| 1689 Boston revolt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Glorious Revolution | |||||||

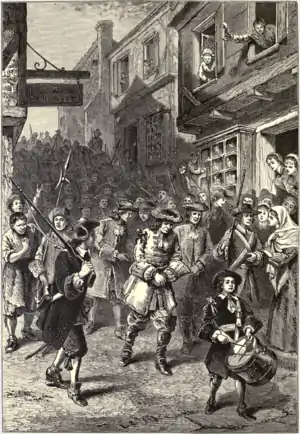

A 19th century interpretation showing the arrest of Governor Andros during Boston's brief revolt | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Simon Bradstreet Cotton Mather |

Sir Edmund Andros (POW) John George (POW) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

2,000 militia many citizens |

about 25 soldiers[1] (POW) one frigate | ||||||

The 1689 Boston revolt was a popular uprising on April 18, 1689 against the rule of Sir Edmund Andros, the governor of the Dominion of New England. A well-organized "mob" of provincial militia and citizens formed in the town of Boston, the capital of the dominion, and arrested dominion officials. Members of the Church of England were also taken into custody if they were believed to sympathize with the administration of the dominion. Neither faction sustained casualties during the revolt. Leaders of the former Massachusetts Bay Colony then reclaimed control of the government. In other colonies, members of governments displaced by the dominion were returned to power.

Andros was commissioned governor of New England in 1686. He had earned the enmity of the populace by enforcing the restrictive Navigation Acts, denying the validity of existing land titles, restricting town meetings, and appointing unpopular regular officers to lead colonial militia, among other actions. Furthermore, he had infuriated Puritans in Boston by promoting the Church of England, which was rejected by many nonconformist New England colonists.

Background

In the early 1680s, King Charles II of England sought to streamline the administration of the American colonies and bring them more closely under crown control.[2] He revoked the charter of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1684, after its leaders refused to act on his demands for reforms in the colony. Charles died in 1685, but Roman Catholic James II continued the efforts, culminating in his creation of the Dominion of New England.[3] He appointed former New York governor Sir Edmund Andros as dominion governor in 1686. The dominion was composed of the territories of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Plymouth Colony, Connecticut Colony, the Province of New Hampshire, and the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations.[4] In 1688, its jurisdiction was expanded to include New York, East Jersey, and West Jersey.[5]

Andros's rule was extremely unpopular in New England. He disregarded local representation, denied the validity of existing land titles in Massachusetts (which had been dependent on the old charter), restricted town meetings, and forced the Church of England into largely Puritan regions.[6] He also enforced the Navigation Acts which threatened the existence of certain trading practices of New England.[7] The royal troops stationed in Boston were often mistreated by their officers, who were supporters of the governor and often either Anglican or Roman Catholic.[8]

Meanwhile, King James became increasingly unpopular in England. He alienated otherwise supportive Tories with his attempts to relax the Penal Laws,[9] and he issued the Declaration of Indulgence in 1687 which established some freedom of religion, a move opposed by the Anglican church hierarchy. He increased the power of the regular army, an action seen by many Parliamentarians as a threat to their authority, and placed Catholics in important military positions.[10][11] James also attempted to place sympathizers in Parliament who he hoped would repeal the Test Act which required a strict Anglican religious test for many civil offices.[12] Some Whigs and Tories set aside their political differences when his son and potential successor James was born in June 1688,[13] and they conspired to replace him with his Protestant son-in-law William, Prince of Orange.[14] The Dutch prince had tried unsuccessfully to get James to reconsider his policies;[15] he agreed to an invasion, and the nearly bloodless revolution that followed in November and December 1688 established William and his wife Mary as co-rulers.[16]

The religious leaders of Massachusetts were led by Cotton and Increase Mather. They were opposed to the rule of Andros, and they organized dissent targeted to influence the court in London. Increase Mather sent an appreciation letter to the king regarding the Declaration of Indulgence, and he suggested to other Massachusetts pastors that they also express gratitude to him as a means to gain favor and influence.[17] Ten pastors agreed to do so, and they sent Increase Mather to England to press their case against Andros.[18] Dominion secretary Edward Randolph repeatedly attempted to stop him, including pressing criminal charges, but Mather clandestinely boarded a ship bound for England in April 1688.[19] He and other Massachusetts agents were received by King James in October 1688, who promised that the colony's concerns would be addressed. The events of the revolution, however, halted this attempt to gain redress.[20]

The Massachusetts agents then petitioned the new monarchs and the Lords of Trade (predecessors to the Board of Trade that oversaw colonial affairs) for restoration of the Massachusetts charter. Mather furthermore convinced the Lords of Trade to delay notifying Andros of the revolution.[21] He had already dispatched a letter to previous colonial governor Simon Bradstreet containing news of a report (prepared before the revolution) that the annulment of the Massachusetts charter had been illegal, and he urged the magistrates to "prepare the minds of the people for a change".[22] Rumors of the revolution apparently reached some individuals in Boston before official news arrived. Boston merchant John Nelson wrote of the events in a letter dated late March,[23] and the letter prompted a meeting of senior anti-Andros political and religious leaders in Massachusetts.[24]

Andros first received a warning of the impending revolt against his control while leading an expedition to fortify Pemaquid (Bristol, Maine), intending to protect the area against French and Indian attacks. In early January 1688/9,[lower-alpha 1] he received a letter from King James describing the Dutch military buildup.[25] On January 10, he issued a proclamation warning against Protestant agitation and prohibiting an uprising against the dominion.[26] The military force that he led in Maine was composed of British regulars and militia from Massachusetts and Maine. The militia companies were commanded by regulars who imposed harsh discipline that alienated the militiamen from their officers.[27] Andros was alerted to the meetings in Boston and also received unofficial reports of the revolution, and he returned to Boston in mid-March.[8][25] A rumor circulated that he had taken the militia to Maine as part of a so-called "popish plot;" the Maine militia mutinied, and those from Massachusetts began to make their way home.[28] A proclamation reached Boston in early April announcing the revolution; Andros had the messenger arrested, but his news was distributed, emboldening the people.[29] Andros wrote to his commander at Pemaquid on April 16 that "there is a general buzzing among the people, great with expectation of their old charter", even as he prepared to have the returning deserters arrested and shipped back to Maine.[30] The threat of arrests by their own colonial militia increased tensions between the people of Boston and the dominion government.[31]

Revolt in Boston

At about 5 a.m. on April 18, militia companies began gathering outside Boston at Charlestown just across the Charles River, and at Roxbury, located at the far end of the neck connecting Boston to the mainland.[lower-alpha 2] At about 8 a.m., the Charlestown companies boarded boats and crossed the river while the Roxbury companies marched down the neck and into the city. Simultaneously, men from the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company entered the homes of the regimental drummers in the city, confiscating their equipment. The militia companies met at about 8:30, joined by a growing crowd, and began arresting dominion and regimental leaders.[32] They eventually surrounded Fort Mary where Andros was quartered.[33]

Among the first to be arrested was Captain John George of HMS Rose who came ashore between 9 and 10 a.m., only to be met by a platoon of militia and the ship's carpenter who had joined the Americans.[32] George demanded to see an arrest warrant, and the militiamen drew their swords and took him into custody. By 10 a.m., most of the dominion and military officials had either been arrested or had fled to the safety of Castle Island or other fortified outposts. Boston Anglicans were rounded up by the people, including a church warden and an apothecary.[1] Sometime before noon, an orange flag was raised on Beacon Hill signaling another 1,500 militiamen to enter the city. These troops formed up in the market square, where a declaration was read which supported "the noble Undertaking of the Prince of Orange", calling the people to rise up because of a "horrid Popish Plot" that had been uncovered.[34]

The Massachusetts colonial leadership headed by ex-governor Simon Bradstreet then urged Governor Andros to surrender for his own safety.[35] He refused and tried to escape to Rose, but the militia intercepted a boat that came ashore from Rose, and Andros was forced back into Fort Mary.[36] Negotiations ensued and Andros agreed to leave the fort to meet with the council. He was promised safe conduct and marched under guard to the townhouse where the council had assembled. There he was told that "they must and would have the Government in their own hands", as an anonymous account describes it, and that he was under arrest.[37][38] Daniel Fisher grabbed him by the collar[39] and took him to the home of dominion official John Usher and held him under close watch.[38][40]

Rose and Fort William on Castle Island refused to surrender initially. On the 19th, however, the crew aboard Rose was told that the captain had planned to take the ship to France to join the exiled King James. A struggle ensued, and the Protestants among the crew took down the ship's rigging. The troops on Castle Island saw this and surrendered.[41]

Aftermath

Fort Mary surrendered on the 19th, and Andros was moved there from Usher's house. He was confined with Joseph Dudley and other dominion officials until June 7, when he was transferred to Castle Island. A story circulated widely that he had attempted an escape dressed in women's clothing.[42] This was disputed by Boston's Anglican minister Robert Ratcliff, who claimed that such stories had "not the least foundation of Truth" but were "falsehoods and lies" propagated to "render the Governour odious to his people".[43] Andros did make a successful escape from Castle Island on August 2 after his servant bribed the sentries with liquor. He managed to flee to Rhode Island but was recaptured soon after and kept in what was virtually solitary confinement.[44] He and others arrested in the wake of the revolt were held for 10 months before being sent to England for trial.[45] Massachusetts agents in London refused to sign the documents listing the charges against Andros, so he was summarily acquitted and released.[46] He later served as governor of Virginia and Maryland.[47]

Dissolution of the dominion

The other New England colonies in the dominion were informed of the overthrow of Andros, and colonial authorities moved to restore the governmental structures which had been in place prior to the dominion's enforcement.[48] Rhode Island and Connecticut resumed governance under their earlier charters, and Massachusetts resumed governance according to its vacated charter after being temporarily governed by a committee composed of magistrates, Massachusetts Bay officials, and a majority of Andros's council.[49] New Hampshire was temporarily left without formal government and was controlled by Massachusetts and its governor Simon Bradstreet, who served as de facto ruler of the northern colony.[50] Plymouth Colony also resumed its previous form of governance.[51]

During his captivity, Andros had been able to send a message to Francis Nicholson, his New York-based lieutenant governor. Nicholson received the request for assistance in mid-May, but most of his troops had been sent to Maine and he was unable to take any effective action because tensions were also rising in New York.[52] Nicholson himself was overthrown by a faction led by Jacob Leisler, and he fled to England.[53] Leisler governed New York until 1691 when a detachment of troops arrived[54] followed by Henry Sloughter, commissioned governor by William and Mary.[55] Sloughter had Leisler tried on charges of high treason; he was convicted and executed.[56]

No further effort was made by English officials to restore the shattered dominion after the suppression of Leisler's Rebellion and the reinstatement of colonial governments in New England.[57] Once Andros' arrest was known, the discussion in London turned to dealing with Massachusetts and its revoked charter. This led to formation of the Province of Massachusetts Bay in 1691, merging Massachusetts with Plymouth Colony and territories previously belonging to New York, including Nantucket, Martha's Vineyard, the Elizabeth Islands, and parts of Maine. Increase Mather was unsuccessful in his attempts to restore the old Puritan rule; the new charter called for an appointed governor and religious toleration.[58][59]

See also

- Leisler's Rebellion, a similar 1689 rebellion against the pro-Anglican governor of the Province of New York in the wake of the revolt

- Gove's Rebellion

Notes

- ↑ In the Julian calendar in use in England and its colonies at this time, the new year began on March 25. To avoid date confusion with the Gregorian calendar in use elsewhere, dates between January 1 and March 25 were sometimes written with both years.

- ↑ Charlestown and Roxbury were separate communities at this time, not part of Boston.

References

- 1 2 Lustig, p. 192

- ↑ Lovejoy, pp. 155–57, 169–70

- ↑ Lovejoy, p. 170

- ↑ Barnes, pp. 46–48

- ↑ Barnes, p. 223

- ↑ Lovejoy, pp. 180, 192–93, 197

- ↑ Barnes, pp. 169–70

- 1 2 Webb, p. 184

- ↑ Miller, pp. 162–64

- ↑ Lovejoy, p. 221

- ↑ Webb, pp. 101–07

- ↑ Miller, p. 178

- ↑ Miller, p. 186

- ↑ Lustig, p. 185

- ↑ Miller, p. 176

- ↑ Lovejoy, pp. 226–28

- ↑ Hall, pp. 207–10

- ↑ Hall, p. 210

- ↑ Hall, pp. 210–11

- ↑ Hall, p. 217

- ↑ Barnes, pp. 234–35

- ↑ Barnes, p. 238

- ↑ Steele, p. 77

- ↑ Steele, p. 78

- 1 2 Lustig, p. 182

- ↑ Webb, p. 182

- ↑ Webb, p. 183

- ↑ Webb, p. 185

- ↑ Lustig, p. 190

- ↑ Webb, pp. 186–87

- ↑ Webb, p. 187

- 1 2 Webb, p. 188

- ↑ Lustig, pp. 160, 192

- ↑ Webb, pp. 190–91

- ↑ Lustig, p. 193

- ↑ Webb, p. 191

- ↑ Palfrey, p. 586

- 1 2 Webb, p. 192

- ↑ Hanson, Robert Brand (1976). Dedham, Massachusetts, 1635–1890. Dedham Historical Society.

- ↑ Lustig, pp. 145, 197

- ↑ Webb, p. 193

- ↑ Fiske, p. 272

- ↑ Lustig, pp. 200–01

- ↑ Lustig, p. 201

- ↑ Lustig, p. 202

- ↑ Kimball, pp. 53–55

- ↑ Lustig, pp. 244–45

- ↑ Palfrey, p. 596

- ↑ Lovejoy, pp. 247, 249

- ↑ Tuttle, pp. 1–12

- ↑ Lovejoy, p. 246

- ↑ Lustig, p. 199

- ↑ Lovejoy, pp. 255–56

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, "Leisler, Jacob"

- ↑ Lovejoy, pp. 326–38

- ↑ Lovejoy, pp. 355–57

- ↑ Evans, p. 430

- ↑ Evans, pp. 431–49

- ↑ Barnes, pp. 267–69

Bibliography

- Barnes, Viola Florence (1960) [1923]. The Dominion of New England: A Study in British Colonial Policy. New York: Frederick Ungar. ISBN 978-0-8044-1065-6. OCLC 395292.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Evans, James Truslow (1922). The Founding of New England. Boston: The Atlantic Monthly Press. OCLC 1068441.

- Fiske, John (1889). The Beginnings of New England. Cambridge, MA: The Riverside Press. OCLC 24406793.

- Hall, Michael Garibaldi (1988). The Last American Puritan: The Life of Increase Mather, 1639–1723. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0-8195-5128-3. OCLC 16578800.

- Kimball, Everett (1911). The Public Life of Joseph Dudley. New York: Longmans, Green. OCLC 1876620.

- Lovejoy, David (1987). The Glorious Revolution in America. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0-8195-6177-0. OCLC 14212813.

- Lustig, Mary Lou (2002). The Imperial Executive in America: Sir Edmund Andros, 1637–1714. Madison, WI: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-3936-8. OCLC 470360764.

- Miller, John (2000). James II. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08728-4. OCLC 44694564.

- Palfrey, John (1864). History of New England: History of New England During the Stuart Dynasty. Boston: Little, Brown. OCLC 1658888.

- Steele, Ian K (March 1989). "Origins of Boston's Revolutionary Declaration of 18 April 1689". New England Quarterly. 62 (1): 75–81. doi:10.2307/366211. JSTOR 366211.

- Tuttle, Charles Wesley (1880). New Hampshire Without Provincial Government, 1689–1690: an Historical Sketch. Cambridge, MA: J. Wilson and Son. OCLC 12783351.

- Webb, Stephen Saunders (1998). Lord Churchill's Coup: The Anglo-American Empire and the Glorious Revolution Reconsidered. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-0558-4. OCLC 39756272.