| Atlanta Braves | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Major league affiliations | |||||

| |||||

| Current uniform | |||||

| |||||

| Retired numbers | |||||

| Colors | |||||

| |||||

| Name | |||||

| Other nicknames | |||||

| |||||

| Ballpark | |||||

| Major league titles | |||||

| World Series titles (4) | |||||

| NL Pennants (18) | |||||

| NA Pennants (4) | |||||

| NL East Division titles (18) | |||||

| NL West Division titles (5) | |||||

| Pre-modern World Series (1) | |||||

| Wild card berths (2) | |||||

| Front office | |||||

| Principal owner(s) | Atlanta Braves Holdings, Inc. Traded as: Nasdaq: BATRA (Series A) OTCQB: BATRB (Series B) Nasdaq: BATRK (Series C) Russell 2000 components (BATRA, BATRK)[3] | ||||

| President | Derek Schiller | ||||

| President of baseball operations | Alex Anthopoulos[4] | ||||

| General manager | Alex Anthopoulos[5] | ||||

| Manager | Brian Snitker | ||||

| Mascot(s) | Blooper[1] | ||||

The Atlanta Braves are an American professional baseball team based in the Atlanta metropolitan area. The Braves compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the National League (NL) East division. The Braves were founded in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1871, as the Boston Red Stockings. The club was known by various names until the franchise settled on the Boston Braves in 1912. The Braves are the oldest continuously operating professional sports franchise in North America.[6][lower-alpha 2]

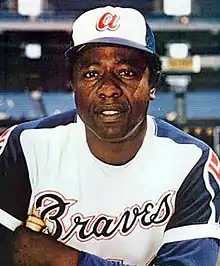

After 81 seasons and one World Series title in Boston, the club moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in 1953. With a roster of star players such as Hank Aaron, Eddie Mathews, and Warren Spahn, the Milwaukee Braves won the World Series in 1957. Despite the team's success, fan attendance declined. The club's owners moved the team to Atlanta, Georgia, in 1966.

The Braves did not find much success in Atlanta until 1991. From 1991 to 2005, the Braves were one of the most successful teams in baseball, winning an unprecedented 14 consecutive division titles,[7][8][9] making an MLB record eight consecutive National League Championship Series appearances, and producing one of the greatest pitching rotations in the history of baseball including Hall of Famers Greg Maddux, John Smoltz, and Tom Glavine.

The Braves are one of the two remaining National League charter franchises that debuted in 1876. The club has won an MLB record 23 divisional titles, 18 National League pennants, and four World Series championships. The Braves are the only Major League Baseball franchise to have won the World Series in three different home cities. At the end of the 2023 season, the Braves' overall win–loss record is 11,025–10,876–154 (.503). Since moving to Atlanta in 1966, the Braves have an overall win–loss record of 4,761–4,388–8 (.520) through the end of 2023.[10]

History

Boston (1871–1952)

1871–1913

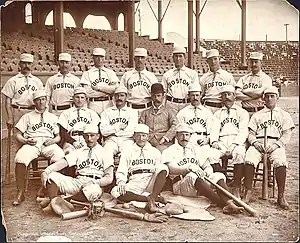

The Cincinnati Red Stockings, established in 1869 as the first openly all-professional baseball team, voted to dissolve after the 1870 season. Player-manager Harry Wright, with brother George and two other Cincinnati players, then went to Boston, Massachusetts, at the invitation of Boston Red Stockings founder Ivers Whitney Adams to form the nucleus of the Boston Red Stockings, a charter member of the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players (NAPBBP).[6]

The original Boston Red Stockings team and its successors can lay claim to being the oldest continuously playing team in American professional sports.[6] The only other team that has been organized as long, the Chicago Cubs, did not play for the two years following the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. Two young players hired away from the Forest City club of Rockford, Illinois, turned out to be the biggest stars during the NAPBBP years: pitcher Al Spalding, founder of Spalding sporting goods, and second baseman Ross Barnes.

Led by the Wright brothers, Barnes, and Spalding, the Red Stockings dominated the National Association, winning four of that league's five championships. The team became one of the National League's charter franchises in 1876, sometimes called the "Red Caps" (as a new Cincinnati Red Stockings club was another charter member).

The Boston Red Caps played in the first game in the history of the National League, on Saturday, April 22, 1876, defeating the Philadelphia Athletics, 6–5.[11][12][13]

Although somewhat stripped of talent in the National League's inaugural year, Boston bounced back to win the 1877 and 1878 pennants. The Red Caps/Beaneaters were one of the league's dominant teams during the 19th century, winning a total of eight pennants. For most of that time, their manager was Frank Selee. Boston came to be called the Beaneaters in 1883 while retaining red as the team color. The 1898 team finished 102–47, a club record for wins that would stand for almost a century. Stars of those 1890s Beaneater teams included the "Heavenly Twins", Hugh Duffy and Tommy McCarthy, as well as "Slidin'" Billy Hamilton.

The team was decimated when the American League's new Boston entry set up shop in 1901. Many of the Beaneaters' stars jumped to the new team, which offered contracts that the Beaneaters' owners did not even bother to match. They only managed one winning season from 1900 to 1913 and lost 100 games five times. In 1907, the Beaneaters temporarily eliminated the last bit of red from their stockings because their manager thought the red dye could cause wounds to become infected, as noted in The Sporting News Baseball Guide in the 1940s.[14]

The American League club's owner, Charles Taylor, wasted little time in adopting Red Sox as his team's first official nickname. Up to that point they had been called by the generic "Americans". Media-driven nickname changes to the Doves in 1907 and the Rustlers in 1911 did nothing to change the National League club's luck. The team became the Braves for the first time before the 1912 season.[14] The president of the club, John M. Ward named the club after the owner, James Gaffney.[14] Gaffney was called one of the "braves" of New York City's political machine, Tammany Hall, which used a Native American chief as their symbol.[14][15]

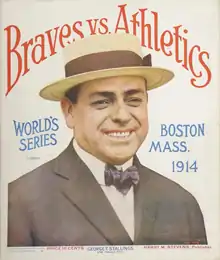

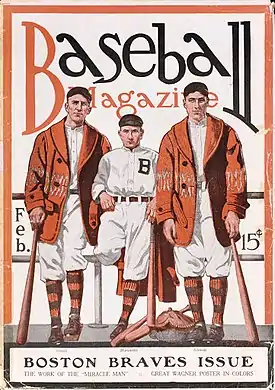

1914: Miracle

Two years later, the Braves put together one of the most memorable seasons in baseball history. After a dismal 4–18 start, the Braves seemed to be on pace for a last-place finish. On July 4, 1914, the Braves lost both games of a doubleheader to the Brooklyn Dodgers. The consecutive losses put their record at 26–40 and the Braves were in last place, 15 games behind the league-leading New York Giants, who had won the previous three league pennants. After a day off, the Braves started to put together a hot streak, and from July 6 through September 5, the Braves went 41–12.[16]

On September 7 and 8, the Braves took two of three games from the New York Giants and moved into first place. The Braves tore through September and early October, closing with 25 wins against six losses, while the Giants went 16–16.[17] They were the only team, under the old eight-team league format, to win a pennant after being in last place on the Fourth of July. They were in last place as late as July 18, but were close to the pack, moving into fourth on July 21 and second place on August 12.[18]

Despite their amazing comeback, the Braves entered the World Series as a heavy underdog to Connie Mack's Philadelphia A's. Nevertheless, the Braves swept the Athletics—the first unqualified sweep in the young history of the modern World Series (the 1907 Series had one tied game) to win the world championship. Meanwhile, Johnny Evers won the Chalmers Award.

The Braves played the World Series (as well as the last few games of the 1914 season) at Fenway Park, since their normal home, the South End Grounds, was too small. However, the Braves' success inspired owner Gaffney to build a modern park, Braves Field, which opened in August 1915. It was the largest park in the majors at the time, with 40,000 seats and a very spacious outfield. The park was novel for its time; public transportation brought fans right to the park.

1915–1953

After contending for most of 1915 and 1916, the Braves only twice posted winning records from 1917 to 1932. The lone highlight of those years came when Judge Emil Fuchs bought the team in 1923 to bring his longtime friend, pitching great Christy Mathewson, back into the game. However, Mathewson died in 1925, leaving Fuchs in control of the team.

Fuchs was committed to building a winner, but the damage from the years prior to his arrival took some time to overcome. The Braves finally managed to be competitive in 1933 and 1934 under manager Bill McKechnie, but Fuchs' revenue was severely depleted due to the Great Depression.

Looking for a way to get more fans and more money, Fuchs worked out a deal with the New York Yankees to acquire Babe Ruth, who had started his career with the Red Sox. Fuchs made Ruth team vice president, and promised him a share of the profits. He was also granted the title of assistant manager, and was to be consulted on all of the Braves' deals. Fuchs even suggested that Ruth, who had long had his heart set on managing, could take over as manager once McKechnie stepped down—perhaps as early as 1936.[19]

At first, it appeared that Ruth was the final piece the team needed in 1935. On opening day, he had a hand in all of the Braves' runs in a 4–2 win over the Giants. However, that proved to be the only time the Braves were over .500 all year. Events went downhill quickly. While Ruth could still hit, he could do little else. He could not run, and his fielding was so terrible that three of the Braves' pitchers threatened to go on strike if Ruth were in the lineup. It soon became obvious that he was vice president and assistant manager in name only and Fuchs' promise of a share of team profits was hot air. In fact, Ruth discovered that Fuchs expected him to invest some of his money in the team.[19]

Seeing a franchise in complete disarray, Ruth retired on June 1—only six days after he clouted what turned out to be the last three home runs of his career. He had wanted to quit as early as May 12, but Fuchs wanted him to hang on so he could play in every National League park.[19] The Braves finished 38–115, the worst season in franchise history. Their .248 winning percentage is the second-worst in the modern era and the second-worst in National League history (ahead of the 1899 Cleveland Spiders with a .130 winning percentage).

Fuchs lost control of the team in August 1935,[19] and the new owners tried to change the team's image by renaming it the Boston Bees. This did little to change the team's fortunes. After five uneven years, a new owner, construction magnate Lou Perini, changed the nickname back to the Braves. He immediately set about rebuilding the team. World War II slowed things down a little, but the team rode the pitching of Warren Spahn to impressive seasons in 1946 and 1947.

In 1948, the team won the pennant, behind the pitching of Spahn and Johnny Sain, who won 39 games between them. The remainder of the rotation was so thin that in September, Boston Post writer Gerald Hern wrote this poem about the pair:[20]

- First we'll use Spahn

- then we'll use Sain

- Then an off day

- followed by rain

- Back will come Spahn

- followed by Sain

- And followed

- we hope

- by two days of rain.

The poem received such a wide audience that the sentiment, usually now paraphrased as "Spahn and Sain and pray for rain", entered the baseball vocabulary.[21] However, in the 1948 season, the Braves had the same overall winning percentage as in games that Spahn and Sain started.

The 1948 World Series, which the Braves lost in six games to the Indians, turned out to be the Braves' last hurrah in Boston. In 1950, Sam Jethroe became the team's first African American player, making his major league debut on April 18. Amid four mediocre seasons, attendance steadily dwindled until, on March 13, 1953, Perini, who had recently bought out his original partners, announced he was moving the team to Milwaukee, where the Braves had their top farm club, the Brewers. Milwaukee had long been a possible target for relocation. Bill Veeck had tried to return his St. Louis Browns there earlier the same year (Milwaukee was the original home of that franchise), but his proposal had been voted down by the other American League owners.

Milwaukee (1953–1965)

Milwaukee went wild over the Braves, drawing a then-NL record 1.8 million fans. The Braves finished 92–62 in their first season in Milwaukee. The success of the relocated team showed that baseball could succeed in new markets, and the Philadelphia Athletics, St. Louis Browns, Brooklyn Dodgers, and New York Giants left their hometowns within the next five years.

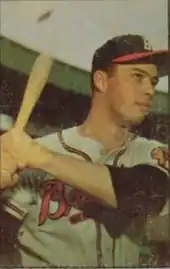

As the 1950s progressed, the reinvigorated Braves became increasingly competitive. Sluggers Eddie Mathews and Hank Aaron drove the offense (they hit a combined 1,226 home runs as Braves, with 850 of those coming while the franchise was in Milwaukee and 863 coming while they were teammates), often aided by another power hitter, Joe Adcock, while Warren Spahn, Lew Burdette, and Bob Buhl anchored the rotation. The 1956 Braves finished second, only one game behind the Brooklyn Dodgers.

In 1957, the Braves celebrated their first pennant in nine years spearheaded by Aaron's MVP season, as he led the National League in both home runs and RBI. Perhaps the most memorable of his 44 round-trippers that season came on September 23, a two-run walk-off home run that gave the Braves a 4–2 victory over the St. Louis Cardinals and clinched the League championship. The team then went on to its first World Series win in over 40 years, defeating the powerful New York Yankees of Berra, Mantle, and Ford in seven games. One-time Yankee Burdette, the Series MVP, threw three complete-game victories against his former team, giving up only two earned runs.

In 1958, the Braves again won the National League pennant and jumped out to a three games to one lead in the World Series against the New York Yankees once more, thanks in part to the strength of Spahn's and Burdette's pitching. But the Yankees stormed back to take the last three games, in large part to World Series MVP Bob Turley's pitching.

The 1959 season saw the Braves finish the season in a tie with the Los Angeles Dodgers, both with 86–68 records. Many residents of Chicago and Milwaukee were hoping for a Sox-Braves Series, as the cities are only about 75 miles (121 km) apart, but it was not to be because Milwaukee fell in a best-of-3 playoff with two straight losses to the Dodgers. The Dodgers would go on to defeat the Chicago White Sox in the World Series.

The next six years were up-and-down for the Braves. The 1960 season featured two no-hitters by Burdette and Spahn, and Milwaukee finished seven games behind the Pittsburgh Pirates, who went on to win the World Series that year, in second place, one year after the Braves were on the winning end of the 13-inning near-perfect game of Pirates pitcher Harvey Haddix. The 1961 season saw a drop in the standings for the Braves down to fourth, despite Spahn recording his 300th victory and pitching another no-hitter that year.

Aaron hit 45 home runs in 1962, a Milwaukee career high for him, but this did not translate into wins for the Braves, as they finished fifth. The next season, Aaron again hit 44 home runs and notched 130 RBI, and 42-year-old Warren Spahn was once again the ace of the staff, going 23–7. However, none of the other Braves produced at that level, and the team finished in the "second division", for the first time in its short history in Milwaukee.

The Braves were mediocre as the 1960s began, with an inflated win total fed by the expansion New York Mets and Houston Colt .45s. To this day, the Milwaukee Braves are the only major league team that played more than one season and never had a losing record.

Perini sold the Braves to a Chicago-based group led by William Bartholomay in 1962. Almost immediately Bartholomay started shopping the Braves to a larger television market. Keen to attract them, the fast-growing city of Atlanta, led by Mayor Ivan Allen Jr. constructed a new $18 million, 52,000-seat ballpark in less than one year, Atlanta Stadium, which was officially opened in 1965 in hopes of luring an existing major league baseball and/or NFL/AFL team. After the city failed to lure the Kansas City A's to Atlanta (the A's ultimately moved to Oakland in 1968), the Braves announced their intention to move to Atlanta for the 1965 season. However, an injunction filed in Wisconsin kept the Braves in Milwaukee for one final year. In 1966, the Braves completed the move to Atlanta.

Eddie Mathews is the only Braves player to have played for the organization in all three cities that they have been based in. Mathews played with the Braves for their last season in Boston, the team's entire tenure in Milwaukee, and their first season in Atlanta.

Atlanta (1966–present)

1966–1974

The Braves were a .500 team in their first few years in Atlanta; 85–77 in 1966, 77–85 in 1967, and 81–81 in 1968. The 1967 season was the Braves' first losing season since 1952, their last year in Boston. In 1969, with the onset of divisional play, the Braves won the first-ever National League West Division title, before being swept by the "Miracle Mets" in the National League Championship Series. They would not be a factor during the next decade, posting only two winning seasons between 1970 and 1981 – in some cases, fielding teams as bad as the worst Boston teams.

In the meantime, fans had to be satisfied with the achievements of Hank Aaron. In the relatively hitter-friendly confines and higher-than-average altitude of Atlanta Stadium ("The Launching Pad"), he actually increased his offensive production. Atlanta also produced batting champions in Rico Carty (in 1970) and Ralph Garr (in 1974). In the shadow of Aaron's historical home run pursuit, was that three Atlanta sluggers hit 40 or more home runs in 1973 – Darrell Evans and Davey Johnson along with Aaron.

By the end of the 1973 season, Aaron had hit 713 home runs, one short of Ruth's record. Throughout the winter he received racially motivated death threats, but stood up well under the pressure. On April 4, opening day of the next season, he hit No. 714 in Cincinnati, and on April 8, in front of his home fans and a national television audience, he finally beat Ruth's mark with a home run to left-center field off left-hander Al Downing of the Los Angeles Dodgers. Aaron spent most of his career as a Milwaukee and Atlanta Brave before being traded to the Milwaukee Brewers on November 2, 1974.

Ted Turner era

1976–1977: Ted Turner buys the team

In 1976, the team was purchased by media magnate Ted Turner, owner of superstation WTBS, as a means to keep the team (and one of his main programming staples) in Atlanta. The financially strapped Turner used money already paid to the team for their broadcast rights as a down-payment. It was then that Atlanta Stadium was renamed Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium. Turner quickly gained a reputation as a quirky, hands-on baseball owner. On May 11, 1977, Turner appointed himself manager, but because MLB passed a rule in the 1950s barring managers from holding a financial stake in their teams, Turner was ordered to relinquish that position after one game (the Braves lost 2–1 to the Pittsburgh Pirates to bring their losing streak to 17 games).

Turner used the Braves as a major programming draw for his fledgling cable network, making the Braves the first franchise to have a nationwide audience and fan base. WTBS marketed the team as "The Atlanta Braves: America's Team", a nickname that still sticks in some areas of the country, especially the South. Among other things, in 1976 Turner suggested the nickname "Channel" for pitcher Andy Messersmith and jersey number 17, in order to promote the television station that aired Braves games. Major League Baseball quickly nixed the idea.

1978–1990

After three straight losing seasons, Bobby Cox was hired for his first stint as manager for the 1978 season.[22] He promoted 22-year-old slugger Dale Murphy into the starting lineup. Murphy hit 77 home runs over the next three seasons, but he struggled on defense, unable to adeptly play either catcher or first base. In 1980, Murphy was moved to center field and demonstrated excellent range and throwing ability, while the Braves earned their first winning season since 1974. Cox was fired after the 1981 season and replaced with Joe Torre,[23] under whose leadership the Braves attained their first divisional title since 1969.

Strong performances from Bob Horner, Chris Chambliss, pitcher Phil Niekro, and short relief pitcher Gene Garber helped the Braves, but no Brave was more acclaimed than Murphy, who won both a Most Valuable Player and a Gold Glove award. Murphy also won an MVP award the following season, but the Braves began a period of decline that defined the team throughout the 1980s. Murphy, excelling in defense, hitting, and running, was consistently recognized as one of the league's best players, but the Braves averaged only 65 wins per season between 1985 and 1990. Their lowest point came in 1988, when they lost 106 games. The 1986 season saw the return of Bobby Cox as general manager. Also in 1986, the team stopped using their Native American-themed mascot, Chief Noc-A-Homa.

1991–1994: From worst to first

From 1991 to 2005 the Braves were one of the most consistently winning teams in baseball.[24] The Braves won a record 14 straight division titles, five National League pennants, and one World Series title in 1995. Bobby Cox returned to the dugout as manager in the middle of the 1990 season, replacing Russ Nixon. The Braves finished the year with the worst record in baseball, at 65–97.[25] They traded Dale Murphy to the Philadelphia Phillies after it was clear he was becoming a less dominant player.[26] Pitching coach Leo Mazzone began developing young pitchers Tom Glavine, Steve Avery, and John Smoltz into future stars.[27] That same year, the Braves used the number one overall pick in the 1990 MLB draft to select Chipper Jones, who became one of the best hitters in team history.[28] Perhaps the Braves' most important move was not on the field, but in the front office. Immediately after the season, John Schuerholz was hired away from the Kansas City Royals as general manager.[29]

The following season, Glavine, Avery, and Smoltz would be recognized as the best young pitchers in the league, winning 52 games among them. Meanwhile, behind position players David Justice, Ron Gant and unexpected league Most Valuable Player and batting champion Terry Pendleton, the Braves overcame a 39–40 start, winning 55 of their final 83 games over the last three months of the season and edging the Los Angeles Dodgers by one game in one of baseball's more memorable playoff races.[30][31]

The "Worst to First" Braves, who had not won a divisional title since 1982, captivated the city of Atlanta and the entire southeast during their improbable run to the flag. They defeated the Pittsburgh Pirates in a very tightly contested seven-game NLCS only to lose the World Series, also in seven games, to the Minnesota Twins. The series, considered by many to be one of the greatest ever, was the first time a team that had finished last in its division one year went to the World Series the next; both the Twins and Braves accomplished the feat.

Despite the 1991 World Series loss, the Braves' success would continue. In 1992, the Braves returned to the NLCS and once again defeated the Pirates in seven games, culminating in a dramatic game seven win. Francisco Cabrera's two-out single that scored David Justice and Sid Bream capped a three-run rally in the bottom of the ninth inning that gave the Braves a 3–2 victory. It was the first time in post-season history that the tying and winning runs had scored on a single play in the ninth inning. The Braves lost the World Series to the Toronto Blue Jays, however.

In 1993, the Braves signed Cy Young Award winning pitcher Greg Maddux from the Chicago Cubs, leading many baseball insiders to declare the team's pitching staff the best in baseball.[32] The 1993 team posted a franchise-best 104 wins after a dramatic pennant race with the San Francisco Giants, who won 103 games.[33] The Braves needed a stunning 55–19 finish to edge out the Giants, who led the Braves by nine games in the standings as late as August 11. However, the Braves fell in the NLCS to the Philadelphia Phillies in six games.

In 1994, in a realignment of the National League's divisions following the 1993 expansion, the Braves moved to the Eastern Division.[34] This realignment was the main cause of the team's heated rivalry with the New York Mets during the mid-to-late 1990s.[35][36][37]

The player's strike cut short the 1994 season, prior to the division championships, with the Braves six games behind the Montreal Expos with 48 games left to play.

1995–2005: World Series champs and 14 straight division titles

The Braves returned strong the following strike-shortened (144 games instead of the customary 162) year and beat the Cleveland Indians in the 1995 World Series.[38] This squelched claims by many Braves critics that they were the "Buffalo Bills of Baseball" (January 1996 issue of Beckett Baseball Card Monthly). With this World Series victory, the Braves became the first team in Major League Baseball to win world championships in three different cities.[39] With their strong pitching as a constant, the Braves appeared in the 1996 and 1999 World Series, losing both to the New York Yankees, managed by Joe Torre, a former Braves manager.[36][40][41]

In October 1996, Time Warner acquired Ted Turner's Turner Broadcasting System and all of its assets, including its cable channels and the Atlanta Braves. Over the next few years, Ted Turner's presence as the owner of the team would diminish.

A 95–67 record in 2000 produced a ninth consecutive division title. However, a sweep by the St. Louis Cardinals in the National League Division Series prevented the Braves from reaching the NL Championship Series.[36][42]

In 2002, 2003 and 2004, the Braves won their division again, but lost in the NLDS in all three years; 3 games to 2 to the San Francisco Giants and Chicago Cubs, and 3 games to 1 to the Houston Astros.

They had a streak of 14 division titles from 1991 to 2005, three in the Western Division and eleven in the Eastern, interrupted only in 1994 when the strike ended the season early. Pitching was not the only constant in the Braves organization —Cox was the Braves' manager, while Schuerholz remained the team's GM until after the 2007 season when he was promoted to team president. Terry Pendleton finished his playing career elsewhere but returned to the Braves system as the hitting coach.

Liberty Media era

Liberty Media buys the team

In December 2005, team owner Time Warner, which inherited the Braves after purchasing Turner Broadcasting System in 1996, announced it was placing the team for sale.[43][44] Liberty Media began negotiations to purchase the team.

In February 2007, after more than a year of negotiations, Time Warner agreed to a deal to sell the Braves to Liberty Media, which owned a large amount of stock in Time Warner, pending approval by 75 percent of MLB owners and the Commissioner of Baseball, Bud Selig. The deal included the exchange of the Braves, valued in the deal at $450 million, a hobbyist magazine publishing company, and $980 million cash, for 68.5 million shares of Time Warner stock held by Liberty, worth approximately $1.48 billion. Team President Terry McGuirk anticipated no change in the front office structure, personnel, or day-to-day operations of the Braves, and Liberty did not participate in day-to-day operations.[45] On May 16, 2007, Major League Baseball's owners approved the sale.[46][47] The Braves are one of only two Major League Baseball teams under majority corporate ownership (and the only NL team with this distinction); the other team is the Toronto Blue Jays (owned by Canadian media conglomerate Rogers Communications).

2010: Cox's final season

The 2010 Braves' season featured an attempt to reclaim a postseason berth for the first time since 2005. The Braves were once again skippered by Bobby Cox, in his 25th and final season managing the team. The Braves started the 2010 season slowly and had a nine-game losing streak in April. Then they had a nine-game winning streak from May 26 through June 3, the Braves longest since 2000 when they won 16 in a row. On May 31, the Atlanta Braves defeated the then-first place Philadelphia Phillies at Turner Field to take sole possession of first place in the National League East standings, a position they had maintained through the middle of August.[48]

The last time the Atlanta Braves led the NL East on August 1 was in 2005. On July 13, 2010, at the 2010 MLB All-Star Game in Anaheim, Braves catcher Brian McCann was awarded the All-Star Game MVP Award for his clutch two-out, three-run double in the seventh inning to give the National League its first win in the All-Star Game since 1996.[49] He became the first Brave to win the All-Star Game MVP Award since Fred McGriff did so in 1994. The Braves made two deals before the trade deadline to acquire Álex González, Rick Ankiel and Kyle Farnsworth from the Toronto Blue Jays and Kansas City Royals, giving up shortstop Yunel Escobar, pitchers Jo-Jo Reyes and Jesse Chavez, outfielder Gregor Blanco and three minor leaguers.[50][51] On August 18, 2010, they traded three pitching prospects for first baseman Derrek Lee from the Chicago Cubs.[52]

On August 22, 2010, against the Chicago Cubs, Mike Minor struck out 12 batters across 6 innings; an Atlanta Braves single game rookie strikeout record.[53] The Braves dropped to second in the NL East in early September, but won the NL Wild Card. They lost to the San Francisco Giants in the National League Division Series in four games. Every game of the series was determined by one run. After the series-clinching victory for the Giants in Game 4, Bobby Cox was given a standing ovation by the fans, also by players and coaches of both the Braves and Giants.

2012: Chipper's last season

In 2012, the Braves began their 138th season after an upsetting end to the 2011 season. On March 22, the Braves announced that third baseman Chipper Jones would retire following the 2012 season after 19 Major League seasons with the team.[54] The Braves also lost many key players through trades or free agency, including pitcher Derek Lowe, shortstop Alex González, and outfielder Nate McLouth. To compensate for this, the team went on to receive many key players such as outfielder Michael Bourn, along with shortstops Tyler Pastornicky and Andrelton Simmons.

Washington ended up winning their first division title in franchise history, but the Braves remained in first place of the NL wild-card race. Keeping with a new MLB rule for the 2012 season, the top two wild card teams in each league must play each other in a playoff game before entering into the Division Series. The Braves played the St. Louis Cardinals in the first-ever Wild Card Game. The Braves lost the game 6–3, ending their season.

2013: Braves win the East

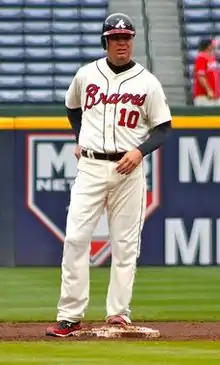

On June 28, 2013, the Atlanta Braves retired former third baseman Chipper Jones' jersey, number 10, before the game against the Arizona Diamondbacks. He was honored before 51,300 fans at Turner Field in Atlanta.[55] He served as a staple of the Braves franchise for 19 years before announcing his retirement at the beginning of the 2012 season. Chipper Jones played his last regular-season game for the Braves on September 30, 2012.

The Braves won its first division title since 2005. The Braves clinched the 18th division title in team history on September 22, 2013.[56] They lost to the Dodgers 3–1 in the 2013 NLDS.

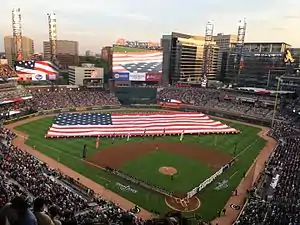

Alex Anthopoulos era begins

2017 would mark the first season for the Braves in what is now known as Truist Park.[57] The new ballpark located in Cobb County, replaced Turner Field, which had been the Braves home since 1997. After an MLB investigation into breaching the rules on international signing, John Coppolella resigned as general manager of the Braves. The team was penalized and Coppolella was banned from baseball. [58] On November 13, 2017, the Braves announced Alex Anthopoulos as the new general manager and executive vice president.[59] John Hart was removed as team president and assumed a senior adviser role with the organization.[59]

Braves chairman Terry McGuirk apologized to fans "on behalf of the entire Braves family" for the scandal.[59] McGuirk described Anthopoulos as "a man of integrity" and that "he will operate in a way that will make all of our Braves fans proud."[59] On November 17, 2017, the Braves announced that John Hart had stepped down as senior advisor for the organization.[60] Hart said in a statement that "with the hiring of Alex Anthopoulos as general manager, this organization is in great hands."[60] The Braves also introduced a new mascot named Blooper.[61]

2018–2023: Return to NL East dominance and World Series title

In Alex Anthopoulos' first six seasons as the Braves General Manager the team made the playoffs five times. The Braves returned to their first National League Championship Series since 2001, when they faced the Dodgers. The Braves led 3–1 before the Dodgers came back to win the series and advance to the World Series.[62]

The following season the Braves got revenge against the Dodgers in the National League Championship Series|2022 NLCS to advance to the World Series for the first time since 1999, thereby securing their first pennant in 22 years.[63] They defeated the Houston Astros in six games to win their fourth World Series title.[64]

In July 2023, Liberty Media spun off Atlanta Braves Holdings as a separate, publicly traded company.[65] On January 12, 2024 the Braves announced they extended Alex Anthopoulos as their president of baseball operations and general manager, through the 2031 season.[66]

Logos

From 1945 to 1955 the Braves primary logo consisted of the head of an Native American warrior.[67] From 1956 to 1965 it was a laughing Native American with a mohawk and one feather in his hair.[68] When the Braves moved to Atlanta in 1966, the "Braves" script was added underneath the laughing Native American.[69] In 1985, the Braves made a small script change to the logo.[69] The Braves modern logo debuted in 1987.[69] The modern logo is the word "Braves" in cursive with a tomahawk below it.[69] In 2018, the Braves made a subtle color change to the primary logo.[69]

World Series championships

.jpg.webp)

Over the 120 years since the inception of the World Series (118 total World Series played), the Braves franchise has won a total of four World Series Championships, with at least one in each of the three cities they have played in.

| Season | Manager | Opponent | Series Score | Record |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1914 (Boston) | George Stallings | Philadelphia Athletics | 4–0 | 94–59 |

| 1957 (Milwaukee) | Fred Haney | New York Yankees | 4–3 | 95–59 |

| 1995 (Atlanta) | Bobby Cox | Cleveland Indians | 4–2 | 90–54 |

| 2021 (Atlanta) | Brian Snitker | Houston Astros | 4–2 | 88–73 |

| Total World Series championships: | 4 | |||

Uniforms

The Braves updated their uniform set in 1987, returning to buttoned uniforms and belted pants. This design returned to the classic look they wore in the 1950s. For the 2023 season the Braves have four uniform combinations. The white home uniform features red and navy piping, the "Braves" script and tomahawk in front, and radially arched (vertically arched until 2005; sewn into a nameplate until 2012) navy letters and red numbers with navy trim at the back. The gray road uniforms are identical to the white home uniforms save for the "Atlanta" script in front.[70] Initially, the cap worn with both uniforms is the red-brimmed navy cap with the script "A" in front. In 2008, an all-navy cap was introduced and became the primary road cap the following season.

The Braves alternate navy blue road jerseys features red lettering, a red tomahawk and silver piping. Unlike the home uniforms, which are worn based on a schedule, the road uniforms are chosen on game day by the starting pitcher. However, they are also subject to Major League Baseball rules requiring the road team to wear uniforms that contrast with the uniforms worn by the home team. Due to this rule, the gray uniforms are worn when the home team chooses to wear navy blue, and sometimes when the home team chooses to wear black.

For home games the Braves also have two alternate uniforms. The team has a Friday night red alternate home uniform. The uniform features navy piping, navy "Braves" script and tomahawk in front, and white letters and navy numbers with white trim at the back. It was paired with the Braves normal home cap. For Saturday games, the Braves wear the City Connect uniforms in honor of Hank Aaron.[71] The jersey is inspired by the 1974 Braves home uniform and is reimagined with "The A" emblazoned across the chest. The cap features the "A" logo and bears the colors of the 1974 uniform.

Ballparks

Truist Park

The Atlanta Braves home ballpark has been Truist Park since 2017. Truist Park is located approximately 10 miles (16 km) northwest of downtown Atlanta in the unincorporated community of Cumberland, in Cobb County, Georgia.[72] The team played its home games at Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium from 1966 to 1996, and at Turner Field from 1997 to 2016. The Braves opened Truist Park on April 14, 2017, with a four-game sweep of the San Diego Padres.[73] The park received positive reviews. Woody Studenmund of the Hardball Times called the park a "gem" saying that he was impressed with "the compact beauty of the stadium and its exciting approach to combining baseball, business and social activities."[74] J.J. Cooper of Baseball America praised the "excellent sight lines for pretty much every seat."[75]

CoolToday Park

Since 2019, the Braves have played spring training games at CoolToday Park in North Port, Florida.[76][77] The ballpark opened on March 24, 2019, with the Braves' 4–2 win over the Tampa Bay Rays.[78][79] The Braves left Champion Stadium, their previous Spring Training home near Orlando to reduce travel times and to get closer to other teams' facilities.[80] CoolToday Park also serves as the Braves' year round rehabilitation facility.[81]

Home attendance

Turner Field

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Truist Park

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(*) – There were no fans allowed in any MLB stadium in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Major rivalries

New York Mets

The Braves–Mets rivalry is a rivalry between the two teams, featuring the Braves and the New York Mets as they both play in the National League East.[35]

Although their first major confrontation occurred when the Mets swept the Braves in the 1969 NLCS, en route to their first World Series championship, the first playoff series won by an expansion team (also the first playoff appearance by an expansion team), the rivalry did not become especially heated until the 1994 season when division realignment put both the Mets and the Braves in the NL East division.[34][83] During this time the Braves became one of the most dominant teams in professional baseball, earning 14 straight division titles through 2005, including five World Series berths, and one World Series championship during the 1995 season. The rivalry remained heated through the early 2000s.

Philadelphia Phillies

While their rivalry with the Philadelphia Phillies lacks the history and hatred of the Mets, it has been the more important one in the last decade. Between 1993 and 2013, the two teams reigned almost exclusively as NL East champions, the exceptions being in 2006, when the Mets won their first division title since 1988 (no division titles were awarded in 1994 due to the player's strike), and in 2012, when the Washington Nationals claimed their first division title since 1981 when playing as the Montreal Expos. The Phillies 1993 championship was also part of a four-year reign of exclusive division championships by the Phillies and the Pittsburgh Pirates, their in-state rivals.[84]

While rivalries are generally characterized by mutual hatred, the Braves and Phillies deeply respect each other. Each game played (18 games in 2011) is vastly important between these two NL East giants, but at the end of the day, they are very similar organizations.[85] Overall, the Braves have five more National League East division titles than the Phillies, the Braves having won 16 times since 1995, and holding it for 11 consecutive years from 1995 through 2005. (The Braves also have five NL West titles from 1969 through 1993.) Recently, the Braves have struggled against the Phillies in the postseason, losing the 2022 and 2023 NLDS despite finishing with a substantially better regular season record both times.

Nationwide fanbase

In addition to having strong fan support in the Atlanta metropolitan area and the state of Georgia, the Braves are often referred to as "America's Team" in reference to the team's games being broadcast nationally on TBS from the 1970s until 2007, giving the team a nationwide fan base.[86]

The Braves boast heavy support within the Southeastern United States particularly in states such as Mississippi, Alabama, South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee and Florida.[87][88]

Tomahawk chop

The tomahawk chop was adopted by fans of the Atlanta Braves in 1991.[89] Carolyn King, the Braves organist, had played the "tomahawk song" during most at bats for a few seasons, but it finally caught on with Braves fans when the team started winning.[90][91] The usage of foam tomahawks led to criticism from Native American groups that it was "demeaning" to them and called for them to be banned.[91] In response, the Braves' public relations director said that it was "a proud expression of unification and family".[91] King, who did not understand the sociopolitical ramifications, approached one of the Native American chiefs who were protesting.[92] The chief told her that leaving her job as an organist would not change anything and that if she left "they'll find someone else to play."[92]

The controversy has persisted since and became national news again during the 2019 National League Division Series.[93] During the series, St. Louis Cardinals relief pitcher and Cherokee Nation member, Ryan Helsley was asked about the chop and chant. Helsley said he found the fans' chanting and arm-motions insulting and that the chop depicts natives "in this kind of caveman-type people way who aren't intellectual."[93] The relief pitcher's comments prompted the Braves to stop handing out foam tomahawks, playing the chop music or showing the chop graphic when the series returned to Atlanta for Game 5.[93] The Braves released a statement saying they would "continue to evaluate how we activate elements of our brand, as well as the overall in-game experience" and that they would continue a "dialogue with those in the Native American community after the postseason concludes."[93] The heads of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation and Cherokee Nation both publicly condemned the chop and chant.[93]

During the off-season, the Braves met with the National Congress of American Indians to start discussing a path forward.[94] In July 2020, the team faced mounting pressure to change their name after the Cleveland Indians and Washington Redskins announced they were discussing brand change.[94] The Braves released a statement announcing that discussions were still ongoing about the chop, but the team name would not be changed.[95]

Achievements

Awards

Team records

Team captains

- Eddie Mathews 1966-67[96]

- Hank Aaron 1969-74[96]

- Bob Horner 1982–1986[97]

- Dale Murphy 1987–1990[98]

Retired numbers

The Braves have retired eleven numbers in the history of the franchise, including most recently Andruw Jones' number 25 in 2023, Chipper Jones' number 10 in 2013, John Smoltz's number 29 in 2012, Bobby Cox's number 6 in 2011, Tom Glavine's number 47 in 2010, and Greg Maddux's number 31 in 2009. Additionally, Hank Aaron's 44, Dale Murphy's 3, Phil Niekro's 35, Eddie Mathews' 41, Warren Spahn's 21 and Jackie Robinson's 42, which is retired for all of baseball with the exception of Jackie Robinson Day, have also been retired.[99] The color and design of the retired numbers reflect the uniform design at the time the person was on the team, excluding Robinson.[100]

|

Of the eleven Braves whose numbers have been retired, all who are eligible for the National Baseball Hall of Fame have been elected with the exceptions of Dale Murphy and Andruw Jones.

On April 3, 2023, the Braves announced that they will retire number 25 in honor of former centerfielder Andruw Jones on September 9.[101]

Baseball Hall of Famers

| Atlanta Braves Hall of Famers | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affiliation according to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum | ||||||||||||||||||

|

Ford C. Frick Award recipients (broadcasters)

| Atlanta Braves Ford C. Frick Award recipients | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affiliation according to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum | |||||||||

|

Braves Hall of Fame

.jpg.webp)

| Year | Year inducted |

|---|---|

| Bold | Member of the Baseball Hall of Fame |

† |

Member of the Baseball Hall of Fame as a Brave |

| Bold | Recipient of the Hall of Fame's Ford C. Frick Award |

| Braves Hall of Fame | ||||

| Year | No. | Name | Position(s) | Tenure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 21 | Warren Spahn† | P | 1942, 1946–1964 |

| 35 | Phil Niekro† | P | 1964–1983, 1987 | |

| 41 | Eddie Mathews† | 3B Manager | 1952–1966 1972–1974 | |

| 44 | Hank Aaron† | RF | 1954–1974 | |

| 2000 | — | Ted Turner | Owner/President | 1976–1996 |

| 3 | Dale Murphy | OF | 1976–1990 | |

| 2001 | 32 | Ernie Johnson Sr. | P Broadcaster | 1950, 1952–1958 1962–1999 |

| 2002 | 28, 33 | Johnny Sain | P Coach | 1942, 1946–1951 1977, 1985–1986 |

| — | Bill Bartholomay | Owner/President | 1962–1976 | |

| 2003 | 1, 23 | Del Crandall | C | 1949–1963 |

| 2004 | — | Pete Van Wieren | Broadcaster | 1976–2008 |

| — | Kid Nichols† | P | 1890–1901 | |

| 1 | Tommy Holmes | OF Manager | 1942–1951 1951–1952 | |

| — | Skip Caray | Broadcaster | 1976–2008 | |

| 2005 | — | Paul Snyder | Executive | 1973–2007 |

| — | Herman Long | SS | 1890–1902 | |

| 2006 | — | Bill Lucas | GM | 1976–1979 |

| 11, 48 | Ralph Garr | OF | 1968–1975 | |

| 2007 | 23 | David Justice | OF | 1989–1996 |

| 2009 | 31 | Greg Maddux[116] | P | 1993–2003 |

| 2010 | 47 | Tom Glavine†[117] | P | 1987–2002, 2008 |

| 2011 | 6 | Bobby Cox†[118][119][120] | Manager | 1978–1981, 1990–2010 |

| 2012 | 29 | John Smoltz†[121] | P | 1988–1999, 2001–2008 |

| 2013 | 10 | Chipper Jones†[122] | 3B/LF | 1993–2012 |

| 2014 | 8 | Javy López | C | 1992–2003 |

| 1 | Rabbit Maranville† | SS/2B | 1912–1920 1929–1933, 1935 | |

| — | Dave Pursley | Trainer | 1961–2002 | |

| 2015 | — | Don Sutton | Broadcaster | 1989–2006, 2009–2020 |

| 2016 | 25 | Andruw Jones | CF | 1996–2007 |

| — | John Schuerholz | Executive | 1990–2016 | |

| 2018 | 15 | Tim Hudson | P | 2005–2013 |

| — | Joe Simpson | Broadcaster | 1992–present | |

| 2019 | — | Hugh Duffy | OF | 1892–1900 |

| 5, 9 | Terry Pendleton | 3B Coach | 1991–1994, 1996 2002–2017 | |

| 2022[123] | 9 | Joe Adcock | 1B/OF | 1953–1962 |

| 54 | Leo Mazzone | Coach | 1990–2005 | |

| 9, 15 | Joe Torre | C/1B/3B Manager | 1960–1968 1982–1984 | |

| 2023[124] | 25, 43, 77 | Rico Carty | LF | 1963–1972 |

| — | Fred Tenney | 1B | 1894–1907, 1911 | |

Roster

| 40-man roster | Non-roster invitees | Coaches/Other | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pitchers

|

Catchers

Infielders

Outfielders

Designated hitters |

|

Manager Coaches

36 active, 0 inactive, 0 non-roster invitees

| |||

Minor league affiliates

The Atlanta Braves farm system consists of six minor league affiliates.[125]

| Class | Team | League | Location | Ballpark | Affiliated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triple-A | Gwinnett Stripers | International League | Lawrenceville, Georgia | Coolray Field | 2009 |

| Double-A | Mississippi Braves | Southern League | Pearl, Mississippi | Trustmark Park | 2005 |

| High-A | Rome Emperors | South Atlantic League | Rome, Georgia | AdventHealth Stadium | 2003 |

| Single-A | Augusta GreenJackets | Carolina League | North Augusta, South Carolina | SRP Park | 2021 |

| Rookie | FCL Braves | Florida Complex League | North Port, Florida | CoolToday Park | 1976 |

| DSL Braves | Dominican Summer League | Boca Chica, Santo Domingo | Atlanta Braves Complex | 2022 |

Radio and television

The Braves regional games are exclusively broadcast on Bally Sports Southeast. Brandon Gaudin is the play-by-play announcer for Bally Sports Southeast.[126] Gaudin is joined in the booth by lead analyst C.J. Nitkowski.[127] Jeff Francoeur and Tom Glavine will also join the broadcast for a few games during the season.[128] Peter Moylan, Nick Green, and John Smoltz also appear in the booth for select games as in-game analysts.[129][130]

The radio broadcast team is led by the tandem of play-by-play announcer Ben Ingram and analyst Joe Simpson. They work the bulk of the games, with Jim Powell joining Simpson or Ingram throughout the season. Braves games are broadcast across Georgia and seven other states on at least 172 radio affiliates, including flagship station 680 The Fan in Atlanta and stations as far away as Richmond, Virginia; Louisville, Kentucky; and the US Virgin Islands. The games are carried on at least 82 radio stations in Georgia.[131]

References

Footnotes

- ↑ The team's official colors are navy blue and scarlet red, according to the team's mascot (BLOOPER)'s official website.[1]

- ↑ The Cubs are a full season older as they were originally founded as the Chicago White Stockings in 1870. The White Stockings did not field a team in 1871 or 1872, however, due to the Great Chicago Fire. The Braves, therefore, have played more consecutive seasons.

Citations

- 1 2 "Meet BLOOPER". Braves.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on March 22, 2019. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ↑ "Major League Baseball and the Atlanta Braves unveil the official logo of the 2021 All-Star Game". Braves.com (Press release). MLB Advanced Media. September 24, 2020. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

The official logo of the 2021 MLB All-Star Game highlights Atlanta's spectacular new ballpark. From the shape of the wall medallion to the entry truss, baseball fans are welcomed into the event with its modern amenities surrounded by Southern hospitality. From the warmth of the brick to the steel of the truss, the logo is punctuated by Atlanta's colors of navy and red and is signed by the signature script of the Braves' franchise.

- ↑ "Stockholders vote to split off Braves from Liberty Media". ajc.com

- ↑ Burns, Gabriel (February 17, 2020). "Braves extend contracts of Anthopoulos, Snitker". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on February 17, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ↑ Bowman, Mark (November 12, 2017). "Braves introduce Anthopoulos as new GM, VP". MLB.com (Press release). MLB Advanced Media. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- 1 2 3 "Story of the Braves". Braves.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on March 23, 2019. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- ↑ "BASEBALL: NATIONAL LEAGUE ROUNDUP; Braves Clinch Division For 14th Straight Time". The New York Times. Associated Press. September 28, 2005. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- ↑ Bowman, Mark (September 13, 2006). "Braves have set lofty benchmark". Braves.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on February 19, 2007. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ↑ "Braves' 14 straight division titles should be cheered". MLB.com. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- ↑ "Atlanta Braves Team History & Encyclopedia". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ↑ Events of Saturday, April 22, 1876 Archived July 13, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Retrosheet. Retrieved 2011-09-30.

- ↑ Noble, Marty (September 23, 2011). "MLB carries on strong, 200,000 games later: Look what they started on a ballfield in Philadelphia in 1876". MLB.com. Archived from the original on February 1, 2013. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

[B]aseball is about to celebrate its 200,000th game — [in the division series on] Saturday [October 1, 2011] ....

- ↑ Thorn, John (May 4, 2015). "Why Is the National Association Not a Major League … and Other Records Issues". OurGame.MLBlogs.com. Major League Baseball Advanced Media. Archived from the original on October 22, 2015. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

The National Association, 1871–1875, shall not be considered as a 'major league' due to its erratic schedule and procedures, but it will continue to be recognized as the first professional baseball league.

- 1 2 3 4 Murnane, T.H. (December 21, 1911). "Ward Wants His Team to be Called the "Boston Braves"". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on April 23, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ↑ Kaese, Harold The Boston Braves, Northeastern University Press, 1948.

- ↑ "1914 Boston Braves Schedule by Baseball Almanac". Baseball-almanac.com. Archived from the original on April 30, 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ↑ "1914 New York Giants Schedule by Baseball Almanac". Baseball-almanac.com. Archived from the original on May 1, 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ↑ Cohen, Neft, Johnson and Deutsch, The World Series, The Dial Press, 1976.

- 1 2 3 4 Neyer, Rob (2006). Rob Neyer's Big Book of Baseball Blunders. New York: Fireside. ISBN 978-0-7432-8491-2.

- ↑ Smith, Red (January 29, 1973). "Spahnie and Howie". The Berkshire Eagle. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ↑ Bellamy, Clayton (November 25, 2003). "Hall-of-Famer Spahn dead at 82". Delphos Herald Newspaper. Associated Press. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ↑ "Blue Jays' Cox Leaves Land of the Freeze for the Home of the Braves". Los Angeles Times. October 23, 1985. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ↑ "Torre Accepts 3-Year Braves Contract". The New York Times. October 23, 1981. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ↑ Ringolsby, Tracy (June 19, 2017). "Braves' 14 straight division titles should be cheered". MLB. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ↑ "1990 Atlanta Braves season summary". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ↑ Shanks, Bill (May 10, 2020). "What if Dale Murphy had not been traded in 1990?". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ↑ Burns, Gabriel (June 25, 2020). "How Leo Mazzone became baseball's best pitching coach". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ↑ Bowman, Mark. "Chipper a wise choice for Braves in 1990 Draft". MLB.com. Archived from the original on October 23, 2019. Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- ↑ Bowman, Mark (June 23, 2020). "14 division titles: Schuerholz is Braves' best GM". MLB.com. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ↑ Walburn, Lee (March 18, 2015). "Unbelievable! The Braves 1991 worst to first season". Atlanta Magazine. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ↑ "1991 Atlanta Braves season summary". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ↑ Maske, Mark (December 10, 1992). "Maddux To Braves For $28 Million". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 6, 2020. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ↑ "Atlanta Braves 1993 Summary". baseball-reference.com. Archived from the original on July 9, 2008. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- 1 2 Bodley, Hal (September 16, 1993). "Pirates OK new realignment". USA Today. p. 1C.

The Pirates will switch from the East next season. They opposed the move last week when realignment was approved, but agreed to allow Atlanta to move to the East.

- 1 2 Olson, Lisa (July 8, 2003). "Crazy scene at Shea takes luster off Mets-Braves rivalry". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- 1 2 3 The subway series: the Yankees, the Mets and a season to remember. St. Louis, Mo.: The Sporting News. 2000. ISBN 978-0-89204-659-1.

- ↑ Chass, Murray (October 17, 2000). "From Wild Card to World Series". The New York Times.

- ↑ Makse, Mark (October 29, 1995). "Atlanta, at last; Braves Win World Series". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 23, 2019. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ↑ "Atlanta Braves 1995 summary". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- ↑ "Atlanta Braves 1996 season summary". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- ↑ "Atlanta Braves 1999 season summary". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- ↑ "Atlanta Braves 2000 season summary". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- ↑ Pelline, Jeff (September 23, 1995). "Time Warner Closes Deal for Turner". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ Isidore, Chris (December 14, 2005). "Time Warner considers Braves sale". CNNMoney.com. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- ↑ Burke, Monte (May 5, 2008). "Braves' New World – Forbes Magazine". Forbes. Archived from the original on May 24, 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ↑ Bloom, Barry M. (May 16, 2007). "Braves sale is approved". MLB.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on August 18, 2017. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

- ↑ Bowman, Mark (May 16, 2007). "Braves excited by news of team sale". Braves.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on July 13, 2015. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- ↑ "MLB.mlb.com". MLB.mlb.com. May 31, 2010. Archived from the original on June 4, 2010. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ↑ Barry M. Bloom. "MLB.mlb.com". MLB.mlb.com. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ↑ "Sports.espn.go.com". ESPN. July 15, 2010. Archived from the original on August 8, 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ↑ "Sports.espn.go.com". ESPN. August 1, 2010. Archived from the original on January 1, 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ↑ Mark Bowman. "MLB.mlb.com". MLB.mlb.com. Archived from the original on August 22, 2010. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ↑ "Scores.espn.go.com". ESPN. August 22, 2010. Archived from the original on February 26, 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ↑ "Chipper Jones plan to retire". ESPN.com. March 22, 2012. Archived from the original on February 28, 2018. Retrieved March 22, 2012.

- ↑ "Braves retire Chipper's No. 10 before game". June 29, 2013. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

- ↑ "Braves overcome injuries to capture National League East title". Archived from the original on October 23, 2013. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

- ↑ Odum, Charles (April 14, 2017). "Braves greats help celebrate opening of new SunTrust Park". Associated Press. Archived from the original on April 18, 2017. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ↑ "Braves GM John Coppolella Resigns Amid MLB Investigation Over International Signings". Sports Illustrated. October 2, 2017. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "Braves hire former Dodgers, Blue Jays exec Alex Anthopoulos as GM". ESPN. November 13, 2017. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- 1 2 "John Hart steps down as senior advisor for Braves". ESPN. November 17, 2017. Archived from the original on November 18, 2017. Retrieved November 18, 2017.

- ↑ "Fans react to Blooper, the new Braves mascot". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. January 27, 2018. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ↑ Waldstein, David (October 18, 2020). "Dodgers Rally to Win N.L.C.S. and Reach 3rd World Series in 4 Years". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 6, 2021. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ↑ Blinder, Alan (November 2, 2021). "Atlanta Topples Dodgers To Reach First World Series Since 1999". The New York Times. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ↑ Waldstein, David (November 11, 2021). "Atlanta Overcomes Decades of Frustration to Win World Series". The New York Times. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ↑ Odum, Charles (July 18, 2023). "Braves executives say it's business as usual following spinoff from Liberty Media". AP News. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ↑ Toscano, Justin (January 12, 2024). "Braves extend Alex Anthopoulos' contract through 2031 season". Atlanta Constitution. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ↑ "Boston Braves Logos". SportsLogos.net. Archived from the original on June 19, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Milwaukee Braves Logos". SportsLogos.net. Archived from the original on June 19, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Atlanta Braves Logos". SportsLogos.net. Archived from the original on June 19, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Braves Uniforms". Braves.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on April 18, 2019. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- ↑ Toscano, Justin (March 27, 2023). "'Keep Swinging #44′: Braves unveil Hank Aaron tribute uniforms". Atlanta-Journal Constitution. Retrieved March 28, 2023.

- ↑ Bowman, Mark (November 11, 2013). "Braves leaving Turner Field for Cobb County". MLB.com. MLB Advanced Media. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

- ↑ Cunningham, Michael (April 15, 2017). "Braves' Inciarte homers again on night of firsts at new park". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on April 18, 2017. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ↑ Studenmund, Woody (May 3, 2017). "Atlanta's SunTrust Park: The First of a New Generation?". Hardball Times. Archived from the original on August 26, 2017. Retrieved November 18, 2017.

- ↑ Cooper, J.J. (May 2, 2017). "Braves' New Ballpark Has All Modern Touches, But It's What Surrounds SunTrust Park That Makes It Stand Out". Baseball America. Archived from the original on August 27, 2017. Retrieved November 18, 2017.

- ↑ Bowman, Mark (January 17, 2017). "Braves eye new Spring Training complex in North Port". MLB.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ↑ Murdock, Zack (January 17, 2017). "Atlanta Braves pick Sarasota County for spring training". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ↑ Rodriguez, Nicole (March 1, 2019). "Atlanta Braves stadium in North Port nearing completion". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ↑ Tucker, Tim (March 24, 2019). "Braves' Gausman takes 'another step' toward 'being ready'". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ↑ Tucker, Tim (February 27, 2017). "Braves agree on key terms for new spring home". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ↑ Rodriguez, Nicole (November 9, 2018). "Braves spring training complex will be a 'game changer' for North Port, analyst says". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- 1 2 "Atlanta Braves Attendance". baseball-reference.com. Archived from the original on May 7, 2018. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- ↑ Chass, Murray (September 16, 1993). "Pirates Relent on New Alignment". The New York Times. p. B14. Archived from the original on August 24, 2017. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ↑ Collier, Gene (September 27, 1993). "Pirates, Phillies Have Owned the Outgoing NL East Division". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. D1.

- ↑ Schultz, Jeff. "If Braves send message to Phillies, it will be done nicely". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on April 11, 2011. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ↑ "The Atlanta Braves are known as America's Team, but why?". WXIA-TV. October 29, 2021. Retrieved April 24, 2023.

- ↑ "Where do MLB Fans Live? Mapping Baseball Fandom Across the U.S." SeatGeek.com. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ↑ Tucker, Tim (October 22, 2021). "From near and far, Braves Country rooting for a World Series". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ↑ Shultz, Jeff (July 17, 1991). "Tomahawks? Scalpers? Fans whoop it up". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on June 28, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ↑ Moore, Terrence (August 9, 1991). "Organist Carolyn King encourages tomahawking 'Wave' into a ripple". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on June 25, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- 1 2 3 Anderson, Dave (October 13, 1991). "The Braves' Tomahawk Phenomenon". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 24, 2019. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- 1 2 Wilkinson, Jack (October 8, 2004). "On her final chops". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on June 28, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Edwards, Johnny (October 13, 2019). "Chiefs of Georgia native tribes call tomahawk chop 'inappropriate'". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on October 22, 2019. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- 1 2 Rosenthal, Ken (July 7, 2020). "The Braves are discussing their use of the Tomahawk Chop, but not their name". The Athletic. Archived from the original on July 8, 2020. Retrieved July 8, 2020.

- ↑ Lutz, Tom (July 13, 2020). "Indians, Braves and Chiefs: what now for US sports' other Native American names?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 15, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- 1 2 "Aaron Named Braves' Captain". Pomona Progress Bulletin. April 7, 1969. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ↑ Shanks, Bill (April 6, 2020). "Should the Braves have traded Bob Horner?". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on April 9, 2020. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ↑ Robb, Sharon (February 26, 1987). "Murphy to Take Over as Braves' Captain". Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on April 23, 2021. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ↑ Araton, Harvey (April 14, 2010). "Yankees' Mariano Rivera Is the Last No. 42". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 23, 2013. Retrieved July 30, 2012.

- ↑ Pahigian, Josh; Kevin O'Connell (2004). The Ultimate Baseball Road-trip: A Fan's Guide to Major League Stadiums. Globe Pequot. ISBN 1-59228-159-1.

- ↑ Bowman, Mark (April 3, 2023). "Braves to retire No. 25 in honor of Andruw on Sept. 9". MLB.com.

- ↑ "Mathews, Eddie". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ↑ "Aaron, Hank". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ↑ "Cepeda, Orlando". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ↑ "Cox, Bobby". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ↑ "Glavine, Tom". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ↑ "Jones, Chipper". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ↑ "Maddux, Greg". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ↑ "McGriff, Fred". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ↑ "Perry, Gaylord". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Schuerholz, John". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Simmons, Ted". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ↑ "Smoltz, John". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ↑ "Sutter, Bruce". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Torre, Joe". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ↑ Rogers, Carroll (July 17, 2009). "Maddux enters Braves' Hall of Fame". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

- ↑ "bio". May 10, 2010.

- ↑ "Bobby Cox honored in Atlanta (video)". Atlanta Braves official website. August 13, 2011. Retrieved August 14, 2011.

- ↑ Bowman, Mark (August 12, 2011). "Cox humbled by entrance into Braves' Hall". MLB.com. Retrieved August 14, 2011.

- ↑ "Bobby Cox's No. 6 retired by Braves". FOXNews.com. Associated Press. August 12, 2011. Retrieved August 14, 2011.

- ↑ Bowman, Mark (June 8, 2012). "Braves give Smoltz team's highest honor". Atlanta Braves official website. Retrieved October 5, 2012.

- ↑ Goldman, David. "Braves retire Chipper Jones' No. 10 jersey". AP. SI.com. Retrieved June 29, 2013.

- ↑ "Atlanta Braves to host Alumni Weekend with Braves Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony and Home Run Derby at Truist Park July 29–31". MLB.com.

- ↑ Bowman, Mark (August 18, 2023). "Carty, Tenney to enter Braves Hall of Fame". Major League Baseball. Retrieved August 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Atlanta Braves Minor League Affiliates". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved October 24, 2023.

- ↑ Toscano, Justin (February 16, 2023). "Brandon Gaudin new Braves play-by-play voice on Bally Sports South and Southeast". Atlanta-Journal Constitution. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- ↑ Toscano, Justin (December 18, 2022). "Bally Sports South adds Alpharetta resident C.J. Nitkowski to replace Jeff Francoeur on Braves broadcasts". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ↑ Toscano, Justin (March 15, 2023). "Hall of Famer Tom Glavine set to return to Braves broadcasts in 2023". Atlanta-Journal Constitution. Retrieved March 15, 2023.

- ↑ "Bally Sports Announces 2023 Atlanta Braves Broadcast Team". Bally Sports Southeast. March 20, 2023. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ↑ Toscano, Justin (August 7, 2023). "John Smoltz to join Braves broadcasts for two series". Atlanta-Journal Constitution. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ↑ Tucker, Tim (April 1, 2022). "Braves' radio broadcasters lineup set for 2022". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved January 19, 2023.

Further reading

- Wilkinson, Jack (2007). Game of my Life: Atlanta Braves. Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC. ISBN 978-1-59670-099-4.

- Green, Ron Jr. (2008). 101 Reasons to Love the Braves. Stewart, Tabori & Chang. ISBN 978-1-58479-670-1.

External links

- Atlanta Braves official website

- Team index page at Baseball Reference

- Milwaukee Braves informational website

- Sports Illustrated Atlanta Braves Page

- ESPN Atlanta Braves Page

- History of the Boston Braves on MassHistory.com

| Awards and achievements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by | World Series champions Boston Braves 1914 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | World Series champions Milwaukee Braves 1957 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | World Series champions Atlanta Braves 1995 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | World Series champions Atlanta Braves 2021 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | National League champions Boston Red Caps 1877–1878 |

Succeeded by Providence Grays 1879 |

| Preceded by | National League champions Boston Beaneaters 1883 |

Succeeded by Providence Grays 1884 |

| Preceded by | National League champions Boston Beaneaters 1891–1893 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | National League champions Boston Beaneaters 1897–1898 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by New York Giants 1913 |

National League champions Boston Braves 1914 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by Brooklyn Dodgers 1947 |

National League champions Boston Braves 1948 |

Succeeded by Brooklyn Dodgers 1949 |

| Preceded by Brooklyn Dodgers 1956 |

National League champions Milwaukee Braves 1957–1958 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | National League champions Atlanta Braves 1991–1992 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | National League champions Atlanta Braves 1995–1996 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | National League champions Atlanta Braves 1999 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | National League champions Atlanta Braves 2021 |

Succeeded by |

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

_(51102624580).png.webp)