Capitol View

Commissioner: Kimberly Martin | |

|---|---|

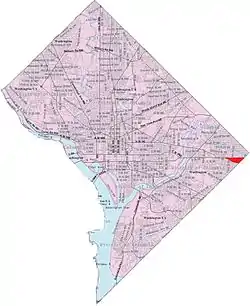

Capitol View within the District of Columbia | |

| Country | United States |

| District | Washington, D.C. |

| Ward | Ward 7 |

| Constructed | 1930s |

| Government | |

| • Councilmember | Vincent C. Gray |

| https://openanc.org/ancs/districts/7e07.html | |

Capitol View is a neighborhood located in southeast Washington, D.C., in the United States. It is bounded by East Capitol Street to the north, Central Avenue SE to the southwest and south, and Southern Avenue SE to the southeast. Still overwhelmingly African-American,[1] it is a thriving middle class neighborhood.

About the neighborhood

The area that became Capitol View was largely unsettled forest and farmland into the 1930s. By 1938, however, a large number of one- and two-story single-family detached houses and small apartment buildings had been constructed in the area. The neighborhood was almost exclusively populated by African Americans.[2] It was originally called DePriest Village.[3] As the neighborhood coalesced, it took the name Capitol View because the United States Capitol building could be seen (albeit distantly) on its western skyline.

Parts of the neighborhood became one of the city's most violent and drug-ridden areas in the 1980s and 1990s. The Capitol View neighborhood saw several large, poorly maintained public housing projects demolished in the 2010s. The government of the District of Columbia partnered with private real estate developers to construct the Capitol Gateway mixed-use development between 2000 and 2010.

Construction and Redevelopment

The character of the Capitol View neighborhood radically changed with the construction of large public housing complexes. The first of these, the East Capitol Dwellings, began construction in 1952 as a 394-unit public housing complex.[4] By the time the complex was completed in 1955, it had expanded to 577 units and straddled both sides of East Capitol Street between 58th and 60th Street. The new housing was racially desegregated, and was one of the first public housing complexes in the city to accept both whites and blacks from its inception.[5] The East Capitol Dwellings were the city's largest public housing development into the 2000s.[6] But the East Capitol Dwellings were shoddily constructed,[7] and problems with plumbing, HVAC, and poor maintenance plagued the 40-acre (0.16 km2) city-within-a-city until its demolition in 2003.[8]

The second major public housing complex was Capitol Plaza, which opened in 1971. This complex consisted of 92 three-story townhouses and a 228-unit, 12-story high-rise apartment building located at 5901 East Capitol Street SE.[9] A small strip mall, the eight-store Capitol View Mall, opened nearby in June 1976.[10] A second major high-rise development, Capitol Plaza II, opened shortly thereafter at 5929 East Capitol Street SE. This 300-unit, 12-story apartment building was open only to senior citizens, and suffered from extensive structural and design problems that caused the plumbing, HVAC, and electrical systems to fail.[11]

Realizing that it had over-concentrated the poor in a small area, the city moved to support the construction of affordable townhouses in the Capitol View neighborhood. In September 1990, the Capitol View Townhomes project opened next to the East Capitol Dwellings.[12] These townhouses were designed to accommodate mid-size and large families. Thirty-six of the units had three bedrooms, while 35 were four-bedroom and 19 were five-bedroom homes. Backed with city financing, the Capitol View Townhouses failed to sell. In 1997, the District of Columbia Housing Authority (DCHA), a nonprofit called Washington Innercity Self Help, and a company known as Innovative Design Solutions partnered to transform the townhouses into public housing. The city spent $5 million rehabilitating them, and in 2001 the three organizations supported residents of the properties in forming a cooperative, the Southern Homes and Gardens Cooperative, to own and manage the 90 townhomes. Under the city's agreement with Southern Homes and Gardens, the units must be managed as low-income public housing for 40 years. Units are either owned or rented by low-income people, and residents may enter into a rent-to-own agreement. At the end of the 40-year period, the townhomes may be sold by their owners (whether residents or the cooperative) at market rates.[13]

Capitol Gateway Redevelopment

Determined to improve its public housing stock, in 2000 DCHA applied for and won a $30.8 million grant (known as HOPE VI) from the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development. It demolished the East Capitol Dwellings, Capitol View Plaza, Capitol View Plaza II, and the Capitol View Townhomes,[14] and constructed Capitol Gateway—a 151-unit low-income senior citizen apartment building and 380 townhouses and single-family detached homes.[15] The townhouses and homes each cost $300,000 to construct.[16] As with Southern Homes and Gardens, DCHA sold the townhomes to low-income residents who wished to buy, entered into rent-to-own agreements with others, and leased the remaining homes to low-income families. In 2014, DCHA entered into an agreement with The Henson Companies to build the second phase of the Capitol Gateway. This $80 million project, to be constructed by The Henson Companies and real estate developer A&R Development, includes 312 low-income units in a mixed-use development. The ground floor of the property will include 20,000 square feet (1,900 m2) of retail space, and as part of the development package.

Grocery Store and Food Access

Wal-mart agreed to construct a 135,000-square-foot (12,500 m2) store adjacent to Capitol Gateway. Construction was set to begin on April 1, 2015.[15] However, amid closing 269 stores globally, Walmart announced it would not open its planned two stores- at Skyland Town Center and Capital Gateway. At the time many criticisms were leveled against Walmart by city leaders, as the planned stores were supposed to serve majority African-American populations underserved by grocery and retail stores and Walmart had already successfully built three stores in other parts of the city.[17] Many people believe that Walmart's decision not to build was due to the District's plans to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour and establishment of a paid-leave program. At the time Walmart issued a statement:

- "As part of a broad, strategic review of our existing portfolio and pipeline, we've concluded opening two additional stores in Washington, DC is not viable at this time. Our experience over the last three years operating our current stores in DC has given us a fuller view on building and operating stores in the District. This decision will not affect our three existing stores and we look forward to continue serving these customers in the future."[17]

In June, 2022 Mayor Muriel Bowser announced a forthcoming Giant supermarket development on site using eminent domain, saying Walmart refused to do what it stated it would do.[18]

Crime

The 1970s saw a significant rise in the sale and use of illegal narcotics in Capitol View, as well as gun-related violence.[14] As early as 1980, hundreds of dealers selling heroin, marijuana, methamphetamine, PCP lined the streets of Capitol View. The region's hilly nature allowed them to see police approaching, giving them a chance to escape across the border into Maryland, into local forested areas, or down alleys. Gunfire in the area was common, with at least three incidents each week.[19] By the late 1990s, violence was rampant in the neighborhood, and the Metropolitan Police Department called the East Capitol Dwellings one of the most violent public housing projects in the District of Columbia.[6]

In June 2009, the Capitol View neighborhood received nationwide attention after 55-year-old local woman Helen Foster-El was shot in the back and killed while attempting to rescue children at the East Capitol Dwellings caught in a crossfire between two groups of men arguing over a car.[6] Another five men were gunned down in broad daylight in the neighborhood a few weeks after her death. The District of Columbia later unsuccessfully sued gun manufacturers and distributors for millions of dollars in damages on behalf of Foster-el and others in the city killed with handguns.[16]

In the wake of the Foster-el murder, the Metropolitan Police Department changed its approach to violence in the neighborhood. Massive sweeps of drug dealers were made to break up the open-air, daylight drug markets, and drug dealing in the area declined significantly.[16] The Clay Terrace public housing project, long one of the city's most violent,[20] became a particular focus of police efforts. A no-questions-asked illegal gun depository program was implemented that recovered scores of weapons. Public housing residents with criminal records (especially drug or handgun crimes) were tracked and evicted. An anonymous text messaging site was created to allow residents to report drug dealing, gunfire, or other crimes. And an intensive city effort was made to fix street lights, clean and repair streets, and upgrade and maintain playgrounds and athletic facilities (particularly basketball courts). Crime at Clay Terrace dropped by 50 percent, and the police and city replicated its program each summer thereafter.[16]

Local residents, however, credit the rapid drop in crime throughout Capitol View to the demolition of the large public housing projects. (The drop in crime was part of a significant citywide improvement: Across the District of Columbia, homicides fell from 472 in 1990 to 88 in 2012.) Community organizations also sponsored literacy efforts to assist high school drop-outs in obtaining jobs, and the Marshall Heights Community Development Organization purchased the Capitol View Mall in an attempt to improve business and encourage job growth.[16]

Demographics

In 2012 Capitol View was a relatively poor, African-American neighborhood. Ninety-six percent of the neighborhood's residents were African-American. Almost 25 percent of the neighborhood's residents are under the age of 18, and half of these children belong to families whose incomes fall below the poverty line. Median household income was just $38,500 a year, compared to $61,835 a year for the District of Columbia as a whole. Unemployment is a serious issue in Capitol View. The official unemployment rate was 11 percent in 2012, although the real figure is widely considered to be higher. Unemployment in the city as a whole was 6.7 percent in the same period.[16]

Notable residents and landmarks

A number of landmarks lie on the border of the Capitol View neighborhood. The Capitol View neighborhood is dominated by East Capitol Street, a major vehicular and ceremonial thoroughfare. It is a vibrant commercial corridor, and acts as the focus of commercial life in the area.

Singer Marvin Gaye lived in the East Capitol Dwellings in the Capitol View neighborhood from about 1953 to 1962.[21][22]

Schools and Amenities

The Capitol View Neighborhood Library is located at 5001 Central Avenue SE, just outside the neighborhood's boundary on its west end.

Notable public landmarks include the Marion P. Shadd Elementary School, which was constructed in 1954.[23] It closed in 2007, and a public charter school, the Community College Preparatory Academy, opened in the structure.[24] Just behind the former Shadd Elementary School is the East Capitol Community Center, which contains an athletic field. It is maintained by the District of Columbia Department of Parks and Recreation.

W. Bruce Evans Junior High School is located adjacent to Capitol View's northern boundary at 5600 East Capitol Street NE. The school is named for W. Bruce Evans, the long-time principal at the Armstrong Manual Training School (a noted vocational-technical school for African-American youth that existed from the late 1800s to the 1950s).[25] Constructed in 1962,[26] it closed in 1996.[27] In 2007, the city renamed it the Evans Education Center, and it hosted occasional adult education classes. A public charter school, Maya Angelou High School, opened on the third floor in 2007. The charter school primarily enrolls students who are doing poorly academically, including those who have been held back a grade, are emotionally troubled, or have been incarcerated by the D.C. juvenile justice system.[28] Adjacent to the west side of the school is the Evans Recreation Center, an athletic field. (Evans Junior High School has two outdoor basketball courts and two outdoor tennis courts adjacent to the athletic field, but these are not maintained and are not open to the public.)

Transportation

D.C. Streetcar

Capitol View is one of several neighborhoods east of the river that would benefit from the extension of the D.C. streetcar. Approximately 37,000 people live within walking distance of the originally funded system but as of 2023 construction for this segment is delayed again. Friends of the D.C. Streetcar is a local group advocacy group.

Capital Bikeshare

The neighborhood has one Capital Bikeshare station at 53rd & D Street SE, just outside the southern border of the neighborhood, though more could be supported.[29]

Metro Access

To the west of the neighborhood boundary is the Benning Road metro station. Across the border in Maryland at the neighborhood's east end is the Capitol Heights Metro station, both stations serve the Blue and Silver lines of the Washington Metro subway system.

Pedestrian Access

The 2021 East Capitol Street Safety and Mobility Project includes plans to upgrade walking, cycling and transit conditions.

References

- ↑ "Memories of Capitol View" (PDF). Capitol View Civic Association History Committee. 2010 – via Office of Contracting and Procurement, Government of the District of Columbia.

- ↑ "Company Opposes Capitol View Buses". The Washington Post. May 13, 1938. p. 25.

- ↑ "About the Lincoln Heights/Richardson Dwellings Neighborhood". dcnewcommunities.org. 2021. Archived from the original on 2014-09-28. Retrieved 2021-02-14.

- ↑ "NCCP Blocks Highway Plan". The Washington Post. January 25, 1952. p. 16.

- ↑ Albrook, Robert C. (February 23, 1955). "July Deadline Named by NCHA Making Annual Report to Hill". The Washington Post. p. 25.

- 1 2 3 Thompson, Cheryl W.; Fountain, John W.; Chan, Sewell (June 23, 1999). "Arrest Made in Slaying of Bystander in SE D.C." The Washington Post. p. A1. Retrieved September 23, 2014.

- ↑ "East Capitol Dwellings Need $250,000 Repairs". The Washington Post. May 8, 1959. p. 16.

- ↑ Schwartzman, Paul (July 27, 2003). "The End of the Dwellings". The Washington Post. p. C11.

- ↑ Levy, Claudia (March 6, 1971). "Capitol View Plaza Dedicated". The Washington Post. p. B2.

- ↑ "Eight-Store Capitol View Mall Opens". The Washington Post. June 26, 1976. p. B4.

- ↑ Janofsky, Michael (November 26, 1998). "HUD Starts Inspection Plan Intended to Repair Housing". The New York Times. Retrieved September 23, 2014.

- ↑ "First Home". The Washington Post. September 15, 1990. p. D26.

- ↑ "Hope VI: Other DCHA Real Estate Projects - Southern Homes and Gardens". D.C. Housing Authority. March 9, 2009. Retrieved September 23, 2014.

- 1 2 Twohey, Megan (August 25, 2000). "Mixed-Opinion Development". Washington City Paper. Retrieved September 23, 2014.

- 1 2 Neibauer, Michael (September 23, 2014). "D.C.'s Next Gateway Project, Featuring Wal-Mart, to Break Ground in 2015". Washington Business Journal. Retrieved September 23, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Thompson, Krissah; Harris, Hamil R. (March 13, 2013). "'They Shoot and Don't Ask Questions'". The Washington Post. p. A1.

- 1 2 Sherwood, Tom (January 16, 2016). "DC Leaders Furious After Wal-Mart Drops Plans for 2 DC Stores Amid Closing of 269 Stores Worldwide". NBC4 Washington. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ↑ Wright, James Jr. (2022-06-16). "New Giant Supermarket Set for Ward 7". The Washington Informer. Retrieved 2022-06-30.

- ↑ Sargent, Edward D. (July 24, 1980). "Dealing Dope Among the Forgotten: East Capitol Projects Resist Drug Invasion". The Washington Post. p. DC1.

- ↑ Milloy, Courtland (November 2, 1980). "Business as Usual Where Street Seller Was Slain". The Washington Post. p. B1; Kessler, Ronald (October 31, 1983). "300 Stage March Against Drugs in NE Area". The Washington Post. p. B1; "4 Men Slain in D.C.". The Washington Post. August 2, 1989. p. B8; Lewis, Nancy (June 18, 1991). "Drug Dealer's Death Called One of Many in Reign of Terror". The Washington Post. p. B1; Gaines-Carter, Patrice; Wilgoren, Debbi (August 28, 1992). "On Clay Terrace, 3 More Shootings 'Ain't No Story'". The Washington Post. p. D1.

- ↑ Evelyn, Dickson & Ackerman 2008, pp. 290–291.

- ↑ Catlin, Roger (April 29, 2012). "Washington, D.C., Sites With Links to Marvin Gaye". The Washington Post. p. E8.

- ↑ "Wilson School Shutdown Is Approved: Pupils Transferred". The Washington Post. October 19, 1954. p. 17.

- ↑ Turque, Bill (April 26, 2012). "Four Charter Schools to Open in 2013". The Washington Post. p. T17.

- ↑ "Innovations in Schools". The Washington Post. March 13, 1907. p. 16.

- ↑ Jackson, Luther P. (October 29, 1961). "4000 District Children Need Help–But the Money Just Isn't There". The Washington Post. p. E2.

- ↑ Haggerty, Maryann (April 21, 1997). "D.C. Overstating Payoff From School Closings, Specialists Say". The Washington Post. p. B1.

- ↑ Pressley-Montes, Sue Ann (February 10, 2007). "Warm Welcome as Simon Elementary Reopens". The Washington Post. p. B2; Turque, Bill (December 23, 2011). "Successes and Hurdles". The Washington Post. p. B1.

- ↑ "Capital Bikeshare | Bike share in the Metro DC area". account.capitalbikeshare.com. Retrieved 2021-02-15.

Bibliography

- Evelyn, Douglas; Dickson, Paul; Ackerman, S.J. (2008). On This Spot: Pinpointing the Past in Washington, D.C. Sterling, Va.: Capital Books. ISBN 9781933102702.