| Mier expedition | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The Drawing of the Black Bean, Frederic Remington | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 836 | 750 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

40 killed 60 wounded |

64 killed and wounded 242 captured (18 later executed) | ||||||

The Mier expedition was an unsuccessful military operation launched in November 1842 by a Texian militia against Mexican border settlements; it was related to the Somervell expedition. It included a major battle at Ciudad Mier on December 26 and 27, 1842, which the Mexicans won. The Texian attack was launched partly in hopes of financial gain and partly in retaliation for the Dawson Massacre (as named by Texans) earlier that year, in which thirty-six Texas militia were killed by the Mexican Army. Both conflicts were part of continuing efforts by each side to control the land between the Rio Grande and Nueces River. The Republic of Texas believed that the territory had been ceded to it in the Treaties of Velasco by which it gained independence, but Mexico did not agree. The expedition is best known for the Black Bean Episode, in which the Mexican Army decimated escaped prisoners, selecting for execution one in ten prisoners by drawing beans from a pot.

Background

Antonio López de Santa Anna, the ruler of Mexico, was defeated by Texians at the Battle of San Jacinto and signed the Treaties of Velasco in 1836, ceding Texas territory from Mexican control (these treaties had not been ratified by the Mexican legislature). However, his forces continued to invade the Republic of Texas with the goal of regaining control, particularly of the territory between the Rio Grande and Nueces River. Texas had hardly any settlements there.

On September 17, 1842,[1] Texian and Mexican forces engaged at Salado Creek, east of San Antonio. After a separate favorable Texian engagement earlier in the day, a reinforcement company of 54 Texas militia, mostly from Fayette County, under the command of Nicholas Mosby Dawson, began advancing on the rear of the Mexican Army. The Mexican commander, General Adrián Woll, sent 500 of his cavalrymen and two cannons to attack the group. The Texians held their own against the Mexican soldiers, but their fatalities mounted after the cannons came within range. The battle lasted just over an hour, resulting in 36 Texians dead and 15 captured in what Texans called the Dawson Massacre.

Expeditions

Alex Somervell and 700 Texas soldiers took off for San Antonio to punish the Mexican army for raiding parts of Texas, on November 25, 1842. The soldiers had regained control of Laredo on December 7, 1842, with 700 soldiers. The same day, Alex Somervell and his soldiers took over the town of Guerrero. By the time they took over the town, there were only 500 soldiers left from regaining Laredo (Guerrero was owned by Mexico). Lacking soldiers, Somervell ordered his men to return from the expedition on December 19, 1842. More men joined the Texan's force at La Grange; they then Marched to Ciudad Mier under the command of William S. Fisher. The expedition then failed.

Battle of Mier

| Battle of Mier | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

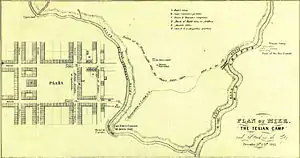

A map of the Battle at Ciudad Mier | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 836 | 350 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

40 killed 60 wounded |

64 killed and wounded 242 captured (18 later executed) | ||||||

Sam Houston ordered the expeditionary force to pull back from the Rio Grande to Gonzales but only 400 soldiers retreated as ordered. On December 20, 1842, the remaining 350 Texan soldiers under the command of William S. Fisher, approached Ciudad Mier. They camped on the Texas side of the Rio Grande and proceeded to participate in the capture of the town.

The Texans were unaware of the true number of Mexican troops stationed within the town. Once inside the city, the Texan soldiers were ambushed from their flanks and eventually surrendered in order to avoid the infamous Degüello.

The Mexicans army took 243 Texans as prisoner and marched them toward Mexico City via Matamoros, Tamaulipas, and Monterrey, Nuevo León.

On February 11, 1843, 181 Texans escaped but, by the end of the month, the lack of food and water in the mountainous Mexican desert resulted in 176 of them surrendering or being recaptured. This was in the vicinity of Salado, Tamaulipas.

When the prisoners reached Saltillo, Coahuila, they learned that an outraged Santa Anna had ordered all the escapees to be executed, but General and Governor Francisco Mejia of the state of Coahuila refused to follow the order.[2] The new commander, Colonel Domingo Huerta, moved the prisoners to El Rancho Salado. By this time, diplomatic efforts on behalf of Texas by the foreign ministers of the United States and Great Britain led Santa Anna to compromise: he said one in ten of the prisoners would be killed.

Black Bean Episode

To help determine who would die, Huerta had 159 white beans and 17 black beans placed in a pot. In what came to be known as the Black Bean Episode or the Bean Lottery, the Texans were blindfolded and ordered to draw beans. Officers and enlisted men, in alphabetical order, were ordered to draw. The seventeen men who drew black beans were allowed to write letters home before being executed by firing squad. On the evening of March 25, 1843, the Texians were shot in two groups, one of nine men and one of eight. According to legend, Huerta placed the black beans in the jar last and had the officers pick first, so that they would make up the majority of those killed.

The first Texan to draw a black bean was Major James Decatur Cocke. A witness recalled that Cocke held up the bean between his forefinger and thumb, and with a smile of contempt, said, "Boys, I told you so; I never failed in my life to draw a prize." He later told a fellow Texan, "They only rob me of forty years." Fearing that the Mexicans would strip his body after he was dead, he removed his pants and gave them to a companion whose clothing was in worse shape. He was shot with the sixteen others who drew black beans on March 25, 1843. His last words were reported to have been, "Tell my friends I die with grace."

The other sixteen who drew black beans in the lottery were William Mosby Eastland, Patrick Mahan, James M. Ogden, James N. Torrey, Martin Carroll Wing, John L. Cash, Robert Holmes Dunham, Edward E. Este, Robert Harris, Thomas L. Jones, Christopher Roberts, William N. Rowan, James L. Shepherd, J. N. M. Thomson, James Turnbull, and Henry Walling. Shepherd survived the firing squad by pretending to be dead. The guards left him for dead in the courtyard, and he escaped in the night but was recaptured and shot. Eastland County, Texas, is named after William Mosby Eastland.[3]

Captain Ewen Cameron had drawn a white bean, but was ordered executed anyway by Santa Anna a month later while being held at Perote Prison. As he waited to die, Cameron refused to confess to a priest.

The survivors who picked white beans, including Bigfoot Wallace and Samuel Walker, finished the march to Mexico City. They were later imprisoned at Perote Prison in the state of Veracruz, along with the 15 survivors of the Dawson Massacre and about 35 other men captured by General Adrián Woll in San Antonio. Some of the Texans escaped from Perote or died there. Most were prisoners until they were released, by order of Santa Anna, on September 16, 1844.

Legacy

In 1847, during the Mexican–American War, the U.S. Army occupied northeastern Mexico. Captain John E. Dusenbury, a white bean survivor, returned to El Rancho Salado and exhumed the remains of his comrades. He traveled with the remains on a ship to Galveston, and by wagon to La Grange in Fayette County, Texas.

La Grange citizens retrieved the remains of the men killed in the Dawson Massacre from their burial site near Salado Creek in Bexar County.

The remains of both groups of men were reinterred in a ceremony attended by 1,000 people. They were buried in a large common tomb in 1848, in a cement vault on a bluff one mile south of La Grange. The grave site is now part of a state park, the Monument Hill and Kreische Brewery State Historic Sites.

The Black Bean Episode is the subject of Frederic Remington's painting The Mier Expedition: The Drawing of the Black Bean.[4]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Lord, George. The Mier Expedition Archived 2010-12-05 at the Wayback Machine. (From clippings from the Cuero Star, Cuero, Texas (1883) and present in the Valentine Bennet Scrapbook by Miles S. Bennet, Center for American History, University of Texas, Austin). Retrieved June 21, 2014.

- ↑ Nance, J. Milton. MIER EXPEDITION," Handbook of Texas Online. accessed June 21, 2014. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

- ↑ "Black bean episode", Handbook of Texas Online, published by the Texas State Historical Association; Retrieved May 02, 2011

- ↑ Remington, Frederic. "The Mier Expedition: The Drawing of the Black Bean". Retrieved May 19, 2016.

References

- Abolafia-Rosenzweig, Mark. The Dawson and Mier Expeditions and Their Place in Texas History. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. 2nd printing April 1991.

- Interpretive Guide to: Monument Hill/Kreische Brewery State Historic Sites. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

- Lord, George. The Mier Expedition. (From clippings from the Cuero Star, Cuero, Texas (1883), and published in the Valentine Bennet Scrapbook by Miles S. Bennet, Center for American History, University of Texas, Austin). Retrieved June 21, 2014.

- Nance, J. Milton "Mier Expedition". from The Handbook of Texas Online. Texas Historical Association. Retrieved June 21, 2014.

- Nance, J. Milton. Dare-Devils All: The Texan Mier Expedition, 1842-1844, 1998 posthumous edition, Archie P. McDonald

External links

- Mier Expedition from the Handbook of Texas Online

- Drawing of the Black Bean painting by Frederic Remington, Museum of Fine Arts Houston

- Francis M. Dimond Mier Expedition Papers. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.