Castell Caer Seion at the summit of Conwy Mountain | |

Castell Caer Seion shown within Conwy | |

| Alternative name | Castell Caer Lleion, Castell Caer Leion, Conwy Mountain Hillfort, Sinnodune |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 53°16′57″N 3°51′44″W / 53.282512°N 3.862296°W |

| OS grid reference | SH 75938 77782 |

| Altitude | 244 m (801 ft) |

| Type | Hillfort |

| Width | 95 m (310 ft) |

| Volume | 30351 m² (326699 f²) |

| Diameter | 326 m (1069 ft) |

| History | |

| Material | Stone, earth |

| Founded | 6th–4th centuries BC (first phase), 3rd century BC (second phase) |

| Abandoned | 2nd century BC |

| Periods | Iron Age |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1906, 1909, 1951, 1952, 2008 |

| Archaeologists | H. Picton, W. Bezant Lowe, W .E. Griffiths & A. H. A. Hogg, George Smith |

| Condition | Ruined, but good. |

| Management | Cadw |

| Public access | Yes |

| Designation | Scheduled Ancient Monument |

Castell Caer Seion is an Iron Age hillfort situated at the top of Conwy Mountain, in Conwy County, North Wales. It is unusual for the fact that the main fort contains a smaller, more heavily defended fort, complete with its own distinct defences and entrance, with no obvious means of access between the two. The construction date of the original fort is still unknown, but recent excavations have revealed evidence of occupation as early as the 6th century BC, whilst the smaller fort can be dated with reasonable certainty to around the 4th century BC. Whilst the forts were constructed in different periods, archaeologists have uncovered evidence of concurrent occupation, seemingly up until around the 2nd century BC. The larger fort contained around 50 roundhouses during its lifetime, whereas examinations of the smaller fort have turned up no more than six.[1] The site was traditionally associated with Maelgwyn Gwynedd (c. 480 – c. 547 AD),[2] but there is no evidence pointing to a 6th-century occupation.[3] The fort and wider area beyond its boundaries have been said to retain significant archaeological potential, and are protected by law as a scheduled ancient monument.[2]

Description

The fort is on the summit of a ridge of rhyolite at an altitude of approximately 800 feet (244 m) and is enclosed by a single rampart, with more complex works protecting a smaller fortified area at the western end. The northern side of the ridge is steep enough to offer a natural defence meaning that no outer wall was needed for the first phase of construction.[3][4] The smaller fort was built inside the western margins of the larger fort sometime around the 4th century BC; it was completely enclosed, and defended by thick stone walls on all sides, with defensive ditches running along the eastern and north-eastern boundary and a defensive outwork to the southeast. The site has a commanding position overlooking Conwy Bay, and is situated close to a major trackway that follows the coastal ridge. The total area of the fort is 7.5 acres (3.0 ha), it is roughly 326 metres (1,070 ft) long, and at its widest measures around 95 metres (312 ft) from the southern ramparts to the cliffs on the northern boundary.[5]

Confusion surrounding name

Writing in Archaeologia Cambrensis, W.E. Griffiths and A. H. A. Hogg identify 'Caer Seion' as the older and more genuine name of the hillfort, for which they cite evidence dating as far back as the 9th century. The alternative name 'Castell Caer Lleion' seems to date to the late 17th century and probably came about due to a mistranslation. Indeed, 'Castell Caer' is somewhat of a tautology, translating into English as "Castle Fort".[6] Because there is no standardised name for the site, it is referred to variously as 'Caer Seion', 'Castell Caer Seion', 'Castell Caer Lleion', 'Castell Caer Leion' and 'Conwy Mountain hillfort'.[7]<[2][8] An antiquated name, no longer in popular use but recorded by John Leyland in his 1530s Itinerary in Wales, is 'Sinnodune'.[9]

Archaeological excavations

There have been three principal excavations at the site: first in 1906 and 1909, then in 1951 and 1952, and finally in 2008. The dearth of dateable finds meant that, until the early part of the 21st century, the dating of the site was largely inferential. Each excavation has revealed a little more about the site, with modern techniques enabling archaeologists to date the earliest known occupation of the fort to within 200 years.[10]

First excavation: 1906, 1909

The first recorded excavations – carried out by Harold Picton and W. Bezant Lowe – were begun in 1906, before a delay caused them to briefly abandon the project and resume it in 1909. Their excavations revealed little, but they are the first to record finding sling stones at the site, and they also turned up a rubbing stone. Bezant Lowe noted the possible existence of a semi-circular defence facing the entrance to the smaller fort.[11] In one of the huts at the south-western end of the small fort they uncovered a stone floor, haphazard for the most part, but carefully laid and fitted together at one side of the hut. Picton notes that there was no evidence of the floor being used as a hearth, but does not speculate further as to the nature of the feature.[12]

Second excavation: 1951, 1952

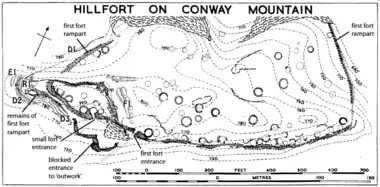

By far the most extensive of the excavations were those conducted on behalf of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales. Most of what we now know about the site stems from these digs, carried out by W.E. Griffiths and A.H.A. Hogg. They concluded that the site showed two periods of fortification, both within the latter part of the pre-Roman Iron Age. Whilst we now know that the fort was occupied as early as the Early to Middle Iron Age, the archaeologists did note at the time that their evidence for dating was slight; and for structural development was 'largely inferential'. They were the first to provide evidence that the two forts were designed to be used concurrently, based on the layout of the walls at the juncture of the two enclosures, and also speculate that the two separate enclosures were accessible to each other via some form of moveable ladder. No direct evidence exists to support this, but Griffiths and Hogg thought it likely because of the existence of a level causeway leading through the eastern defensive ditch to the northern corner of the small enclosure, where there were no entrances. (See F1 on the annotated plan; this feature is also clearly visible on the image in the infobox.)

Third excavation: 2008

The third excavation was small in scale, but important for being able to offer definitive dating evidence pertaining to the occupation of the two forts. It was carried out by George Smith of the Gwynedd Archaeological Trust, on behalf of Cadw, with environmental reports by Astrid E. Caseldine and Catherine Griffiths from the University of Wales. They were inspired to carry out this undertaking because of a 1991 survey (and subsequent report) by the Snowdonia National Park Authority, which remarked that the 1956 excavation had identified charcoal-rich layers that could be targeted for future research. The excavation and radiocarbon analysis of this charcoal allowed the team to place the earliest known occupation of the original fort at somewhere between the 6th and 4th centuries BC, and the construction of smaller fort around the 4th century BC. These investigations were not able to date the construction of the original fort, but did put the known occupation of the site back by a number of centuries, whilst also suggesting it was abandoned sometime before the 2nd century BC.[13] This would render a popular theory, that the fort was torn down as a result of the Roman invasion of Wales in 48 AD, unlikely. Analysis of pollen, grain and wood also allowed reasonable speculation to be made as to the likely diet and occupation of the fort's inhabitants, and also to the make-up of the wider landscape. (See "Environment" for further details.)

Huts

Only a small number of the more than 50 roundhouses known to have existed on site have ever been archaeologically excavated. The style of these huts seems largely contiguous throughout the two periods of the fort construction, with a general similarity in size and material found within. This contrasts with other sites which had occupation (or reoccupation) throughout the Roman period and beyond, where a distinct mix of architectural styles and hut shapes can often be observed. The roofing arrangements do, however, show some development on the site, with the dearth of post holes in the huts dated to the first period (Huts 1 and 3) suggesting some kind of wigwam roofing, whereas the hut that was examined from the later period (Hut 4) shows evidence of two systems of roof timbering involving internal posts. Many of the huts lay along a terrace behind the main southern rampart, where it has been speculated that the inhabitants would have been protected from the wind.[14]

Entrances

Three definite entrances were identified at the site, with another possible one speculated, but not confirmed. The only one to be examined fully was the main entrance to the earlier fort, whilst the other two were cleared of recent additions and surveyed in less detail.

Main entrance

The main entrance, located in the southern rampart slightly to the east of Hut 1, was 17 feet long and 8.6 inches at its narrowest point (see 'first fort entrance' on the annotated plan). The entrance appears to have been paved at one time, but the stones have now eroded and only slight traces remain. The thickened rampart of the outside entrance was supported by a plinth of large, flat blocks, set into a foundation trench, which extended 17 feet to the East; and sat flush with the surface of the subsoil, suggesting it would have been invisible when in contemporary use. This plinth was necessary to support the heavier parts of the rampart on the slope of the ground to the south. It is likely that four large, square post holes found at the East and West sides of the entrance passage, belonged to a wooden bridge over the gateway; and would have supported the (likely timber)[15] gate itself, probably on a pair of outer posts. The gate opening was 6 feet wide and could therefore have been secured by a single door.

Entrance to the smaller fort

Little is known about the entrance to the smaller fort as it has not been fully excavated, but the existence of large, square post holes similar to those found in the main entrance suggest that they probably served the same function as those found in the entrance to the main fort. The only notable difference was their location, with the post holes being situated not inside the passage itself, but around the corner of the passage, against the inner rampart.

Outwork entrance

The third entrance was in the defensive outwork structure located at the south-east of the site, (see 'blocked entrance to outwork' on the annotated plan). Minimal investigation was made of this feature, but enough to establish that it formed a passage about 19 feet wide and 23 feet long, set between the overlapping ends of the ramparts and faced with orthostats (a large stone with a more or less slab-like shape), some of which have been described as 'almost megalithic in character'. The North side had collapsed, blocking the entrance, but the archaeologists speculated that it must have been an impressive structure in its original form, and possibly designed with this effect in mind.[16][4]

Defences

The main defences of both forts were stone-built walls of varying construction, sometimes accompanied on their outer side with a ditch. The larger fort remained almost unchanged during its lifetime and was protected by a single wall which enclosed the site on the three accessible sides, following the best natural line for defence. The smaller fort had two distinct periods of construction and was more strongly fortified than the main enclosure; its original incarnation being larger and more elaborately fortified, than its latter. Whilst most structural details of the site were simple, the defences of the small fort were particularly unusual in the context of other Iron Age hillforts, as they were designed to be defended against the inside of the main enclosure, as well as from outside attack.

Primary rampart

The primary rampart which enclosed the site on three sides (East, South and West), was said to follow a 'sinuous' course along the hill top, 'selecting the line most suitable for defence'. The outer southward face of this rampart was described as being much ruined, about 10 feet thick, built of fairly large stones, and potentially containing a number of slabs laid on edge. The inner face was built partly of laid masonry and partly of slabs laid on edge; the slabs were differing sizes but some are described as 'very large'. Around the entrance to the larger fort the rampart is noted as having double-facing, and further along to the east the outer face of the rampart is described as being well-preserved, with a pronounced batter (meaning it was deliberately constructed with a receding slope for stability). The steep cliffs to the North and north-east meant that no extra defences were needed on that side of the fort, but where the incline is shallower to the north-west, the remains of a rampart could be traced. It was described as much ruined and overgrown with turf, and the investigators could not make out its construction, although they did note an additional defensive ditch along its outside face (marked on the annotated map as D1). This ditch extended the length of the rampart and continued to the south-west, around a rocky outcrop at the extreme West of the site (see D2).

Small fortress

The south wall of the small enclosure was measured as being wider than that of the original rampart, being estimated at 12–16 feet thick; and built of laid masonry. Outside the south-west wall of the small fort, an additional defensive wall was examined and found to end on a rock outcrop at the westernmost point of the site (see R1 on map). The defensive ditch which followed the north-west rampart of the main fort, carried on around this wall, and where it rounded the western outcrop, there was clear evidence that a smaller, additional ditch had been cut (see E1). The larger of the ditches continued parallel to the southern wall of the smaller fort, ending just in front of the defensive outwork (see D3). Inside the large fort, and running parallel to the eastern wall of the small fort was an additional bank-and-ditch defence combination, which was interrupted by low causeways (see F1).

Outwork

The outwork was notable for the fact that it was constructed in a different fashion to the other walls on the site, being faced by large blocks laid flat – or as was the case near the entrance – with slabs on edge; and filled with small stones and earth.

Huts associated with defence

Two huts were also associated with the defences; hut 1 because of its location just inside the entrance to the larger fort, and also the hut adjoining hut 3 on its east, for the same reason. Bolstering this theory is the fact that in hut 1 the investigators found 612 sling stones, half of which lay stacked in a neat pile against the inner face of the south-east wall, suggesting their likely use as a defensive arsenal. Whilst the hut immediately to the East of hut 3 was not actually examined by the archaeologists; the discovery of a number of sling stones by Picton and Bezant Lowe at this site in 1909, somewhat corroborates this speculation.[16][4]

Material finds

The site has yielded many small material finds which helped early archaeologists date the fort to the Iron Age period, in the absence of any datable pottery. Among the more notable finds were 1,141 sling stones, in the shape of smooth, oval beach pebbles, 1–2 inches long (about half of which were found together in a neat pile against the inner face of the hut wall) – a possible pair of iron tweezers, and a probable lignite spindlewhorl; which are found rarely in Britain. A small fragment of corroded iron has also been suggested as a possible lancehead, or knife. A number of stone spindlewhorls were also found, along with a total of four saddle querns, some rubbing stones, hones (or whetstones), various pot boilers and some stones of uncertain use. Among the identifiable bone fragments uncovered, were those of ox, horse and sheep.[17]

Environment

Analysis of pollen indicated that the area in and immediately around the fort was a heath and grass dominated environment, much the same as is in existence today; whilst pollen and charcoal analysis suggest it likely that the site existed close to a woodland containing hazel, birch and alder.

References

- ↑ Smith, George (22 August 2012). "RE-ASSESSMENT OF TWO HILLFORTS IN NORTH WALES: PEN-Y-DINAS, LLANDUDNO AND CAER SEION, CONWY" (PDF). Archaeology in Wales: 8–15. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 Cadw. "Castell Caer Lleion (CN012)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- 1 2 An Inventory of the Ancient Monuments in Caernarvonshire: I East: the Cantref of Arllechwedd and the Commote of Creuddyn, Volume 2. The Royal Commission On Ancient Historical Monuments in Wales and Monmouthshire. 1960. pp. 70–72. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 "This text is reproduced under the Non-Commercial Government Licence for public sector information".

- ↑ Smith, George (22 August 2012). "RE-ASSESSMENT OF TWO HILLFORTS IN NORTH WALES: PEN-Y-DINAS, LLANDUDNO AND CAER SEION, CONWY" (PDF). Archaeology in Wales: 8–15. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ↑ W.E. Griffiths, A.H.A. Hogg (1956). "The Hillfort on Conway Mountain, Caernarvonshire". Archaeologia Cambrensis, Journal of the Cambrian Archaeological Association. 105: 49. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ "Castell Caer Seion;castell Caer Leion, Conwy Mountain (95279)". Coflein. RCAHMW. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ "Snowdonia Heritage". Snowdonia Heritage. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ Leland, John (1539). Leland's Itinerary in Wales. p. 84. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ Smith, George (22 August 2012). "RE-ASSESSMENT OF TWO HILLFORTS IN NORTH WALES: PEN-Y-DINAS, LLANDUDNO AND CAER SEION, CONWY" (PDF). Archaeology in Wales: 8–15. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ↑ "Hill Fort On Conway Mountain, Caernarvonshir". Archaeologia Cambrensis. 105: 56. June 1956 – via Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru – The National Library of Wales.

- ↑ Harold Picton, W. Bezant Lowe (June 1909). "Journal of Cambrian Archaeology". Archaeologia Cambrensis. Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru – The National Library of Wales. 9 (6th Series): 500–504. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ Smith, George (22 August 2012). "RE-ASSESSMENT OF TWO HILLFORTS IN NORTH WALES: PEN-Y-DINAS, LLANDUDNO AND CAER SEION, CONWY" (PDF). Archaeology in Wales: 8–15. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ↑ "Hill Fort On Conway Mountain, Caernarvonshire". Archaeologia Cambrensis. 105: 49–80. June 1956 – via Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru – The National Library of Wales.

- ↑ "The Iron Age: Architecture". From Dot to Domesday. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- 1 2 "The Hill Fort at Conway Mountain, Caernarvonshire". Archaeologia Cambrensis. Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru – The National Library of Wales. 105: 63. 1956. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ "Archaeologia Cambrensis, Journal of the Cambrian Archaeological Association". 105. Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru – The National Library of Wales. 1956: 76–80.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)