| Cape honey bee | |

|---|---|

| |

| A Cape honey bee on a Oxalis pes-caprae flower | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Apidae |

| Genus: | Apis |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | A. m. capensis |

| Trinomial name | |

| Apis mellifera capensis Eschscholtz, 1822 | |

| |

| The natural ranges of the

Cape honey bee,

contact zone where the two subspecies overlap and hybridize | |

The Cape honey bee or Cape bee (Apis mellifera capensis) is a southern South African subspecies of the western honey bee. They play a major role in South African agriculture and the economy of the Western Cape by pollinating crops and producing honey in the Western Cape region of South Africa. The species is endemic to the Western Cape region of South Africa on the coastal side of the Cape Fold mountain range.

The Cape honey bee is unique among honey bee subspecies because workers can lay diploid, female eggs, by means of thelytoky,[1] while workers of other subspecies (and, in fact, unmated females of virtually all other eusocial insects) can only lay haploid, male eggs. Not all workers are capable of thelytoky – only those expressing the thelytoky phenotype, which is controlled by a recessive allele at a single locus (workers must be homozygous at this locus to be able to reproduce by thelytoky).[2]

The bee tends to be darker in colour than the African honey bee (A.m. scutellata) with an almost entirely black abdomen, this differentiates it from African honey bees which have a yellow band on the upper abdomen. Other differences that might allow for differentiation of the subspecies from African honey bees are their propensity to lay multiple eggs in a single cell and the raised capping on their brood cells.[3]

Interaction with African bees

In 1990 beekeepers transported Cape honey bees into northern South Africa, where they do not occur naturally. This has created a problem for the region's African honey bee populations.[4] Reproducing diploid females without fertilization bypasses the eusocial insect hierarchy; an individual more related to her own offspring than to the offspring of the queen will trade her inclusive fitness benefits for individual fitness benefit of producing her own young.[5]

This opens up the possibility of social parasitism: If a female worker expressing the thelytokous phenotype from a Cape honey bee colony can enter a colony of A.m. scutellata, she can potentially take over that African bee colony.[6] A behavioral consequence of the thelytoky phenotype is queen pheromonal mimicry, which means the parasitic workers can sneak their eggs in to be raised with those from the African bees.[7] Although their eggs are removed by other workers,[8] African honey bee workers are not efficient enough to remove every egg,[9] it has been suggested that is because they're similar to the honey bee queen's eggs.[10]

As a result, the parasitic A.m. capensis workers increase in number within a host colony, while numbers of the A.m. scutellata workers that perform foraging duties (A.m. capensis workers are greatly under-represented in the foraging force of an infested colony) dwindle, owing to competition in egg laying between A.m. capensis workers and the queen, and to the eventual death of the queen. This causes the death of the colony upon which the capensis females depended, so they will then seek out a new host colony.[11]

Thelytokous parthenogenesis and maintenance of heterozygosity

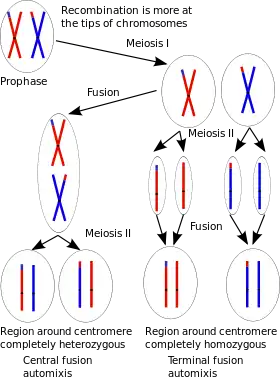

Parthenogenesis is a natural form of reproduction in which growth and development of embryos occur without fertilisation. Thelytoky is a particular form of parthenogenesis in which the development of a female individual occurs from an unfertilized egg. Automixis is a form of thelytoky, but there are different kinds of automixis. The kind of automixis relevant here is one in which two haploid products from the same meiosis combine to form a diploid zygote.

Cape honey bee workers expressing the thelytoky phenotype can produce progeny by automictic thelytoky with central fusion (see diagram).[12] Central fusion allows heterozygosity to be largely maintained. The oocytes that undergo automixis display a greater than 10-fold reduction in the rate of crossover recombination.[12] The low recombination rate in automictic oocytes favors maintenance of heterozygosity and the avoidance of inbreeding depression.

Impact on other animals

Although the Cape honey bee is regarded as being less aggressive than the African honey bee (A.m. scutellata) it can still be dangerous to people and other animals especially if the bees swarm and become defensive.[3][13] In 2021 a group of sixty African penguins were killed by Cape honey bees in a very rare incidence of the penguins coming into contact with a local hive.[13]

Conservation status

Although the species is officially classified as "not threatened" concerns exist that the subspecies might be declining in its natural range in the Western Cape. Threats to the subspecies include reduced access to flowering plants for forage, disease, parasites, and the use of pesticides and insecticides.[14]

In December 2008 American foulbrood disease spread to the Cape honey bee population in the Western Cape infecting and wiping out an estimated forty percent of the region's honey bee population by 2015.[15]

Over 300 hives were destroyed and more hives threatened with starvation in 2017 when large fires swept through the Knysna area of the Western Cape. Due to the impact of the fires on the bee's already threatened status resources were donated to set up additional hive stands and basil and borage after the fire to provide food to the bees.[16] Additional fires, at the same time, in the Thornhill area (near Port Elizabeth) destroyed a further 700 hives.

The use of pesticides by the agricultural sector is suspected of being responsible for at least one large incident of large scale hive death with an estimated 100 hives killed off on Constantia wine farms.[17]

South African non-profit Honeybee Heroes' Adopt-A-Hive initiative is a conservation project for the Cape honey bee.[18] Currently the organisation maintains over 700 honey bee hives dedicated to improving the population numbers of the Cape honey bee in the Western Cape.[19]

Gallery

A wild Cape honey bee hive in the hollow of a tree

A wild Cape honey bee hive in the hollow of a tree A bee swarm of Cape honey bees

A bee swarm of Cape honey bees Domestically kept Cape honey bees on a hive frame with honeycomb

Domestically kept Cape honey bees on a hive frame with honeycomb Honey comb

Honey comb

References

- ↑ Joanna Klein (9 June 2016). "Scientists Find Genes That Let These Bees Reproduce Without Males". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ↑ Lattorff, H.M. G., Mortiz, R.F.A. and Fuchs, S. 2005. A single locus determines thelytokous parthenogenesis of laying honeybee workers (Apis mellifera capensis). Heredity. 94: 533–537.

- 1 2 "Honeybees of South Africa | SABIO". www.sabio.org.za. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ↑ Hepburn, R. (2001). "The enigmatic Cape honey bee, Apis mellifera capensis". Bee World. Vol. 82. pp. 81–191.

- ↑ Hamilton, W.D. (1964). "Genetic evolution of social behavior, [part] I". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 7 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(64)90038-4. PMID 5875341.

- ↑ Hepburn, H.R.; Allsopp, M.H. "Reproductive conflict between honeybees – usurpation of Apis mellifera scutellata colonies by Apis mellifera capensis". South African Journal of Science. 90: 247–249.

- ↑ Neumann, Peter; Hepburn, Randall (2002). "Behavioural basis for social parasitism of Cape honeybees ( Apis mellifera capensis )". Apidologie. 33 (2): 165–192. doi:10.1051/apido:2002008. ISSN 0044-8435.

- ↑ Pirk, C. W. W. (2003-05-01). "Cape honeybees, Apis mellifera capensis, police worker-laid eggs despite the absence of relatedness benefits". Behavioral Ecology. 14 (3): 347–352. doi:10.1093/beheco/14.3.347.

- ↑ Moritz, Robin F. A.; Pirk, Christian W. W.; Hepburn, H. Randall; Neumann, Peter (2008). "Short-sighted evolution of virulence in parasitic honeybee workers (Apis mellifera capensis Esch.)". Naturwissenschaften. 95 (6): 507–513. doi:10.1007/s00114-008-0351-6. hdl:2263/9996. ISSN 0028-1042.

- ↑ Wossler, T.C. (2002). "Pheromone mimicry by Apis mellifera capensis social parasites leads to reproductive anarchy in host Apis mellifera scutellata colonies". Apidologie. 33 (2): 139–163. doi:10.1051/apido:2002006.

- ↑ Martin, S.J.; Beekman, M.; Wossler, T.C.; Ratnieks, F.L.W. (2002). "Parasitic cape honeybee workers, Apis mellifera capensis, evade policing". Nature. 415 (6868): 163–165. doi:10.1038/415163a. PMID 11805832. S2CID 4411884.

- 1 2 Baudry E, Kryger P, Allsopp M, Koeniger N, Vautrin D, Mougel F, Cornuet JM, Solignac M (2004). "Whole-genome scan in thelytokous-laying workers of the Cape honeybee (Apis mellifera capensis): central fusion, reduced recombination rates and centromere mapping using half-tetrad analysis". Genetics. 167 (1): 243–52. doi:10.1534/genetics.167.1.243. PMC 1470879. PMID 15166151.

- 1 2 Evans, Julia (2021-09-24). "OUR BURNING PLANET: Penguins killed by bees highlights a deeper conservation issue". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 2021-09-24.

- ↑ "Cape honeybee". SANBI. Retrieved 2021-09-24.

- ↑ Wossler, Theresa (31 July 2015). "The American disease that's wreaking havoc on South Africa's honeybee population". Quartz. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ↑ "R250k put aside for Knysna's destroyed beehives". News24. Retrieved 2017-06-22.

- ↑ Folb, Luke (25 November 2018). "Cape Town beekeepers uncover reasons for mass killing | Weekend Argus". Weekend Argus. Retrieved 2018-11-25.

- ↑ Selig, SarahBelle. "Western Cape residents warned about bee removal scammers". News24. Retrieved 2023-03-04.

- ↑ "The Art of Good Honey... and Helping Bees Thrive in South Africa!". Good Things Guy. 2021-04-29. Retrieved 2023-03-04.

External links

- Featured Creatures Website: Cape honey bee (Apis mellifera capensis) — on the UF / IFAS website.