Buccal pumping is "breathing with one's cheeks": a method of ventilation used in respiration in which the animal moves the floor of its mouth in a rhythmic manner that is externally apparent.[1] It is the sole means of inflating the lungs in amphibians.

There are two methods of buccal pumping, defined by the number of movements of the floor of the mouth needed to complete both inspiration and expiration.

Four stroke

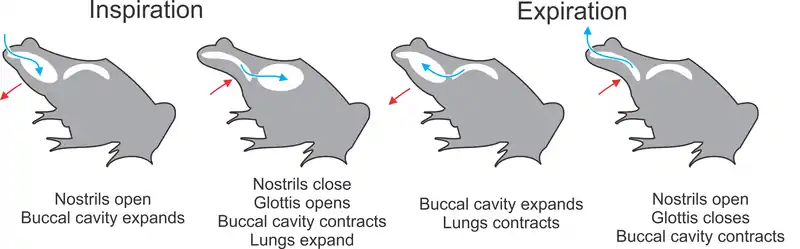

Four-stroke buccal pumping is used by some basal ray-finned fish and aquatic amphibians such as Xenopus and Amphiuma.[1] This method has several stages. These will be described for an animal starting with lungs in a deflated state: First, the glottis (opening to the lungs) is closed, and the nostrils are opened. The floor of the mouth is then depressed (lowered), drawing air in. The nostrils are then closed, the glottis opened, and the floor of mouth raised, forcing the air into the lungs for gas exchange. To deflate the lungs, the process is reversed.

Two stroke

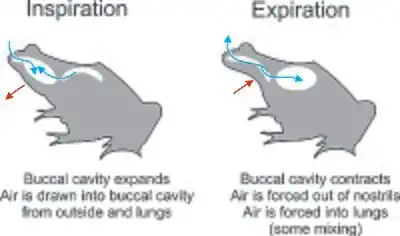

Two-stroke buccal pumping completes the process more quickly, as is seen in most extant amphibians.[1] In this method, the floor of the mouth is lowered, drawing air from both the outside and lungs into the buccal cavity. When the floor of the mouth is raised, the air is pushed out and into the lungs; the amount of mixing is generally small, about 20%.[2]

Gular pumping

Gular pumping refers to the same process, but accomplished by expanding and contracting the entire throat to pump air, rather than just relying upon the mouth.

This method of ventilation is inefficient, but is nonetheless used by all air-breathing amphibians and gular pumping is utilized to a varying extent by various reptile species.[3] Mammals, in contrast, use the thoracic diaphragm to inflate and deflate the lungs more directly. Manta ray embryos also breathe by buccal pumping, as mantas give live birth and embryos are not connected to their mother by umbilical cord or placenta as in many other animals.[4]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Brainerd, E. L. (1999). New perspectives on the evolution of lung ventilation mechanisms in vertebrates. Experimental Biology Online 4, 11-28. http://www.brown.edu/Departments/EEB/brainerd_lab/pdf/Brainerd-1999-EBO.pdf

- ↑ Brainerd, Elizabeth L. (1998-10-15). "Mechanics of Lung Ventilation in a Larval Salamander Ambystoma Tigrinum". Journal of Experimental Biology. 201 (20): 2891–2901. doi:10.1242/jeb.201.20.2891. ISSN 0022-0949.

- ↑ Owerkowicz, Tomasz; Colleen G. Farmer; James W. Hicks; Elizabeth L. Brainerd (4 June 1999). "Contribution of Gular Pumping to Lung Ventilation in Monitor Lizards". Science. 284 (5420): 1661–1663. Bibcode:1999Sci...284.1661O. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.486.481. doi:10.1126/science.284.5420.1661. PMID 10356394.

- ↑ Tomita, Taketeru; Minoru Toda; Keiichi Ueda; Senzo Uchida; Kazuhiro Nakaya (23 Oct 2012). "Live-bearing manta ray: how the embryo acquires oxygen without placenta and umbilical cord". Biology Letters. 8 (5): 721–724. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2012.0288. PMC 3440971. PMID 22675137.