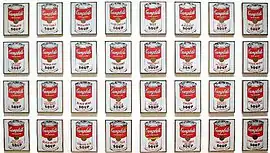

| Campbell's Soup Cans | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Andy Warhol |

| Year | 1962 |

| Catalogue | 79809 |

| Medium | Synthetic polymer paint on canvas |

| Dimensions | 20 by 16 inches (51 cm × 41 cm) each for 32 canvases |

| Location | Museum of Modern Art. Acquired from Irving Blum in 1996, New York (32 canvas series displayed by year of introduction) |

| Accession | 476.1996.1–32 |

Campbell's Soup Cans[1] (sometimes referred to as 32 Campbell's Soup Cans)[2] is a work of art produced between November 1961 and June 1962[3][4] by American artist Andy Warhol. It consists of thirty-two canvases, each measuring 20 inches (51 cm) in height × 16 inches (41 cm) in width and each consisting of a painting of a Campbell's Soup can—one of each of the canned soup varieties the company offered at the time.[1] The works were Warhol's hand-painted depictions of printed imagery deriving from commercial products and popular culture and belong to the pop art movement.

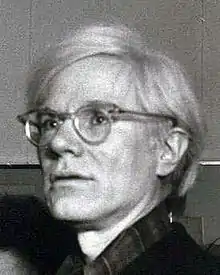

Warhol was a commercial illustrator before embarking on painting. Campbell's Soup Cans was shown on July 9, 1962, in Warhol's first one-man gallery exhibition[5][6] at the Ferus Gallery of Los Angeles, California, curated by Irving Blum. The exhibition marked the West Coast debut of pop art.[7] Blum owned and possessed the painting series until he loaned it to the National Gallery of Art for several years in 1987 and then sold it to the Museum of Modern Art in 1996. The subject matter initially caused offense, in part for its affront to the technique and philosophy of the earlier art movement of abstract expressionism. Warhol's motives as an artist were questioned. Warhol's association with the subject led to his name becoming synonymous with the Campbell's Soup Can paintings.

Warhol produced a wide variety of art works depicting Campbell's Soup cans during three distinct phases of his career, and he produced other works using a variety of images from the world of commerce and mass media. After considering litigation, the Campbell Soup Company embraced Warhol's Campbell's Soup cans theme. Today, the Campbell's Soup cans theme is generally used in reference to the original set of 32 canvases, but it also refers to other Warhol productions: approximately 20 similar Campbell's Soup painting variations also made in the early 1960s; 20 3 feet (91 cm) in height × 2 feet (61 cm) in width, multi-colored canvases from 1965; related Campbell's Soup drawings, sketches, and stencils over the years; two different 250-count 10–element sets of screen prints produced in 1968 and 1969; and other inverted/reversed Campbell's Soup can painting variations in the 1970s. Because of the eventual popularity of the entire series of similarly themed works, Warhol's reputation grew to the point where he was not only the most-renowned American pop-art artist,[8] but also the highest-priced living American artist.[9]

There is some confusion because sometimes the later screen print sets are referred to as if they are the Campbell's Soup Can set, and sometimes the original set of painting canvases is referred to as if it is a set of screenprints. In addition, there is ongoing production and sale of unauthorized screen prints, of what is legally Warhol's intellectual property, as a result of a fallout with former employees. There are also varied explanations for this theme. The popular explanation of his choice of the Campbell's Soup cans theme is that one artistic acquaintance inspired the original series with a suggestion that brought him closer to his roots. There are other artists who are said to have also influenced the pursuit of this theme.

Early career

New York art scene

Warhol arrived in New York City in 1949, directly from the School of Fine Arts at the Carnegie Institute of Technology,[10] and he quickly achieved success as a commercial illustrator. His first published drawing appeared in the Summer 1949 issue of Glamour Magazine.[11] In 1952, he had his first art gallery show at the Bodley Gallery with a display of Truman Capote–inspired works.[12] By 1955, with the hired assistance of Nathan Gluck, Warhol was tracing photographs borrowed from the New York Public Library's photo collection and reproducing them with a process he had developed earlier as a collegian at Carnegie Tech. His process, which foreshadowed his later work, involved pressing wet ink illustrations against adjoining paper.[13] During the 1950s, he had regular showings of his drawings, and exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art (Recent Drawings, 1956).[10]

Pop art

In 1960, Warhol began producing his first canvases, which he based on comic strip subjects.[14] Although Warhol had produced silkscreens of comic strips and other pop art subjects, he supposedly confined himself at the time to soup cans as a subject in order to avoid competing with the more finished style of comics done by Roy Lichtenstein.[15] Warhol once said, "I've got to do something that really will have a lot of impacts that will be different enough from Lichtenstein and James Rosenquist, that will be very personal, that won't look like I'm doing exactly what they're doing."[16]

In 1961, Warhol was wavering between the action painting of abstract expressionisms, with its use of drips and brushstrokes, and the more direct style of pop art. Most of his early soup-can work tended toward the latter. He experimented with hand painting and spray painting through a stencil cutout, as well as rubber stamping images. In January 1962, he began stamping with engraved art gum erasers onto canvas and paper, using acrylic paint.[17]

Some sources mistakenly claim that the original set of 32 Campbell's Soup cans was a set of silkscreen works.[18] There is so much confusion on what the Campbell's Soup cans are that when the Art Gallery of Ontario acquired a Campbell's Soup I set, The Globe and Mail described it as "the entire, iconic series".[19] The Museum of Modern Art, which now owns the 32 Campbell's Soup Cans, as well as complete sets of Campbell's Soup I and Campbell's Soup Cans II, describes the first as a set of paintings ("Acrylic with metallic enamel paint on canvas, 32 panels")[1] and the latter two as sets of screenprints ("Porfolio of ten screenprints").[20][21] The original 32 soup-can works were produced by tracing projections of soup cans onto canvas, followed by hand brushstrokes.[22] The process relied on stamps and stencils, which were Warhol's intermediate step from painterly techniques to silkscreening.[23] They are regarded as one "of the works on which his fame as an artist rests",[24] as well as a necessary part of "any true retrospective exhibition of his work".[25]

Warhol was able to get exposure for his comic strip (and newspaper ad) paintings by using them as a backdrop for his Bonwit Teller window design in April 1961.[26] Leo Castelli visited Warhol's gallery in 1961 and said that the work he saw there was too similar to Lichtenstein's,[27][28] although Warhol's and Lichtenstein's comic artwork differed in subject matter and techniques (e.g., Warhol's comic-strip figures were humorous pop-culture caricatures, such as of Popeye, while Lichtenstein's were generally of stereotypical hero and heroines and were inspired by comic strips devoted to adventure and romance).[29] Castelli chose not to represent both artists at that time. (He would, in November 1964, be exhibiting Warhol, his Flower Paintings, and then Warhol again in 1966.[30]) In February 1962, Lichtenstein displayed at a sold-out exhibition of cartoon pictures at Castelli's eponymous Leo Castelli Gallery, ending the possibility of Warhol exhibiting his own cartoon paintings.[31] Lichtenstein's 1962 show was quickly followed by Wayne Thiebaud's April 17, 1962, one-man show at the Allan Stone Gallery, featuring all-American foods, which irritated Warhol, who felt it jeopardized his own food-related works.[32] Warhol was considering returning to the Bodley gallery, but Bodley's director did not like his pop artworks.[16] In 1961, Warhol was offered a three-man show, by Allan Stone at his 18 East 82nd Street Gallery, with Rosenquist and Robert Indiana; but all three were insulted by this proposition.[33]

By March 1962, art critic David Bourdon had seen some of Warhol's soup cans illustrated in a newsletter visited his social space/studio.[34] Irving Blum was the first dealer to show Warhol's soup can paintings.[5] In December 1961, he happened to be visiting Warhol at his 1342 Lexington Avenue apartment/art studio[35][36] and then, in May 1962, at a time when Warhol was being featured in a May 11, 1962, Time magazine article "The Slice-of-Cake School",[37] along with Lichtenstein, Rosenquist, and Thiebaud.[38] That article included an April 1962 photo of Warhol eating Campbell's Soup straight out of an upside down can while standing next to a human-sized canvas of a Campbell's Soup Can painting.[39][40] Warhol, who was interviewed on April 24,[40] was the only artist whose photograph actually appeared in the article, which is indicative of his knack for manipulating the mass media.[41] He was also a bit of a surprise choice over Claes Oldenburg, Jim Dine, Tom Wesselmann, and George Segal, who had already presented pop art shows that had been reviewed.[40] Blum saw dozens of Campbell's Soup can variations, including a grid of One-Hundred Soup Cans that day.[15] By the time of Blum's May 1962 visit, Warhol was working on his 16th individual realistic soup can portrait of the 32-can series; and the May Time article noted that he was "currently occupied with a series of 'portraits' of Camplell's soup cans in living colour", with Warhol quoted as saying, "I just paint things I always thought were beautiful, things you use every day and never think about...I'm working on soup...I just do it because I like it."[4] Three of the Campbell's Soup Can paintings were laid out on Warhol's parquet floor.[42] Blum, who knew that some of Warhol's larger Campbell's Soup can works were already being marketed by New York City art dealers,[42] was shocked that Warhol had no gallery arrangement and offered him a July show at the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles. This would be Warhol's first one-man show of his pop art.[5][6] Warhol was assured by Blum that the newly founded Artforum magazine, which had an office above the gallery, would cover the show. Not only was the show Warhol's first solo gallery exhibit, but it was considered to be the West Coast premiere of pop art.[7] Blum also used the lure of Hollywood celebrity to entice Warhol to exhibit out west, despite Warhol's interest in the New York fine arts scene.[43] Warhol's fans Dennis Hopper and Brooke Hayward (Hopper's wife at the time) held a welcoming party for the event to help Warhol meet West Coast artists and celebrities.[44][45] A letter from Blum to Warhol dated June 9, 1962, set the exhibition opening for July 9.[46]

Premiere

Warhol sent Blum thirty-two 20-by-16-inch (510 mm × 410 mm) canvases of Campbell's Soup can portraits, each representing a particular variety of the Campbell's Soup flavors available at the time.[1] A postcard dated June 26, 1962, sent by Irving Blum states, "32 ptgs arrived safely and look beautiful. strongly advise maintaining a low price level during initial exposure here".[47] The thirty-two canvases are very similar: each is a realistic depiction of the iconic, mostly red and white Campbell's Soup can silkscreened onto a white background.[48] If they could become lasting, they would recall the time in 1962 when Campbell's had exactly 32 varieties. "So it kind of marks a time", according to Warhol.[49]

The Ferus exhibition opened on July 9, 1962, with Warhol absent and without a formal opening.[50] However, the opening coincided with La Cienega Boulevard's "Monday Art Walk", which was a popular event.[51] The thirty-two single soup-can canvases were placed in a single line, much like products on shelves, each displayed on narrow individual ledges.[52] The contemporary impact was slight, but the historical impact is considered today to have been a watershed. The gallery audience was unsure what to make of the exhibit. A John Coplans Artforum article, which was in part spurred on by a corresponding display of dozens of soup cans by a nearby gallery with a display advertising them at three for 60 cents ($5.8 in 2022), encouraged people to take a stand on Warhol.[53][54] Another detractor, the nearby Primus Stuart Gallery, stacked a pyramid of real Campbell's Soup cans in the window below a sign that read "Do Not Be Misled. Get the Original. Our Low Price 2—0.33¢." ($3.19 in 2022).[51][55] The Los Angeles Times published a cartoon where two characters mocked the artistic impression that the paintings gave.[55] Few actually saw the paintings at the Los Angeles exhibit or at Warhol's studio, but word spread, as controversy and scandal, due to the work's seeming attempt to replicate the appearance of manufactured objects.[56] Extended debate on the merits and ethics of focusing one's efforts on such a mundane commercial, inanimate object kept Warhol's work at the center of art world conversations. The pundits could not believe an artist would reduce art to the equivalent of a trip to the local grocery store. Talk did not translate into monetary success for Warhol. Dennis Hopper was the first of only a half dozen to pay $100 ($967.44 in 2022) for a canvas. Blum decided to try to keep the thirty-two canvases as an intact set and bought back the few sold; only 2 paintings had been taken home and 4 had been put on reserve.[57] This pleased Warhol, who had conceived of them as a set, and he agreed to sell the set for ten monthly $100 installments to Blum.[58][53] Those payments were twice what Blum was paying in rent at the time.[59] Warhol had passed a milestone with this, his first serious art show.[60] Blake Gopnik describes the result as not "...bad for radical new pictures in an unknown and weirdly repetitive style by an artist with zero name recognition and no local ties."[59] An alternate story, from Blum's business partner Joseph Helman, is that Blum had committed to giving Warhol a commission of $3000 ($29023.1 in 2022), based on a $200 ($1934.87 in 2022) price-per-canvas; and the final $1000 payment was the result of heated renegotiation.[59]

The exhibition closed on August 4, 1962, the day before Marilyn Monroe's death. Warhol went on to purchase a Monroe publicity still from the film Niagara, which he later cropped and used to create one of his most well-known works: his painting of Marilyn. Although Warhol continued painting other pop art, including Martinson's coffee cans, Coca-Cola bottles, S&H Green Stamps, and other Campbell's Soup cans, he soon became known to many as the artist who painted celebrities. In October 1963, he returned to Blum's gallery to exhibit Elvis and Liz.[5]

Blum had to buy back a total of 5 or 6 paintings, depending on the source, before paying Warhol for the complete set.[59][61] He retained possession of the work for over 25 years, generally keeping them in the original special slotted crate, except for the occasional home display in his own dining room.[43]

Although the original exhibition of the set presented them all at the same height on various walls, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) generally presented them in a grid on a single wall (see main image above), except for the 2015 Warhol exhibition that it hosted.[62] Since Blum was not able to hang the paintings in a straight line with the proper spacing and perspective, he installed shelves to make the exhibition spacing and placement easier.[63] Since Warhol gave no indication of a definitive ordering of the collection, the sequence chosen by MoMA (in the picture at the upper right of this article), for the display from their permanent collection, reflects the chronological order in which the varieties were introduced by the Campbell Soup Company, beginning with Tomato, which debuted in 1897, in the upper left.[1] By April 2011, the curators at MoMA had reordered the varieties, moving Clam Chowder to the upper left and Tomato to the bottom of the four rows.[1] Blum had installed them in a 4-row grid when displayed in his own dining room prior to his making them available them for public display.[43]

Subsequent publicity

In August, Warhol's pop art had its first museum presentation in a survey show at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut. This show resulted in Warhol's first fine-art review in The New York Times. Regarding some of Warhol's Campbell's Soup can paintings, the review stated, "These are no mere unruly incidents but big steps towards art that is socially to the point."[64]

Although an early review announced that Warhol was to have a gallery arrangement with Martha Jackson in New York (along with Willem de Kooning, Adolph Gottlieb, Oldenburg, and Dine), Jackson sent word that she was canceling a promised December exhibition, noting "The introduction of your paintings has already had very bad repercussions for us."[65] News of her cancellation came before the Ferus exhibition ended.[60] Even though she cancelled his exhibition, her assistant John Weber sold ten Warhol paintings that she had taken on consignment.[66]

In August, when Sidney Janis invited Warhol to present as part of the Sidney Janis Gallery's late October exhibition entitled "The New Realists: An Exhibition of Factual Painting & Sculpture", it was still unclear to Janis if Warhol's preferred referent was Andy or Andrew.[67] Warhol exhibited a canvas with 200 soup cans (200 Soup Cans) and another that presented a human-sized Beef Noodle Soup (Big Campbell's Soup Can), as well as 19¢ and Do It Yourself (Flowers) alongside works by Oldenburg, Lichtenstein, and others.[68][67] The New Yorker said the exhibition "hit the New York art world with the force of an earthquake. Within a week tremors had spread to art centers throughout the country." A Kansas City newspaper ran the headline "Which Way Is Modern Art Going? Hold Your Breath and Watch the Soup Cans".[67]

After Jackson cast Warhol aside, Emile de Antonio brought Warhol and his ex-girlfriend, Eleanor Ward, together. After a bit of encouragement and drinking, Ward said that if Warhol would paint her a two-dollar bill she would give him a show.[69] Warhol's first New York solo Pop exhibit opened at Ward's Stable Gallery on November 6, 1962.[70] The exhibit included Marilyn Diptych, but no soup cans were on display, even though they were on guest badges.[71] Warhol's invitations to the exhibit included a quote from a college art student's perception of the message Warhol's soup can paintings conveyed: "I love soup, and I love it when other people love soup too, because then we can all love it together and love each other at the same time."[72] Warhol earned important praise for this exhibition, including from Michael Fried, who had been harsh with him 12 years earlier.[70]

Campbell's Soup Company

Can and label history

What became the Campbell's Soup Company was started in 1869 by Joseph A. Campbell, a fruit merchant from Bridgeton, New Jersey, and Abraham Anderson, an icebox manufacturer from South Jersey.[73] Although Anderson left the company in 1876, his son, Campbell Speelman, remained at Campbell's as a creative director and designed the original Campbell's Soup cans.[74] In 1894, Arthur Dorrance became the company president.[75] In 1897, John T. Dorrance, a nephew of company president Dorrance, began working for the company.[76][77] In 1897, Dorrance, a chemist, developed a commercially viable method for condensing soup, leading to the famous label's origin in 1898.[73][78] In the 21st century, the label continued to retain elements of the 1898 design, such as the oddly tilted letter "O" in the word Soup, and the gold medal that was added in 1900.[79][80] The original label was inspired by the Cornell Big Red football team uniforms.[43] When Campbell's Soup Cans was presented in 1962, the Campbell's soup can label had not changed in the previous 50 years.[81]

Relation to Warhol's art

Although it would be widely announced in the May 1962 issue of Time magazine,[4] as late as March 1962 Warhol sought secrecy for his Campbell's Soup project, stating his hope "that the Campbell Soup Co. knows nothing about these paintings; the whole point would be lost with any kind of commercial tie-in."[82] During the first week of the July 1962 Ferus Gallery exhibition, Campbell's Soup CEO William Murphy sent a team of legal representatives to evaluate the "use and violation of trademarks".[61] Initially, Campbell Soup Company considered legal action, but decided to evaluate the public reaction to the art first.[83] Within months of the original 1962 exhibition, Campbell's Soup Cans–derived printed attire was in vogue in Manhattan high society.[22] Later that year, the company decided to give Warhol a $2000 ($19349 in 2022) commission for a Campbell's tomato soup can painting as a gift for Oliver G. Willits, its retiring chairman of the company's board of directors.[83] In 1964, Campbell's sent Warhol free cans as a sign of respect.[84] In January 1967, the company took legal action against Warhol for using a soup can label, without consent, for an Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, show announcement.[85] Also in 1967, Campbell's sent a letter to Random House, which was on the verge of publishing a Warhol book, regarding Campbell's legal perspective on his art, noting that Warhol's work would not be considered in conflict with their corporate intellectual property as long as he did not paint the logo on actual soup cans.[86] The letter also included a formal denial that Campbell's had ever had any influence on Warhol's artistic subjects.[87] That same year, the company produced the promotional Souper Dress (pictured right) that could be purchased for $1 ($8.78 in 2022) and 2 soup can labels.[43] In 1985, the company also commissioned Warhol to paint its dry soup mixes, which were new at the time. In 1993, the company bought a Warhol tomato soup can painting to hang in its corporate boardroom at its headquarters, and by 2012 the company had a licensing agreement with the Warhol estate to use Warhol's renditions on a variety of merchandise.[83] That year, the company celebrated the 50th anniversary of the series by partnering with Target Corporation to release four different Warhol-inspired, limited-edition designs of condensed tomato soup cans (pictured left) in its United States stores.[88]

Although Campbell's never pursued litigation against Warhol for his art, United States Supreme Court justices have stated that it is likely Warhol would have prevailed. E.g., in a majority opinion, Stephen Breyer noted in a computer-code case that "An 'artistic painting' might, for example, fall within the scope of fair use even though it precisely replicates a copyrighted 'advertising logo to make a comment about consumerism'". Regarding another Campbells Soup Company case (Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, which relies on [Luther] Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc.), Neil Gorsuch stated, "Campbell's Soup seems to me an easy case because the purpose of the use for Andy Warhol was not to sell tomato soup in the supermarket...It was to induce a reaction from a viewer in a museum or in other settings."[89]

Inspiration

Campbell's Soup Cans is considered Warhol's signature work.[90] For about a year, he made paintings from photographs, by his one-time love interest Edward Wallowitch, taken of soup cans in every condition and from every angle. During this time, he mixed his media (oil- and water-based paints) and cut stencils to help pursue realism.[91] Wallowitch's photographs served as the models for the tracing and copying that resulted in many of his 1961 and 1962 Campbell's Soup cans and dollar bill paintings and drawings.[92] In total, Warhol painted about 50 Campbell's Soup canvases from November 1961 to 1962. The Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné (edited by Georg Frei and Neil Printz) lists the 32-canvas main set, 3 large grid-style paintings (1 of 200 cans and 2 of 100 cans), and about a dozen-and-a-half still lifes.[93] Although Warhol had been trained in art school to paint still-life fruit bowls on a table, he longed to paint his favorite variety of Campbell's Soup (Tomato), remembered from the pantry of his childhood home. Warhol is quoted as saying "Many an afternoon at lunchtime Mom would open a can of Campbell's for me, because that's all we could afford, I love it to this day."[48]

Several anecdotal stories supposedly explain why Warhol chose Campbell's Soup cans as the focal point of his pop art. One reason is that he needed a new subject after he abandoned comic strips, a move taken in part due to his respect for the refined work of Roy Lichtenstein. According to Ted Carey—one of Warhol's commercial art assistants in the late 1950s—it was Muriel Latow who suggested the idea for both the soup cans and Warhol's early U.S. dollar paintings.[46] Although Gopnik notes that a variety of incompatible versions of events are told, he presents a version crafted from Latow's recollections, saying that Latow and Carey were visiting Warhol to console him in his predicament of being upstaged in comics. Warhol begged them for ideas and even paid Latow for making her thoughts available.[94] Although Tony Scherman and David Dalton tell a similar origin story, they note that John Mann (Carey's boyfriend)[95] had a different version, where Latow influenced Warhol[96] by asking about what Warhol disliked, which turned out to be grocery shopping, which in turn made him imagine getting Campbell's Soup cans from A&P.[96] Another account of Latow's influence on Warhol holds that she asked him what he loved most, and because he replied "money" she suggested that he paint U.S. dollar bills.[97] Latow was then an aspiring interior decorator, and owner of the Latow Art Gallery in the East 60s in Manhattan. She also told Warhol that he should paint "Something you see every day and something that everybody would recognize. Something like a can of Campbell's Soup." Carey said that Warhol responded by exclaiming: "Oh that sounds fabulous." A $50 ($489.64 in 2022) check dated November 23, 1961, in the archive of the Andy Warhol Museum, confirms the story that she charged him for giving him ideas.[98][99]

By one account, according to Carey, Warhol went to a supermarket the following day and bought a case of "all the soups", which Carey said he saw when he stopped by Warhol's apartment the next day. When the art critic G. R. Swenson asked Warhol in 1963 why he painted soup cans, the artist replied, "I used to drink it, I used to have the same lunch every day, for twenty years."[46][100] Another account holds that Warhol instructed his mother to buy a can of each of the 32 varieties of Campbell's Soup from the local A&P. He began with a series of drawings and then made color slides of each, to be projected onto a screen. He tinkered with dimensions and how best to combine the varieties. However, rather than combine them, as was common with supermarket food imagery of the time, he decided to create, with as much realism as he could, individual portraits against a white background.[48]

The soup is said to have reminded Warhol of his mother, Julia, who served it to him regularly while raising him during the Great Depression, as Czech immigrants in a Pennsylvania coal mine town.[101] At times, the family could not even afford to splurge on Campbell's Soup and ate soup made from ketchup.[102][103] It is regarded as doubtful that the Warhols had Campbell's Soup often, since it was marketed as an upscale item, and Julia was a soupmaker who could cook from scratch.[94] It wasn't until the late 1950s that canned soup was targeted toward the working class.[104]

In an interview for London's The Face in 1985, David Yarritu asked Warhol about flowers that Warhol's mother made from tin cans. In his response, Warhol talked about them as one of the reasons behind his first tin can paintings:

- David Yarritu: I heard that your mother used to make these little tin flowers and sell them to help support you in the early days.

- Andy Warhol: Oh God, yes, it's true, the tin flowers were made out of those fruit cans, that's the reason why I did my first tin-can paintings ... You take a tin-can, the bigger the tin-can the better, like the family size ones that peach halves come in, and I think you cut them with scissors. It's very easy and you just make flowers out of them. My mother always had lots of cans around, including the soup cans.[46]

Several stories mention that Warhol's choice of soup cans reflected his own avid devotion to Campbell's soup as a consumer. Robert Indiana once said: "I knew Andy very well. The reason he painted soup cans is that he liked soup."[105] He was thought to have focused on them because they composed a daily dietary staple.[106] Others observed that Warhol merely painted things he held close to his heart. He enjoyed eating Campbell's soup, had a taste for Coca-Cola, loved money, and admired movie stars. Thus, they all became subjects of his work. Yet another account says that his daily lunches in his studio consisted of Campbell's Soup and Coca-Cola, and thus his inspiration came from seeing the empty cans and bottles accumulate on his desk.[107]

Warhol did not choose the cans because of any business relationship with the Campbell Soup Company. Even though the company at the time sold four out of every five cans of prepared soup in the United States, Warhol preferred that the company not be involved, "because the whole point would be lost with any kind of commercial tie-in."[108] However, by 1965, the company knew him well enough that he was able to coax actual can labels from them to use as invitations for an exhibit.[109] They even commissioned a canvas.[110]

In 1961, Warhol painted a single "Campbell's Soup Can" on a 20-by-15-inch (51 cm × 38 cm) canvas and gave it to his brother Paul to celebrate the birth of Paul's son Marty. Each of Paul's children was able to exhibit the painting at school. Eventually, the family decided to auction off the work, on November 13, 2002, at Christie's in New York. This work is regarded as one of the inspirations for the later, well-known set.[111]

Artist colleagues

Willem de Kooning, who was among the artworld's elite by the 1960s, was among the artists who used the word soup metaphorically in reference to abstract expressionism, saying "Everything is already in art, Like a big bowl of soup. Everything is in there already...", while other New York artists used the word slangily as a way to discuss their art.[112]

According to Gopnik, there is scholarly opinion that Warhol's repetition of nearly identical Campbell's Soup Cans could be linked to Yves Klein's identical blue monochrome paintings. Gopnik notes that Klein had invited Warhol to his early 1962 wedding to Rotraut Klein-Moquay, and Warhol's work had incorporated International Klein Blue.[113]

In May 1961, Warhol purchased 6 miniature versions of Frank Stella's Benjamin Moore painting series. In this series, Stella represented the entire Benjamin Moore product line with a painting for each color. Scherman and Dalton feel this could have partly served as an inspiration for the complete set of Campbell's Soup cans.[114]

Interpretation

Warhol had a positive view of ordinary culture and felt that the abstract expressionists had taken great pains to ignore the splendor of modernity.[8] The Campbell's Soup Can series, along with his other series, provided him with a chance to express his positive view of modern culture. However, his deadpan manner endeavored to be devoid of emotional and social commentary.[8][115] The work was intended to be without personality or individual expression.[116][117] Warhol's view is encapsulated[41] in the Time magazine description of the 'Slice of Cake School', that "... a group of painters have come to the common conclusion that the most banal and even vulgar trappings of modern civilization can, when transposed to canvas, become Art."[37]

Warhol's pop-art work differed from serial works by artists such as Monet, who used series to represent discriminating perception and show that a painter could recreate shifts in time, light, season, and weather with hand and eye. Warhol is now understood to represent the modern era of commercialization and indiscriminate "sameness". When Warhol eventually showed variation, it was not "realistic". His later variations in color were almost a mockery of discriminating perception. His adoption of the pseudo-industrial silkscreen process spoke against the use of a series to demonstrate subtlety. Warhol sought to reject invention and nuance by creating the appearance that his work had been printed,[116] and he systematically recreated imperfections.[97] His series work helped him escape Lichtenstein's lengthening shadow.[118] Although his soup cans were not as shocking and vulgar as some of his other early pop art, they still offended the art world's sensibilities that had developed so as to partake in the artistic expression of intimate emotions.[116]

Contrasting against Caravaggio's sensual baskets of fruit, Chardin's plush peaches, or Cézanne's vibrant arrangements of apples, the mundane Campbell's Soup Cans gave the art world a chill. Furthermore, the idea of isolating eminently recognizable pop culture items was ridiculous enough to the art world that both the merits and ethics of the work were perfectly reasonably debatable topics, even for those who had not seen the piece.[119] Warhol's pop art can be seen in relation to Minimal art, in the sense that it attempts to portray objects in their most simple, immediately recognizable form. Pop art eliminates overtones and undertones that would otherwise be associated with representations.[120]

Warhol clearly changed the concept of art appreciation. Instead of harmonious three-dimensional arrangements of objects, he chose mechanical derivatives of commercial illustration, with an emphasis on the packaging.[108] His variations of multiple soup cans, for example, made the process of repetition an appreciated technique: "If you take a Campbell's Soup can and repeat it fifty times, you are not interested in the retinal image. According to Marcel Duchamp, what interests you is the concept that wants to put fifty Campbell's Soup cans on a canvas."[121] The regimented, multiple-can depictions almost become an abstraction whose details are less important than the panorama.[122] In a sense, the representation was more important than that which was represented.[120] Warhol's interest in machinelike creation, during his early pop-art days, was misunderstood by those in the art world, whose value system was threatened by mechanization.[123]

In Europe, audiences had a very different take on Warhol's work. Many perceived it as a subversive and Marxist satire on American capitalism.[108] If not subversive, it was at least considered a Marxist critique of pop culture.[124] Given Warhol's apolitical outlook in general, this is not likely the intended message. According to writer David Bourdon, Warhol's pop art may have been nothing more than an attempt to attract attention to his work.[108] Gopnik describes Warhol's presentation as objective and unblinking with no promotional intent.[125]

Variations

Campbell's Soup I and Campbell's Soup Cans II

_1962_Pencil_on_paper.jpg.webp)

In late 1961, Warhol began to learn the process of silkscreening from Floriano Vecchi,[16] who had run the Tiber Press since 1953. Though the process generally begins with a stencil drawing, it often evolves from a blown-up photograph that is then transferred, with glue, onto silk. In either case, one needs to produce a glue-based version of a positive two-dimensional image (positive means the open spaces that are left are where the paint will appear). Usually, the ink is rolled across the medium so that it passes through the silk and not the glue.[126] After the 1961 Christmas season ended, Vecchi, over the course of multiple visits, advised Warhol on how to refine his pigments and to use better squeegee techniques.[16] In 1962, Warhol's silk-screen printmaking techniques were also influenced by Manhattan graphic-art business owner Max Arthur Cohn.[127][128] It took Warhol until August 1962 to refine his technique of applying the paint with a rubber squeegee through the porous screen.[129] Campbell's Soup cans were among Warhol's first silkscreen productions; the first were U.S. dollar bills. The pieces were made from stencils; one for each color. Warhol did not begin to convert photographs to silkscreens until after the original series of Campbell's Soup cans had been produced.[58] Within 3 months, he was mass-producing silkscreens on various subjects, including Campbell's Soup cans.[130] In 1967, Warhol created Factory Additions, a company for printmaking and publishing.[131] According to Christopher Andreae of The Christian Science Monitor, Warhol produced two different 10-screenprint sets of Campbell's Soup cans in volumes of 250, one in 1968 and one in 1969.[132]

On April 7, 2016, seven Campbell's Soup Cans prints were stolen from the Springfield Art Museum. The FBI announced a $25,000 reward for information about the stolen art pieces from the "Campbell's Soup I" set.[133] They were a part of 1 of 250 sets of 10 screen prints that Warhol ordered in 1968, which had been donated to the museum in 1985 (by The Greenberg Gallery in St. Louis) and which were on display for the first time since 2006. Each of the screen prints had an estimated value of $30,000 ($36581 in 2022), according to Artnet author Blake Gopnik.[134] A National Public Radio source estimates that they generally sold for up to $45,000 ($54871 in 2022), but the tomato soup version could sell for $100,000 ($121936 in 2022). They were insured as a set and the insurance company paid $750,000 ($914517 in 2022), once the museum turned over the remaining three screen prints.[135]

When the Art Gallery of Ontario acquired a full Campbell's Soup I set in 2017, it became the first set in a public collection in Canada.[19] On November 8, 2022, climate-change protesters glued themselves to and vandalised another version of the "Campbell's Soup I" set that was on display at the National Gallery of Australia.[136][137] An edition of the second set, Campbell's Soup Cans II is part of the permanent collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago.[138][139][140][141][142][143][144][145][146][147] The Museum of Modern Art also has one of these sets.[148] In 2013, Hot Dog Bean soup from this set sold for $258,046 ($324180 in 2022) in Vienna.[61]

Colored soup cans

In 1965, Warhol revisited the Campbell's Soup cans theme while arbitrarily replacing the original red and white colors with a wider variety of hues. He produced a set of 20, 3 by 2 feet (91 cm × 61 cm) canvases, using either four or five colors in addition to black and, in some instances, white. This set is regarded as significant enough to tour as its own art exhibition. Ken Johnson, of The New York Times, noted that, in contrast to Warhol's usual "mechanical repetition", each painting was remarkable for its uniqueness.[149] 19 of the 20 were still in existence when 12 of them were presented in an exhibition in 2011.[150] At some point prior to 2004, the Museum of Modern Art had one of these.[151]

Unauthorized versions

In 1970, Warhol entered into a collaboration in which he facilitated exact duplications of some of his 1960s works by providing the photo negatives, precise color codes, screens, and film matrixes for European screenprint production. Warhol signed and numbered one edition of 250 before subsequent, unauthorized, unsigned versions were produced.[152][153] The unauthorized works were the result of a falling out between Warhol and some of his New York City studio employees who went to Brussels where they produced work stamped with "Sunday B Morning" and "Add Your Own Signature Here".[154] Some of the unauthorized productions bore the markings, "This is not by me, Andy Warhol".[153] Art galleries and dealers market "Sunday B Morning" reprints of several screenprint works, including those from the Campbell's Soup can sets.[155]

Other variations

Warhol followed the success of his original series with several related works incorporating the same theme of Campbell's Soup cans. By 1982 Warhol had painted over 100 renderings of Campbell's Soup cans.[156] These subsequent works, along with the original, are collectively referred to as the Campbell's Soup cans series and often simply as the Campbell's Soup cans. The subsequent Campbell's Soup can works were very diverse. Their heights ranged from 20 inches (510 mm) to 6 feet (1.8 m).[157] Occasionally, he chose to depict cans with torn labels, peeling labels, crushed bodies, or opened lids (see image right).[158][17]

According to the mobile audio tour at The Broad, Warhol produced 6 torn-label Campbell's Soup can paintings.[159] Two of these have resulted in record-setting sales. By 1970, Warhol established the record auction price for a painting by a living American artist with a $60,000 ($452134 in 2022) sale of Big Campbell's Soup Can with Torn Label (Vegetable Beef) (1962) in a sale at Parke-Bernet, the preeminent American auction house of the day (later acquired by Sotheby's).[9] The seller was a young Peter Brant, according to art dealer James Mayor.[160] By some accounts this was an arranged sale rather than an auction.[161] This record was broken a few months later by Warhol's rival for the art world's attention and approval, Lichtenstein, who sold a depiction of a giant brush stroke, Big Painting No. 6 (1965), for $75,000 ($565167 in 2022).[162]

%252C_1962.jpg.webp)

In May 2006, Warhol's Small Torn Campbell Soup Can (Pepper Pot) (1962) sold for $11,776,000 ($17.09 million in 2022) and set the current auction world record for a painting from the Campbell Soup Can series.[164][165] The painting was purchased for the collection of Eli Broad,[166] a man who once set the record for the largest credit card transaction when he purchased Lichtenstein's "I ... I'm Sorry" for $2.5 million with an American Express card.[167] The work is in the collection at The Broad.[168] The $11.8 million Warhol sale was part of the Christie's Sales of Impressionist, Modern, Post-War, and Contemporary art for the Spring Season of 2006. Total sales on the night it was auctioned were $143,187,200 ($207.86 million in 2022), which was the second highest auction night in history at the time.[164]

When Warhol (with Lichtenstein, Wesselmann, and Mary Inman) exhibited at The American Supermarket exhibition group show at the Bianchini Gallery in 1964, he presented both Campbell's Soup cans screen prints and autographed cans of Campbell's Soup, which he referred to as his "Duchamp number".[169] Warhol signed several cases of soup cans for the exhibition.[170] When Warhol was barraged by fans for soup can signatures, he or his assistants would put Warhol's signature on cans.[171]

200 Campbell's Soup Cans (1962, acrylic on canvas, 72 by 100 inches (182.9 cm × 254.0 cm)), in the private collection of John and Kimiko Powers, is the largest single canvas of the Campbell's Soup can paintings. It is composed of ten rows and twenty columns of numerous flavors of soups. Experts point to it as one of the most significant works of pop art, both as a pop representation and in conjunction with immediate predecessors such as Jasper Johns and the successor movements of Minimal and Conceptual art.[172] It was created as Warhol was developing skills to replace painting and drawing by hand, and he produced the repetitive series with stamps and stencils.[173] Its medium was synthetic polymer paint and silkscreen ink on canvas, according to one source.[174] The move to stamps and stencils reduced the flaws, and the subsequent move to silkscreen resulted in a process whose only variations were due to inconsistent mechanics: "leftover ink caking on the bottom of the screens, irregular seepage through the screens, or screens placed imprecisely and inconsistently on the canvas."[23] The earliest soup can painting seems to be Campbell's Soup Can (Tomato Rice), a 1961 ink, tempera, crayon, and oil canvas.[175]

In many of the works, including the original series, Warhol drastically simplified the gold medallion that appears on Campbell's Soup cans by replacing the paired allegorical figures with a flat yellow disk.[108] In most variations, the only hint of three-dimensionality came from the shading on the tin lid. Otherwise the image was flat. The works with torn labels are perceived as metaphors of life in the sense that even packaged food must meet its end. They are often described as expressionistic.[176]

The great variety of work produced using a semi-mechanized process with many collaborators, Warhol's popularity, the value of his works, and the diversity of works across various genre and media have created a need for the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board to certify the authenticity of works by Warhol.[177]

The Andy Warhol Museum of Modern Art had one of its Campbell's Soup Cans paintings stolen. It was estimated to have been worth €35,000 (€37636 in 2021). The theft occurred in March 2015, but it was not made public until August 2015.[178] In March 2021 in Manhattan, a Campbell's Soup Cans lithograph worth tens of thousands of dollars was stolen from art curator Gil Traub. Although the thief was identified on security video, the artwork was not recovered.[179]

Conclusion

Warhol's production of Campbell's Soup can works underwent three distinct phases. The first took place in 1962, during which he created realistic images, and produced numerous pencil drawings of the subject.[118] In 1965, his second phase involved multi-color soup cans.[149] In the late 1970s, he again returned to the soup cans while inverting and reversing the images.[175] The best-remembered Warhol Campbell's Soup can works are from the first phase. Warhol is further regarded for his iconic serial celebrity silkscreens of such people as Elvis Presley, Marilyn Monroe, and Liz Taylor, which were produced during his 1962–1964 silkscreening phase. His most commonly repeated painting subjects are Taylor, Monroe, Presley, Jackie Kennedy, and other celebrities.[180]

Irving Blum made the original thirty-two canvases available to the public through an arrangement with the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, by placing them on permanent loan on February 20, 1987, which was two days before Warhol's death.[97][181] While at the National Gallery of Art, they were installed in a 4-row, 8-column grid.[182] The works were on loan to the National Gallery of Art when the Museum of Modern Art acquired them for approximately $15 million on October 9, 1996 ($27.99 million in 2022).[183] The Museum of Modern Art attributes the source of funds for this purchase to a wide variety of sources: "Partial gift of Irving Blum Additional funding provided by Nelson A. Rockefeller Bequest, gift of Mr. and Mrs. William A. M. Burden, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Fund, gift of Nina and Gordon Bunshaft, acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest, Philip Johnson Fund, Frances R. Keech Bequest, gift of Mrs. Bliss Parkinson, and Florence B. Wesley Bequest (all by exchange)."[184]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "The Collection". The Museum of Modern Art. 2007. Retrieved March 9, 2007.

- ↑ Frazier, p. 708.

- ↑ Sherman/Dalton, pp. 73–74

- 1 2 3 Bockris (1997), p. 148

- 1 2 3 4 Angell, p. 38.

- 1 2 Livingstone, p. 32.

- 1 2 Lippard, p. 158.

- 1 2 3 Stokstad, p. 1130.

- 1 2 Bourdon p. 307.

- 1 2 Livingstone, p. 31.

- ↑ Watson, p. 25.

- ↑ Watson, pp. 27–28.

- ↑ Watson, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Harrison and Wood, p. 730.

- 1 2 Bourdon, p. 109.

- 1 2 3 4 Watson, p. 79.

- 1 2 Scherman/Dalton, p. 89–90.

- ↑ Danto, pp. 33-4.

- 1 2 Hampton, Chris (November 23, 2017). "Andy Warhol's Campbell's Soup I collection donated to AGO". The Globe and Mail. ProQuest 2382993664. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ↑ "Andy Warhol, Campbell's Soup II, 1969". Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ↑ "Andy Warhol, Campbell's Soup I, 1968". Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- 1 2 Dean, Martin (March 13, 2018). "The Story of Andy Warhol's 'Campbell's Soup Cans'". Sotheby's. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- 1 2 Flatley, p. 101.

- ↑ Danto, p. 81.

- ↑ Danto, p. 52.

- ↑ Shore, p. 26

- ↑ Watson, pp. 74–75.

- ↑ Angell, p. 84.

- ↑ Angell, p. 86.

- ↑ Sylvester, p. 386.

- ↑ Bourdon, p. 102.

- ↑ Bourdon, pp. 102–103.

- ↑ Bourdon, p. 100.

- ↑ Bockris (1997), p. 145

- ↑ Reder, Hillary. "Serial & Singular: Andy Warhol's Campbell's Soup Cans". Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ↑ Scherman/Dalton, p. 87

- 1 2 "The Slice-of-Cake School". Time. Vol. 79, no. 19. May 11, 1962. p. 52. Retrieved December 25, 2013.

- ↑ Watson p. 79–80.

- ↑ Flatley, pp. 2-3.

- 1 2 3 Scherman/Dalton, p. 101.

- 1 2 Bourdon, p. 110.

- 1 2 Gopnik, pp. 249–250.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rozzo, Mark (December 2018). "How the Campbell's Soup Paintings Became Andy Warhol's Meal Ticket". Vanity Fair. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ↑ Angell, p. 101.

- ↑ Weinraub, Bernard (May 23, 2002). "A Warhol Retrospective Comes to Los Angeles With Fitting Hoopla". The New York Times. p. E.1. ProQuest 432078113. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Comenas, Gary. "Warholstars: The Origin of the Soup Cans". warholstars.org. Retrieved January 4, 2007.

- ↑ Scherman, Tony; Dalton, David (2009). Pop, The Genius of Andy Warhol. Harper Collins. pp. 118. ISBN 9780066212432.

- 1 2 3 Bockris (1997). p. 144

- ↑ Gopnik, p. 260.

- ↑ Bockris (1989), p. 120.

- 1 2 Gopnik, p. 259.

- ↑ Archer, p. 14.

- 1 2 Watson p. 80.

- ↑ Bourdon, p. 120.

- 1 2 Scherman/Dalton, p. 120.

- ↑ Bourdon, p. 87.

- ↑ Gopnik, p. 261.

- 1 2 Bourdon, p. 123.

- 1 2 3 4 Gopnik, p. 262

- 1 2 Watson pp. 80–81.

- 1 2 3 Calleja, Bradley (July 29, 2022). "Art Insights: Investing in Soup". Altan Insights. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ↑ Johnson, Ken (May 8, 2015). "Review: A '60s View of Warhol's Soup Cans, at MoMA". The New York Times. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ↑ Gopnik, p. 258.

- ↑ Gopnik, pp. 274–275.

- ↑ Gopnik, p. 263.

- ↑ Scherman/Dalton, p. 93.

- 1 2 3 Gopnik, pp. 275–276.

- ↑ Scherman/Dalton, p. 129

- ↑ Gopnik, pp. 263-264.

- 1 2 Gopnik, pp. 280&ndsash;281.

- ↑ Gopnik, p. 283.

- ↑ Flatley, p. 15.

- 1 2 Martha Esposito Shea; Mike Mathis (2002). Campbell Soup Company. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-1058-0.

- ↑ Campbell Soup Can design, Campbell Soup Company. Newton, N.J.: Historic Conservation & Interpretation, Inc. 1999. OCLC 24632139.

- ↑ Cox, J. (2008). Sold on Radio: Advertisers in the Golden Age of Broadcasting. McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-7864-5176-0. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ↑ Robert Heide; John Gilman (2006). New Jersey: Daytripping, Backroads, Eateries, Funky Adventures. St. Martin's Griffin. p. 129. ISBN 0-312-34156-3.

The Campbell's Soup Company was begun when Joseph Campbell, a fruit merchant, and Abram Anderson, an icebox manufacturer, ... Arthur Dorance and Joseph Campbell then formed a new company called the Joseph Campbell Preserve Company. ...

- ↑ "Campbell's Australia". Archived from the original on July 16, 2010. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- ↑ "Tradition In A Bowl". CBS Mornings. December 21, 2022. ProQuest 2760696382. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ↑ Valinsky, Jordan (July 27, 2021). "Campbell's soup cans get first redesign in 50 years". CNN. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ↑ Leiby, Richard (April 26, 1994). "Campbell's to update its 'icon' soup label: [Final Edition]". Austin American-Statesman. p. C6. ProQuest 256401567. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ↑ Lowry, p. 227–228

- ↑ Gopnik, p. 242.

- 1 2 3 Choi, Candice (September 2, 2012). "Campbell's soup cans channel Andy Warhol". Montgomery Advertiser. p. 2. ProQuest 1223688259. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ↑ Gopnik, p. 401.

- ↑ Gopnik, p. 555.

- ↑ Meyer, Richard (June 7, 2023). "The Supreme Court Is Wrong About Andy Warhol". The New York Times. ProQuest 2823780006. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ↑ Mulroney, p. 66.

- ↑ Wee, Darren (September 4, 2012). "The public image: Andy Warhol Campbell's Soup cans: Marketing deconstructed". Financial Times. p. 14. ProQuest 1037811528. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ↑ Liptak, Adam (October 13, 2022). "Supreme Court Weighs In on Prince, Warhol and Copyrights: [National Desk]". The New York Times. p. A.18. ProQuest 2724115026. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ↑ Ketner, p. 66

- ↑ Gopnik, p. 230.

- ↑ Sherman/Dalton, p. 27.

- ↑ Scherman/Dalton, p. 77.

- 1 2 Gopnik, p. 227.

- ↑ Gopnik, p. 189.

- 1 2 Sherman/Dalton, pp. 74–75

- 1 2 3 Marcade p. 28.

- ↑ Scherman/Dalton, p. 73.

- ↑ Shore, p. 27

- ↑ Harrison and Wood, p. 732. Republished from Swenson, G. R., "What is Pop Art? Interviews with Eight Painters (Part I)," ARTnews, New York, November 7, 1963, reprinted in John Russell and Suzi Gabik (eds.), Pop Art Redefined, London, 1969, pp. 116–119.

- ↑ Morrison, James (January 20, 2002). "Revealed: the secret of Warhol's obsession with Campbell's soup: [FOREIGN Edition]". The Independent. ProQuest 311998987. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ↑ Gopnik, p. 6.

- ↑ Gopnik, p. 7.

- ↑ Gopnik, p. 228

- ↑ Comenas, Gary (December 1, 2002). "Warholstars". New York Times. Retrieved December 17, 2006.

- ↑ Faerna, p. 20.

- ↑ Baal-Teshuva, p. 18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bourdon, p. 90.

- ↑ Warhol and Hackett p. 163.

- ↑ Bourdon, p. 213.

- ↑ Vincent, John (October 29, 2002). "Warhol's brother to sell Campbell's soup can painting for pounds 1m: [Foreign Edition]". The Independent. ProQuest 312147354. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- ↑ Knight, Christopher (July 14, 2011). "Who inspired Warhol's 'Campbell's Soup Cans'?: The answer may lie with the abstract expressionists, and Willem de Kooning". Chicago Tribune. ProQuest 876277344. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- ↑ Gopnik, pp. 215–216.

- ↑ Scherman/Dalton, p. 57.

- ↑ Random House Library of Painting and Sculpture Volume 4, p. 187.

- 1 2 3 Warin, Vol 32, p. 862.

- ↑ Vaughan, Vol 5., p. 82.

- 1 2 Bourdon, p. 96.

- ↑ Bourdon, p. 88.

- 1 2 Lucie-Smith, p. 10.

- ↑ Constable, Rosalind, "New York's Avant Garde and How it Got There," New York Herald Tribune, May 17, 1964, p. 10. cited in Bourdon, p. 88.

- ↑ Bourdon, pp. 92–96.

- ↑ Lippard, p. 10.

- ↑ Livingstone, p. 16.

- ↑ Gopnik, p. 301.

- ↑ Warhol and Hackett, p. 28.

- ↑ "A Guide to Andy Warhol Prints: The Birth of an Iconic Pop Artist". Invaluable. April 8, 2021. Retrieved September 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Max Arthur Cohn" Archived December 29, 2017, at the Wayback Machine at SAAM.

- ↑ Bockris (1997) p. 151.

- ↑ Shore, p. 31

- ↑ "2019: 50 Works for 50 Years". South Dakota State University. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ↑ Andreae, Christopher (December 2, 1996). "Andy Warhol Keeps Popping Up: [ALL 12/02/96 Edition]". The Christian Science Monitor. ProQuest 291235295. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ↑ "FBI Offers $25K Reward After Iconic Warhol Art Stolen". NBC News.

- ↑ Holman, Gregory J. (February 21, 2019). "A courtyard, a wood chip and a 'weird code': The night Springfield's Warhols were stolen". Springfield News-Leader. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- ↑ Spencer, Laura (June 3, 2016). "Thieves Who Stole Warhol Prints From Springfield Art Museum Were Likely 'Amateurs'". KCUR, NPR. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- ↑ Roberts, Georgia (November 8, 2022). "Protesters vandalise Andy Warhol's Campbell's Soup Cans at National Gallery of Australia". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved September 10, 2023.

- ↑ "Climate activists target Andy Warhol's Campbell's soup cans at National Gallery of Australia". The Guardian. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Australian Associated Press. November 8, 2022. Retrieved September 10, 2023.

- ↑ "MCA - Collection: Campbell's Soup Cans II". mcachicago.org. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ↑ "MCA - Collection: Campbell's Soup Cans II". mcachicago.org. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ↑ "MCA - Collection: Campbell's Soup Cans II". mcachicago.org. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ↑ "MCA - Collection: Campbell's Soup Cans II". mcachicago.org. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ↑ "MCA - Collection: Campbell's Soup Cans II". mcachicago.org. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ↑ "MCA - Collection: Campbell's Soup Cans II". mcachicago.org. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ↑ "MCA - Collection: Campbell's Soup Cans II". mcachicago.org. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ↑ "MCA - Collection: Campbell's Soup Cans II". mcachicago.org. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ↑ "MCA - Collection: Campbell's Soup Cans II". mcachicago.org. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ↑ "MCA - Collection: Campbell's Soup Cans II". mcachicago.org. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ↑ "Andy Warhol, Campbell's Soup II, 1969". Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- 1 2 Johnson, Ken (May 20, 2011). "Andy Warhol: 'Colored Campbell's Soup Cans': [Review]". The New York Times. p. C. 25. ProQuest 867703902. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- ↑ Heinrich, Will (May 31, 2011). "$71 Million Can't Be Wrong! 'Andy Warhol Colored Campbell's Soup Cans' at L&M Arts". Observer.com. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ↑ Shanes, pp. 156–157.

- ↑ Davis, Holly (May 30, 2019). "RMFA to exhibit "A Tribute to Sunday B. Morning and Andy Warhol"". TCA Regional News. ProQuest 2231708051. Retrieved September 24, 2023.

- 1 2 Hintz, Paddy (December 8, 2007). "Factory practices: [1 First With The News Edition]". The Courier-Mail. p. T03. ProQuest 353917799. Retrieved September 24, 2023.

- ↑ Warren, Matt (April 17, 2001). "Factory prints: [S2 AND INTERACTIVE SUPPLEMENT Edition]". The Scotsman. p. 8. ProQuest 326950189. Retrieved September 24, 2023.

- ↑ "What Is Sunday B. Morning And What Is The Connection To Andy Warhol Art". Ginaartonline. May 18, 2015. Retrieved September 24, 2023.

- ↑ "Soup maker out to dish up new Warhol: [FINAL Edition]". The Pantagraph. June 6, 1995. ProQuest 252158930. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ↑ Bourdon, p. 91.

- ↑ Danto, p. 37.

- ↑ "Small Torn Campbell's Soup Can (Pepper Pot)". The Broad. Retrieved October 22, 2023.

- ↑ "'We nearly threw them out': the photographs of Andy Warhol that sat in a cupboard for 50 years". The Guardian. September 5, 2022. ProQuest 2709714422. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ↑ Gopnik, p. 730.

- ↑ Hahn, Susan (November 19, 1970). "Record Prices for Art Auction at New York Auction". Lowell Sun. p. 29. Retrieved May 12, 2012.

- ↑ "Andy Warhol's Campbell's Soup Cans - For Sale on Artsy". Artsy. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

- 1 2 "Andy Warhol's Campbell Soup Sells For $11.7 Million". ArtDaily. May 11, 2006. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Andy Warhol's Iconic Campbell's Soup Can Painting Sells for $11.7 Million". Fox News. Associated Press. May 10, 2006. Archived from the original on November 14, 2007. Retrieved January 29, 2007.

- ↑ AFP. (May 11, 2006). Auction sets record for Warhol's soup series. ABC News (Australia). Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- ↑ "American Topics". International Herald Tribune. January 25, 1995. Archived from the original on December 9, 2006. Retrieved January 30, 2007.

- ↑ "Small Torn Campbell's Soup Can (Pepper Pot)". The Broad. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ↑ Shore, p. 44.

- ↑ Gopnik, p. 402.

- ↑ Gopnik, p. 464.

- ↑ Lucie-Smith, p. 16.

- ↑ Flatley, p. 21.

- ↑ Flatley, p. 16.

- 1 2 Bourdon p. 99.

- ↑ Bourdon, p. 92.

- ↑ "The Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board, Inc". Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. Archived from the original on January 17, 2008. Retrieved March 9, 2007.

- ↑ Neuendorf, Henri (August 20, 2015). "European Andy Warhol Museum Loses Two Iconic Works in Shady Loan Agreement". Artnet. Retrieved September 10, 2023.

- ↑ Holmes, Helen (May 5, 2021). "A Lithograph of Andy Warhol's Iconic Campbell's Soup Can Was Stolen in Manhattan". The New York Observer. ProQuest 2522240699. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ↑ Sylvester, p. 384.

- ↑ Archer, p. 185.

- ↑ Garrells, p. 159

- ↑ Vogel, Carol (October 10, 1996). "Modern Acquires 2 Icons Of Pop Art". The New York Times. ProQuest 430682961. Retrieved September 10, 2023.

- ↑ "Andy Warhol, Campbell's Soup Cans, 1962". Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

References

- Angell, Callie (2006). Andy Warhol Screen Tests: The Films of Andy Warhol Catalogue Raissonné. New York: Abrams Books in Association With The Whitney Museum of American Art. ISBN 0-8109-5539-3.

- Archer, Michael (1997). Art Since 1960. Thames and Hudson Ltd. ISBN 0-500-20298-2.

- Baal-Teshuva, Jacob, ed. (2004). Andy Warhol: 1928–1987. Prutestel. ISBN 3-7913-1277-4.

- Bockris, Victor (October 1989). The Life and Death of Andy Warhol. Bantam Books. ISBN 0-553-05708-1.

- Bockris, Victor (1997). Warhol: The Biography. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80795-5.

- Bourdon, David (1989). Warhol. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. Publishing. ISBN 0-8109-2634-2.

- Danto, Arthur C. (2009). Andy Warhol. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-13555-8.

- Faerna, Jose Maria, ed. (September 1997). Warhol. Henry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers. ISBN 0-8109-4655-6.

- Flatley, Jonathan (2017). Like Andy Warhol. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-50557-2.

- Frazier, Nancy (2000). The Penguin Concise Dictionary of Art History. Penguin Group. ISBN 0-670-10015-3.

- Garrels, Gary, ed. (1996) [1989]. The Work of Andy Warhol. Bay Press. ISBN 0-941920-11-9.

- Gopnik, Blake (2020). Warhol. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-229839-3.

- Harrison, Charles; Wood, Paul, eds. (1993). Art Theory 1900–1990: An Anthology of Changing Ideas. Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-16575-4.

- Ketner II, Joseph D. (2013). Andy Warhol. Phaidon Press Limited. ISBN 978-0-7148-6158-6.

- Lippard, Lucy R. (1985) [1970]. Pop Art. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-20052-1.

- Livingstone, Marco, ed. (1991). Pop Art: An International Perspective. London: The Royal Academy of Arts. ISBN 0-8478-1475-0.

- various authors (2005). Lowry, Glenn D. (ed.). Masterworks of Modern Art: from the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Scala Vision. ISBN 88-8117-298-4.

- Lucie-Smith, Edward (1995). Artoday. Phaidon. ISBN 0-7148-3888-8.

- Marcade, Bernard; De Vree, Freddy (1989). Andy Warhol. Galerie Isy Brachot.

- Mulroney, Lucy (2018). Andy Warhol, Publisher. The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-54284-3.

- Random House Library of Painting and Sculpture Volume 4, Dictionary of Artists and Art Terms. Random House. 1981. ISBN 0-394-52131-5.

- Scherman, Tony; Dalton, David (2009). Pop, The Genius of Andy Warhol. Harper Collins. ISBN 9780066212432.

- Shanes, Eric (2004). Warhol. Confidential Concepts. ISBN 1-85995-920-2.

- Shore, Robert (2020). Andy Warhol. Laurence King Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-78627-610-0.

- Stokstad, Marilyn (1995). Art History. Prentice Hall, Inc., and Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers. ISBN 0-8109-1960-5.

- Sylvester, David (1997). About Modern Art: Critical Essays 1948–1997. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0-8050-4441-8. (Citing "Factory to Warhouse", May 22, 1994, Independent on Sunday Review as primary source)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Vaughan, William, ed. (2000). The Encyclopedia of Artists. Vol. 5. Oxford University Press, Inc.

- Warin, Jean, ed. (2002) [1996]. The Dictionary of Art. Vol. 32. Macmillan Publishers Limited.

- Warhol, Andy & Hackett, Pat (1980). Popism: The Warhol Sixties. Harcourt Books. ISBN 0-15-672960-1.

- Watson, Steven (2003). Factory Made: Warhol and the Sixties. Pantheon Books.

_05.jpg.webp)

_01.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)