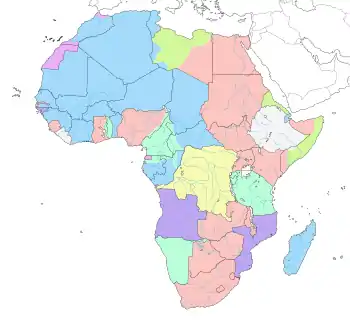

The 1890 British Ultimatum was an ultimatum by the British government delivered on 11 January 1890 to the Kingdom of Portugal. Portugal had attempted to claim a large area of land between its colonies of Mozambique and Angola including most of present-day Zimbabwe and Zambia and a large part of Malawi, which had been included in Portugal's "Rose-coloured Map".[1] The ultimatum led to the withdrawal of Portuguese forces from areas which had been claimed by Portugal on the basis of Portuguese exploration in the era, but which Britain claimed on the basis of uti possidetis.

It has sometimes been claimed that the British government's objections arose because the Portuguese claims clashed with its aspirations to create a Cape to Cairo Railway, linking its colonies from the south of Africa to those in the north. This seems unlikely, as in 1890 Germany already controlled German East Africa, now Tanzania, and Sudan was independent under Muhammad Ahmad. Rather, the British government was pressed into taking action by Cecil Rhodes, whose British South Africa Company was founded in 1888 south of the Zambezi and the African Lakes Company and British missionaries to the north.[2]

Background

At the start of the 19th century, the Portuguese presence in Africa south of the equator was limited in Angola to Luanda and Benguela and a few outposts, the most northerly of which was Ambriz and in Mozambique to the Island of Mozambique, several other coastal trading posts as far south as Delagoa Bay and the virtually independent Prazo estates in the Zambezi valley [3] The first challenge to Portugal's wider claims came from the Transvaal Republic, which in 1868 claimed an outlet to the Indian Ocean at Delagoa Bay. Although in 1869, Portugal and the Transvaal reached agreement on a border under which all of Delagoa Bay was Portuguese, the UK then lodged an objection, claiming the southern part of that bay. The claim was rejected after arbitration by President MacMahon of France. His award made in 1875 upheld the border agreed in 1869. A second challenge came from the foundation of a German colony at Angra Pequena, now known as Lüderitz in Namibia in 1883. Although there was no Portuguese presence there, Portugal had claimed it on the basis of discovery.[4]

A far more serious dispute arose in the area of the Zambezi valley and Lake Nyasa. Portugal occupied the coast of Mozambique from the 16th century, and from 1853 the Portuguese government embarked on a series of military campaigns to bring the Zambezi valley under its effective control.[5] During the 1850s, the areas south of Lake Nyasa (now Lake Malawi) and west of the lake were explored by David Livingstone and several Church of England and Presbyterian missions were established in the Shire Highlands in the 1860s and 1870s. In 1878, the African Lakes Company was established by businessmen with links to the Presbyterian missions. Their aim was to set up a trading company that would work in close cooperation with the missions to combat the slave trade by introducing legitimate trade and develop European influence in the area. A small mission and trading settlement was established at Blantyre in 1876.[6]

Portugal attempted to assert its African territorial claims through three expeditions led by Alexandre de Serpa Pinto, first from Mozambique to the eastern Zambezi in 1869, then to the Congo and upper Zambezi from Angola in 1876 and lastly crossing Africa from Angola in 1877–1879. These expeditions were undertaken with the intention of claiming the area between Mozambique and Angola.[7] Following Serpa Pinto's explorations, the Portuguese government in 1879 made a formal claim to the area south and east of the Ruo River (the present south-eastern border of Malawi) and, in 1882, occupied the lower Shire River valley as far as the Ruo. The Portuguese then asked the British government to accept this territorial claim, but the opening of the Berlin Conference of 1884–85 ended the discussions.[8] Portugal's efforts to establish this corridor of influence between Angola and Mozambique were hampered by one of the articles in the General Act of the Berlin Conference which required uti possidetis of areas claimed rather than historical claims based on discovery or those based on exploration, as Portugal had used.[9]

To validate Portuguese claims, Serpa Pinto was appointed as its consul in Zanzibar in 1884 and given the mission of exploring the region between Lake Nyasa and the coast from the Zambezi to the Rovuma River and securing the allegiance of the chiefs in that area.[10] His expedition reached Lake Nyasa and the Shire Highlands but failed to make any treaties of protection with the chiefs in territories west of the lake.[11] At the northwest end of Lake Nyasa around Karonga, the African Lakes Company made, or claimed to have made, treaties with local chiefs between 1884 and 1886. Its ambition was to become a chartered company and control the route from the lake along the Shire River.[12]

Despite the outcome of the Berlin Conference, the idea of a trans-African Portuguese zone was not abandoned; to help to create it, Portugal signed treaties with France and Germany in 1886. The German treaty noted Portugal's claim to territory along the course of the Zambezi linking Angola and Mozambique. Following the treaties, the Portuguese foreign minister prepared what became known as the Rose Coloured Map, representing a claim stretching from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean.[9] North of the Zambezi, these Portuguese claims were opposed by both the African Lakes company and the missionaries. The main opposition to Portuguese claims in the south came from Cecil Rhodes, whose British South Africa Company was founded in 1888.[13] As late as 1888, the British Foreign Office declined to offer protection to the tiny British settlements in the Shire Highlands. However, it did not accept the expansion of Portuguese influence there, and in 1889, it appointed Henry Hamilton Johnston as British consul to Mozambique and the Interior, and instructed him to report on the extent of Portuguese rule in the Zambezi and Shire valleys. He was also to make conditional treaties with local rulers outside Portuguese control. The conditional treaties did not establish a British protectorate but prevented the rulers from accepting protection from another state.[14]

Ultimatum

In 1888, the Portuguese government instructed its representatives in Mozambique to make treaties of protection with the Yao chiefs southeast of Lake Nyasa and in the Shire Highlands. Two expeditions were organised, one under Antonio Cardoso, a former governor of Quelimane, set off in November 1888 for Lake Nyasa; the second expedition under Serpa Pinto (now governor of Mozambique) moved up the Shire valley. Between them, these two expeditions made over 20 treaties with chiefs in what is now Malawi.[15] Serpa Pinto met Johnston in August 1889 east of the Ruo, when Johnston advised him not to cross the river into the Shire Highlands.[16] Although Serpa Pinto had previously acted with caution, he crossed the Ruo to Chiromo, now in Malawi in September 1889.[17]

The incursion led to an armed conflict between Portuguese troops led by Serpa Pinto and the Makololo on 8 November 1889 near the Shire river.[18]

Following this minor clash, Johnston's vice-consul, John Buchanan, accused Portugal of ignoring British interests in this area and declared a British protectorate over the Shire Highlands in December 1889 despite contrary instructions.[19] Shortly afterward, Johnston himself declared a further protectorate over the area to the west of Lake Nyasa (also contrary to his instructions) although both protectorates were later endorsed by the Foreign Office.[20]

The actions formed the background to an Anglo-Portuguese crisis in which a British refusal of arbitration was followed by the 1890 British Ultimatum.[21]

The ultimatum was a memorandum sent to the Portuguese Government by Lord Salisbury on 11 January 1890 in which he demanded the withdrawal of the Portuguese troops from Mashonaland and Matabeleland (now Zimbabwe) and the Shire-Nyasa region (now Malawi), where Portuguese and British interests in Africa overlapped. It meant that the UK was now claiming sovereignty over territories, some of which had been claimed as Portuguese for centuries.[22]

What Her Majesty's Government require and insist upon is the following: that telegraphic instructions shall be sent to the governor of Mozambique at once to the effect that all and any Portuguese military forces which are actually on the Shire or in the Makololo or in the Mashona territory are to be withdrawn. Her Majesty's Government considers that without this the assurances given by the Portuguese Government are illusory. Mr. Petre is compelled by his instruction to leave Lisbon at once with all the members of his legation unless a satisfactory answer to this foregoing intimation is received by him in, the course of this evening, and Her Majesty's ship Enchantress is now at Vigo waiting for his orders.[23]

The Mr. Petre mentioned was the British Minister in Lisbon.[23]

Aftermath

Although the ultimatum required Portugal to cease from its activities in the disputed areas, there was no similar restriction on further British efforts to establish occupation there. Agents for Rhodes were active in Mashonaland and Manicaland and in what is now eastern Zambia, and John Buchanan asserted British rule in more of the Shire Highlands. There were armed clashes between Portuguese troops who were already in occupation in Manicaland and Rhodes’ incoming men in 1890 and 1891, which ceased only when some areas that had been allocated to Portugal in the unratified 1890 treaty were reassigned to Rhodes’ British South Africa Company in the 1891 treaty, with Portugal being given more land in the Zambezi valley in compensation for this loss.[24]

The seeming ease by which the Portuguese government had acquiesced to the British demands was seen as a national humiliation by many in Portugal, including republican opponents of Portugal's monarchy. Portuguese anger over the ultimatum led to the fall of Prime Minister José Luciano de Castro's administration and its replacement by a new administration led by António de Serpa Pimentel. Combined with a variety of other factors, such as the Portuguese royal family's expenses, the Lisbon Regicide, political instability and changing religious and social views in Portugal led to the 5 October 1910 revolution, which overthrew the Portuguese monarchy.[25] The reason that Lord Salisbury and his diplomatically isolated British government used tactics that could have led to war has been plausibly argued as the result of fear of Portuguese occupation of Manicaland and the Shire Highlands, which would have forestalled British interests.[26]

In an attempt to reach an agreement over Portuguese African borders, the Treaty of London defining the territorial limits of Angola and Mozambique, was signed on 20 August 1890 by Portugal and the United Kingdom. The treaty was published in the Diário do Governo (Portugal's Government Daily) on 30 August and presented to the parliament that same day, leading to a new wave of protests and the downfall of the Portuguese government. Not only was it never ratified by the Portuguese Parliament; but Cecil Rhodes, whose plans of expansion it affected, also opposed this treaty. A new treaty was negotiated which gave Portugal more territory in the Zambezi valley than the 1890 treaty, but what is now the Manicaland Province of Zimbabwe passed from Portuguese to British control. This treaty was signed in Lisbon on 11 June 1891, and in addition to defining boundaries, it allowed freedom of navigation on the Zambezi and Shire rivers and allowed the UK to lease land for a port at Chinde at the mouth of the Zambezi.[27]

The 1890 ultimatum soured Anglo-Portuguese relations for some time, although when in the late 1890s Portugal underwent a severe economic crisis, its government sought a British loan. However, with the outbreak of the Boer war, Britain sought support from Portugal and signed an Anglo-Portuguese Declaration on 14 October 1899. This new treaty reaffirmed former treaties of Alliance and committed Britain to defending Portuguese colonies from possible enemies. In return, Portugal agreed to stop arms being supplied to the Transvaal through Lourenço Marques and declared its neutrality in the conflict.[28]

Although official relations were repaired, the 1890 ultimatum was said to be one of the main causes of the failed 31 January 1891 revolt by republicans in Porto and, eventually, the successful 5 October 1910 revolution, which ended the monarchy in Portugal 20 years later, around three years after the assassination of the Portuguese king (Carlos I of Portugal) and the crown prince on 1 February 1908.

See also

References

- ↑ Livermore, H.V. (1997). "Lord Salisbury's Ultimatum". British Historical Society of Portugal Annual Report. 24: 151.

- ↑ M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, London, Hurst & Co, p. 341. ISBN 1-85065-172-8.

- ↑ R Oliver and A Atmore (1986). The African Middle Ages, 1400–1800, Cambridge University Press pp. 163–164, 191, 195. ISBN 0-521-29894-6.

- ↑ H. Livermore (1992), Consul Crawfurd and the Anglo-Portuguese Crisis of 1890 Portuguese Studies, Vol. 8, pp. 181–2.

- ↑ M Newitt (1969). "The Portuguese on the Zambezi: An Historical Interpretation of the Prazo system", Journal of African History Vol. X, No. 1 pp. 67–68, 80–82. JSTOR 180296.

- ↑ J G Pike (1969). Malawi: A Political and Economic History, London, Pall Mall Press pp. 77–79.

- ↑ C E Nowell (March 1947). "Portugal and the Partition of Africa", The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 6–8. JSTOR 1875649.

- ↑ J McCracken (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, Woodbridge, James Currey, p. 51. ISBN 978-1-84701-050-6.

- 1 2 Teresa Pinto Coelho (2006). "Lord Salisbury's 1890 Ultimatum to Portugal and Anglo-Portuguese Relations", p. 2.

- ↑ C E Nowell (March 1947). "Portugal and the Partition of Africa", The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 19, No. 1, p. 10. JSTOR 1875649.

- ↑ M Newitt (1995). A History of Mozambique, pp. 276–277, 325–326.

- ↑ J McCracken (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, Woodbridge, James Currey, pp. 48–52. ISBN 978-1-84701-050-6.

- ↑ M Newitt (1995). A History of Mozambique, p. 341.

- ↑ J G Pike (1969). Malawi: A Political and Economic History, pp. 83–85.

- ↑ J McCracken, (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859-1966, pp. 52-3.

- ↑ J G Pike, (1969). Malawi: A Political and Economic History, pp. 85-6.

- ↑ J McCracken, (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859-1966, pp. 53, 55.

- ↑ Teresa Pinto Coelho, (2006). Lord Salisbury's 1890 Ultimatum to Portugal and Anglo-Portuguese Relations, p. 3. http://www.mod-langs.ox.ac.uk/files/windsor/6_pintocoelho.pdf

- ↑ M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, p. 346.

- ↑ R I Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa: The Making of Malawi and Zambia, 1873-1964, Cambridge (Mass), Harvard University Press, p.15.

- ↑ F Axelson, (1967). Portugal and the Scramble for Africa, Johannesburg, Witwatersrand University Press, pp. 233-6.

- ↑ Teresa Pinto Coelho, (2006). Lord Salisbury's 1890 Ultimatum to Portugal and Anglo-Portuguese Relations, p. 1. http://www.mod-langs.ox.ac.uk/files/windsor/6_pintocoelho.pdf

- 1 2 Teresa Pinto Coelho, (2006). Lord Salisbury's 1890 Ultimatum to Portugal and Anglo-Portuguese Relations, p. 1. http://www.mod-langs.ox.ac.uk/files/windsor/6_pintocoelho.pdf

- ↑ M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, pp. 353-4.

- ↑ João Ferreira Duarte, The Politics of Non-Translation: A Case Study in Anglo-Portuguese Relations

- ↑ M Newitt, (1995). A History of Mozambique, p. 347.

- ↑ Teresa Pinto Coelho, (2006). Lord Salisbury's 1890 Ultimatum to Portugal and Anglo-Portuguese Relations, pp. 6-7. http://www.mod-langs.ox.ac.uk/files/windsor/6_pintocoelho.pdf

- ↑ Teresa Pinto Coelho, (2006). Lord Salisbury's 1890 Ultimatum to Portugal and Anglo-Portuguese Relations, pp. 6-7. http://www.mod-langs.ox.ac.uk/files/windsor/6_pintocoelho.pdf

Further reading

- Charles E. Nowell, The Rose-Colored Map: Portugal's Attempt to Build an African Empire from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean. Lisbon, Portugal: Junta de Investigações Científicas do Ultramar, 1982.