| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Presidential election | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

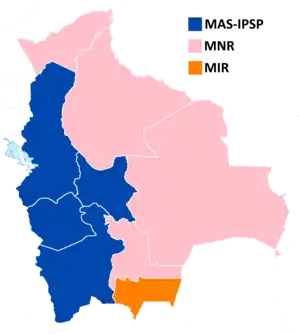

.png.webp) Results by province | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Party performance by department | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|---|

|

|

General elections were held in Bolivia on 30 June 2002.[1] As no candidate for the presidency received over 50% of the vote, the National Congress was required to elect a President. Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada was elected with 84 votes to the 43 received by Evo Morales.

Background

Although Bolivia has had a long history of political instability since independence in 1825, the election in 2002 marked Bolivia's fifth consecutive democratic election.[2] The most recent uninterrupted period of democratic rule began in 1982 as Bolivia developed a unitary political system, with nine departments, divided into 22 provinces and 314 municipalities.[3] At this time, a competitive party system developed around three major parties—the center-right MNR and ADN, and the center-left MIR. In 1989, two populist parties emerged to compete with the three established parties: the left-wing Conciencia de Patria (Condepa) and the right-wing Union Civica Solidaridad (UCS). While the major axis of competition remained along the three established parties, the populist parties combined to capture a third of the popular vote in 1997.[3]

In April 2000, major conflicts over the privatization of water infrastructure in Cochabamba led to violent protests. During that same time, the ADN government moved to rid the country of coca farms. These two events majorly contributed to the increase in support for then Senator Evo Morales and the widespread dissatisfaction with the ADN government. The general dissatisfaction of rural populations in Bolivia increased to the extent that large indigenous protests in La Paz the week before the election pushed for a constituent assembly to better represent the rural and indigenous social groups in the constitution.[2] Because of the threat these marches posed to the stability of the election, the government agreed to hold a Special Session considering constitutional reforms, after the election.[4]

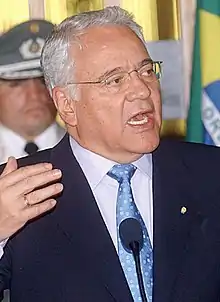

After the deaths of their respective party leaders, Condepa and UCS lost significant power and popular support. By the 2002 election, two other populist parties emerged to take their place, Manfred Reyes Villa’s Nueva Fuerza Republicana (NFR) and Evo Morales' Movement for Socialism (MAS). The election revolved around these two ‘outsider’ candidates and the MNR’s established candidate, Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada (Goni), a high profile American-educated politician who had previously served from 1993 to 1997.[2]

Parties and candidates

11 parties total qualified for the election, including some new and nontraditional parties.

MNR-MBL

The MNR-MBL (an alliance between the centrist Revolutionary Nationalist Movement and the center-left Free Bolivia Movement) nominated former president Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada for the presidency. One of the parties that had traditionally held power since the beginning of Bolivian democracy, it had close ties with the country's business elite and had cracked down on coca production in the 90s, hoping to improve relations with the United States.

Sánchez de Lozada's campaign was run by American campaign managers, including James Carville, who used tools typically not seen in Bolivian elections to help their candidate win—focus groups, TV ads, and extensive use of polling among them. These campaign consultants, combined with Sánchez de Lozada's American background (he grew up in America, and attended the University of Chicago) fostered distrust among the Bolivian people, many of whom blamed the US for damaging the coca industry. At the same time, the campaign tactics also helped to bolster their position.

Movement for Socialism

The Movement for Socialism (MAS) was an upstart populist party, led by former coca farmer and union leader Evo Morales. It rose to prominence during the campaign by promising to restore coca production and championing indigenous rights, which had not had much power in the decades leading up to the election (before 2002, indigenous parties never won more than 5% of the vote.[5]) Morales' campaign was given a boost when, shortly before the election, the US ambassador asked Bolivians to vote for anyone but Morales—angering the voters, who felt the US was trying to meddle in their election.[6] The party ultimately beat expectations, coming in second place and setting Morales up as the opposition leader to Sánchez de Lozada.

New Republican Force

The New Republican Force (NRF) was the other traditional political party running in the election, nominating former mayor of Cochabamba Manfred Reyes Villa.[7] Reyes Villa came in a close 3rd, winning about 700 votes fewer than Morales, and formed a governing coalition with Sánchez de Lozada. Later, Sánchez de Lozada was forced to resign when Reyes Villa pulled his support.[8]

MIR-FRI

The MIR-FRI (an alliance between the left wing Revolutionary Left Movement and Revolutionary Left Front parties) nominated former president Jaime Paz Zamora. Zamora's earlier term was relatively successful, but his actions left him vulnerable to attacks similar to those aimed at Sánchez de Lozada—accusations that he hurt coca farmers, and wasn't doing enough for the poor.[9]

Pachakuti Indigenous Movement

The Pachakuti Indigenous Movement, led by Felipe Quispe, was an indigenist and populist left-wing party, running directly against the neoliberal centrism promoted by Sánchez de Lozada and Zamora. Its platform is similar to that of Morales and his MAS, although more extreme, condemning any cooperation with United States anti-coca programs and economic reforms. Quispe came in 5th, with 6.1% of the vote.

Campaign

In the 2002 election there were 11 total parties competing for the vote. For the first time, three established parties (MNR, MIR and UCS) formed a coalition in order to compete with the rising dominance of the populist parties. This demonstrated a significant shift in the electoral environment as the axis of competition shifted from intra-elite competition to competition between the traditional parties and outsider parties.[2]

The strong nationalist and populist surge was partly a backlash against the pro-globalization and neoliberal reforms enacted by Sánchez de Lozada during his earlier term as president, as well as his American background and education. He was seen as overly sympathetic to American and other foreign interests, a perception reinforced when the US ambassador asked Bolivians not to vote for the populist Morales shortly before the election.[6]

Throughout this uninterrupted period of Democracy starting in 1982 the leading parties and fringe parties have stayed roughly the same. In this election there was a sudden shift in the front runners of the race. In this race, one of the previous power house parties, National Democratic Action (ADN), gained less than 4% percent of the vote, while fringe party leaders Evo Morales, and Felipe Quispe moved into 2nd and 5th place.[10]

The period after military rule in Bolivia when citizens were once again put in charge of the government showed a lot of instability in the political sphere. Most political scientists believe that the political state of Bolivia in 1993 was one of havoc, but it was moving towards becoming a more unified democracy. The 2002 campaigns leading up to the election as well as the election results themselves show a different picture. The stratification and instability of the party system has become even more strained than it previously was and constituted one of the most volatile campaign seasons in Bolivian history since independence.[10]

Coca production also played an important role in the election. Sánchez de Lozada had cracked down on illegal coca production during his earlier term as president, which improved Bolivian relations with the United States but hurt many poor and indigenous farmers, who relied on coca as their livelihood. Runner-up Evo Morales, who had come from the indigenous population and represented coca farmers earlier in his life, promised to restore the coca industry and reject American influence—leading to the US ambassador's denunciation of his candidacy, as mentioned above.[11] Nevertheless, the threat was credited with significantly boosting the amount of support Morales received in the election as well.[12][13]

Results

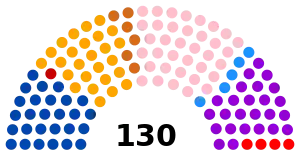

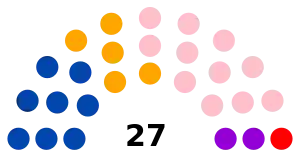

A total of 24 women won seats in the National Congress and four were in the Chamber of Senators following the parliamentary elections.[14]

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Presidential candidate | Votes | % | Seats | |||||

| Chamber | +/– | Senate | +/– | ||||||

| MNR–MBL | Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada | 624,126 | 22.46 | 36 | +5 | 11 | +6 | ||

| Movement for Socialism | Evo Morales | 581,884 | 20.94 | 27 | New | 8 | New | ||

| New Republican Force | Manfred Reyes Villa | 581,163 | 20.91 | 25 | – | 2 | – | ||

| MIR–FRI | Jaime Paz Zamora | 453,375 | 16.32 | 26 | +3 | 5 | –1 | ||

| Pachakuti Indigenous Movement | Felipe Quispe | 169,239 | 6.09 | 6 | New | 0 | New | ||

| UCS–FSB | Jhonny Fernández | 153,210 | 5.51 | 5 | –16 | 0 | –2 | ||

| Nationalist Democratic Action | Ronald MacLean Abaroa | 94,386 | 3.40 | 4 | – | 0 | – | ||

| Freedom and Justice Party | Alberto Costa | 75,522 | 2.72 | 0 | New | 0 | New | ||

| Socialist Party | Rolando Morales | 18,162 | 0.65 | 1 | New | 0 | New | ||

| Citizens' Movement for Change | René Blattmann | 17,405 | 0.63 | 0 | New | 0 | New | ||

| Conscience of Fatherland | Nicolás Valdivia | 10,336 | 0.37 | 0 | –19 | 0 | –3 | ||

| Total | 2,778,808 | 100.00 | 130 | 0 | 27 | 0 | |||

| Valid votes | 2,778,808 | 92.81 | |||||||

| Invalid/blank votes | 215,257 | 7.19 | |||||||

| Total votes | 2,994,065 | 100.00 | |||||||

| Registered voters/turnout | 4,155,055 | 72.06 | |||||||

Aftermath

Although many Bolivians were dissatisfied with the results of the election, the elections were generally competitive and fair.[15] Of the candidates only Reyes Villa made claims of electoral fraud, and these claims were largely taken as griping rather than serious accusations.[15] No candidate won a clear majority, so the newly elected legislature had to choose between the top two candidates. At this point, Sánchez de Lozada openly negotiated with MIR and Villa’s NFR to shore up coalition support, while Morales refused negotiate with other parties. On 25 July, four weeks after the elections, the MNR, MIR, and UCS among other parties formed the "Government of National Responsibility."[16] After a two-month period of negotiations and coalition making, Sánchez de Lozada was officially elected president by Congress on 4 August with 84 of the 127 valid Congressional votes. While the elections were constitutionally legal and democratic, many voters felt unrepresented and were dissatisfied with the domination of the ideologically incoherent coalition. More than 70 percent of the population had not supported Sánchez de Lozada in the electoral vote, and Congress had elected him president through a series of party negotiations.[16]

Inauguration day was met with massive protests by the national confederations of laborers, teachers, medical workers, and peasants. Sánchez de Lozada's precarious position only worsened. Six months into his presidency, the government announced their plan to increase income tax without a proportional increase for those earning the most. La Paz and other urban centers erupted in massive protests. Even the police and other civil society groups rose up against the proposed income tax. Sánchez de Lozada sent in the military to suppress the protests. Outside the palace, the military opened fire and violently ended the confrontation. While the president retracted the proposed income tax, demonstrations, roadblocks, and violent confrontations continued in the following months.[16]

Massive protests and strikes erupted again when Sánchez de Lozada proposed to export gas through Chile. This resulted in the gas conflict, where dozens of civilians were killed in confrontations with the military. Parties began withdrawing their support from the governing coalition, and Goni was forced to resign and leave the country on 18 October 2003. Goni was succeeded by his Vice-President, Carlos Mesa. While in charge Mesa kept his promises made when he came into power, appointing a cabinet of mostly independents, showing great sensitivity toward the indigenous people, and overturning a 1997 decree that gave natural gas rights to the people who extracted it. Mesa was also in the process of reforming elections, allowing for greater public participation in elections, as well as plans for a constituent assembly to consider creating a new constitution.[17] Even though these reforms temporarily quelled unrest, by 2005 protests erupted again and Mesa was forced to resign. In 2005, the populist candidate Evo Morales was elected president.[16]

On December 1, 2023, Manuel Rocha, who at the time of the election served as U.S. Ambassador to Bolivia and was credited with boosting support for Morales with his public speech threatening to cut U.S. aid to Bolivia if Morales were elected, was arrested in Miami, Florida on charges of illegally acting in the interests of the Cuban government.[13]

See also

- Our Brand Is Crisis (2005), a documentary about Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada's second presidential campaign and influence of American political consultants

- Our Brand Is Crisis (2015), a dramatized version of 2005 documentary

References

- ↑ Nohlen, D (2005) Elections in the Americas: A data handbook, Volume II, p133 ISBN 978-0-19-928358-3

- 1 2 3 4 Matthew M. Singer, Kevin M. Morrison (March 2004). "The 2002 presidential and parliamentary elections in Bolivia Department of Political Science". Electoral Studies. 23 (1): 172–182. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2003.09.004.

- 1 2 Van Cott, Donna Lee (2003). "From Exclusion to Inclusion: Bolivias 2002 Elections". Journal of Latin American Studies. 35 (4): 751–775. doi:10.1017/S0022216X03006977.

- ↑ Harding, James (December 4, 2002). "REPORT ON THE ELECTORAL OBSERVATION MISSION GENERAL ELECTIONS IN BOLIVIA - 2002" (PDF). Organization of American States. Retrieved April 2, 2017.

- ↑ Van Cott, Donna Lee (2003-01-01). "From Exclusion to Inclusion: Bolivia's 2002 Elections". Journal of Latin American Studies. 35 (4): 751–775. doi:10.1017/s0022216x03006977. JSTOR 3875831.

- 1 2 Clarin.com. "Polémica en Bolivia con el embajador de EE.UU". www.clarin.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 2017-04-02.

- ↑ Mayorga, René Antonio (2006), "Outsiders and Neopopulism: The Road to Plepiscitary Democracy", The Crisis of Democratic Representation in the Andes, Stanford University Press, p. 164, ISBN 9780804767910

- ↑ Agencies (2003-10-17). "Bolivian president resigns amid chaos". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-04-03.

- ↑ "CIDOB - CIDOB". CIDOB. Retrieved 2017-04-03.

- 1 2 Assies, Willem (2003). "Crisis in Bolivia: Elections in 2002 and their Aftermath" (PDF). University of London Institute of Latin American Studies Research Papers. 56: 4–22 – via University of London.

- ↑ Harding, James (December 4, 2002). "REPORT ON THE ELECTORAL OBSERVATION MISSION GENERAL ELECTIONS IN BOLIVIA - 2002" (PDF). Organization of American States. Retrieved April 2, 2017.

- ↑ Jean Friedman-Rudovsky, Bolivia to Expel US Ambassador, Time, Sept. 11, 2008

- 1 2 Goodman, Joshua; Tucker, Eric (2023-12-03). "Former US ambassador arrested in Florida, accused of serving as an agent of Cuba, AP source says". Associated Press. Retrieved 2023-12-03.

- ↑ "IFES Election Guide | Elections: Bolivia Legislative June 30 2002". Archived from the original on 2017-04-05. Retrieved 2017-04-04.

- 1 2 Assies, Willem; Salman, Ton (2003). "Crisis in Bolivia: The Elections of 2002 and their Aftermath" (PDF). Institute of Latin American Studies. University of London. Retrieved April 28, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 Muñoz-Pogossian, Betilde (2008). Electoral rules and the transformation of Bolivian politics : the rise of Evo Morales. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 156–160.

- ↑ Ribando, Clare (2007). "Bolivia: Political and Economic Developments and Relations with the United States" (PDF). CRS Report for Congress: 1–18 – via Congressional Research Service.