| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌkændɪˈsɑːrtən/ |

| Trade names | Atacand, others |

| Other names | Candesartan cilexetil |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a601033 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 15% (candesartan cilexetil) |

| Metabolism | Candesartan cilexetil: intestinal wall; candesartan: hepatic (CYP2C9) |

| Elimination half-life | 9 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney 33%, faecal 67% |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.132.654 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C24H20N6O3 |

| Molar mass | 440.463 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Candesartan is an angiotensin receptor blocker used mainly for the treatment of high blood pressure and congestive heart failure. Candesartan has a very low maintenance dose. Like Olmesartan, the metabolism of the drug is unusual as it is a cascading prodrug. Candesartan has good bioavailibility and is the most potent by weight of the AT-1 receptor antagonists.

It was patented in 1990 and approved for medical use in 1997.[2]

Medical uses

Hypertension

As with other angiotensin II receptor antagonists, candesartan is indicated for the treatment of hypertension.[3] Candesartan has an additive antihypertensive effect when combined with a diuretic, such as chlorthalidone. It is available in a fixed-combination formulation with a low dose of the thiazide diuretic hydrochlorothiazide. Candesartan/hydrochlorothiazide combination preparations are marketed under various trade names including Atacand Plus, Hytacand, Blopress Plus, Advantec and Ratacand Plus.

Heart failure

In heart failure patients, angiotensin receptor blockers such as candesartan and valsartan may be a suitable option for those who do not tolerate angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor medicines.[4][5] Randomised control trials have shown candesartan reduces heart failure hospitalisations and cardiovascular deaths for patients who have heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF ≤ 40%).[5][6]

Prehypertension

In a four-year randomized controlled trial, candesartan was compared to placebo to see whether it could prevent or postpone the development of full-blown hypertension in people with so-called prehypertension. During the first two years of the trial, half of participants were given candesartan while the other half received placebo; candesartan reduced the risk of developing hypertension by nearly two-thirds during this period. In the last two years of the study, all participants were switched to placebo. By the end of the study, candesartan had significantly reduced the risk of hypertension, by more than 15%. Serious adverse effects were more common among participants receiving placebo than in those given candesartan.[7]

Prevention of atrial fibrillation

In 2005, meta-analysis results showed that angiotensin receptor blockers and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors considerably reduce the risk of atrial fibrillation in patients with coexisting heart failure and systolic left ventricular dysfunction.[8] Specifically, an analysis of the CHARM study showed benefits for Candesartan in reducing new occurrences of atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure and reduced left ventricular function.[9] While these studies have demonstrated a potential additional benefit for candesartan when used in patients with systolic left ventricular dysfunction, additional studies are required to further elucidate the role of candesartan in the prevention of atrial fibrillation in other population groups.

Diabetic retinopathy

Use of antihypertensive drugs has been demonstrated to slow the progression of diabetic retinopathy; the role of candesartan specifically in reducing progression in type 1 and type 2 diabetes is still up for debate.[10][11][12] Results from a 2008 study on patients with type 1 diabetes showed there was no benefit in using candesartan to reduce progression of diabetic retinopathy when compared to placebo.[11] Candesartan has been demonstrated to reverse the severity (cause regression) of mild to moderate diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes.[12] The patient populations investigated in these studies were limited to mostly Caucasians and those younger than 75 years of age, so generalization of these findings to other population groups should be done with caution.[11][12]

Migraine prophylaxis

Candesartan may be helpful in migraine prevention as it has better tolerability and less side effects compared to other first line medications.[13][14] It has been recommended by multiple guidelines for migraine prophylaxis in adults with different levels of recommendations,[15][16][17][18][19] however further studies on larger populations are needed.

Adverse effects

As with other drugs that inhibit the renin–angiotensin system, if candesartan is taken by pregnant women during the second or third trimester, it can cause injury and in some cases, death of the developing fetus. Symptomatic hypotension may occur in people who take candesartan and are volume-depleted or salt-depleted, as can also occur when diuretics are coadministered. Reduction in renal glomerular filtration rate may occur; people with renal artery stenosis may be at higher risk. Hyperkalemia may occur; people who are also taking spironolactone or eplerenone may be at higher risk.[3]

Anemia may occur, due to inhibition of the renin–angiotensin system.[20]

As with other angiotensin receptor blockers, candesartan can rarely cause severe liver injury.[21]

Chemistry and pharmacokinetics

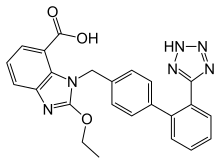

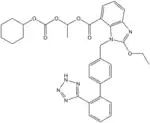

Candesartan is marketed as the cyclohexyl 1-hydroxyethyl carbonate (cilexetil) ester, known as candesartan cilexetil. Candesartan cilexetil is metabolised completely by esterases in the intestinal wall during absorption to the active candesartan moiety. The first step that occurs in the cascading pro-drug mechanism of candesartan is that the carbonate gets hydrolyzed, releasing carbon dioxide. The metabolite at this step is cyclohexanol, and this is a relatively non-toxic compound which is advantageous to the design of the drug. The other aspect of the cascading prodrug is the O-CH-CH3 molecule which becomes converted into acetic acid, which is another product from the cascading side reaction. Similar to the insight from cyclohexanol, the metabolite of acetic acid relatively is non-toxic and thus less of a hazard if produced as the drug takes pharmacologic action.

The use of a prodrug form increases the bioavailability of candesartan. Despite this, absolute bioavailability is relatively poor at 15% (candesartan cilexetil tablets) to 40% (candesartan cilexetil solution). Its IC50 is 15 μg/kg. Candesartan is not administered in its active form because the administration of the pro-drug would require greater doses and has an unfavorable adverse event profile.

Research

Candesartan is being investigated for its neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory properties. In an early Alzheimer's disease mouse model, candesartan significantly reduced amyloid burden and inflammation[22] and is being examined as a potential treatment for early Alzheimer's.[23] Rat models show that candesartan may have neuroprotective benefits that ameliorate certain central mechanisms of ageing and senescence.[24] Candesartan has also demonstrated some possible therapeutic anti-stress and anti-anxiety applications.[25] In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study, candesartan induced regression of left ventricular hypertrophy, and improved LV function and exercise tolerance with no side effects in patients with non obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.[26]

History

The compound known as TCV-116 (candesartan) was studied by Japanese scientists using standard laboratory rats. Animal studies were published showing the effectiveness of the compound in 1992–1993, with a pilot study on humans published in the summer of 1993.[27][28]

Names

The prodrug candesartan cilexetil is marketed by AstraZeneca and Takeda Pharmaceuticals, commonly under the trade names Blopress, Atacand, Amias, and Ratacand. It is available in generic form.

References

- ↑ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ↑ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 471. ISBN 9783527607495.

- 1 2 "Candesartan label" (PDF). FDA. February 2016. For label updates see FDA index page for IND 020838

- ↑ Cohn JN, Tognoni G (December 2001). "A randomized trial of the angiotensin-receptor blocker valsartan in chronic heart failure". The New England Journal of Medicine. 345 (23): 1667–1675. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa010713. PMID 11759645.

- 1 2 Granger CB, McMurray JJ, Yusuf S, Held P, Michelson EL, Olofsson B, et al. (CHARM Investigators and Committees) (September 2003). "Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function intolerant to angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: the CHARM-Alternative trial". Lancet. 362 (9386): 772–776. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14284-5. PMID 13678870. S2CID 5650345.

- ↑ Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Granger CB, Held P, McMurray JJ, Michelson EL, et al. (September 2003). "Effects of candesartan on mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic heart failure: the CHARM-Overall programme". Lancet. 362 (9386): 759–766. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14282-1. PMID 13678868. S2CID 15011437.

- ↑ Julius S, Nesbitt SD, Egan BM, Weber MA, Michelson EL, Kaciroti N, et al. (April 2006). "Feasibility of treating prehypertension with an angiotensin-receptor blocker". The New England Journal of Medicine. 354 (16): 1685–1697. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa060838. PMID 16537662.

- ↑ Healey JS, Baranchuk A, Crystal E, Morillo CA, Garfinkle M, Yusuf S, Connolly SJ (June 2005). "Prevention of atrial fibrillation with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers: a meta-analysis". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 45 (11): 1832–1839. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2004.11.070. PMID 15936615.

- ↑ Ducharme A, Swedberg K, Pfeffer MA, Cohen-Solal A, Granger CB, Maggioni AP, et al. (May 2006). "Prevention of atrial fibrillation in patients with symptomatic chronic heart failure by candesartan in the Candesartan in Heart failure: assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM) program". American Heart Journal. 151 (5): 985–991. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2005.06.036. PMID 16644318.

- ↑ Elkjaer AS, Lynge SK, Grauslund J (June 2020). "Evidence and indications for systemic treatment in diabetic retinopathy: a systematic review". Acta Ophthalmologica. 98 (4): 329–336. doi:10.1111/aos.14377. PMID 32100477. S2CID 211523341.

- 1 2 3 Chaturvedi N, Porta M, Klein R, Orchard T, Fuller J, Parving HH, et al. (October 2008). "Effect of candesartan on prevention (DIRECT-Prevent 1) and progression (DIRECT-Protect 1) of retinopathy in type 1 diabetes: randomised, placebo-controlled trials". Lancet. 372 (9647): 1394–1402. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61412-9. PMID 18823656. S2CID 20796943.

- 1 2 3 Sjølie AK, Klein R, Porta M, Orchard T, Fuller J, Parving HH, et al. (October 2008). "Effect of candesartan on progression and regression of retinopathy in type 2 diabetes (DIRECT-Protect 2): a randomised placebo-controlled trial". Lancet. 372 (9647): 1385–1393. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61411-7. PMID 18823658. S2CID 15210734.

- ↑ Stovner LJ, Linde M, Gravdahl GB, Tronvik E, Aamodt AH, Sand T, Hagen K (June 2014). "A comparative study of candesartan versus propranolol for migraine prophylaxis: A randomised, triple-blind, placebo-controlled, double cross-over study". Cephalalgia. 34 (7): 523–532. doi:10.1177/0333102413515348. PMID 24335848. S2CID 24678271.

- ↑ Sánchez-Rodríguez C, Sierra Á, Planchuelo-Gómez Á, Martínez-Pías E, Guerrero ÁL, García-Azorín D (February 2021). "Real world effectiveness and tolerability of candesartan in the treatment of migraine: a retrospective cohort study". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 3846. Bibcode:2021NatSR..11.3846S. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-83508-2. PMC 7884682. PMID 33589682.

- ↑ "Therapeutic Guidelines | Therapeutic Guidelines". tgldcdp.tg.org.au. Retrieved 2023-05-12.

- ↑ Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, Dodick DW, Argoff C, Ashman E (April 2012). "Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society". Neurology. 78 (17): 1337–1345. doi:10.1212/wnl.0b013e3182535d20. PMC 3335452. PMID 22529202. S2CID 8597108.

- ↑ Tzankova V, Becker WJ, Chan TL (February 2023). "Pharmacologic prevention of migraine". CMAJ. 195 (5): E187–E192. doi:10.1503/cmaj.221607. PMC 9904820. PMID 36746481. S2CID 256598489.

- ↑ "Guidelines". Canadian Headache Society. Retrieved 2023-05-12.

- ↑ Evers S, Afra J, Frese A, Goadsby PJ, Linde M, May A, Sándor PS (September 2009). "EFNS guideline on the drug treatment of migraine--revised report of an EFNS task force". European Journal of Neurology. 16 (9): 968–981. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02748.x. PMID 19708964. S2CID 9204782.

- ↑ Cheungpasitporn W, Thongprayoon C, Chiasakul T, Korpaisarn S, Erickson SB (November 2015). "Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors linked to anemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis". QJM. 108 (11): 879–884. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcv049. PMID 25697787.

- ↑ Patti R, Sinha A, Sharma S, Yoon TS, Kupfer Y (May 2019). "Losartan-induced Severe Hepatic Injury: A Case Report and Literature Review". Cureus. 11 (5): e4769. doi:10.7759/cureus.4769. PMC 6663042. PMID 31363450.

- ↑ Torika N, Asraf K, Apte RN, Fleisher-Berkovich S (March 2018). "Candesartan ameliorates brain inflammation associated with Alzheimer's disease". CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 24 (3): 231–242. doi:10.1111/cns.12802. PMC 6489976. PMID 29365370.

- ↑ Saavedra JM (March 2016). "Evidence to Consider Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers for the Treatment of Early Alzheimer's Disease". Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology. 36 (2): 259–279. doi:10.1007/s10571-015-0327-y. PMID 26993513. S2CID 254384149.

- ↑ Elkahloun AG, Saavedra JM (March 2020). "Candesartan Neuroprotection in Rat Primary Neurons Negatively Correlates with Aging and Senescence: a Transcriptomic Analysis". Molecular Neurobiology. 57 (3): 1656–1673. doi:10.1007/s12035-019-01800-9. PMC 7062590. PMID 31811565.

- ↑ Saavedra JM, Armando I, Bregonzio C, Juorio A, Macova M, Pavel J, Sanchez-Lemus E (June 2006). "A centrally acting, anxiolytic angiotensin II AT1 receptor antagonist prevents the isolation stress-induced decrease in cortical CRF1 receptor and benzodiazepine binding". Neuropsychopharmacology. 31 (6): 1123–1134. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300921. PMID 16205776. S2CID 23912388.

- ↑ Penicka M, Gregor P, Kerekes R, Marek D, Curila K, Krupicka J (January 2009). "The effects of candesartan on left ventricular hypertrophy and function in nonobstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a pilot, randomized study". The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics. 11 (1): 35–41. doi:10.2353/jmoldx.2009.080082. PMC 2607563. PMID 19074594.

- ↑ Mizuno K, Niimura S, Tani M, Saito I, Sanada H, Takahashi M, et al. (1992). "Hypotensive activity of TCV-116, a newly developed angiotensin II receptor antagonist, in spontaneously hypertensive rats". Life Sciences. 51 (20): PL183–PL187. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(92)90627-2. PMID 1435062.

- ↑ Ogihara T, Higashimori K, Masuo K, Mikami H (Jul–Aug 1993). "Pilot study of a new angiotensin II receptor antagonist, TCV-116: effects of a single oral dose on blood pressure in patients with essential hypertension". Clinical Therapeutics. 15 (4): 684–691. PMID 8221818.