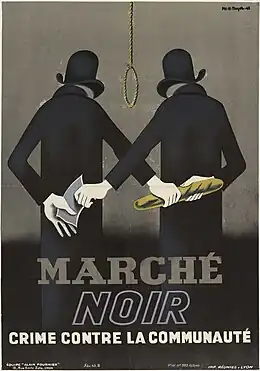

After the defeat of France in 1940, a black market developed in both German-occupied territory and the zone libre controlled by the Vichy regime. Diversions from official channels and clandestine supply chains fed the black market. It came to be seen as "an essential means for survival, as popular resistance to state tyranny invading daily life, as a system for German exploitation, and as a means for unscrupulous producers and dealers to profit from French misery."[2] It involved smugglers, organized crime and other underworld figures, union leaders and corrupt military and police officials. It later became a civil disobedience movement against rationing and attempts to centralize distribution, then eventually evading Nazi food restrictions became a national pastime. Those who could not, such as long-term psychiatric patients, simply did not survive.

Vichy market regulation was the first French attempt at economic planning. The parallel economy undermined the official centralized attempts to regulate the production, storage, transport, quantity, quality and price of food. Even after the liberation of France and the end of the Second World War, problems with supply kept rationing and the black market in operation until 1949.

Background

1930s: inflation, instability and unrest

French politics were very unstable in the 1930s. Twenty-one different governments formed in the Assemblée Nationale in that decade, some of them only in office for days. Subsequent changes to the French Constitution under the Fourth and Fifth Republic made it more difficult to hold a vote on a motion of no confidence and thereby force the dissolution of the government.

In the 6 February 1934 crisis multiple far-rightist leagues rioted on the Place de la Concorde near the French National Assembly. The police shot and killed 15 demonstrators. Elections were called over this, even though a popular prime minister had just been elected. The Popular Front formed around the socialist SFIO and won the 1936 elections. Léon Blum became the first socialist prime minister of France. Two million workers seized factories and stores in a wave of strikes, brought on by dissatisfaction with the state of the Depression-era French economy. Blum negotiated the reforms of the Matignon Accords with the labour unions.[3][4] The wage and hour concessions that emerged from the strikes have been blamed by some economists for the runaway inflation and subsequent stagflation that ensued, but more recent studies indicate that delay and reluctance to devalue the franc and abandon the gold standard were also factors, and possibly more important.

After 1935 inflation was a recurring theme in the French economy.[5] Wage increases agreed to by the administration of Léon Blum further stimulated the economy, increasing inflationary trends.[6] After the German occupation, Vichy printed money to make the ruinous payments Germany demanded to cover its inflated estimate of its occupation costs, pushing inflation to 27%.[7] "Yet, once they imposed huge occupation payments, the victors left the French to decide how to raise the funds and contend with passive and active resistance from the population."[8]

Fall of France

After the Battle of France and the armistice with Germany, France was split into the Vichy government controlled zone libre ("free zone"), Pas-de-Calais, Nord and the zone interdite under the German military, the zone occupée under German control in the remainder of Northern France.[lower-alpha 1] Italy occupied part of France on the Mediterranean coast and Alsace Lorraine[lower-alpha 2] was annexed by Germany.[9]

During the war black markets arose when government imposed quotas and regulations to control supply and distribution, and demand exceeded supply;[10] a phenomenon described as "the free market at its most brutal."[10]

1940-1941

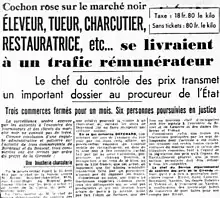

From late 1940 onwards, the black market became a widespread and almost universally condemned practice. Its very existence called into question the policies of the Vichy government, which in turn tried to suppress it.[11][12] More than a million black market citations were issued during the four years of the occupation.[13]

As a matter of policy, the German Army stripped France and the other countries it occupied of their output and assets; "the Germans embarked immediately upon the general requisitioning of all raw materials and all goods in the occupied countries," said Francois de Menthon, the French prosecutor at the Nuremberg trials in his address to the court.[14] The German Military Commander for France reported on 10 September 1942 (EC-267), that since the Armistice 73 percent of the normal annual French consumption of iron, nearly 5 million tons, went to Germany. Up to July 1942, 225,000 tons of copper and 5,700 tons of nickel went to Germany: 80 percent and 86 percent of the French supply respectively, as well as 55 percent of its aluminum and 80 percent of its magnesium production. France could keep only 30 percent of the normal production of the wool industry, 16 percent of the cotton production, and 13 percent of the linen production. All locomotives produced in France, and most of its machine tool production, went to the Nazis.[15]

Origins

Under Article 18 of the Armistice of 22 June 1940 France agreed to pay "occupation costs", but in a violation of the Hague Conventions, Germany demanded 400 million francs a day, an extravagant sum, a total of 479 billion francs from 1940 to 1944. The levy went down in 1941 to 300 million francs a day, then increased to 500 million a day by 1943 as the Germans began to lose the war.[16] At one point a quarter of the French GDP,[17] in 1943 the payments were equivalent to 55.5 percent of French economic output.[16] German diplomat Hans Richard Hemmen testified after the war that the figure assumed three million German soldiers in France, and that these sums were spent on the black market, "a clear misuse of the money."[18]

The Germans also required the French to finance the transportation of exports to Germany, and paid for their purchases with special currency pegged to an exchange rate that was artificially advantageous to them,[19] at 20 francs to one Reichsmark.[20][21] The French economy, blockaded and in a state of disarray, was largely inactive at the time,[22] and had been chaotic and plagued by runaway inflation for years before the armistice.

Rationing and price controls

| Class | Category |

|---|---|

| E | Children up to 3 years old |

| J1 | 3 to 6 years old |

| J2 | 7 to 13 years old |

| J3 | 13 to 21 years old |

| A | 21 to 70 years old |

| V | Over 70 years old |

| T | Workers |

| C | Farmers |

Vichy retained control of economic policy across both zones, subject to the approval of the Germans in the occupied zone.[26] The decree of 30 July 1944 instituted rationing of sugar, pasta, rice, soap and fats. Starting on 23 September 1940, Vichy set up a top-down agricultural supply system as well as an authoritarian distribution of raw materials and industrial products. For consumers this meant food rationing, which they were told would ensure a more even distribution and prevent excessive influence of price on availability.[11] At this point the nascent black market took off.[11]

French people were classified by age or occupation group, according to eight categories.[23][24][25] (see Table 1)

To buy goods, consumers needed government tickets authorizing them to buy a certain quantity. Starting in the autumn and winter of 1940–1941, bread, sugar, milk, butter, cheese, oil, meat, coffee and eggs were all rationed, as was coal.[11][27][28] In 1941, rationing was further extended to chocolate, produce, shoes, textiles and tobacco.[11][27][28] Non-smokers who drew their ration anyway fed it into the black market.[29]

The caloric value of French rations was insufficient for a healthy diet.[30] Historian Kenneth Mouré, an authority on the period, wrote in 2022 that this was deliberate, "to punish French civilians", and set to match conditions in Germany's World War I Turnip Winter.[31] For category A (adults), rations provided on average around 1,080 calories a day, while an adult man needs around 2,200 calories.[30] This energy intake allowance was the lowest level in any western country over the 1940–1944 period; rations in Belgium for example had a calorific value of 1800 and in Germany over 1900.[30] This shortfall resulted in malnutrition, which led to higher mortality, stunted growth, vitamin deficiency and more cases of tuberculosis and diphtheria.[30] In the first three months of 1941, some 113 people were arrested for stealing rabbits or chickens in the impoverished southern region of Hérault, compared to three over the same period the year before. In July and August 1941, 429 people were arrested for stealing food, and there were 159 "other" thefts, most of which also had links to other shortages.[32]

Stores often did not have enough inventory to provide the ration allowance of food; so people found food elsewhere. Large employers were mandated to provide employee canteens, and some people were able to grow vegetables, buy directly from farms, or have rural family members ship them food. There was also the black market.[27] Those with no access to these resources, such as internees or patients in psychiatric hospitals, often suffered starvation: 45,000 patients died in French psychiatric hospitals during the Occupation.[33] In the small Italian occupation zone in Menton, the situation was less serious, and rationing did not begin until July 1941.[34]

Diversion from official channels

From the start the black market was fed by products diverted from their official channels. Wholesalers took advantage of geographical differences in price.

On 19 May 1941, Vichy imposed price controls on fruit and vegetables, which had had none until then. Merchants in the Paris region sent telegrams to provincial suppliers asking them to redirect their shipments to regions where prices were highest. Parisians found themselves without fruit and vegetables for several days. In the end, the authorities had to relent and raise prices in Paris, while the affair, reported in the press as the "telegram affair", stirred up public opinion.

Wholesalers also put pressure on retailers to pay them kickbacks, to ensure they were kept supplied.[35]

Clandestine networks

Supplies for the black market also came from channels entirely outside the official system. Many smugglers were SNCF (French railway) employees or retirees with free rail passes. For example, of 51 official reports on smugglers in February 1941 in the Rodez area, 41 concerned railway workers.[36] The gendarmes in Ille-et-Vilaine noted in April 1941 that "on certain market days, the passenger carriages are so crowded with employees and their parcels that it is impossible for a passenger, or even a ticket inspector, to cross part of the carriage".[37]

Hidden stockpiling

Many producers and traders hid their stockpiles, particularly of industrial raw materials.[38][39] In the Tarn 8,000 t (7,900 long tons; 8,800 short tons) of wool and cotton were allegedly hidden from the Germans, then supplied to the clandestine textile industry. Even when in autumn 1940 Vichy required businesses to report their inventories, much still went unreported. This unreported inventory, of wood or leather for example, then became available for sale through black market channels.[38]

Black market transactions between farmers and consumers increased considerably. Farmers withheld a portion of their production from the official harvest collections of the service du Ravitaillement ("resupply service"). Official nationwide production dropped 35% from the first three months of 1941 compared to the same period in 1942.[40][41] Similarly in 1942 pork disappeared altogether from government channels; only 24 porkers were available in Seine department from July to December. In February 1943 German requisitions and French fixed costs exceeded available resources by thirty percent and that disparity continued until the end of the occupation. So by June, more than two thirds of the cattle market was diverted to the Germans and by 1944 the German cattle requisition had tripled since 1941.[42]

Grey market

From the end of 1941 to 1943, a "grey market" emerged in which more and more city dwellers travelled into the country for their groceries. The prefect of Ardèche reported that at the height of the trend, as many as two thousand people a day cycled into the countryside to buy food. City-dwellers paid farmers more than the official price, but less than the official urban retail price for consumers. This became common practice and no longer seemed immoral once survival required it and the Catholic Church no longer condemned it.[43][44]

Under the law of 15 March 1942, Vichy had de facto tolerated small-scale black market activity and concentrated on large-scale trafficking.[45] The black market and the grey market at that point accounted for around 30% of national agricultural production,[46] and were most extensive near large cities, especially Paris. The profits mostly however went to upstream wholesalers and large-scale suppliers rather than to smaller growers or merchants."Many black-market profiteers seemed, to the citizens they had exploited, to escape punishment, Mouré wrote in 2023: "The breadth of the black market and its ‘essential’ nature for survival made postwar justice appear flawed: black-market practices continued, some newly re-legalized, and the state opted in 1947 for fiscal measures to tax rather than punish the actors and activities needed for reconstruction."[2]

Users of the black market

Privileged French

In the early years of the war, most Parisians spent long hours queuing for food.[47] Riotous buying by Germans had created a bubble that made the black market inaccessible to the general population. French clients of the black market were from the most affluent layers of society, and escaped restrictions on their daily lives. They lived in the richest parts of the country, in Paris and in tourist destinations such as Deauville, Nice and Megève. They bought food, but also clothes, coal and gasoline.[48] Restaurants in particular were an ongoing example of the social inequities of the time, as the prices they charged were unaffordable to most Parisians.[49]

Luxury estaurants supplied themselves on the black market and served many more dishes than their customers' ration coupons permitted, going well beyond their officially posted menus. An enforcement operation in early 1941 found violations of the black market code in almost half of the restaurants it checked.[50] In April 1941, a police report pointed out that Le Lido and Fouquet's were using underground suppliers, and by November 2019 Paris police were reporting that if rationing were enforced, many restaurants would have to close.[50] Restaurant owners went themselves to the country and did their buying there. Luxury restaurants were at first protected because of their German clientele, but in summer 1941 an agreement between Vichy and the occupiers officially exempted some ten luxury restaurants in Paris from the rules, including Maxim's, frequented by many Germans including senior Nazi Hermann Göring; La Tour d'Argent; Fouquet's; the Carlton, the Drouant-Gaillon; and Lapérouse, frequented by journalists like the collaborationist Jean Luchaire.[51][48]

Occupation forces

The German occupiers were big clients of the black market. Individual soldiers and civilians made many purchases, benefiting from the artificially advantageous exchange rates; the French franc was fixed at 20 to the Reichsmark.[52] The way they emptied the stores of food, clothes and shoes strongly accentuated the shortages and the French quickly nicknamed German soldiers doryphores ("potato beetles").[53]

German military units organized their own bulk food purchases from farms, with no regard for regulations. These purchases were particularly numerous during the invasion of France in the spring of 1940, when the speed of the Blitzkrieg's advance over-extended their supply chains. The regions of Normandy and Brittany particularly suffered from this type of military resupply.[53]

Without coordination or prior planning, the Germam agents used black market networks to get hold of stocks of raw materials. The best-known of these buying agencies was bureau Otto, created in the fall of 1940 by an Abwehr (German intellegence) officer, Hermann Brandl, nicknamed Otto. Located in the 16th arrondissement of Paris with warehouses in Saint-Ouen and Nanterre, bureau Otto, which at the beginning of 1941 employed more than 400 workers, was one of the largest underground networks.[54][53][55]

About 15% of the funds paid to Germany by France during the occupation were spent on black market purchases,[55] a report from the French army’s general staff in March 1942 estimated that "each day the Germans were passing more than 100 million francs worth of merchandise from the free zone to the occupied zone."[52]

The Germans offered protection and passes to French middlemen.[56] The most well-known of these collaborators included Georges Delfanne, known under the pseudonym of "Masuy", and Henri Lafont, head of the gang at rue Lauriston, which became known as the Carlingue. Another notable collaborator was Frédéric Martin, known by the pseudonym Rudy von Mérode, who with the help of the Devisenschutzkommando, seized gold from traffickers who used the black market on pain of arrest and managed to collect over four tons.[57] They also used established merchants, competent opportunists who built fortunes, such as Joseph Joanovici in scrap metal or Michel Szkolnikoff in textiles.[58] [59][60][55]

The true profiteers were the professionals: Joseph Joanovici and Mandel Szkolnikoff, corrupt businessmen like the fake Baron de Wiet, and errant aristocrats like Marie Tschernitcheff. They headed sophisticated networks, built fortunes and lived large. Through the black market, Szkolnikoff became one of the biggest real estate owners in France, with a hundred-odd exclusive buildings in Paris, luxury hotels in resort towns, a game preserve in Sologne and a chateau in Saône-et-Loire.[58][61][60]

Public response

Early condemnation

From 1940 to the end of 1941, the black market was considered shameful. Its principal clients were either rich Frenchmen and or officers in the occupying forces, which had organized purchasing agencies (French: bureaux d'achat).

The difficulties of daily life and the inefficiency of the supply system compounded the resentment of consumers toward the black market. Yet tactical errors in enforcement increased the negative perceptions of the French State, whose efforts to control the black market focused on retail violations of price and ration regulations and the illicit transport the enabled them, because they were easier to investigate[62] than large-scale diversions of raw materials on the industrial market rationed goods, and de Sailly believed that exemplary punishments would bring the black market under control.[62] But continuing food shortages increased consumer demand, while price controls "encouraged greater diversion of goods". And yet enforcement focused on rationing, "maximising their interference with consumers seeking essential goods."[62]

Buyers and sellers shared an interest in evading controls. Closer market supervision... increased public irritation and encouraged the diversion of goods to black markets. The state’s inability to provide sufficient food and contain black market growth was a major factor in the rapid loss of public confidence in the Vichy regime.[62]

From November 1940 on, public opinion increasingly distanced itself from the regime. Complaints about the difficulties of getting food and clothing became very numerous.[63] and "...the system of controls and rationing was inexorably losing legitimacy."[62]

Participation

In 1943–1944, using the black market became a patriotic act. The Germans increased their economic pillage, but stopped buying on the black market, and demanded more stringent enforcement from Vichy. The paramilitary Vichy milice participated in the crackdown."Evading food restrictions became something of a national pastime"[64] The French resistance groups encouraged this, building on widespread resentment in the countryside against Vichy. Vichy authorities for their part depicted resistance fighters as black market bandits.

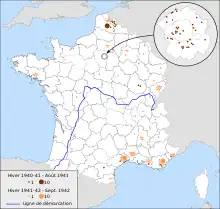

Housewives' demonstrations

In the face of restrictions, women were on the front line.[66] From 1941 onwards, so-called housewives' demonstrations were organized to protest against supply problems and the black market. They were numerous demonstrations from November 1940 to July 1941, then from November 1941 to September 1942, in Paris, but also in the Nord and Pas-de-Calais departments, along the Mediterranean coast from the Pyrénées-Orientales to the Alpes-Maritimes, and in the Doubs, Calvados and Morbihan departments. Mostly involving women, the protests were often relatively spontaneous and rarely explicitly political, and the demands expressed immediate needs for foodstuffs and other essential items.[67][68][69]

In the Nord department, these demonstrations were supported or instigated by L'Humanité and the Communist resistance.[68][70] More generally, as they were essentially made up of women defying men who represented authority, they were a specifically feminine form of resistance, extending a difficult daily life and making women visible.[66] These demonstrations weakened the Vichy regime and contributed to a gradual breakdown in relations between the regime and the population.[63][69]

Suspicions of hoarding

To ordinary citizens queuing for insufficient food supplies, the existence of the black market seemed to prove that the shortages were artificial and caused by diversion of supplies. It seemed as though the plenty available to those who could pay led to a perception that the shortages were caused by the black market itself.[71]

Vichy encouraged informers.[72] The populace sent between three and five million letters of denunciation during the occupation.[72] Those about the black market had three particular targets: shopkeepers, farmers and Jews. These letters, very often poorly spelled, seem to have come from those suffering the most from the shortages, but were also sometimes used to avenge old grievances.[72]

When city shopkeepers had to close for lack of merchandise, they were suspected of selling at higher prices on the black market, although they had real difficulties obtaining supplies at all. Housewives who spent hours queueing only to receive insufficient quantities saw retailers as a kind of "local tyrant(s)" as the prefect of Seine noted in May 1942. Over the course of 1941, the theme of the "profiteering farmer" developed in public opinion arousing hostility in the towns.[73]

Official antisemitism

Official Vichy propaganda blamed Jews for the black market.[74] Xavier Vallat, director of the Commissariat-General for Jewish Affairs, used it as a pretext to justify the Second law on the status of Jews, which came into effect on 2 June 1941. The prevailing propaganda played on conspiracy theories and anti-semitism that had long been rife in France, well before the war. Popular opinion saw Jews as monopolizing foreigners, "living in an opulence that caused scandal".[71]

Anti-semitic tropes blaming Jews for the black market arose in the countryside of the zone libre in 1940–1941, and more generally in places with many wealthy refugees, such as the Var coast.[72][73] Public opinion targeted refugees in general, not just Jews. But because of legislation that discriminated against them, forbade them certain professions and deprived them of income, Jews were reduced more often than others to using the black market, and while anonymous letters were usually ignored, this was not the case when it came to Jews.[72]

Public opinion

Public opinion held that the black market had developed because the administration was not efficient enough and was too timid in its enforcement. Its very existence seemed to belie Pétain's promises. The black market, which favored the wealthiest, underlined social contrasts and the abuse of privilege which began from the very start, at the highest levels of government.[75] This resentment was fueled by the major scandal known as the 'Meals on Wheels' affair, when from March to September 1941, a large number of buyers drove around in vans to buy food from farmers and were subsequently fined in the Allier department. They were actually intermediaries buying food for the ministries based in Vichy> When the director of food services was questioned he stated that "his superiors closed their eyes to the use of clandestine methods".[76] Pétain gave them an amnesty on 12 August 1942.[63]

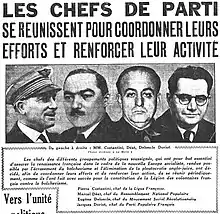

Political opposition

The black market was used by political opponents of Vichy. After Pierre Laval was ousted from the Vichy government[lower-alpha 3] on 12 December 1940, the Parisian collaborationist press, controlled by the occupier, openly criticized the Vichy regime, blaming it for supply shortages and insufficient enforcement of black market regulations. The collaborationist parties that emerged in 1941, Marcel Déat and Eugène Deloncle's National Popular Rally and Jacques Doriot's French Popular Party (PPF), developed the same themes. The Communist Party also denounced the black market, but lay responsibility for it not just with Vichy, but also with the occupying forces.[63]

Response by authorities

The black market was a continual preoccupation for the Vichy regime. Between February and November 1941, François Darlan's Council of Ministers met to discuss the issue on ten occasions; the existence of the black market implied a failure of their supply policy.[77]

A decree dated 17 September 1940 created the Contrôle Economique under the Ministry of Economics and Finance. This department gradually built up a nationwide administration of retired civil servants, customs agents and financial services staff, headed by Jean de Sailly, the Inspector of Finances.[78] Two investigative bodies were created, one in Paris, one in Vichy, along with departmental and regional units.[79][80] Agents were trained to investigate specific industries.[77][78][81]

Price controls introduced by Vichy were based on three incorrect premises:

- collaboration would benefit the French

- price controls would curb inflation

- the French would adapt and accept price controls.[79][2]

The law of 7 December 1940 created supply inspectors who checked cards and tickets as well as the official declarations when a harvest was brought in or products were transported. On 26 November 1940 the Police Economique (Economic Police) were created, directly responsible for combating the black market.[82] Its local brigades were extended to the whole of France in 1942. The economic police investigated more thoroughly and at greater length than the other two departments, and were responsible for armed interventions when needed.[77][83]

The police and gendarmerie carried out operations against the black market, particularly the gendarmerie, which covered the whole country. The Légion Française des Combattants (French Legion of Veterans) would have liked to play a role also, but were refused permission.[77]

At the end of 1941 and into early 1942 participation in the black market became more general on both the supply and the demand side. A new expression appeared: "grey market". The Vichy regime was forced to adapt and relax its enforcement policy.[84]

Widespread black market (autumn 1941 to 1943)

The end of 1941 and the beginning of 1942 marked a turning point. Participation in the black market became more general on both the supply and the demand sides of the market.

After the Allies invaded French North Africa in November 1942 and the French forces there joined them, Germany implemented Case Anton and occupied the remainder of metropolitan France, known until then as the zone libre. The remaining French army was disbanded.

Agricultural black market

As it did in Ukraine, its other large agricultural acquisition, Germany relied on existing administrative structures to enforce its requisitions and supply restrictions.[85] Sales by farmers to consumers increased considerably. Farmers withheld some of their production from the official collections of the service du Ravitaillement (resupply service). Official nationwide production dropped 35% from the first three months of 1941 to the first three in 1942.[40][41]

| Food | Amount |

|---|---|

| Bread grain (wheat, rye) | 2,950,000 tons |

| Secondary cereals (oat, barley) | 2,431,000 tons |

| Straw and hay | 3,788,000 tons[87][88] |

| Meat | 891,000 tons |

| Eggs | 311.3 millions[87] |

| Fats (margarine, tallow, oils) | 51,200 tons |

| Oils | 39,400 tons |

| Butter | 88,000 tons |

| Potatoes | 752,000 tons[88] |

| Sugar | 99,000 tons[88] |

| Wine | 10,400,000 hectoliters |

| Milk | 1,445,000 hectoliters |

| Cheese | 45,000 tons |

In Mayenne, 1943 collections brought in 47 million litres of milk and 1.4 million kilograms of butter compared to 125 million litres of milk and 5.15 million kilograms of butter in 1937.[89] In nearby Calvados, a major butter producer, butter became increasingly rare because of the German resource drain then disappeared from official channels and could only be found on the black or grey market.[90]

In Eure-et-Loir in 1942, the vegetable collection brought in 4,300 (metric) tons compared to the projected 7,400. In the Aisne, half of livestock declared were undervalued.[40] Before the war the commune of Sagy (Saône-et-Loire) supplied 200 tons of beans to the wholesalers in Louhans. In 1941–1942, the official harvest was only 10.8 tons; the rest was sold on the black market.[91] Farmers were also reticent about declaring their harvest for collection because they considered it unfair. In Chinon and Louhans, farmers contested the valuation of livestock and suspected butchers and officials of collusion.[89]

Ill-will was sometimes a rejection of the occupation and a form of passive resistance, but in the zone libre it was principally rejection of the Vichy regime. The nomination of former agarian leader Jacques Le Roy Ladurie as Minister of Agriculture and Supply (Agriculture et du Ravitaillement) in April 1942[92] did not dissipate this defiance. Price controls were less and less accepted, while constraints imposed by the supply system were rejected by many farmers.[40][41]

When they circumvented the rules, farmers did not feel they were cheating but simply selling, at the best price available, the fruit of their labour.[40] In their eyes the Vichy regime was returning to ancient fiscal practices of an all-controlling state against which they needed to defend their economic well-being.[90] The French countryside was filling with dissidents.[93]

Sales by farmers directly to consumers became more common, because consumer demand increased. Rationing was becoming stricter and official rations more inadequate, dropping to 1,100 or 1,200 calories a day for adults. Very often shortages were so dire that consumers could not obtain the limited quantities they were entitled to buy, making the black or grey market their only recourse.[40]

Grey market: direct sales

Starting in the summer of 1941, city-dwellers began to go, often on bicycles, directly into the countryside to buy food, short-circuiting the middlemen. This became known as the grey market. The journalist Alfred Fabre-Luce wrote in his personal journal, "It is better to buy at the farm at a high price than to buy from a middleman at an insane price".[94] Sometimes dedicated bus services sprand up, or as in the case of Valence, a taxi service.[95] In November 1941, the Ardèche préfet noted that more than two thousand cyclists had come from Valence in a single day for potatoes. Those who had family or relatives in the country of course had an advantage, while others were not always well received.[96]

To extend their reach beyond where they could go on bicycles and also to carry higher volumes, city dwellers began to catch trains in the morning carrying empty suitcases, get off at small-town stations, and return heavily laden the same day, especially on the Paris-Rouen, Paris-Chartres, and Paris-Orléans lines. In December 1942, police in Épernay seized more than 330 kg (730 lb) of wheat, 45 kg (99 lb) of oats, 65 kg (143 lb) of rye, 55 kg (121 lb) of barley, 72 kg (159 lb) of flour, 27 kg (60 lb) of meat, and 45 kg (99 lb) of lentils. Luggage searches were routine, but there were too many travelers for the inspectors to open every suitcase. The Paris train lines were particularly well-patrolled.[96]

Shipping food boxes was another method to make black market exchanges. Starting 13 October 1941, Vichy authorized farmers to ship food boxes to family members provided they were shipped by the farmers themselves and weighed less than 50 kg (110 lb). In October 1941 6,700 packages of food, roughly 13 metric tons, were leaving the sparsely populated agricultural department of Cotes-du-Nord every day.[97] From September 1941 to September 1942, German requisitions of butter more than doubled from 9.1 to 24.9 metric tons, and in November the Feldkommandantur imposed 53 million francs in fines on the communities with the greatest shortfalls when the official harvest collections "collapsed".[97][98]

In 1942, more than 13 million food packages were shipped nationwide weighing more than 279,000 tonnes (308,000 short tons) in total. These family packages soon gave cover to shipments that were actually commercial, noted the préfet of Creuse. These family packages kept many city-dwellers alive.[99]

In a circular of 16 August 1940, the French State encouraged the creation of business canteens, rare until then. Two circulars from December 1941 gave them priority in food distribution, but since they never stopped developing, they created parallel direct supply channels, sometimes managed by employees using obfuscated accounting records.

Barter became more and more common. A fishwife of Agde was cited in September 1941 for trading fish for potatoes, and workers from Vuillafans in Doubs exchanged nails from their factory for food.[100] Dunlop Rubber in Montluçon gave tires, which were extremely rare, to its workers so that they could barter them for food and Michelin in Clermont-Ferrand bartered tires for food for its employees.[96][101][101] In Calvados, a pair of shoes was worth 20 kg of butter.[90]

These unofficial channels improved the average daily base ration by 400 to 700 calories.[102] As these were only about 1,100 to 1,200 calories in 1942, these additional calories were important though still not enough for a properly fed population. Despite this general observation, many diverse examples existed, from worker canteens opened by big businesses to personal networks, especially in the country.[96]

Commerce and industry

As in agriculture, the black market became commonplace in all sectors of commerce and industry beginning in the second half of 1941. The restrictions were such that businesses could no longer function and remain within the law, except for those that produced for the occupier and therefore were able to obtain raw materials.[103]

The black market for raw materials got larger and larger. Businesses inflated their production estimates in order to obtain additional raw materials from official allocations.These surplus materials then fed various covert transactions. Having paid high prices for these materials, businesses sold part of their production for more than the official rate. It became normal to ask the buyer for a kickback, in other words the difference between the official price recorded in official records and the prevailing true price. This fraud involved issuing fake invoices and keeping two sets of books. Businesses used various secret codes, like the clockmaker from Doubs who used different-coloured tickets to indicate to the buyer the multiplying factor (4, 5, 6, or 7) of the official price that was needed to calculate the actual asking price for the item.[104][103]

The industries most affected by the general practice of the soulte were specialized local or regional industries that produced produced high-demand consumer goods. A market was assured despite the high prices: cutlery, leather, lumber and textiles.[103][104]

Beginning in 1940, forgery and the sale of faked ration tickets became a favored black marketeer tactic, which increased demand for paper and printing professionals.[105] A trial before the Tribunal d'État de Paris in March 1942 concerned 260,000 sheets of fake tickets, which would have bought 3 million kilograms of bread. These fake documents were often printed by real print shops, which made it easier to enforce the law. Distribution centres for cards, often in town halls, were sometimes looted.[24]

Tacit tolerance

Generalization of the black market came with a change in its depictions. Public opinion continued to decry the grand-scale black market in which some made their fortunes, but it condoned small daily compromises to survie, and therefore it no longer tolerated law enforcement targeting them.[106]

No longer immoral

Until the law of 15 March 1942, the régime did not distinguish between the black market and the grey market, and family supply was still illegal. For example, a farmer in Creuzier-le-Neuf was fined in April 1941 by a court in Cusset for having given 13 pounds of butter to some friends.[107]

Still, the black market was increasingly considered legitimate. The retail, grocery and artisanal professional associations did not condemn minor infractions, which were considered necessary given supply chain problems and thin profit margins. Only large-scale black market wholesalers were still condemned. This attitude implied criticism of the partition policy and a replay of the conflict between "the little guys" and "the big guys".[43]

Farmers were also defended. Henri Dorgères, a director of the Corporation paysanne, published in his Le Cri du Sol newspaper in Lyon letters from farmers who felt unjustly condemned for selling on the black market, and starting at the end of 1942, sent Pétain reports minimizing the implication of farmers in the black market.[43]

The discourse of Catholic Church changed in 1941. While the La Croix newspaper clearly condemned all forms of black marketing until the summer of 1941, the bishop of Arras, Henri-Édouard Dutoit, told the priests of his diocese in October 1941: "when the farmer has provided, at the legally-set price the required quota of foodstuffs, it seems to us that it is not illegal to ask a slightly higher price for any surplus he may still have."[43] On 13 December 1941, Emmanuel Célestin Suhard, Archbishop of Paris, emphasized the need to tolerate "modest illegal operations to obtain necessary food supplements, justified both by their small size and by the necessities of life."[43][44] Still, not all prelates were so indulgent: the bishop of Rodez, Charles Challiol, condemned the black market on 29 and 31 October 1941, a position he continued to hold afterwards.[108]

The social acceptance of small transactions led to a greater and greater rejection of enforcement and checkpoints. The proliferation of roadblocks in departements crossed by the line of demarcation[lower-alpha 4] like the Cher, primarily resulted in arrests of city-dwellers on bicycles bringing home a few kilos of food they had bought at a farm. These checkpoints seemed more and more unbearable and unjust. In Paris, in its editorial of 5 February 1942, Le Temps wrote: "Let them get their supplies when and how they can, by their own means, these unfortunate city dwellers for whom city markets most often offer only inadequate resources."[43]

Enforcement methods were questioned more and more, especially the one known as "provocation", in which the inspector pretended to be a customer. The population also accused the inspectors of corruption. A few cases did surface, but were rare among price control agents, though a little less so for supply control agents.[79][81] Their unpopularity made it harder to set up inspection points, as in for instance at Vitet near Bayeux, where on 28 July 1941, two hundred people (sailors, wholesalers and shopkeepers) tried to impede an inspection point and were only pacified by the intervention of the gendarmes.[81][109]

Growing acceptance of small black market transactions led to more and more rejection of enforcement and checkpoints. The proliferating roadblocks in departments crossed by the line of demarcation,[lower-alpha 4] like the department of Cher, primarily resulted in arrests of bicyclists with a few kilos of merchandise bought at a farm. These checkpoints seemed more and more unbearable and unjust. In Paris, in its editorial of 5 February 1942, Le Temps wrote:

"Let them get their supplies when and how they can, by their own means, these unfortunate city dwellers for whom city markets most often offer only inadequate resources."[43]

In general, the press presented the contrôle économique increasingly unfavourably.[79]

Nuanced and refocused enforcement

To avoid alienating public opinion, the Vichy regime lessened penalties for small infractions and concentrated on large-scale trafficking.[81][110] In August 1941, a local news story demonstrated the need to be less severe. Unable to bear the shame, a farmwife committed suicide after her conviction by the correctional court (tribunal correctionnel) of Charolles for selling butter without a ticket at a price slightly above the official rate. This incident greatly upset the population of Saône-et-Loire and set off an active correspondence between ministers.[110]

The law of 15 March 1942 established a distinction between deliberate profiteering on the black market, and small-scale illegal exchanges.[111] It increased penalties for the former but not for the latter. Those who only wanted their families to eat were not to be targeted. The law established three levels of judicial sanctions. Grey market transactions were still sanctionable, but under the prior law and therefore to a lesser extent. Store owners or individuals who engaged in unauthorized commerce were much more severely punished, liable to two to ten years in prison and fines from 200 to 10 million francs. Large-scale trafficking remained under the juridictions d'exception created by the preceding law. This new policy was well received by the public.[110][112] Still, in April 1942, police in the working-class town of Saint-Claude in Jura noted an increase in thefts of food, accompanied by a mysterious disappearances of cats.[113]

After the adoption of this law, the government reorganized enforcement. On 6 June 1942, it created the Direction générale du contrôle économique (DGCE), headed by Jean de Sailly. It was a section of the Ministère de l'Économie et des Finances and the successor of the service du contrôle des prix. Its authority included all economic regulation and all services were required to apply its directives, even if they were sections of a different ministry. Employee numbers increased and reached roughly 4,500 by the end of 1942. Under the law of 15 October 1942, the government abolished the contrôle mobile du ravitaillement and absorbed its agents into the DGCE, which permitted a big purge and the termination of a quarter of the agents.[79][80][81][110][114]

The law of 31 December 1942 ended this reorganisation. It centralized the collection of official reports on economic offences. These were then sent to the departmental director of the DGCE, who decided on a case-by-case basis whether to make an administrative decision or whether refer the matter to the judicial branch for follow-up.[81][110]

This reorganisation corresponded to new principles expressed by Pierre Laval in a circular to the prefects. Agents were to stop combatting small infractions and concentrate on large-scale trafficking. The gendarmes charged with investigating small markets were to "act openly and in uniform and to avoid unnecessary vexation." Agents assigned to fraud in industry were to understand and take into account the problems faced by businesses. DGCE became a true investigative service, which researched offenders and carried out in-depth investigations.[81][110] In practice, the Contrôle économique continued to focus on small transactions, because this was easier and, like other agencies, it lacked resources such as petrol.[79]

Metrics

The investigations of the DGCE created statistics, which, while partial and fairly approximate, permit an overall portrait in broad strokes of the black market.[115]

Proportion of production

The size of the black market varied by product. For 1943 agriculture, the black market in the narrow sense, in other words direct sales to traffickers at high prices, represented 10% to 20% of total production. Adding in the grey market and sales between friends increases the total to between 20 and almost 50% of total production (almost 50% for poultry, 35% for beans and eggs, 24% for potatoes, 22% for butter, 20% for meat.) Since farmers also produced for their personal and family consumption, the share of the official collection was less than that of the black market sales of poultry, dry vegetables or eggs. The meager size of the official collection was not primarily due to the black market, but rather to the significant portion of their production that traditional farm families consumed themselves.[115][116]

In industry, black market infractions didn't so much concern production, which for the most part followed authorized channels, as market conditions, particularly kickbacks. Anything could be found on the black market, but it seems to have been particularly well-developed for raw materials like wood, leather and paper. For paper, it reached half of all production in 1942.[117] Manufactured consumer goods, like shoes, clothing, bicycles, tires, and hardware, were often sold on the black market as a result of their scarcity.[115]

Higher and more volatile prices

Because of the black market's clandestine nature, sellers often had a monopoly and the growing imbalance between supply and demand allowed them to set their own price.[118]

Prices on the black market varied considerably according to the time, place or people involved. When the seller personally knew the buyer, in agriculture or in industry, the price could often be lower. Where there were chronic shortages, the price of agricultural goods could be affected by the seasons, and clothing and combustibles could also be more expensive in mid-winter. Operation Torch, the Allied landings in North Africa on 8 November 1942, made imports of oil, sugar and coffee more scarce, so their prices soared on the black market. Similarly, when communications were cut between Normandy and Paris after the Normandy landings of 6 June 1944, the price of butter greatly increased.[119]

Prices were much higher in the big cities and with increasing distance from the place of production. In December 1942, a kilogram of potatoes sold on the black market for between 4 and 6 francs in Angers, 10 to 15 francs in Lyon, and 25 to 50 francs in Marseille. The risk level from law enforcement was also a factor in prices.[118]

In general, agricultural products sold on the grey market or between friends were 1.5 to three times the official prices. On the black market it was closer to three to five times. Prices on the agricultural black market rose faster at first than the official rate before stagnating in 1943 and 1944 because consumers had less and less disposable income.[118]

Industrial products on the black market were much higher than the official prices, reportedly five to ten times higher. For example, in the spring of 1943 in the Montpellier area, a pair of shoes was worth around 4000 francs on the black market, while the legal price was 250 to 300 francs, and a man's work shirt sold for 500 francs versus an official price of 100 to 150 francs[120]

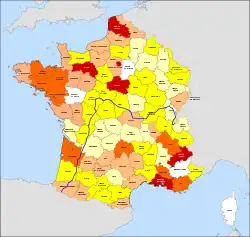

Geographic distribution

(# of fines per 1000 consumers)

Statistics on fines imposed for economic infractions suggest certain geographic traits of the black market. At the level of the départements, agricultural goods often flowed to the préfectures or administrative seats of the département. Between départements, the underground networks often formed circuits between areas with complementary production, whether industrial or agricultural. At the national scale, producer regions linked to big cities like Paris or Lyon.[121]

Western agricultural regions such as Brittany and Normandy, which were reachable from Paris, supplied the capital with meat and other agricultural products. The extent of this flow was such that rations in the producing regions were greatly reduced. In 1942, the meat ration in the Calvados was one of the smallest in France at 90 grams[122] while, according to the préfet, underground slaughterhouses appeared in stables, kitchens, basements, sheds or garages.[122] Low-income families without ties to farmer producers suffered especially from this shortage.[121]

The Paris basin was an important regional hub of the agricultural black market: cereals from Beauce and Vexin, vegetables from the Val de Loire, and meat from Sologne or Morvan were sucked into the underground networks to feed Paris. The agricultural départements near Lyon, such as Saône-et-Loire or Haute-Savoie, and near Marseille, like Ardèche, played similar roles.[123]

Fraud in industry was particularly important in regions with the highest production of consumer goods. For textiles in the metropolis of Lille-Roubaix-Tourcoing, tanning in the Millau region, and hosiery in Troyes and clockwork in Franche-Comté, inspectors found that between half and two thirds of all businesses were in violation of the law.[121]

Paris was the centre of gravity of the black market; transactions there took place essentially everywhere, in hotel rooms, on the street, and in railway stations and the Paris Metro. An active market in textiles operated at Porte de Clignancourt and bicycle tires sold for 1,000 francs at a flea market in Saint-Ouen.[124] Other big cities that were poorly supplied through legal channels, such as Bordeaux or Marseille, were also active centres of the black market. In Marseille, it was particularly omnipresent in the Old Port of Marseille and Le Panier. The mafia, led by Paul Carbone and François Spirito, organized black market trafficking in league with the occupiers.[125] As at the beginning of the occupation, the black market remained important in the vacation spots of the rich: Nice, Deauville, Biarritz, and Megève.[126] Departments bisected by the line of demarcation, such as Indre-et-Loire, Cher or Saône-et-Loire, whose urban and industrial centres fell in the occupied zone and were separated from their natural hinterlands, also saw large-scale inter-zone trafficking on a regional and national level, usually based on bribes to German guards.[121]

The Belgian border had an active export market in contraband, because foodstuffs were even more expensive in Belgium than in France. Belgian cyclists travelled as far as the Somme or Aisne to resupply. The borders with Spain and Switzerland were somewhat better guarded[127] but in Biarritz and all of the Basses-Pyrénées, cattle were smuggled into Spain, where meat was extremely scarce. Smugglers also imported watches from Switzerland.[128]

Beneficiaries

In current public opinion and memory, merchants were war profiteers who enriched themselves on the black market. After the war, those suspected of profiteering continued to be called les BOF (butter, eggs, cheese)[129][128] In fact, retail commerce suffered less than any other economic sector under the occupation, with its share of national revenue jumping from 16% in 1938 to 24.5% in 1946, while the number of sellers increased.[130]

The extent to which anyone got rich in the back market varied a great deal and was based on their position in the network: those furthest upstream and closest to the producer made the biggest profits. Middlemen, brokers, merchants and wholesalers set conditions for retailers, often demanding kickbacks and accumulating profits. For example, the principal supplier of flour in the Paris region systematically demanded payments from almost 200 bakers.[131] In Paris, a June 1942 inspection found that of 100 tonnes of carrots delivered from Seine-et-Oise, only 18 ever reached their official destination at Les Halles. The rest was almost entirely sold on the black market to wholesalers for high prices, then resold to retailers.[132]

When small shopkeepers did not have a personal supply source, it was more true that they were subjected to the black market than that they profited from it. Some still managed however to create ties with farmer producers and short-circuit official networks, like the grocer from the 5th arrondissement of Paris who was able to build up his stock and make a net profit of 100,000 francs in 1942. Another grocer in Surgères in less than a year came to run an underground network that supplied food to Bordeaux, then also Paris and Lyon. The Contrôle économique called him a "great brewer of shady deals affiliated with a whole band of gangsters".[61]

In industry, middlemen also made the most profit. Kickback amounts got bigger and bigger and became systemic. For industrial enterprises, the black market was less profitable than working for the occupiers, except for certain sectors like the textile industry in Lille-Roubaix-Tourcoing, where some businesses manufactured illegal products like electric heaters.[116]

Some indices, like the increase in bank deposits and savings, show farmers becoming more affluent, but the benefits varied by sector and scale. The largest profits were made in wine production, cattle and dairy products. Profits were largest for the owners of larger businesses, who could most easily integrate into the black market networks. For small growers, who consumed a good part of their production themselves, the black market did little but partially compensate them for the difficulties caused by the scarcities of the time.[116]

Among those who profited from the black market, on their own scale, were also the last intermediaries of the networks, who carried out the final stage of delivery. The Paris police arrested people every day who were transporting meat, fruit, vegetables, tobacco or coffee in suitcases, on foot, bicycles or wheelbarrows, for example between the train stations and the addresses of their customers.[133] They were generally from the most modest of social classes and earned extra money this way. This fragmentation of the supply chain allowed the larger traffickers to avoid arrest.[116]

Patriotism (spring 1943-summer 1944)

Beginning in 1943, the black market took on a patriotic coloration, notably because the Germans changed their strategy as to the black market and French collaborators now enforced the regulations against it, The Resistance spread the word about the "patriotic black market".[134]

Enforcement for the occupiers

Economic pillage and the end of the German black market

At the end of 1943, the Germans changed their strategy.[135] In an ordinance dated 2 April 1943, Hermann Göring abandoned the methods of pillage he had adopted at the beginning of the war. He abolished the black market and closed the bureaux d'achat in all occupied territories. After the war Jean de Sailly and René Bousquet presented this decision as a victory of the Vichy authorities. This was not the case, however. Berlin simply put into place more efficient exploitation for all of its occupied territories.[136][137] Starting in 1942, the Germans moved to a total war strategy, in which French businesses were to provide more food and industrial products and German requisitions increased considerably.[138]

For cereals, France was to deliver 714,000 tonnes in 1942–1943, or 17% of its production, versus 485,000 tonnes in 1941-1942 (12%). Meat deliveries directly to the occupier went from 140000 tonnes (15%) in 1941–1942 to 227,000 tonnes in 1942–1943, a quarter of total national production.[136] Occupied France became one of the principal agricultural suppliers of Germany: in 1942–1943, it supplied all of the bread cereals imported into Germany. As French industrial production collapsed, Germany confiscated 30% to 40% and considerably more in some sectors. In ferrous metallurgy and electrometallurgy, occupier requisitions reached two thirds of total production. In 1943, 76% of locomotives, 92% of trucks and 99% of the cement produced in France was delivered to Germany,[139] and payments to Germany were a third of national revenue, versus 20% in 1941 and 1942.[140] At the beginning of 1944, nearly 2.6 million workers, a third of the total workforce, worked directly or indirectly for Germany, whether in Germany itself (prisoners, conscripted civilians) or in France.[139]

In this context, the black market became counter-productive for the occupiers, since they could buy the same products at a lower price and because they had to leave raw materials for French businesses so that they could produce.[136] In March–April 1943, the Germans closed their bureaux d'achats and the Sipo-SD branch of the SS, directed starting September 1943 by Helmut Knochen, oversaw enforcement of the German prohibition of the black market.[141][138]

Still, the employees and hommes de main of these bureaus were not necessarily laid off. Bureau Otto was reoriented to prospecting missions in Spain. The rue Lauriston gang known as the French Gestapo, which had been directed by Henri Lafont and Pierre Bonny under the Sipo-SD, tracked resistance fighters.[138]

The former "kings of the black market", who had enjoyed the protection of the occupiers, were in trouble. Starting in the fall of 1943, Mandel Szkolnikoff and Joseph Joanovici had problems with the Germans. They put their protections into play, paid for their freedom and reinvented themselves, Szkolnikoff in real estate and Joanovici in arms trafficking for the Resistance.[136] On the margins, despite this new policy, some German services continued their buying, and authorities intervened in certain dossiers to protect offenders.[136]

Countermeasures and collaboration

In 1943–1944, the Germans asked Vichy to better suppress the black market, thereafter seen by the occupiers as a way for the French to avoid their economic obligations to Germany. The Germans ceaselessly asked Max Bonnafous, minister of Agriculture and Supply, and René Bousquet, secretary general of the police, as well as Jean de Sailly, chief of the DGCE, for tougher enforcement. It was blackmail: to have any hope of smaller German requisitions, Vichy had to eliminate the black market.[142]

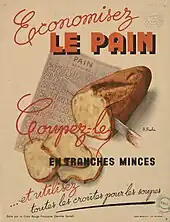

Pierre Laval agreed to play the blackmail game, by launching in the spring of 1943 a widespread propaganda campaign using posters and a comic book. On 8 June 1943, he had the anti-black market legislation modified to permit more a robust enforcement. At a meeting at which he presided on 7 July 1943, René Bousquet emphasized the need for the DGCE to get results.[1][81]

The DGCE increased enforcement and in 1943, a record year, issued more than 300,000 citations for economic infractions.[81][143] Starting in the spring of 1943, it engaged in true police cooperation with the occupiers. "The convergence of diverse interests in opposition to controls – consumers, shopkeepers, producers, farmers, and even unions – was notable for its breadth and its impact," wrote historian Kenneth Mouré in 2022.[144] The Free France intelligence service in London, the BCRA, worried about this policy, seeing it as leading primarily to operations against the Resistance. Investigations and joint operations with the German police were carried out at roadblocks or on visits to farms. In terms of the DGCE's image, this very visible collaboration had a disastrous effect.[1][81][114]

In sum, the Contrôle des prix policed transactions, but its effectiveness was very limited. Enforcement against small daily transactions was less accepted as the needs of consumers became more and more egregious. The hierarchy measured the effectiveness of its agents by the number of citations they issued, a perverse incentive to annoy and alienate the population, whose support would have been useful against large-scale transactions. In the end, the price control policy primarily benefited the occupier.[79]

Milice vs the black market

From its creation, the Milice, created by the law of 30 January 1943, had amongst its primary missions combatting the black market. It rapidly became an instrument of enforcement, despite the disapproval of DGCE Jean de Sailly. Miliciens organized requisitions and seized food, for example from farmers near Toulouse in the summer of 1943, purportedly for redistribution to poor families.[145]

These food distributions were orchestrated and accompanied by the distribution of flyers for propaganda purposes, but did not gain the loyalty of the population, which distrusted this supplementary police force and its brutal methods. The requisitions and confiscations were often illegal and the Milice invented sanctions, such as for the shopkeeper in Bletterans in the Jura on whom the Milice on 29 February 1944 imposed a fine of 100,000 francs because he sold beans for more than the set rate.[146]

Members of the milice kept some of what they confiscated for themselves; in some cases they participated in the black market themselves, for example in July 1944 with 2,696 kilos of sugar seized from a grocer in the village of Les Mages in the Gard.[146] Few of them were sanctioned. In all, the lawless actions of the Milice made the population despise it and reinforced the perception that opposing them by buying or selling on the black market was patriotic.

Fraud and Resistance

Resistance encouragement

Until 1943, the Resistance, which was mostly urban, tended to condemn the black market. However 1943 was a turning point and the Resistance began to take advantage of the widespread anti-Vichy sentiment in the countryside and wrote and distributed more and more leaflets geared to farmers, as statistics show in Franche-Comté or Cher[147]

This Resistance propaganda addressed to rural France was particularly effective when in November 1942, all of France was occupied, and in May 1943, when Laval eliminated the exemption from the Service du travail obligatoire for agricultural workers. The Resistance built on this rural discontent by denouncing Vichy's agricultural policy and legitimizing illegal rural practices. The leaflets say it all: "The Vichy goons are checking, counting and recounting your chickens, your rabbits, your eggs... More and more people are being searched on the farm... You're being bullied, hounded, and baited like in the days of the feudal overlords... Get rid of the Vichy inquisitors!"[147] Starting in 1943, the Resistance legitimized diverting agricultural products to the black market, calling it "a patriotic duty". As a tract said: "Farmer friends, to beat Hitler quickly, we must not surrender French harvests. Refusing to do so is patriotism, is helping to liberate France".[147]

In the regions where the various maquis developed, they began to practice a system of "patriotic taxation". Georges Guingouin of the Maquis du Limousin had maximum prices posted beyond which the offender was essentially punished. This "patriotic taxation" spread to other maquis in Haute-Savoie, the Jura and Brittany with the support of Free France. Thus, the Resistance sometimes managed to impose its prices, and therefore its power, to the detriment of Vichy. It also condemned and sometimes took down the maquis who committed acts of banditry,[148][149]

Blaming the Resistance

Vichy returned the accusation. While silent on the size of German requisitions, Vichy propaganda accused the resistance of responsibility for the shortages that aggravated considerably at the end of the Occupation. The Resistance member was presented as a black market trafficker. It is true that the underground, in order to survive, needed to use tickets and ration cards that were either falsified or stolen.[148]

Vichy also instrumentalized the supply problems of the Maquis, a vital issue to which they devoted a lot of energy. Maquis groups organized commando operations against the stocks of Vichy services and also against farmers. Some groups, under the pretext of patriotism, pillaged the countryside, such as the maquis Lecoz in Indre-et-Loire in the summer of 1944. Speeches and films from Vichy used these attacks to identify the Resistance with banditry, and painted a portrait of maquisards profiting from the black market.[148]

On the other hand, the Resistance and Free France broadcasts on the BBC legitimized small transactions necessary to resupply, distinguishing them from the true black market and threatening traffickers with revenge after the coming Liberation.

End of the occupation

In the last months of the occupation, Vichy agencies were no longer able to organize the food supply. The position of the agents of the Contrôle économique became more and more difficult. They scrupulously avoided checking Resistance members and sometimes interrupted investigations in progress when they were involved. Jean de Sailly tried to keep the DGCE out of an overly pronounced collaboration. Starting in the fall of 1943, the reports his agency sent to the Germans omitted the names and addresses of those cited. To escape the authority of the Milice and of its head Joseph Darnand, Jean de Sailly arranged for his agency to no longer be tasked with economic police missions.[81][151]

_Aux_Femmes_de_Paris%252C_1990.54.jpg.webp)

As German requisitions grew, shortages became more and more severe, rations became even smaller, and the quantities actually legal available were less than the designated ration amounts. In December 1943, in Tournissan in Aude, schoolchildren no longer had milk: "The milkman brings 20 to 30 litres every two days whereas it would take at least 100 litres to serve all those with cards. Also, children over 6 have not had a drop of milk since August".[112] Family food packages were harder to get due to transportation problems, and prices on the black market exploded. City residents once more began to ride bicycles into the country to buy food, especially around Paris, but some rural areas were no longer accessible or were themselves stripped of resources.[151]

The obsession with supply was such that it sometimes relegated the bombings and the war itself to the background. The black market was seen as responsible for the increase in prices but also as indispensable to survival. The situation exacerbated social tensions, notably between cities and rural areas. Country dwellers were seen by many urban residents as privileged. In the countryside, insecurity mounted. Thefts multiplied, farms were attacked and pillaged.[151] In Maine-et-Loire, in June and July 1944 just before the Libération, which was in August in that département, 25 farms were attacked. Of these 17 attacks were political, intended to punish an enrichment that was thought excessive, while the other eight seem to have been simple extortion.[152] Many French believed that the Liberation of France, by eliminating German requisitions, would also bring an end to rationing and the black market.[151][153]

After the Liberation (1944-1949)

After the Libération, many hopes were dashed. Many French people felt that the purge relating to the black market was not severe enough, especially as supply difficulties persisted and, as a result, the black market continued.[154][153]

Épuration and illicit profits

Pursuit and punishment

Punishment for black marketeers was part of the épuration légale (purge of collaborators), in response to strong public demand.[99][155] Vigilante justice killed approximately 10,000 French as the war came to an end.[156] In Brittany, half of the reports to the authorities concerned the black-market or economic collaboration, while only 10% corresponded to strictly political collaboration and 2% to "sentimental collaboration", i.e. women accused of sexual relations with the enemy. Shopkeepers were over-represented among the suspects. Of these, 39% sold food and 26% other products.[157]

Public opinion decried the war profiteer, a figure of the public imagination that reactivated a social stereotype from the First World War, except that in 1944 the war profiteer was not only seen as lacking in solidarity, but also as a "bad Frenchman" who shamed his country.[158][159][99]

As the first metropolitan territory liberated in October 1943, Corsica served as a trial, but the official policy of confiscation of illicit profits was a failure there.[155] However, the French government announced plans to confiscate mines in the north of France and the Renault plant near Paris.[160] In the aftermath of the liberation, the local Liberation Committees and the departmental Liberation Committees carried out their own purges, often summary executions.[159][161] These were not coordinated with the Contrôle economic, which many resistance fighters identified with Vichy.[155] Still, confiscation of illicit profits was slow and incomplete, except for the most notorious black marketeers.

The patriotic militias were officially abolished on 28 October 1944, but some FFIs continued their activity. In January 1945 in Bourges, they confiscated goods from black market traffickers and redistributed them to the population.[159] Until the beginning of 1945, organized gangs also held farmers for ransom in the Savoie and Haute-Loire departments.[159]

Confiscation of illicit profits

Confiscation of property from black market traffickers was first formulated in 1943 in Algiers, then formalized by the National Council of the Resistance in March 1944. On 18 October 1944, an ordinance created the Departmental Committees for the Confiscation of Illicit Profits,[155][162] which began their work in early 1945. Each CDCPI had four departmental directors of tax administration and economic control and three representatives from the Resistance. They investigated activities between 1 September 1939 and 31 December 1944. There was some continuity with Vichy, since offenders were sentenced for violating Vichy legislation or for Economic Control cases. The CDCPI could confiscate illicit profits and impose a fine of up to three times the amount declared illegal.[163][162]

A vast operation to exchange new French francs for old was planned in the spring of 1945 to reduce the money supply.[164] Minister of the economy Pierre Mendès France proposed to freeze the monetary assets of private individuals over 5000 francs, then gradually return the funds over the reconstruction period. This also would have enabled investigations of unexplained wealth and confiscation of illicit profits. However Charles de Gaulle and the French provisional government believed Mendès France's proposal would be too unpopular. Mendès France resigned and the banknotes were exchanged without impediment in June 1945.[163][165]

The CDCPIs issued a total of 124,000 citations, including more than 20,000 in the department of the Seine, 5,000 in the Nord department, 4,500 in Rhône, and more than 2,000 in Seine-et-Marne, Pas-de-Calais, Isère, the Gironde, Côtes-d'Armor, Loire-Inférieure, Alpes-Maritimes, Finistère and Bouches-du-Rhône. In all other departments, the number of citations was less than 2,000.[163][166]

At the end of 1949, penalties, including confiscations and fines amounted to 150 billion francs.[163] After a year of operation, the CDCPI agencies of Maine-et-Loire, Ille-et-Vilaine and Haute-Savoie had only investigated half the cases.[167] In the glove manufacturing industry, almost 90% of the citations were in 1946 for Saint-Junien and almost half in 1946 and 1947 in Grenoble.[168] The task was long, difficult and slow, and the last files were not finally closed until 1950. The obstacles were numerous: the difficulty in precisely measuring illicit profits given the clandestine nature of the transactions, the frequent appeals, and, more fundamentally, the moral ambivalence of the defendants, since the black market had also been at the service of the Resistance. The CDCPI dealt with behavior ranging from the pursuit of enrichment to a will to survive.[163][155][164][162]

"State policies and enforcement practices alienated a remarkably wide range of producers, consumers and intermediaries whose interests often diverge, and ... insufficient food supply catalysed popular opposition to controls, wrote Moure in 2022. The economic purge of the black market was not accompanied by a judicial purge, since black market trade between French nationals was not illegal or considered treasonous, unlike doing business with the occupying forces.[155] Only the most notorious traffickers were tried, and usually for collaborating with the enemy. The primary members of the rue Lauriston gang were sentenced to death in December 1944. In June 1944 Mandel Szkolnikoff, who had fled to Spain, was murdered.[169][60] Joseph Joanovici claimed to have been a member of the resistance and was only fined and belatedly sentenced in July 1949 to five years' imprisonment. Many small traffickers were not punished at all, which fueled resentment as shortages persisted for several years.[163][60][170]

Continued black market operations

Continued trafficking

After the liberation, the black market seemed even more widespread than before. In Valence, "never had economic regulations been so poorly respected", reported the Contrôle économique and in Jura "the black market was flourishing more than ever". The Bank of France made the same observation: "The black market is experiencing a level of activity, if not prosperity, that has not yet been equalled since these methods began to spread, i.e. since the start of the occupation."[172][173][lower-alpha 5]

Farmers still refused to accept the prices set by the government, which they considered too low to allow them to survive. Black and grey market channels remained active, particularly to supply food to city-dwellers.[172] In the winter of 1945, official rations fell to 1,200 calories a day,[112] and masses of people once more rode their bicycles out of the cities into the villages to find food, in the Manche for example. Shipments of food to city dwellers also resumed. Military personnel used their trucks to transport black market goods and Paris restaurants at the end of 1944 still offered black market menus at prohibitive prices.[172]

More and more people tried to earn money in small-scale trafficking and some of these enterprises were supplied by American military inventories. Allied armies had brought with them their own supplies, and American products, especially chocolate, sugar, cigarettes, sweets and chewing gum were very popular. Despite the bans, some soldiers sold them on their own account. Other supplies were diverted by mafias as they arrived at the ports of Le Havre and Marseille.[172]

Generalized fraud

In all economic activities, desperation was widespread. The US Army reported the food supply in Nice in October 1944 was

"catastrophic... we are now employing all facilities to halt the black market and they no longer can rely on this source of food. Many consumers believed that food supply officials deliberately sabotaged the system to prolong shortages and undermine support for the new regime."[173]

According to the Bank of France, “Statistics are fudged, declarations are falsified... everyone tries to deceive, to trick, to conceal”. Fraud in the various distribution channels slowed down the reconstruction and increased the difficulties of businesses, especially faced with a major labour shortage that resulted in a black market in wages. The black market could therefore appear to be a temporary solution.[174]

In 1945 and 1946, industry and commerce with very little equity created many new sociétés à responsabilité limitée (s.a.r.l.) to capture raw materials and other supplies from official distribution channels and resell them on the black market,[174][175] and in Alsace 50,000 new people joined the textile trade, without experience or premises. Many products escaped official channels and this hindered reconstruction.[174]

Government powerlessness

After the Liberation, the scale of continuing food shortages induced the Provisional Government of the French Republic to maintain the price control and organisational structures established by the Vichy regime, and retain their administrative personnel. On 31 August 1944 the government confirmed Jean de Sailly in his position and only about a hundred DGCE agents (1.5% of the total) were purged for collaboration.[81][176] This policy failed in the court of public opinion however which increasingly objected to "continuity not just in Vichy policies, but in state perseverance with policies that were visibly failing and needed public support to be effective".[177]

For many members of the Resistance, the Contrôle économique was discredited by its role during the Occupation. The French Communist Party and members of the Gaullist Party such as Jacques Debû-Bridel (a member of the National Council of the Resistance and then of the Provisional Consultative Assembly) denounced the continued existence of the Supply and Economic Control bodies and called for them to be purged. During the winter of 1944-1945 more than 300 "hunger marches" against these administrations occurred in Nantes, Lyon and almost every department.[176] They were sometimes organized by the central trade unions (CGT) or the French Confederation of Christian Workers (CFTC), but also by the Women in solidarity (UFF) an organisation stemming from the French Communist Party.[178]

The methods of the Contrôle économique were widely disapproved. In December 1944 three agents dined in a Parisian restaurant, running up a 2690 franc tab at a time when the maximum allowed was 55 francs. The agents then closed the restaurant for a month and fined the owner 50,000 francs. Restaurant owners and customers saw this episode as provocation and personal gain for the agents.[179]