| Canarese Konkani | |

|---|---|

| कॅनराचॆं कोंकणी, Canarachem Konkani | |

| Native to | India |

| Region | South Canara and North Canara of Carnataca, and Kassergode area of Kerala. |

Indo-European

| |

| Devanagari (official),[note 1] Latin[note 2] Kannada,[note 2] Malayalam and Persian | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Karnataka Konkani Sahitya Academy,[note 3] Kerala Konkani Academy[note 4] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

Distribution of native Canarese Konkani speakers in India | |

Canarese Konkani are a set of dialects spoken by minority Konkani people of the Canara sub-region of Karnataka, and also in Kassergode of Kerala that was part of South Canara.[note 5][1] Kanarese script is the primary mode of writing used in Canarese Konkani, as recognised by the Konkani Academy.

Names

The Karnataka Saraswat dialects are referred to as Canara Konkani. The Kerala dialects are referred to as Travancore Konkani or Kerala Konkani. Certain dialects like the Canara Saraswat dialects of the Gaud Saraswats and Bhanaps are called आमचीगॆलॆं āmcigelẽ (lit. ours) and the dialect of the Cochin Gaud Saraswats is called कॊच्चिमांय koccimā̃y (lit. mother Cochin) by the members of those communities.

The word Canara is a Portuguese rendering of the word Kannada. The early Portuguese conquistadors referred to Konkani as lingoa Canarim as a reference to Canara.[2]

Geographic distribution

The dialect is mainly spoken as a minority language in the Indian States of Karnataka, and in some parts of Kerala. The speakers are concentrated in the districts of Uttara Kannada district, Udupi and Dakshina Kannada in Karnataka.

History

Influx of Konkani speakers into Canara happened in various immigration waves:

- Exodus between 1312 and 1327 when General Malik Kafur of the Delhi Sultans Alauddin Khalji and Muhammed bin Tughlaq destroyed Govepuri and the Kadambas

- Exodus subsequent to 1470 when the Bahamani kingdom captured Goa, and subsequently in 1492 by Sultan Yusuf Adil Shah of Bijapur

- Hindu exodus due to Christianization of Goa by Portuguese missionaries subsequent to Portuguese conquest of Goa in 1510[3]

- Exodus of Christians who wanted to keep following Hindu customs even after the establishment of the Goa Inquisition in 1560; or wanted to escape epidemics, wars and taxation taking place in Goa[3]

The people

According to the 1991 census of India, 40.1% Konkani speakers hail from the state of Karnataka. In Karnataka over 80% of them are from the coastal districts of North and South Canara, including Udupi. 3.6% of the Konkani speakers are from Kerala, and nearly half of them are from Ernakulam district.[4]

Based on local language influence, Konkani speaking people are classified into three main regions:

North Canara (Uttara Kannada district, Karnataka)

This is the region north of the Gangolli river, starts from the Kali river of Karwar. The North Canarese are called baḍgikār[note 6] (Northerners) or simply baḍgi in Konkani. North Canarese Konkani has more of Goan Konkani influence than Kannada influence compared to South Canarese Konkani. The major Konkani speaking communities include:[5][6]

- Bhandaris

- Chitrapur Saraswat

- Daivadnya Brahmin

- Gabit

- Gaud Saraswat

- Kharvis

- Konkani Maratha

- Ramakshatriya

- Vani

Karwar Konkani is different from Mangalorean or South Canara Konkani. It is similar to Goan Konkani but mixed with Marathi accented words. Although people of Karwar have their mother tongue as Konkani, a few are conversant in Marathi too.

South Canara (Udupi and Mangalore districts, Karnataka)

This is the region south of the Gangolli river. The South Canarese are called ṭenkikār [note 6](Southerner) tenkabagli or simply ṭenki in Konkani. Rajapur Saraswat, Kudalkar, Daivajna, Kumbhar, Gaud Saraswats and Chitrapur Saraswats are some of the Konkani speaking communities of this region. 15% of Dakshina Kannada speaks Konkani.[7] South Canara Saraswats, both Gaud Saraswat and Chitrapur Saraswat affectionately refer to their dialect as āmcigelẽ (Ours) This region has recently been bifurcated into Udupi and Dakshina Kannada districts.

Konkani speakers in South Canara are trilingual; they are conversant in Konkani, Kannada and Tulu. Some of the towns in South Canara have separate Konkani names. Udupi is called ūḍip and Mangalore is called kodiyāl in Konkani.

Travancore (Cochin and Ernakulam district, Kerala)

Konkani speakers are found predominantly in the Cochin and Ernakulam, Alappuzha, Pathanamthitta, Kollam districts of Kerala, the erstwhile kingdom of Travancore. Kudumbis, Gaud Saraswats, Vaishya Vani of Cochin, and Daivajna are the major communities. The Konkani dialect of the Gaud Saraswats is affectionately referred to as koccimā̃y by members of that community.

The Gaud Saraswats of Cochin were part of the group of sāṣṭikārs who migrated from Goa during the Inquisition hence their dialect is, but for usage of certain Malayalam words, similar to the dialect spoken by Gaud Saraswats of South Canara.[8]

Konkani speakers in this region are bilingual; they are conversant in Konkani as well as Malayalam.

Description

Konkani in Karnataka has been in contact with Kannada and Tulu, thus showing Dravidian influence on its syntax.[9]

The phonetics, sounds, nasalization, grammar, syntax and in turn vocabulary obviously differs from Goan Konkani.[9]

There was a small population of Konkani speakers in Canara even before the first exodus from Goa. This group was responsible for the Shravanabelagola inscription. There was a large scale migration of Konkani communities from Goa to the coastal districts of North Canara, South Canara and Udupi. This migration, caused by the persecution of the Bahamani and Portuguese rulers, took place between the twelfth and seventeenth centuries. Most of these migrants were merchants, craftsmen and artisans. These migrants were either Hindus, Muslims or Christians and their linguistic practices were influenced by this factor also. Each dialect is influenced by its geographical antecedents.

There are subtle differences in the way that Konkani is spoken in different regions: "In Karwar and Ankola, they emphasize the syllables, and in Kumta-Honavar, they use consonants in abundance. The Konkani spoken by Nawayatis of Bhatkal incorporates Persian and Arabic words."[10] People of South Kanara do not distinguish between some nouns of Kannada and Konkani origin, and have developed a very business practical language. They sometimes add Tulu words also. It is but natural that Konkani has many social variations also because it is spoken by many communities such as Daivajna, Serugar, Mestri, Sutar, Gabeet, Kharvi, Samgar, Nawayati, etc.

Continuous inter action between the Konkani speaking communities with Dravidian Languages over a period of time has resulted in influences at the levels of morphology, syntax, vocabulary and larger semantic units such as proverbs and idioms.[11] This phenomenon is illustrated by Nadkarni, Bernd Heine and Tanya Kuteva in their writings.

Many Kannada words such as duḍḍu (money), baḍḍi (stick) and bāgilu (door) have found permanent places in Canara Konkani. Konkani from Kerala has Malayalam words like sari/śeri (correct), etc.

Dialect Variation

| Phrase | North Canara | South Canara | Cochin |

|---|---|---|---|

| What happened? | kasal jālẽ | kasan jāllẽ | kasal jāllẽ |

| correct | samma | samma | sari/ śeri |

| We are coming | āmi yetāti | āmmi yettāti / yettāci | āmmi yettāci |

| Come here | hekkaḍe/henga yo | hāṅgā yo | hāṅgā yo |

From the above table we see that South Canara and Kerala Hindu dialects undergo doubling of consonants āppaytā (calls), dzāllẽ (done), kellẽ (did), vhaṇṇi (sister in law) whereas North Canara Hindu dialects use the un-doubled ones āpaytā, dzālẽ, kelẽ, vhaṇi' . The Gaud Saraswat and Kudumbi Kochi dialects uses ca and ja in place tsa and dza respectively.

Language structure

Konkani speakers in Karnataka, having interacted with Kannada speakers in North Canara, Kannada and Tulu speakers in South Canara and Malayalam speakers in Kerala, their dialects have been influenced by Kannada, Tulu and Malayalam. This has resulted in Dravidian influence on their syntax.[9] According to the linguists, Konkani in Karnataka has undergone a process of degenitivization, and is moving towards dativization on the pattern of Dravidian languages. Degenitivization means the loss or replacement of the genitives, and dativization means replacement of the genitive in the donor language (i.e. Konkani) by the dative case marker in the recipient language (i.e. Kannada).[9] E.g.:

- rāmācẽ/-lẽ/-gelẽ kellelẽ kām.

- rāmānẽ kellelẽ kām.

- In the Goan dialects, both statements are grammatically correct. In the Karnataka dialects, only the second statement is grammatically correct.

In Karnataka Konkani present continuous tense is strikingly observable, which is not so prominent in Goan Konkani.[12] Present indefinite of the auxiliary is fused with present participle of the primary verb, and the auxiliary is partially dropped.[12] This difference became more prominent in dialects spoken in Karnataka, which came in contact with Dravidian languages, whereas Goan Konkani still retains the original form.

- In Goan Konkani "I eat", as well as "I am eating", translates to hā̃v khātā.

- In Kanara Konkani, "I eat" translates to hā̃v khātā and "I am eating" translates to hā̃v khātoāsā or hā̃v khāter āsā

Script

Early Konkani literature in Goa, Karnataka and Kerala has been found in the Nāgarī Script. At present however, Devanagari has been promulgated as the official script.[note 7]

Literature

The earliest known Konkani epigraphy is claimed to be the rock inscription at Shravanabelagola, Karnataka. However, the claim is disputed since as per many linguists its language is indistinguishable from that of the Old Marathi literature from Yadava era (1200–1300 CE)- the language is nearly identical, the script is early Devanagari, so it only makes sense to call it Marathi and not Konkani. This has always been a heated debate between Marathi Speakers and Konkani Speakers. Another writing of antiquity is a रायसपत्र Rāyasapatra (writ) By Srimad Sumatindra Tirtha swamiji to his disciples.

- Goḍḍe Rāmāyaṇ

In Konkani, Ramayana narration is found in both verse and prose. The story has been told in full or part in folksongs of the Kudubis and ritualistic forms like goḍḍe rāmāyaṇ of Kochi, sītā suddi and sītā kalyāṇa of Northern Kerala/South Canara and the rāmāyaṇa raṇmāḷe of Cancon. Some other texts of Ramayana too are available in written form in Konkani. rāmāyaṇācyo kāṇiyo, ascribed to Krishnadas Shama is in 16th century prose. During 1930s Late Kamalammal wrote the raghurāmāyaṇa in vhōvi[note 8] style verse. There have also been an adapted version by late Narahari Vittal Prabhu of Gokarn and recently, the translation of rāmacaritramānasa by Kochi Ananta Bhat of Kochi.[5][13]

- Hortus Malabaricus

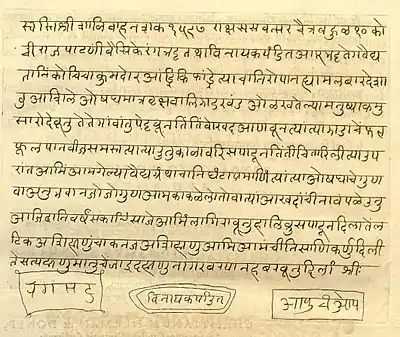

Hortus Malabaricus (meaning Garden of Malabar) is a comprehensive treatise that deals with the medicinal properties of the flora in the Indian state of Kerala. Originally written in Latin, it was compiled over a period of nearly 30 years and published from Amsterdam during 1678–1693. The book was conceived by Hendrik van Rheede, who was the Governor of the Dutch administration in Kochi (formerly Cochin) at the time.

Though the book was the result of the indomitable will power of Hendrik Van Rheede, all the basic work and the original compilation of plant properties was done by three Konkani Physicians of Kochi, namely Ranga Bhat, Vināyaka Pandit and Appu Bhat.[14] The three have themselves certified this in their joint certificate in Konkani, which appears as such at the start of the first volume of the book.

This book also contains the Konkani names of each plant, tree and creeper are also included throughout the book, in all 12 volumes, both in its descriptive parts and alongside their respective drawings. While the names are in Roman script in the descriptive part, the names alongside the diagrams are in original Nāgarī script itself, indicated as Bramanical characters.[14]

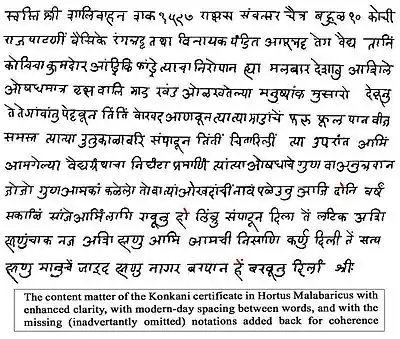

The 17th century certificate was etched in the manner and style of those times, which may appear unfamiliar now. Further to this, some writing notations (mostly anuswara) are seen missing in the print. Hence, to make it easily readable, the body matter is reproduced herein with enhanced clarity, modern-day spacing between words, and with the missing notations added back, for the sake of coherence and comprehension.

- Bhakti Movement

The Dvaita seer Madhavacharya converted Smartha Konkani Gaud Saraswats to Dvaitism. This Dvaita Gaud Saraswat community was instrumental in kīrtanasāhitya and haridāsasāhitya. Vasudev Prabhu was a very famous Konkani poet of the Bhakti Movement. He wrote many devotional songs in Konkani and also translated Kannada devotional poetry of Vyāsarāya, Naraharitirtha, Puranadaradāsa, Kanakadāsa. These Konkani songs were, later, sung by nārāyantirtha[15]

Contemporary Literature

Contemporary Konkani literature in Kerala made a rather late entry, as compared to its other concentrated states like Karnataka. However, according to historical annals, there can be established no exact evidence to relate exactly when Konkani language and literature began its predominating journey in Kerala. But a possible contact and interlinking between Goa with Kerala cannot be thrown to the wind, as collaborators in foreign trade. G Kamalammal is known to have contributed whole-heartedly to Konkani literature, in the domain of devotional writing. V. Krishna Vadyar, Bhakta R Kanhangad, S. T Chandrakala, S Kamat are some of the most renowned novelists in the Konkani dialect. Moving further ahead, V Venkates, K Narayan Naik, N Prakash and others have penned forceful short stories; P G Kamath has contributed to the sphere of essay writing.

Some of the most great and legendary poets in Konkani literature from Kerala, comprise: K Anant Bhat, N Purushottam Mallya, R Gopal Prabhu, P N S Sivanand Shenoy, N N Anandan, R S Bhaskar etc. Translations, folklore, criticism also have enriched the Konkani literature in Kerala. Stepping aside a little bit and directing the attention towards analytic and detailed study, Konkani literature in Kerala has been legendary and celebrated to have formulated dictionaries and encyclopaedias in considerable numbers.

Culture, media and arts

Konkani speakers have retained their language and culture in Karnataka and Kerala. Music, theatre and periodicals keep these communities in touch with the language.

Notable periodicals are pānchkadāyi, kodial khabar and sansakār bōdh.

Konkani theatre made a rather late entry into the Indian art scenario. Konkani theatre groups like rangakarmi kumbaḷe śrīnivās bhaṭ pratiṣṭhān, and raṅgayōgi rāmānand cūryā vēdike played an instrumental role in bringing Konkani theatre to the masses. raṅgakarmi Kumble Shrinivas Bhat, Late Hosad Babuti Naik, Late Late K. Balakrishna Pai (kuḷḷāppu), Sujeer Srinivas Rao (cinna kāsaragōḍ) and Vinod Gangolli are some noteworthy names. Ramananda Choorya was an eminent artist who encouraged people to develop Konkani theatre. He wrote the famous play dōni ghaḍi hāssunu kāḍi.

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Goa, Daman and Diu Act, 1987 section 1 subsection 2 clause (c) defines "Konkani language" as Konkani in Devanagari script, and section 3 subsection 1 promulgates Konkani to be the official language of the Union Territory.

- 1 2 The use of this script to write Konkani is not mandated by law in the states of Karnataka and Kerala. Nevertheless, its use is prevalent. Ref:- Where East looks West: success in English in Goa and on the Konkan Coast, By Dennis Kurzon p. 92

- ↑ estd. by Govt. of Karnataka in 1994

- ↑ estd. in 1980 by Govt. of Kerala

- ↑ The Constitution Act 1992 (71st Amendment)

- 1 2 Term used by Konkani speaking Gaud Saraswats and Chitrapur Sarasawts

- ↑ On 20 August 1992 Parliament of India by effecting the 78th amendment to the Constitution of India, Konkani in Devanagari script has been included in VIIIth Schedule of Constitution of India.

- ↑ A vhōvi is song made of a collection two or three liner stanzas typically sung during weddings by ladies

References

- ↑ "Issues of Linguistic Minorities, Language Use in Administration and National Integration" (Press release). Central Institute of Indian Languages. 19 October 2004.

- ↑ Mohan Lal (2001). The Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature (Volume Five (Sasay To Zorgot), Volume 5. New Delhi: Kendra Sahitya Academy. p. 4182. ISBN 81-260-1221-8.

- 1 2 Prabhu, Alan Machado (1999). Sarasvati's Children: A History of the Mangalorean Christians. I.J.A. Publications. ISBN 978-81-86778-25-8.

- ↑ Cardona, George; Dhanesh Jain (2007). "20:Konkani". The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge language family series. Rocky V. Miranda (illustrated ed.). Routledge. p. 1088. ISBN 978-0-415-77294-5.

- 1 2 Sardessaya, Manoharraya (2000). A History of Konkani literature: from 1500 to 1992. New Delhi: Kendra Sahitya Akademi. pp. 7, 9, 298. ISBN 978-81-7201-664-7.

- ↑ Chithra Salam (14 October 2009). "Uttara Kannada Jilla Parishada". Konkani Census. Open Publishing. Archived from the original on 13 March 2011. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- ↑ "District Census Handbook, Dakshina Kannada District" (Press release). Govt. of Karnataka. 2001.

- ↑ Kerala District Gazetteer. Thiruvananthapuram: Govt. Of Kerala. 1965. pp. 32–57.

- 1 2 3 4 Bhaskararao, Peri; Karumuri V. Subbarao (2004). "Non-nominative subjects in Dakkhani and Konkani". Non-nominative subjects. Grammar, Comparative and general. Vol. 1 (illustrated ed.). John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 332. ISBN 978-90-272-2970-0.

- ↑ D'Souza, V.S. (1955). The Navayats of Kanara- study in Cultural Contacts. Dharwad: Kannada Research Institute. pp. 12–20.

- ↑ V.Nithyanantha Bhat, Ela Suneethabai (2004). The Konkani Language: Historical and Linguistic Perspectives. Kochi: Sukriteendra, Oriental Research Institute. pp. 5–27.

- 1 2 Janardhan, Pandarinath Bhuvanendra (1991). A Higher Konkani grammar. P.B. Janardhan. p. 317.

- ↑ Custom Report. Mangalore: Konkani Language and Cultural Foundation. 2007. pp. 2, 3.

- 1 2 Manilal, K.S. (2003). Hortus Malabaricus – Vol. I. Thiruvananthapuram: Dept. of publications, University of Kerala. pp. 5–23. ISBN 81-86397-57-4.

- ↑ Prabhu, Vasudev (1904). padāñcẽ pustaka. Mangalore: Mangalore Trading Association's Sharada Press. pp. 4–23.