Cao Xueqin | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

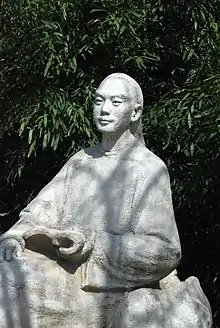

Statue of Cao Xueqin in Beijing | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 4 April 1710 Nanjing, China | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 10 June 1765 (aged 55) Beijing | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation | Novelist, poet, painter, philosopher | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 曹雪芹 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Courtesy name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 夢阮 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 梦阮 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Cáo Xuěqín ([tsʰǎʊ ɕɥètɕʰǐn] tsow sh'weh-chin; Chinese: 曹雪芹); (4 April 1710 — 10 June 1765)[1][2][3][4] was a Chinese novelist and poet during the Qing dynasty. He is best known as the author of Dream of the Red Chamber, one of the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature. His given name was Cáo Zhān (曹霑) and his courtesy name was Mèngruǎn (simplified Chinese: 梦阮; traditional Chinese: 夢阮).

Family

Cao Xueqin was born to a Han Chinese clan[5] that was brought into personal service (as booi aha or bondservants of Cigu Niru) to the Manchu royalty in the late 1610s.[6] His ancestors distinguished themselves through military service in the Plain White Banner (正白旗) of the Eight Banners and subsequently held posts as officials which brought both prestige and wealth.[7]

After the Plain White Banner was put under the direct jurisdiction of the Qing emperor, Cao's family began to serve in civil positions of the Imperial Household Department.

During the Kangxi Emperor's reign, the clan's prestige and power reached its height. Cao Xueqin's grandfather, Cao Yin (曹寅), was a childhood playmate to Kangxi while Cao Yin's mother, Lady Sun (孫氏), was Kangxi's wet nurse. Two years after his ascension, Kangxi appointed Cao Xueqin's great-grandfather, Cao Xi (曹璽), as the Commissioner of Imperial Textiles (織造) in Jiangning (present-day Nanjing), and the family relocated there.[8]

When Cao Xi died in 1684, Cao Yin, as Kangxi's personal confidant, took over the post. Cao Yin was one of the era's most prominent men of letters and a keen book collector. Jonathan Spence notes the strong Manchu element in the lives of these Imperial Household bond servants. They balanced the two cultures: Cao Yin took pleasure in horse riding and hunting and Manchu military culture, but was at the same time a sensitive interpreter of Chinese culture to the Manchus. By the early 18th century, the Cao clan had become so rich and influential as to be able to play host four times to the Kangxi Emperor in his six separate itinerant trips south to the Nanjing region. In 1705, the emperor ordered Cao Yin, himself a poet, to compile all surviving shi (lyric poems) from the Tang dynasty, which resulted in The Complete Poems of the Tang.[8]

When Cao Yin died in 1712, Kangxi passed the office over to Cao Yin's only son, Cao Yong (曹顒). Cao Yong died in 1715. Kangxi then allowed the family to adopt a paternal nephew, Cao Fu (曹頫), as Cao Yin's posthumous son to continue in that position. Hence the clan held the office of Imperial Textile Commissioner at Jiangning for three generations.

The family's fortunes lasted until Kangxi's death and the ascension of the Yongzheng Emperor to the throne. Yongzheng severely attacked the family and in 1727 confiscated their properties, while Cao Fu was thrown in jail.[7] This was ostensibly for their mismanagement of funds, though perhaps this purge was politically motivated. When Cao Fu was released a year later, the impoverished family was forced to relocate to Beijing. Cao Xueqin, still a young child, lived in poverty with his family.

Life

Almost no records of Cao's early childhood and adulthood have survived. Redology scholars are still debating Cao's exact date of birth, though he is known to have been around forty to fifty at his death.[9] Cao Xueqin was the son of either Cao Fu or Cao Yong.[10] It is known for certain that Cao Yong's only son was born posthumously in 1715; some Redologists believe this son might be Cao Xueqin. In the clan register (五慶堂曹氏宗譜), however, Cao Yong's only son was recorded as a certain Cao Tianyou (曹天佑). Further complicating matters for Redologists is the fact that neither the names Cao Zhan nor Cao Xueqin—names that his contemporaries knew him by—can be traced in the register.[11]

Most of what we know about Cao was passed down from his contemporaries and friends.[12] Cao eventually settled in the countryside west of Beijing where he lived the larger part of his later years in poverty selling off his paintings. Cao was recorded as an inveterate drinker. Friends and acquaintances recalled an intelligent, highly talented man who spent a decade working diligently on a work that must have been Dream of the Red Chamber. "Born in the prosperous, finally degenerate." Cao Xueqin's family fate has changed from the status like blooming of flowers to the state of decline, making him deeply experience the sorrow of life and the ruthlessness of the world, and also get rid of the mundanity and narrowness of his original social class. The trend of decadence also brought disillusionment and sentimentality. His tragic experience, his poetic emotion, his spirit of exploration, and his sense of innovation are all cast into "Dream of the Red Chamber". They praised both his stylish paintings, particularly of cliffs and rocks, and originality in poetry, which they likened to Li He's. Cao died some time in 1763 or 1764, leaving his novel in a very advanced stage of completion. (At least the first draft had been completed, some pages of the manuscript were lost after being borrowed by friends or relatives.) He was survived by a wife after the death of a son.

Cao achieved posthumous fame through his life's work. Dream of the Red Chamber is a vivid recreation of an illustrious family at its height and its subsequent downfall, and the novel was "semi-autobiographical" in nature.[13] A small group of close family and friends appeared to have been transcribing his manuscript when Cao died quite suddenly in 1763–4, apparently out of grief owing to the death of a son. Extant handwritten copies of this work—some 80 chapters—had been in circulation in Beijing shortly after Cao's death and scribal copies soon became prized collectors' items.

In 1791, Cheng Weiyuan (程偉元) and Gao E (高鶚), who claimed to have access to Cao's working papers, edited and published a "complete" 120-chapter version. This was its first woodblock print edition. Reprinted a year later with more revisions, this 120-chapter edition is the novel's most printed version. Many modern scholars question the authorship of the last 40 chapters of the novel, whether it was actually completed by Cao Xueqin.[2]

To this very day, Cao continues to be influential on new generations of Chinese novelists and poets, such as Middle Generation's An Qi, who paid homage to him in her poem To Cao Xueqin.[14]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The precise dating of Cao Xueqin's birth and death is a matter of heated debate amongst Chinese Redologists. It would be fair however to confine Cao's birth date to between 1715 and 1724, as attested by the elegiac poems by his friends – Duncheng (敦誠) and Zhang Yiquan (張宜泉) – which stated Cao was forty and nearly fifty respectively when he died. A much fuller discussion can be found under the relevant sections in Chen Weizhao's Hongxue Tongshi ("A History of Redology"), Shanghai People's Publishing Press, 2005, pp. 194–197; 348–349; 657–662.

- 1 2 Briggs, Asa (ed.) (1989) The Longman Encyclopedia, Longman, ISBN 0-582-91620-8

- ↑ Zhou, Ruchang. Cao Xueqin. pp. 230–233.

- ↑ Zhang Yiquan: Hong lou meng volume 1. p.2 cited in the introduction to The Dream of the Red Chamber. by Li-Tche Houa and Jacqueline Alézaïs.La Pléiade 1979

- ↑ Tanner, Harold Miles (2008). China: A history. Indianapolis, Ind.: Hackett. p. 363. ISBN 978-0-87220-915-2.

- ↑ This section summarises the more salient facts on Cao Xueqin's family as unearthed by 20th-century Redologists like Zhou Ruchang (周汝昌) and Feng Qiyong (馮其庸), which formed the basis of modern Redology. A detailed summary into the researches on Cao Xueqin's genealogy can be found, once again, in Chen, pp. 362–366; 681–687.

- 1 2 China: Five thousand years of history and civilization. Hong Kong: City University of Hong Kong Press. 2007. p. 722. ISBN 978-962-937-140-1.

- 1 2 Jonathan D. Spence. Ts'ao Yin and the K'ang-Hsi Emperor: Bondservant and Master. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965), esp. pp. 53–54, 157–165.

- ↑ See Note 1.

- ↑ Chen, pp. 190; 681–684

- ↑ Chen, pp. 345–346

- ↑ This paragraph is largely a summary of Chen, pp. 72–74.

- ↑ Allen, Tony; Grant, R. G.; Parker, Philip; Celtel, Kay; Kramer, Ann; Weeks, Marcus (June 2022). Timelines of World History (First American ed.). New York: DK. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-7440-5627-3.

- ↑ Ying, Li-hua (2010). "An Qi". Historical Dictionary of Modern Chinese Literature. The Scarecrow Press. p. 5.

References

- Liu, Shide, "Cao Xueqin". Encyclopedia of China, 1st ed.

- Chen, Weizhao, A History of Redology (Hongxue Tongshi), Shanghai People's Publishing Press, 2005. (《红学通史》, 陈维昭, 上海人民出版社, 2005年)

- Hummel, Arthur W. Sr., ed. (1943). . Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period. United States Government Printing Office.

External links

- Works by Xueqin Cao at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Cao Xueqin at Internet Archive

- Works by Cao Xueqin at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)