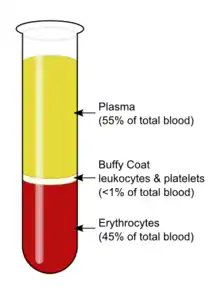

The buffy coat is the fraction of an anticoagulated blood sample that contains most of the white blood cells and platelets following centrifugation.[1]

Description

After centrifugation, one can distinguish a layer of clear fluid (the plasma), a layer of red fluid containing most of the red blood cells, and a thin layer in between. Composing less than 1% of the total volume of the blood sample, the buffy coat (so-called because it is usually buff in hue), contains most of the white blood cells and platelets.[2][3] The buffy coat is usually whitish in color, but is sometimes green if the blood sample contains large amounts of neutrophils, which are high in green-colored myeloperoxidase. The layer beneath the buffy coat contains granulocytes and red blood cells.

The buffy coat is commonly used for DNA extraction,[4] with white blood cells providing approximately 10 times more concentrated sources of nucleated cells.[5] They are extracted from the blood of mammals because mammalian red blood cells are anucleate and do not contain DNA. A common protocol is to store buffy coat specimens for future DNA isolation and these may remain in frozen storage for many years.[6]

Diagnostic uses

Quantitative buffy coat (QBC), based on the centrifugal stratification of blood components, is a laboratory test for the detection of malarial parasites, as well as of other blood parasites.[7]

The blood is taken in a QBC capillary tube which is coated with acridine orange (a fluorescent dye) and centrifuged; the fluorescing parasitized erythrocytes get concentrated in a layer which can then be observed by fluorescence microscopy,[7] under ultraviolet light at the interface between red blood cells and buffy coat. This test is more sensitive than the conventional thick smear and in over 90% of cases the species of parasite can also be identified.[8][9]

In cases of extremely low white blood cell count, it may be difficult to perform a manual differential of the various types of white cells, and it may be virtually impossible to obtain an automated differential. In such cases, the medical technologist may obtain a buffy coat, from which a blood smear is made. This smear contains a much higher number of white blood cells than whole blood.[10]

See also

References

- ↑ Cottler-Fox, Michele; Montgomery, Matthew; Theus, John (2009-01-01), Treleaven, Jennifer; Barrett, A John (eds.), "CHAPTER 24 - Collection and processing of marrow and blood hematopoietic stem cells", Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in Clinical Practice, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, pp. 249–256, ISBN 978-0-443-10147-2, retrieved 2022-08-09

- ↑ Mescher, Anthony L. (2018). "Blood". Junqueira's Basic Histology: Text and Atlas (15 ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. p. 237. ISBN 9781260026184.

- ↑ Marieb, Elaine N. (2007). Human Anatomy & Physiology (Seventh ed.). San Francisco: Pearson Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 978-0-8053-5910-7.

- ↑ Mychaleckyj, Josyf C; Farber, Emily A; Chmielewski, Jessica; Artale, Jamie; Light, Laney S; Bowden, Donald W; Hou, Xuanlin; Marcovina, Santica M (10 June 2011). "Buffy coat specimens remain viable as a DNA source for highly multiplexed genome-wide genetic tests after long term storage". Journal of Translational Medicine. 9: 91. doi:10.1186/1479-5876-9-91. ISSN 1479-5876. PMC 3128059. PMID 21663644.

- ↑ Fabre, Anne-Lise; Luis, Aurélie; Colotte, Marthe; Tuffet, Sophie; Bonnet, Jacques (30 November 2017). "High DNA stability in white blood cells and buffy coat lysates stored at ambient temperature under anoxic and anhydrous atmosphere". PLOS ONE. 12 (11): e0188547. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1288547F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0188547. PMC 5708797. PMID 29190767.

- ↑ Gustafson, Sarah; Proper, Jacqueline A.; Bowie, E. J. Walter; Sommer, Steve S. (1 September 1987). "Parameters affecting the yield of DNA from human blood". Analytical Biochemistry. 165 (2): 294–299. doi:10.1016/0003-2697(87)90272-7. ISSN 0003-2697. PMID 3425899.

- 1 2 Ahmed, Nishat Hussain; Samantaray, Jyotish Chandra (2014). "Quantitative Buffy Coat Analysis-An Effective Tool for Diagnosing Blood Parasites". Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 8 (4): DH01. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2014/7559.4258. ISSN 2249-782X. PMC 4064892. PMID 24959448.

- ↑ Sherman, Angel (2018). Medical Parasitology. EDTECH. ISBN 9781839473531.

- ↑ Kochareka, Manali; Sarkar, Sougat; Dasgupta, Debjani; Aigal, Umesh (October 2012). "A preliminary comparative report of quantitative buffy coat and modified quantitative buffy coat with peripheral blood smear in malaria diagnosis". Pathogens and Global Health. 106 (6): 335–339. doi:10.1179/2047773212Y.0000000024. PMC 4005131. PMID 23182137.

- ↑ Blumenreich, Martin S. (1990). The White Blood Cell and Differential Count (3rd ed.). Butterworths. ISBN 978-0-409-90077-4. PMID 21250104.

External links

- Blood Buffy Coat at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)