| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United Kingdom |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism |

|---|

|

Conservatism in the United Kingdom is related to its counterparts in other Western nations, but has a distinct tradition and has encompassed a wide range of theories over the decades of conservatism. The Conservative Party, which forms the mainstream right-wing party in Britain, has developed many different internal factions and ideologies.

History

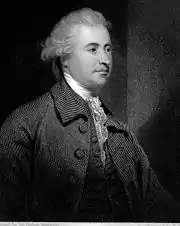

Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke is often considered the father of modern English conservatism in the English-speaking world.[1][2][3] Burke was a member of a conservative faction of the Whig party;[note 1] the modern Conservative Party however has been described by Lord Norton of Louth as "the heir, and in some measure the continuation, of the old Tory Party",[4] and the Conservatives are often still referred to as Tories.[5] The Australian scholar Glen Worthington has said: "For Edmund Burke and Australians of a like mind, the essence of conservatism lies not in a body of theory, but in the disposition to maintain those institutions seen as central to the beliefs and practices of society."[6]

Tories

The old established form of English and, after the Act of Union, British conservatism, was the Tory Party. It reflected the attitudes of a rural landowning class, and championed the institutions of the monarchy, the Anglican Church, the family, and property as the best defence of the social order. In the early stages of the Industrial Revolution, it seemed to be totally opposed to a process that seemed to undermine some of these bulwarks, and the new industrial elite were seen by many as enemies to the social order. It split in 1846 following the repeal of the Corn Laws (the tariff on imported corn). Proponents of free trade in the late 19th and early 20th centuries failed to make much headway as "tariff reform" resulted in new tariffs. The coalition of traditional landowners and sympathetic industrialists constituted the new Conservative Party.[7]

One-nation conservatism

Conservatism evolved after 1820, embracing imperialism and realization that an expanded working-class electorate could neutralize the Liberal advantage among the middle classes. Disraeli defined the Conservative approach and strengthened Conservatism as a grassroots political force. Conservatism no longer was the philosophical defence of the landed aristocracy but had been refreshed into redefining its commitment to the ideals of order, both secular and religious, expanding imperialism, strengthened monarchy, and a more generous vision of the welfare state as opposed to the punitive vision of the Whigs and Liberals.[8] As early as 1835, Disraeli attacked the Whigs and utilitarians as slavishly devoted to an industrial oligarchy, while he described his fellow Tories as the only "really democratic party of England" and devoted to the interests of the whole people.[9] Nevertheless, inside the party there was a tension between the growing numbers of wealthy businessmen on the one side, and the aristocracy and rural gentry on the other.[10] The aristocracy gained strength as businessmen discovered that they could use their wealth to buy a peerage and a country estate.

Disraeli set up a Conservative Central Office, established in 1870, and the newly formed National Union (which drew together local voluntary associations), gave the party "additional unity and strength", and Disraeli's views on social reform and the wealth disparity between the richest and poorest in society allegedly "helped the party to break down class barriers", according to the Conservative peer Lord Norton.[4] As a young man, Disraeli was influenced by the romantic movement and medievalism, and developed a critique of industrialism. In his novels, he outlined an England divided into two nations, each living in perfect ignorance of each other. He foresaw, like Karl Marx, the phenomenon of an alienated industrial proletariat. His solution involved a return to an idealized view of a corporate or organic society, in which everyone had duties and responsibilities towards other people or groups.[11]

This "one nation" conservatism is still a significant tradition in British politics, in both the Conservative Party[12][13][14] and Labour,[note 2][15] especially with the rise of the Scottish National Party during the 2015 general election.[16]

Although nominally a Conservative, Disraeli was sympathetic to some of the demands of the Chartists and argued for an alliance between the landed aristocracy and the working class against the increasing power of the middle class, helping to found the Young England group in 1842 to promote the view that the rich should use their power to protect the poor from exploitation by the middle class. The conversion of the Conservative Party into a modern mass organisation was accelerated by the concept of Tory Democracy attributed to Lord Randolph Churchill, father of Winston Churchill.[17]

Early 20th century

Winston Churchill, although best known as the most prominent conservative since Disraeli, crossed the aisle in 1904 and became a Liberal for two decades. As one of the most active and aggressive orators of his day, he thrilled the left in 1909 by ridiculing the Conservatives as, "the party of the rich against the poor, of the classes ... against the masses, of the lucky, the wealthy, the happy, and the strong against the left-out and the shut-out millions of the weak and poor." His harsh words were hurled back at him when he rejoined the Conservative Party in 1924.[18]

The shock of a landslide defeat in 1906 forced the Conservatives to rethink their operations, and they worked to build grassroots organisations that would help them win votes.[19] Responding to their defeat, the Conservative Party created the Workers Defence Union (WDU), which was designed to frighten the working class into voting for them. Though the WDU initially promoted tariff reform to protect domestic factory jobs, it soon switched to launching xenophobic and antisemitic attacks on immigrant workers and business owners, achieving considerable success by arousing fears of "alien subversion". The WDU's messages found recipients among the middle and upper classes as well, broadening their voter base.[20]

Women played a new role in the early twentieth century, as was signalled in 1906 with the establishment of the Women's Unionist and Tariff Reform Association (WUTRA). When the Liberals failed to support women's suffrage, the Conservatives acted, especially by passing the Representation of the People Act 1918 and the Equal Franchise Act of 1928.[21] They realised that housewives were often conservative in outlook, were averse to the aggressive tone of socialist rhetoric, and supported imperialism and traditional values.[22] Conservatives claimed that they represented orderly politics, peace, and the interests of the ex-serviceman's family.[23] The 1928 Act added five million more women to the electoral roll and had the effect of making women a majority, 52.7%, of the electorate in the 1929 general election,[24] which was termed the "Flapper Election".[25]

A Neo-Tory movement flourished in the 1930s as part of a pan-European reaction against modernity. A network of right-wing intellectuals and allied politicians ridiculed democracy, liberalism and modern capitalism as degenerate. They warned against the emergence of a corporate state in Britain imposed from above. The intellectuals involved followed trends in Italy, France and especially Germany. The exchange of ideas with the continent was at first a source of inspiration, reassurance and hope. After Hitler's rise in 1933 it meant their downfall. War with Germany in 1939 ended British participation in transnational radical conservatism.[26]

Post-war consensus

During and after World War II, the Conservative Party made concessions to the social democratic policies enacted by the previous Labour government. This compromise was a pragmatic measure to regain power, but also the result of the early successes of central planning and state ownership forming a cross-party consensus. The conservative version was known as Butskellism, after the almost identical Keynesian policies of Rab Butler on behalf of the Conservatives and Hugh Gaitskell for Labour. The "post-war consensus" emerged as an all-party national government under Churchill, who promised Britons a better life after the war. Conservatives especially promoted educational reforms to reach a much larger population. The foundations of the post-war consensus was the Beveridge Report. This was a report by William Beveridge, a Liberal economist who in 1942 formulated the concept of a more comprehensive welfare state in Great Britain.[27] The report sought widespread reform by identifying the "five giants on the road of reconstruction": "Want… Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness".[28] In the report were labelled a number of recommendations: the appointment of a minister to control all the insurance schemes; a standard weekly payment by people in work as a contribution to the insurance fund; old age pensions, maternity grants, funeral grants, pensions for widows and for people injured at work; a new national health service to be established.

In the period between 1945 and 1970 (the years of the consensus), unemployment averaged less than 3%. The post-war consensus included a belief in Keynesian economics,[27] a mixed economy with the nationalisation of major industries, the establishment of the National Health Service and the creation of the modern welfare state in Britain. The policies were instituted by all governments, both Labour and Conservative, in the post-war period. The consensus has been held to characterise British politics until the economic crises of the 1970s (see Secondary banking crisis of 1973–1975) which led to the end of the post-war economic boom and the rise of monetarist economics. The roots of Keynes's economics, however, lie in a critique of the economics of the depression of the interwar period. Keynesianism encouraged a more active role of the government in order to "manage overall demand so that there was a balance between demand and output".[29]

The post-war consensus in favour of the welfare state forced conservative historians, typified by Herbert Butterfield, to re-examine British history. They were no longer optimistic about human nature, nor the possibility of progress, yet neither were they open to liberalism's emphasis on individualism. As a Christian, Butterfield could argue that God had decided the course of history but had not necessarily needed to reveal its meaning to historians. [30] Thanks to Iain Macleod, Edward Heath and Enoch Powell, special attention was paid to "One-nation conservatism" (coined by Disraeli) that promised support for the poorer and working-class elements in the Party coalition.[31]

Rise of Thatcherism

.jpg.webp)

However, in the 1980s, under the leadership of Margaret Thatcher, and the influence of Keith Joseph, there was a dramatic shift in the ideological direction of British conservatism, with a movement towards free-market economic policies and neoliberalism (commonly referred to as Thatcherism).[32] As one commentator explains, "The privatisation of state owned industries, unthinkable before, became commonplace [during Thatcher's government] and has now been imitated all over the world."[33] Thatcher was described as "a radical in a conservative party",[33] and her ideology has been seen as confronting "established institutions" and the "accepted beliefs of the elite",[33] both concepts incompatible with the traditional conception of conservatism as signifying support for the established order and existing social convention (status quo).[34]

Modern conservatism

Following a third consecutive general election defeat in 2005, the Conservative Party selected David Cameron as party leader, followed by Theresa May in 2016, both of whom have served as Prime Minister and sought to modernise and change the ideological position of British conservatism. From the 2010s to the present, the party has occupied a position on the right-wing of the political spectrum.[42]

In efforts to rebrand and increase the party's appeal, both leaders have adopted policies which align with liberal conservatism.[43][44] This has included a "greener" environmental and energy stance, and adoption of some socially liberal views. Some of these policies were thrust upon the party in the 2010–2015 coalition with the Liberal Democrats, such as acceptance of same-sex marriage, which the Liberal Democrat MP Lynne Featherstone initially put forward. The Prime Minister David Cameron gave all Conservative members a free vote, meaning that they would not be whipped for or against it (ultimately only 41% of Conservative members voted in favour). Many of these policies have been accompanied by a fiscal conservatism, in which they have maintained a hard stance on bringing down the deficit, and embarked upon a programme of economic austerity.

Other modern policies which align with one-nation conservatism[45] and Christian democracy[46][47] include education reform, extending student loan applicants to postgraduate applicants, and allowing those from poorer backgrounds to go further, whilst still increasing tuition fees and introducing a higher cap. There has also been an emphasis on human rights, in particular the European Convention on Human Rights,[48] whilst also supporting individual initiative.

The 2010s saw greater division within the Conservative Party, almost exclusively over Brexit and the direction of the Brexit negotiations. Ahead of the 2016 referendum on membership of the European Union, 184 of the 330 Conservative MPs (55.7%) backed Remain, compared to 218 of the 232 Labour MPs (97%), and all MPs from the SNP and Liberal Democrats. Following the vote to leave on the morning of 24 June, Cameron said that he would resign as Prime Minister, and was replaced by Theresa May. In 2019, two new parliamentary caucuses were formed; One Nation Conservatives and Blue Collar Conservatives.[49]

Conservative political parties in the United Kingdom

- Alliance EPP: European People's Party UK

- Christian Party

- Christian Peoples Alliance

- Conservative Party

- Democratic Unionist Party

- Britain First

- Reform UK

- UK Independence Party

- Ulster Unionist Party

- Veterans and People's Party

In British Overseas Territories

See also

Notes

- ↑ However, Burke lived before the terms "conservative" and "liberal" were used to describe political ideologies, and he dubbed his faction the "Old Whigs". cf. J. C. D. Clark, English Society, 1660–1832 (Cambridge University Press, 2000), p. 5, p. 301.

- ↑ See: One Nation Labour.

References

- ↑ D. Von Dehsen 1999, p. 36.

- ↑ Eccleshall 1990, p. 39.

- ↑ Dobson 2009, p. 73.

- 1 2 Lord Norton of Louth. Conservative Party. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ↑ Mehta, Binita (28 May 2015). "'You don't have to be white to vote right': Why young Asians are rebelling by turning Tory". The Telegraph. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ↑ Worthington, Glen, Conservatism in Australian National Politics, Parliament of Australia Parliamentary Library, 19 February 2002

- ↑ Anna Gambles, "Rethinking the politics of protection: Conservatism and the corn laws, 1830–52." English Historical Review 113.453 (1998): 928–952 online.

- ↑ Gregory Claeys, "Political Thought," in Chris Williams, ed., A Companion to 19th-Century Britain (2006). p 195

- ↑ Richmond & Smith 1998, p. 162.

- ↑ Auerbach, The Conservative Illusion. (1959), pp. 39–40

- ↑ Paterson 2001, pp. 93–94.

- ↑ Stephen Evans, "The Not So Odd Couple: Margaret Thatcher and One Nation Conservatism." Contemporary British History 23.1 (2009): 101–121.

- ↑ Eaton, George (27 May 2015). "Queen's Speech: Cameron's 'one nation' gloss can't mask the divisions to come". New Statesman. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ↑ Vail, Mark I. (18 November 2014). "Between One-Nation Toryism and Neoliberalism: The Dilemmas of British Conservatism and Britain's Evolving Place in Europe". JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies. 53 (1): 106–122. doi:10.1111/jcms.12206. S2CID 142652862.

- ↑ Hern, Alex (4 October 2012). "The 'one nation' supercut". New Statesman. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ↑ White, Michael (9 May 2015). "Cameron vows to rule UK as 'one nation' but Scottish question looms". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ↑ Chris Wrigley (2002). Winston Churchill: A Biographical Companion. ABC-CLIO. p. 123. ISBN 9780874369908.

- ↑ Andrew Roberts (2018). Churchill: Walking with Destiny. Penguin. p. 127. ISBN 9781101981016.

- ↑ David Thackeray, David. "Rethinking the Edwardian crisis of conservatism." Historical Journal (2011): 191–213 online.

- ↑ Alan Sykes, "Radical conservatism and the working classes in Edwardian England: the case of the Workers Defence Union." English Historical Review (1998): 1180–1209 online.

- ↑ David Jarvis, "Mrs Maggs and Betty: The Conservative Appeal to Women Voters in the 1920s." Twentieth Century British History 5.2 (1994): 129–152.

- ↑ Clarisse Berthezène and Julie Gottlieb, eds., Rethinking Right-Wing Women: Gender And The Conservative Party, 1880s To The Present (Manchester University Press, 2018).

- ↑ David Thackeray, "Building a peaceable party: masculine identities in British Conservative politics, c. 1903–24." Historical Research 85.230 (2012): 651–673.

- ↑ Heater, Derek (2006). Citizenship in Britain: A History. Edinburgh University Press. p. 145. ISBN 9780748626724.

- ↑ "The British General Election of 1929". CQ Researcher by CQ Press. Retrieved 2019-01-15.

- ↑ Bernhard Dietz, "The Neo-Tories and Europe: A Transnational History of British Radical Conservatism in the 1930s." Journal of Modern European History 15.1 (2017): 85–108.

- 1 2 Kenneth O. Morgan, Britain Since 1945: The People's Peace (2001), pp. 4, 6

- ↑ White, R. Clyde; Beveridge, William; Board, National Resources Planning (October 1943). "Social Insurance and Allied Services". American Sociological Review. 8 (5): 610. doi:10.2307/2085737. ISSN 0003-1224. JSTOR 2085737.

- ↑ Kavanagh, Dennis, Peter Morris, and Dennis Kavanagh. Consensus Politics from Attlee to Major. (Blackwell, 1994) p. 37.

- ↑ Reba N. Soffer, "The Conservative historical imagination in the twentieth century." Albion 28.1 (1996): 1–17.

- ↑ Robert Walsha, "The one nation group and one nation Conservatism, 1950–2002." Contemporary British History 17.2 (2003): 69–120.

- ↑ Scott-Samuel, Alex, et al. "The Impact of Thatcherism on Health and Well-Being in Britain." International Journal of Health Services 44.1 (2014): 53–71.

- 1 2 3 Davies, Stephen, Margaret Thatcher and the Rebirth of Conservatism, Ashbrook Center for Public Affairs, July 1993

- ↑ Wiktionary:conservatism

- ↑ Kerr, Peter; Hayton, Richard (June 2015). "Whatever Happened to Conservative Party Modernisation?" (PDF). British Politics. London: Palgrave Macmillan. 10 (2): 114–130. doi:10.1057/bp.2015.22. ISSN 1746-918X. S2CID 256510669.

...the financial crisis and the political instability it generated is not enough on its own to explain this turn to the right...there is a consensus throughout this issue that the party has emerged from this junction by steering itself along the road to the right

- ↑ Saini, Rima; Bankole, Michael; Begum, Neema (April 2023). "The 2022 Conservative Leadership Campaign and Post-racial Gatekeeping". Race & Class: 1–20. doi:10.1177/03063968231164599.

...the Conservative Party's history in incorporating ethnic minorities, and the recent post-racial turn within the party whereby increasing party diversity has coincided with an increasing turn to the Right

- ↑ Bale, Tim (March 2023). The Conservative Party After Brexit: Turmoil and Transformation. Cambridge: Polity. pp. 3–8, 291, et passim. ISBN 9781509546015. Retrieved 12 September 2023.

[...] rather than the installation of a supposedly more 'technocratic' cabinet halting and even reversing any transformation on the part of the Conservative Party from a mainstream centre-right formation into an ersatz radical right-wing populist outfit, it could just as easily accelerate and accentuate it. Of course, radical right-wing populist parties are about more than migration and, indeed, culture wars more generally. Typically, they also put a premium on charismatic leafership and, if in office, on the rights of the executive over other branches of government and any intermediate institutions. And this is exactly what we have seen from the Conservative Party since 2019

- ↑ de Geus, Roosmarijn A.; Shorrocks, Rosalind (2022). "Where Do Female Conservatives Stand? A Cross-National Analysis of the Issue Positions and Ideological Placement of Female Right-Wing Candidates". In Och, Malliga; Shames, Shauna; Cooperman, Rosalyn (eds.). Sell-Outs or Warriors for Change? A Comparative Look at Conservative Women in Politics in Democracies. Abingdon/New York: Routledge. pp. 1–29. ISBN 9781032346571.

right-wing parties are also increasing the presence of women within their ranks. Prominent female European leaders include Theresa May (until recently) and Angela Merkel, from the right-wing Conservative Party in the UK and the Christian Democratic Party in Germany respectively. This article examines the extent to which women in right-wing parties are similar to their male colleagues, or whether they have a set of distinctive opinions on a range of issues

- ↑ Alonso, José M.; Andrews, Rhys (September 2020). "Political Ideology and Social Services Contracting: Evidence from a Regression Discontinuity Design" (PDF). Public Administration Review. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. 80 (5): 743–754. doi:10.1111/puar.13177. S2CID 214198195.

In particular, there is a clear partisan division between the main left-wing party (Labour) and political parties with pronounced pro-market preferences, such as the right-wing Conservative Party

- ↑ Alzuabi, Raslan; Brown, Sarah; Taylor, Karl (October 2022). "Charitable behaviour and political affiliation: Evidence for the UK". Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics. Amsterdam: Elsevier. 100: 101917. doi:10.1016/j.socec.2022.101917.

...alignment to the Liberal Democrats (centre to left wing) and the Green Party (left wing) are positively associated with charitable behaviour at both the extensive and intensive margins, relative to being aligned with the right wing Conservative Party.

- ↑ Oleart, Alvaro (2021). "Framing TTIP in the UK". Framing TTIP in the European Public Spheres: Towards an Empowering Dissensus for EU Integration. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 153–177. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-53637-4_6. ISBN 978-3-030-53636-7. S2CID 229439399.

the right-wing Conservative Party in government supported TTIP...This logic reproduced also a government-opposition dynamic, whereby the right-wing Conservative Party championed the agreement

- ↑ [35][36][37][38][39][40][41]

- ↑ "BBC News – David Cameron: I am 'Liberal Conservative'". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-09-30.

- ↑ "Can Theresa May even sell her new conservatism to her own cabinet?". The Guardian. 2016-07-16. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2016-09-30.

- ↑ Quinn, Ben (2016-06-29). "Theresa May sets out 'one-nation Conservative' pitch for leadership". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2016-09-30.

- ↑ McGuinness, Damien (2016-07-13). "Is Theresa May the UK's Merkel?". BBC News. Retrieved 2016-09-30.

- ↑ ""From Big State to Big Society": Is British Conservatism becoming Christian Democratic? | Comment Magazine". www.cardus.ca. Retrieved 2016-09-30.

- ↑ "Where The Tory Leadership Candidates Stand On Human Rights – RightsInfo". 2016-07-04. Retrieved 2016-09-30.

- ↑ "Tory MPs launch rival campaign groups". BBC News. 2019-05-20. Retrieved 2020-03-25.

Bibliography

- D. Von Dehsen, Christian (1999). Philosophers and Religious Leaders. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-57356-152-5.

- Dobson, Andrew (2009). An Introduction to the Politics and Philosophy of José Ortega Y Gasset. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-12331-0.

- Eccleshall, Robert (1990). English Conservatism Since the Restoration: An Introduction & Anthology. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-04-445773-2.

- Paterson, David (2001). Liberalism and Conservatism, 1846-1905. Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-43-532737-8.

- Richmond, Charles; Smith, Paul (1998). The Self-Fashioning of Disraeli, 1818-1851. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52-149729-9.