilt is necessary in order to move past this stage.[20]

- Appreciation: broadening of one's racial group membership and knowledge about multiethnic heritage,[1] even though individuals may choose to identify with one group more than others.[20]

- Integration: recognition and appreciation of all racial and ethnic identities that make an individual unique.[1]

This model offers an alternative identity development process compared to the minority identity development models widely used in the student affairs profession.[20] However, it does not accurately address how societal racism affects the development process of people of color[20] and suggests that there is only one healthy identity outcome for biracial and multiracial individuals.[1]

Variant Approach

The variant approach is one of the most contemporary racial development theories, explaining racial identity cultivation is a process that takes place over a series of stages according to age.[15] Starting in the 1980s, new researchers sought to explain that mixed-race individuals comprised their own racial category, establishing an independent "multiracial identity". Among these researchers, Maria Root published Racially Mixed People in America (1992) which justified mixed race individuals as their own racial category, thus explaining they endure their own unique racial development.[15] The variant approach challenges previous theoretical approaches lack integration of multical racial identities.[15] The progression of this theory is represented by the following chronological stages: personal identity, choice of group categorization, denial, appreciation of group orientation, and integration.[18]

Root's Resolutions for Resolving Otherness

Maria Root's Resolutions for Resolving Otherness (1990)[22] address the phenomenological experience of otherness in a biracial context and introduced a new identity group: multiracial.[20] With a footing in cultural psychology, Root suggests that the strongest conflict in biracial and multiracial identity development is the tension between racial components within one's self. She presents alternative resolutions for resolving ethnic identity based on research covering the racial hierarchy and history of the U.S., and the roles of family, age, or gender in the individual's development.

Root's resolutions reflect a fluidity of identity formation; rejecting the linear progression of stages followed by Poston.[1] They include assessment of socio-cultural, political, and familial influences on biracial identity development. The four resolutions that biracial and multiracial individuals can use to positively cope with “otherness” are as follows:[20]

- Acceptance of the identity society assigns: an individual identifies with the group that others assume they belong to the most. This is often determined by one's family ties and personal allegiance to the racial group (typically the minority group) that others assign.[20]

- Identification with both racial groups: an individual may be able to identify with both (or all) heritage groups. This is largely affected by societal support and one's ability to remain resistance to other's influences.[20]

- Identification with a single racial group: an individual chooses one racial group independently of external forces.

- Identification as a new racial group: an individual may choose to move fluidly throughout racial groups, but overall identifies with other biracial or multiracial people.[20]

Root's theory suggests that mixed race individuals "might self-identify in more than one way at the same time or move fluidity among a number of identities,".[20] These alternatives for resolving otherness are not mutually exclusive; no one resolution is better than another. As explained by Garbarini-Phillippe (2010), “any outcome or combination of outcomes reflect a healthy and positive development of mixed-race identity,”.[1] On the contrary, biracial adolescents who identify as part White may seem integrated but actually may not identify with any social group. Tokenism and dating are common issues for biracial adolescents and their identity. Tokenism is a practice that spotlights an individual to be the minority representative.[23]

Kich's Conceptualization of Biracial Identity Development

Miville, Constantine, Baysden and So-Lloyd (2005) discussed the following three-stage and six-stage models that biracial individuals experience. Kich's Conceptualization of Biracial Identity Development (1992) focuses on the transition from straying away from the pressures of monoracial self-identity to a stronger desire of biracial self-identity as one's age progresses. Kich's model is divided into three stages during biracial development:[24]

- Stage 1 (3–10 years old): How one's own feelings and what external feelings are differs.[24]

- Stage 2 (8 years old-young adulthood): Challenges revolve around feeling accepted by oneself and by others.[24]

- Stage 3 (Late adolescence/young adulthood): Completely integrates a biracial and bicultural identity.[24]

Kerwin and Ponterotto's Model of Biracial Identity Development

Kerwin and Ponterotto's Model of Biracial Identity Development (1995) addresses awareness in racial identity through developmental stages based on age. This model recognizes that racial identity varies between public and private environments and is altered by different factors. Kerwin and Ponterotto state that exclusion may not only be experienced by White individuals, but also individuals of color (Miville, Constantine, Baysden & So-Lloyd, 2005).[24]

- Preschool (0–5 years old): Begins to observe differences and similarities in how they look. Levels of eagerness to discuss issues in regard to race amongst parents are apparent.[24]

- Entry to School: As involvements increase with certain groups, they are influenced with the idea of identifying with a monoracial label.[24]

- Preadolescence: Becomes more cognizant of how social groups are represented by certain characteristics such as skin tone, religion and ethnicity. Sensitivity to race differs depending on certain environmental factors such as being immersed in a monocultural or diverse context.[24]

- Adolescence: Feelings of pressure heighten to identify with the racial group that is associated with the parent of color.[24]

- College/Young Adulthood: Continues to engage in a monoracial group and subtly realizes situations involved race-related remarks.[24]

- Adulthood: Ongoing discovery on culture and race, determining self-perceptions of different identities and has stronger resilience for diversified cultural contexts.[24]

Ecological Approach

The most recent of all racial identity development theoretical approaches, the ecological approach allows an individual to deny any part of their multiracial identity. In this theory, the following assumptions are made: multiracial individuals extract their racial identity based on their personal contextual environment, there are no consistent stages of racial identity development, and that privileging multiracial identity only extends the flaws of identity theory and does not offer tangible solutions.[15]

Renn's Ecological Theory of Mixed Race Identity Development

Dr. Kristen A. Renn was the first to look at multiracial identity development from an ecological lens.[20] Renn used Urie Bronfenbrenner's Person, Process, Context, Time (PPCT) model to determine which ecological factors were most influential on biracial and multiracial identity development.[25] Three dominant ecological factors emerged from Renn's research: physical appearance, cultural knowledge, and peer culture.

Physical appearance is the most influential factor and is described as how a biracial and multiracial person looks (i.e.: skin tone, hair texture, hair color, eye and nose shape, etc.). Cultural Knowledge is the second most important factor and can include the history that a multiracial individual knows about their various heritage groups, languages spoken, etc. Peer culture, the third most influential factor, can be described as support, acceptance, and/or resistance from peer groups. For example, racism among White students is an aspect of college peer culture that can impact an individual's perception of themself.

Renn conducted several qualitative studies across higher education institutions in the eastern and midwestern United States in 2000 and 2004. From the analysis of written responses, observations, focus groups, and archival sources, Renn identified five non-exclusive patterns of identity among multiracial college students.[20] The five identity patterns recognized by Renn include the following:

- Monoracial Identity: An individual identifies with one of the racial categories that makes up their heritage background. Forty-eight percent of Renn's (2004) participants identified as having a monoracial identity.[25]

- Multiple Monoracial Identities: An individual identifies with two or more racial categories that make up their heritage background. Within a given time and place, both personal and contextual factors influence how an individual chooses to identify. Forty-eight percent of the participants also self-identified with this identity pattern.[20]

- Multiracial Identity: An individual identifies as part of a “multiracial” or “mixed” racial category, instead of identifying with one racial or other racial categories. According to Renn (2008), over eighty-nine percent of students from her 2004 study identified as part of a multiracial group.[20]

- Extraracial Identity: An individual chooses to “opt out” of racial categorization or not to identify with one of the racial categories presented in the U.S. Census. One-fourth of the students that Renn (2004) interviewed identified with this category, and saw race as a social construct with no biological roots.[20]

- Situational Identity: An individual identifies differently depending on the situation or context, reinforcing the notion that racial identity is both fluid and contextual. Sixty-one percent of Renn's (2004) participants identified in different ways depending on varying contexts.[25]

Like Root's resolutions, Renn's theory accounted for the fluidity of identity development. Each of the stages represented above are non-linear. Renn explained that some students from her studies self-identified with more than one identity pattern. This is why the total percentage of these identity patterns are more than 100 percent.[20] For example, a participant of European and African-American descent may have identified as multiracial initially, but also as Monoracial or Multiple Monoracial depending on the context of their environment or interactions with other individuals. An ecological approach also suggests that entitling any racial identity over another regardless of being multiracial, racial or monoracial will repeat the issues of other identity models (Mawhinney & Petchauer, 2013).[26]

Commonalities of Racial Identity Development Theories

The commonalities of these theories characterize mutli-racial identity development as marked struggle especially in early development. Most approaches reserve the ages between 3–10 years old to having confusion and outside confrontation that continue well even to adult years of a biracial individual. Some of these struggles include inconsistent identification within both private and public spaces, justifying identity choices, pressure to identify with one race, lack of role models, conflicting messages, and double rejection from both dominant and minority racial groups.[27] These hardships are various and ultimately impact maturity and adjustment to society depending on the environment in which the child is raised and the interactions they had.[28]

Situational Identity/ Race Switching

For many multiracial individuals, there is a lot of bouncing around between racial categories. Hitlin, Brown, and Elder Jr. (2006) studies concluded that people who identified as biracial are more likely to change how they identify than people who identified with one race their whole life. Biracial people seem to be very fluid in how they identify, but there are certain factors that make it more likely for them to identify a certain way. People who grew up with a higher social and economic status were less likely to race switch than someone who grew up in a lower status. Being around a racially charged environment can also drastically alter how much a multi-racial individual race switches. Sanchez, Shih & Garcia (2009) concluded in a study that people who were more fluid with their racial identification had worse mental health, not necessarily due to their own identity crisis but due to outsiders pressure to classify the individual. This can cause lots of stress and frustration for the multiracial individual affecting their mental health.[29]

Racial Discrimination and Psychological Adjustment

Racial Discrimination

Racial Discrimination has affected the mental health of many multiracial individuals. Coleman and Carter (2007) concluded biracial people particularly, Black/White college students felt the need to identify as one race. A similar study done, Townsend, Markus, and Bergsieker (2009) saw that multiracial college students who were indicated to pick just one race on demographic questions ended up having less motivation and less self-esteem in comparison with other students who were allowed to choose more than one race. Since in these studies there were small study groups, the evidence does show discrimination can affect the mental health of multiracial individuals.[29]

Psychological Adjustment

Many incidents of multiracial people being affected by the pressure to align with one race have been recorded. Simple things like microaggressions, physical and verbal abuse about the minority race in them come at many multiracial individuals. This then causes them to just force themselves to align with a certain race to stop the abuse.[29] However, multiracial individuals who are able to identify themselves accurately during their adolescent development have higher levels of efficacy, self-esteem and lower stereotype vulnerability. A study with 3,282 students from three high schools looked at the correlation between ethnic and racial identity and self-esteem levels (Bracey, Bámaca & Umaña, 2004).[30] Students reported their parents’ racial categories to determine classification of racial group membership, which included a variety of monoracial and biracial identities. Findings suggest that there is a positive correlation between self-esteem and ethnic identity. Although Biracial participants did not show higher self-esteem than Black participants, they did show higher self-esteem than Asian participants. Studies show that although Biracial adolescents display less resilience to racism and have a smaller community support than Black adolescents, being bicultural introduces “a broader base of social support, more positive attitudes toward both cultures, and a strong sense of personal identity and efficacy,” which results in high self-esteem (LaFromboise, Coleman & Gerton, 1993). LaFromboise, Coleman and Gerton use bicultural efficacy to describe an individual's confidence in his/her capability to live within two cultural groups sufficiently without altering his/her own self-identification (1993).[31]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Garbarini-Philippe, Roberta (2010). "Perceptions, Representation, and Identity Development of Multiracial Students in American Higher Education" (PDF). Journal of Student Affairs at New York University. 6: 1–6.

- ↑ Viager, Ashley (2011). "Multiracial Identity Development: Understanding Choice of Racial Identity in Asian-White College Students" (PDF). Journal of the Indiana University Student Personnel Association: 38–45.

- ↑ Cross, W.E. (1971). "The Negro-toBlack conversion experience: Toward a psychology of Black liberation". Black World. 20: 13–27.

- ↑ Morten, G; Atkinson, D.R. (1983). "Minority identity development and preference for counselor race". Journal of Negro Education (52 ed.). 52 (2): 156–161. doi:10.2307/2295032. JSTOR 2295032.

- ↑ "A Groundbreaking Interracial Marriage". ABC News. 8 January 2009. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ↑ "Alabama Interracial Marriage, Amendment 2 (2000) - Ballotpedia". ballotpedia.org. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ↑ "Mixed Race America - Who Is Black? One Nation's Definition | Jefferson's Blood | FRONTLINE | PBS". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ↑ Freeman, Harold P. (1 March 2003). "Commentary on the Meaning of Race in Science and Society". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 12 (3): 232s–236s. ISSN 1055-9965. PMID 12646516.

- ↑ Hud-Aleem, Raushanah; Countryman, Jacqueline (November 2008). "Biracial Identity Development and Recommendations in Therapy". Psychiatry (Edgmont). 5 (11): 37–44. ISSN 1550-5952. PMC 2695719. PMID 19724716.

- ↑ Banaji, Mahzarin (2011). "Evidence for Hypodescent and Racial Hierarchy in the Categorization and Perception of Biracial Individuals" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 100 (3): 492–506. doi:10.1037/a0021562. PMID 21090902. S2CID 15132903.

- ↑ Jones, Nicholas (September 2012). "2010 Census Brief: The two or more races population" (PDF).

- ↑ Lee, J; Frank, D (2004). "America's Changing Color Lines: Immigration. Race/Ethnicity, and Multiracial Identification". Annual Review of Sociology. 30: 221–242. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.30.012703.110519.

- 1 2 Gibbs, Jewelle Taylor (1987). "Identity and Marginality: Issues in the treatment of biracial adolescents". American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 57 (2): 265–278. doi:10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03537.x. PMID 3591911.

- 1 2 Poston, W.S. Carlos (1990). "The Biracial Identity Development Model: A Needed Addition". Journal of Counseling and Development. 67 (2): 152–155. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.1990.tb01477.x.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Rockquemore, Kerry Ann; Brunsma, David L.; Delgado, Daniel J. (March 2009). "Racing to Theory or Retheorizing Race? Understanding the Struggle to Build a Multiracial Identity Theory". Journal of Social Issues. 65 (1): 13–34. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.01585.x.

- ↑ Stonequist, Everett V. (1937). The Marginal Man: A Study in Personality and Culture Conflict. New York: Russell & Russell. ISBN 9780846202813.

- 1 2 Hall, R.E. (2001). "Identity Development Across the Lifespan: a biracial model". The Social Science Journal. 38 (38): 119–123. doi:10.1016/S0362-3319(00)00113-0. S2CID 144037574.

- 1 2 Shih, Margaret; Sanchez, Diana T. (2005). "Perspectives and Research on the Positive and Negative Implications of Having Multiple Racial Identities". Psychological Bulletin. 131 (4): 569–591. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.569. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 16060803.

- ↑ Miville, Marie L.; Constantine, Madonna G.; Baysden, Matthew F.; So-Lloyd, Gloria (2005). "Chameleon Changes: An Exploration of Racial Identity Themes of Multiracial People". Journal of Counseling Psychology. 52 (4): 507–516. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.52.4.507. ISSN 1939-2168.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Renn, Kristen A. (2008). "Research on biracial and multiracial identity development: Overview and synthesis". New Directions for Student Services. 2008 (123): 13–21. doi:10.1002/ss.282.

- ↑ Cross, W (1987). Phinney, J.S. (ed.). A two-factor theory of Black identity: implications for the study of identity development in minority children. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Root, Maria (1990). Resolving "Other" Status: Identity Development of Biracial Individuals. The Haworth Press. pp. 185–205.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Renn, K; Shang, Paul (2008). "Research on Biracial and Multiracial identity development: Overview and synthesis". New Directions for Student Services. 2008 (123): 13–21. doi:10.1002/ss.282.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Miville, M. L.; Constantine, M. G.; Baysden, M. F.; So-Lloyd, G. (2005). "Chameleon changes: An exploration of racial identity themes of Multiracial people". Journal of Counseling Psychology. 52 (4): 507–516. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.52.4.507.

- 1 2 3 Donahue, Lindsy; Juarez, Judy (n.d.). "Kristen Renn's Ecological Theory on Mixed-Race Identity Development" (PDF). Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ↑ Mawhinney, L.; Petchauer, E. (2013). "Coping with the crickets: A fusion autoethnography of silence, schooling, and the continuum of Biracial identity Formation". International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education. 26 (10): 1309–1329. doi:10.1080/09518398.2012.731537. S2CID 144309296.

- ↑ Renn, Kristen A. (June 2008). "Research on biracial and multiracial identity development: Overview and synthesis". New Directions for Student Services. 2008 (123): 13–21. doi:10.1002/ss.282.

- ↑ Snyder, Cyndy R. (2016). "Navigating in murky waters: How multiracial Black individuals cope with racism". American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 86 (3): 265–276. doi:10.1037/ort0000148. ISSN 1939-0025. PMID 26845045.

- 1 2 3 Swanson, Mahogany (August 2013). "So what are you anyway?". American Psychological Association. American Psychological Association. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- ↑ Bracey, J. R.; Bámaca, M. Y.; Umaña-Taylor, A. J. (2004). "Examining ethnic identity and self-esteem among biracial and monoracial adolescents". Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 33 (2): 123–132. doi:10.1023/b:joyo.0000013424.93635.68. S2CID 143859335.

- ↑ LaFromboise, T.; Coleman, H.; Gerton, J. (1993). "Psychological impact of Biculturalism: evidence and theory". Psychological Bulletin. 114 (3): 395–412. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.395. PMID 8272463.