| Caproni Ca.135 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Role | Medium bomber |

| Manufacturer | Caproni |

| Designer | Cesare Pallavicino |

| First flight | 1 April 1935 |

| Introduction | 1937 |

| Primary users | Regia Aeronautica Royal Hungarian Air Force Peruvian Aviation Corps |

| Produced | 1936–1941 |

| Number built | c. 140 |

The Caproni Ca.135 was an Italian medium bomber designed in Bergamo in Italy by Cesare Pallavicino. It flew for the first time in 1935, and entered service with the Peruvian Air Force in 1937, and with the Regia Aeronautica (Italian Royal Air Force) in January 1938.

A proposed variant with more powerful engines designated the Caproni Ca.325 was built only in mock-up form.

Origins

General Valle (Chief of Staff of the Regia Aeronautica) initiated the "R-plan" – a program designed to modernize Italy's air force, and to give it a strength of 3,000 aircraft by 1940. In late 1934 a competition was held for a bomber with the following specifications:

- Speed: 330 km/h (210 mph) at 4,500 m (14,800 ft) and 385 km/h (239 mph) at 5,000 m (16,000 ft).

- Rate of climb: 4,000 m (13,000 ft) in 12+1⁄2 minutes.

- Range: 1,000 km (620 mi) with a 1,200 kg (2,600 lb) bombload.

- Ceiling: 8,000 m (26,000 ft).

The ceiling and range specifications were not met, but the speed was exceeded by almost all the machines entered. At the end of the competition, the "winners" were the Ca.135 (with 204 aircraft ordered), the Fiat BR.20 (204), the Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 (96), the CANT Z.1007 (49), and the Piaggio P.32 (12).

This array of aircraft was proof of the anarchy, clientelism, and inefficiency that afflicted the Italian aviation industry. Worse was the continuous waste of resources by the Regia Aeronautica (Italian Royal Air Force). Orders were given for aircraft that were already obsolete. The winners of the competition were not always the best – the BR.20 was overlooked in favour of the SM.79, an aircraft which was not even entered in the competition.

Design

The Ca.135 was to be built at Caproni's main Taliedo factory in Milan, which is why the type had a designation in the main Caproni sequence, rather than in the Caproni-Bergamaschi Ca.300 series. However, the project was retained at Ponte San Pietro and the prototype, completed during 1934–35 (a long construction time for the period), was first flown on 1 April. The project chief was Cesare Pallavicino of CAB (Caproni Aereonautica Bergamasca).

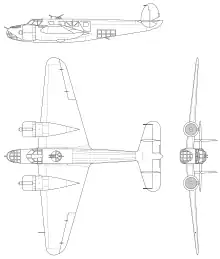

Although the new bomber was in the "century series" of Caproni aircraft, it resembled the Caproni Ca.310, with its rounded nose, two engines, low-slung fuselage and wings with a very long chord. Several versions were fitted with different engines and some had noticeable performance differences.

The prototype was powered by two 623 kW (835 hp) (at 4,000 m/13,000 ft) Isotta Fraschini Asso XI.RC radial engines initially fitted with two bladed wooden propellers. It had a length of 14.5 m (48 ft), a wingspan of 18.96 m (62.2 ft), and a wing surface of 61.5 m2 (662 sq ft). It weighed 5,606 kg (12,359 lb) empty and had a 2,875 kg (6,338 lb) useful load. Structurally, it was built of mixed materials, with a stressed-skin forward fuselage and a wood and fabric-covered steel-tube rear section; the wings being of metal and wood, using fabric and wood as a covering. The wings were more than 1⁄3 of the total length, and had two spars of wooden construction, covered with plywood and metal. The strength coefficient was 7.5. The tail surfaces were built of wood covered with metal and plywood. The fuel system, with two tanks in the inner wings, held a total of 2,200 L (581 US gal).

The Ca.135's fuselage shape was quite different from, for example, that of the Fiat BR.20. If the latter resembled the American B-25 Mitchell, the Ca.135, with its low fuselage more resembled the American B-26 Marauder. Its long nose accommodated the bomb-aimer (bombardier) and a front turret (similar to the Piaggio P.108 and later British bombers). The front part of the nose was detachable to allow a quick exit from the aircraft. It also had two doors in the cockpit roof, giving the pilots the chance to escape in an emergency. The right-hand seat could fold up to assist entry to the nose.

A single 12.7 mm (0.5 in) in a turret in mid-fuselage, was manned by the co-pilot. A seat for the flight engineer was later fitted. The wireless operator's station, in the aft fuselage, was fitted with the AR350/AR5 (the standard for Italian bombers), a radiogoniometer (P63N), an OMI AGR.90 photographic-planimetric machine or the similar AGR 61. The aircraft was also equipped with an APR 3 camera which although not fixed, was normally operated through a small window. The wireless operator also had a 12.7 mm (0.5 in) machine gun in the ventral position. All this equipment made him very busy; as a result, an extra man was often carried. The aircraft had very wide glazed surfaces in the nose, cockpit, and the central and aft fuselage; much more than in other Italian aircraft.

The aircraft was fitted with three machine guns: two 12.7 mm (0.5 in) calibre in the upper turret rsp. belly-stand and one 7.7 mm (0.303 in) calibre gun in the nose. All had 500 rounds, except the 7.7 mm (0.303 in) which had 350.

Bombload, like most Italian bombers, was less than impressive in terms of total weight, but was relatively flexible, depending on the role – from anti-ship to close air support:

- 2 × 800 kg (1,800 lb) bombs (the heaviest in the Regia Aeronautica), plus 2 × 50 kg (110 lb), and 2 × 31 kg (68 lb), for a total of 1,862 kg (4,105 lb)

- 2 × 500 kg (1,100 lb) + 4 × 100 kg (220 lb) + 2 × 31 kg (68 lb), total nominal 1,462 kg (3,223 lb)

- 4 × 250 kg (550 lb)

- 8 × 100 kg (220 lb) + 8 × 50 kg (110 lb) + 4 × 31 kg (68 lb), total 1,324 kg (2,919 lb)

- 16 × 50 kg (110 lb) + 8 × 31 kg (68 lb), total 1,048 kg (2,310 lb)

- 24 × 31 kg (68 lb), 20 kg (44 lb), 15 kg (33 lb), or 12 kg (26 lb).

- 120 × 1 or 2 kg (2.2 or 4.4 lb) bomblets

- 2 × torpedoes (never used, but hardpoints were fitted)

The aircraft had a better bomb capacity than most of its contemporaries (the SM.79 could carry: 2 × 500 kg/1,100 , 5 × 250 kg (550 lb), 12 × 100 or 50 kg (220 or 110 lb) bombs, or 700 × 1–2 kg (2.2–4.4 lb) bomblets).

Performance

The aircraft was underpowered, with a maximum speed of 363 km/h (226 mph) at 4,500 m (14,800 ft) and a high minimum speed of 130 km/h (81 mph), (there were no slats, and maybe not even flaps). Ceiling was only 6,000 m (20,000 ft) and the endurance, at 70% of throttle, was 1,600 km (990 mi). All-up weight was too high, with total of 8,725 kg (19,235 lb), not 7,375 kg (16,259 lb) as expected.

The total payload of 2,800 kg (6,200 lb) was shared between the crew (320+ kg/705+ lb), weapons (200 kg/440 lb), radios and other equipment (100 kg/220 lb), fuel (2,200 L/581 US gal), oil (1,500 kg/3,300 lb), oxygen and bombs. There was almost no chance of carrying a full load of fuel with the maximum bombload, (other Italian bombers were generally capable of a 3,300–3,600 kg/7,300–7,900 lb payload). The lack of power made take-offs when over-loaded, impossible. Indeed, even with a normal load, take-offs were problematic.

Take-off and landing distances were 418 and 430 m (1,371 and 1,411 ft). The range was good enough to assure 2,200 km (1,400 mi) with 550 kg (1,210 lb) and 1,200 km (750 mi) with 1,200 kg (2,600 lb).

The production version was fitted with two inline liquid-cooled Asso XI RC.40 engines, each giving 671 kW (900 hp) at 4,000 m (13,000 ft). Aerodynamic drag was reduced, with three-bladed metal propellers that were theoretically more efficient. These new engines gave the aircraft a maximum speed of 400 km/h (250 mph) at 4,000 m (13,000 ft). It could climb to 2,000 m (6,600 ft) in 5.5 minutes, 4,000 m (13,000 ft) in 12.1 minutes and 5,000 m (16,000 ft) in 16.9 minutes.

Despite this, the aircraft was still underpowered, so the 1939 Ca.135Mod, fitted with 746 kW (1,000 hp) Piaggio P.XI engines, was developed.

Operational service

The aircraft arrived late in respect to the others (like the BR.20), and with totally unsatisfactory technology. Despite this there was an order for 32 aircraft from the Regia Aeronautica on 19 June 1937. They started to enter service in January 1938, over a year after the BR and SM bombers.

Spanish Civil War

In 1938 seven aircraft were earmarked for the Aviazione Legionaria to serve in the Spanish Civil War. These Tipo Spagna ("Spanish Type") aircraft were refitted with Fiat A.80 R.C.41 engines, rated at 746 kW (1,000 hp).

Crews from 11 Wing were sent to Taliedo (just outside Milan), to take the first seven aircraft – designated Ca.135S – to Spain. One was damaged on take-off, the other six flew to Ciampino near Rome, where two suffered damage on landing. After repairs and some modifications, the seven aircraft were not ready to leave for Spain until late 1938. During the flight two were forced by icing to return to Italy and three crashed into the sea. Only two arrived at Palma de Mallorca, where they remained unused for six months.

Italy

Production of the aircraft was initially 32 aircraft, of which eight were Ca.135Ss, some were converted into the Ca.135Mod. The first Ca.135Bis were built in 1938. They were fitted with 746 kW (1,000 hp) Piaggio P.XI RC.40 engines, with Piaggio P.1001 three-blade metal propellers. Length was 17.7 m (58 ft), wingspan 18.8 m (62 ft), and wing surface 60 m2 (646 ft2). Armament was still only two 12.7 mm (0.5 in) guns and one 7.7 mm (0.303 in), but the nose was redesigned to be more aerodynamic. Another 32 aircraft were ordered and built between 1939 and June 1940.

They were not successful aircraft, being heavily criticized by the Italian pilots. Unable to be used operationally, they were sent to flying schools, and then exported to Hungary. The first batch of Ca.135s flown by 11 Wing were phased out by late 1938. 25 were still available at Jesi airfield, but only four were airworthy. The others were probably in maintenance for engine replacement. There were at least 15 Ca.135Ss and Ca.135Mods at the Malpensa flying school in 1940, the poor condition of these aircraft meant that they were scrapped in November 1941. With the scrapping of the first batch and the selling of the second, all 64 Ca.135s left the service of the Regia Aeronautica without performing a single operational mission.

Hungary

The Magyar Királyi Honvéd Légierő (MKHL; the Royal Hungarian Air Force) ordered Ca.135s which were delivered in 1940 and 1942 in two series of 36 rsp. 31 (originally 32, but one plane was lost on the delivery flight) planes. Also a licence production of aircraft and engines was considered.

The Hungarians operated a total of 67 Ca.135bis with some success against the Soviet Union on the Eastern Front in 1941 and 1942, once Hungary had committed its forces in that sector during World War II.

These aircraft constituted almost the entire Hungarian heavy bomber force. They were ordered after Hungarians returned 33 out of 36 Caproni Ca.310s acquired between May and September 1939. Because of an Italian credit for 300 million lire and the impossibility of acquiring modern German aircraft, the Hungarian Air Force acquired the new, more powerful, Ca.135bis. They were ordered in Dec 1939.[1] After that "deal" the first charge was delivered in May/June 1940, the second one in May 1942 (from a second order submitted in July 1941). Regia Aeronautica had rejected the Ca.135s on account of its technical shortcomings and the aircraft had been taken off production. But in Hungarian service this bomber proved quite satisfactory.[1]

When Hungary declared war on the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Hungarian Air Force was almost entirely equipped with Italian aircraft.[1] The bombers had their baptism of fire on 27 June 1941, the day Hungary declared war. That day, 1st Lt Istvan Szakonyi, in his Ca.135 from the 4/III Bomber Group, managed to destroy an important bridge with a 'trial drop' of two bombs.[2] The Ca.135s equipped the 3./III Group of 3rd Bomber Wing, based in Debrecen, a bomber unit of the Hungarian air formation commanded by Lt Col Béla Orosz, that had been tasked to provide air support to the Hungarian Rapid Corps, subordinated to the German 17th Army.[3]

On 11 August, six Capronis, commanded by 1st Lt Szakonyi, took off to bomb a 2 km (6,560 ft) bridge across the Bug River of the city of Nikolayev, on the Black sea. One Ca.135 had to turn back due to engine problems, but the other five, escorted by Hungarian Fiat CR.42s and MÁVAG Héja Is, continued eastwards. Szakonyi's Caproni was hit by AA fire and lost his port engine but the squadron commander remained in action. One of his pilots, Capt. Eszenyi, destroyed the bridge, and Szakonyi bombed the Nikolayev train station. On the way back the Capronis were intercepted by Soviet Polikarpov I-16 fighters. The escorting Hungarian fighters shot down five I-16s, while Szakonyi's crippled Ca.135 managed to destroy another three Polikarpovs. After the German 11th Army captured Nikolayev, on 16 August, the commander of Luftflotte 4, Col Gen Lohr, decorated the successful Hungarian crews at Sutyska.[4]

The Ca.135 on the Eastern Front had frequent malfunctions and its insufficient combat load-carrying capability set high demands on the mechanics maintaining it. A 50% operational readiness of the Capronis was to be seen as a great achievement.[1] The first Hungarian Flying formation on the Eastern Front was withdrawn in September 1941, for recuperation, re-equipment and rest. In June 1942, the Hungarians sent the 2nd Air Brigade to provide tactical support and reconnaissance sorties to the Hungarian 2nd Army, deployed on the Don. The only bombardment unit, the 4/1 Bomber squadron, was equipped with 17 Ca.135s.[5]

The 4° squadron operated these aircraft until late 1942, when the survivors, worn out, were used as training aircraft. The Hungarians did not love the Ca.135Bis, but it was all they had, so they had to make the most of it. One of the squadrons, the I/4, (originally equipped with eight aircraft), soon lost one on landing. It was replaced by another four aircraft. This squadron, up to October 1941, carried out 265 attacks, flew 1,040 sorties, and dropped around 1,450 tonnes (1,600 tons) of bombs, evidently helped by the short range (200–300 km/120–190 mi) that allowed them to use the aircraft's maximum bomb load. Two aircraft were shot down, another two were lost in accidents and 11 crewmen were killed. The daily average, over these four months, was over 8 missions flown and 13 tonnes (14 tons) of bombs dropped.

Peru

Design and production

Early in 1936, Caproni's representative in Lima, Peru, approached the Peruvian Navy and Aviation Ministry regarding the possible Peruvian purchase of Ca.135 aircraft. Peru had been considering the replacement of its unsatisfactory Caproni Ca.111 bombers since 1935, and the Italian Air Ministry approved of the foreign sale of the Ca.135. Consequently, Peru ordered six Ca.135s from Caproni in May 1936. Peruvian Aviation Corps Commander Ergasto Silva Guillen led a Peruvian delegation to Italy to evaluate the Ca.135 and to ensure that there was no repeat of what Peruvians recall as the "Ca.111 fiasco". Caproni test pilot Ettore Wengi made a demonstration flight for the Peruvians which left Silva unimpressed; he viewed the Ca.135 as underpowered and lacking in defensive armament and wrote a letter to the Caproni company insisting on modifications to the aircraft and threatening to cancel the Peruvian order if they were not made. Caproni company founder Gianni Caproni (1886–1957) personally promised that the changes would be made.[6]

The resulting version of the aircraft, the Ca.135 Tipo Peru ("Peruvian Type"), had more powerful engines—Isotta Fraschini Asso XI R.C.40 Spinto ("Driven") engines, uprated versions of the Isotta Fraschini R.C.40 Asso ("Ace") delivering 559 kilowatts (750 horsepower) at sea level and 671 kilowatts (900 horsepower) at 4,000 meters (13,123 ft) – and modified engine cowlings with additional openings to accommodate the additional air intakes of the new engines. The new engines gave the Ca.135 better performance that met the Peruvian requirements, and also allowed an increase in the aircraft's bomb load to 2,000 kilograms (4,409 pounds). Defensive armament was improved by the installation of a 12.7-millimeter (0.5-inch) machine gun in a semi-open dorsal turret equipped with a wind deflector shield to protect the gunner and another 12.7-millimeter machine gun in a retractable ventral turret.[7] Both turrets had a 360-degree field of fire, although the ventral turret produced excessive aerodynamic drag when extended and was recommended for use only in emergencies.[6]

All six Ca.135 Tipo Peru aircraft were completed in early July 1937. After test flights by Wengi and acceptance by the Peruvian delegation, they were disassembled and shipped to Callao, Peru. Personnel of the Caproni company's Peruvian subsidiary, Caproni Peruana S.A., promptly began their reassembly at Las Palmas. The first Ca.135 was reassembled within two weeks, and the first flights in Peru took place when the six bombers were turned over to the Peruvian Aviation Corps' new 2nd Heavy Bomber Squadron on 10 September 1937.[6]

Operational service

After their pilots had undergone two months of intensive training by Italian officers, five 2nd Heavy Bomber Squadron Ca.135s flew to their permanent base, the Lieutenant Commander Ruiz base, at Chiclayo, Peru, on 5 November 1937, while the sixth bomber remained at Las Palmas to train additional personnel.[7] Once at Chiclayo, the five Ca.135s became the 2nd Bombardment Group, joining the Ca.111 bombers of the 1st Bombardment Group as part of the 1st Aviation Squadron. In 1940 a reorganization resulted in the Ca.135s being assigned to the 13th, 14th, and 15th Escuadrillas alongside Ca.111 bombers, although later in the year the Ca.111s were reclassified as transport aircraft and reassigned to transport squadrons, at which point the 14th and 15th Ecuadrillas were disbanded and all Ca.135s were assigned to the 13th Escuadrilla.[6]

In service, the Ca.135 Tipo Peru soon came under criticism, with Peruvian pilots complaining that the bombers yawed to the right on take-off and had poor lateral stability; in addition, their engines proved unreliable in service, and the bombers suffered an excessive number of oil and hydraulic leaks. Caproni Peruana S.A. noted these problems and made plans to correct them in a version of the Ca.135 to be manufactured in Peru, although in the end no Ca.135s were built in Peru.[6]

As the result of a growing border crisis with Ecuador in 1941, the bomber squadrons of the Peruvian Aviation Corps were ordered into operational readiness, although engine problems kept them from having more than two aircraft out of each squadron's assigned five bombers airworthy at any given time. However, the Peruvian bombers were able to train at a bombing range north of Chiclayo. When the Ecuadorian–Peruvian War broke out on 5 July 1941, the Ca.135s remained behind at the Lieutenant Commander Ruiz base while other bombers moved to forward airfields, the greater range of the Ca.135s allowing them to avoid the need to move to forward air bases. However, Peruvian bombing missions were limited to tactical attacks on Ecuadorian troops in the front lines and facilities and forces supporting them directly, a type of attack to which Ca.135s were unsuited. Instead, the Ca.135s conducted unescorted reconnaissance flights over Ecuadorian territory and transport flights to the airfields at Piura and Talara, Peru. On 10 July 1941, during a transport flight, one of the Ca.135s was forced down by engine problems in an area inaccessible to ground vehicles about 50 kilometers (31 mi) from Piura; although it suffered only minor damage, its disassembly for transportation to a repair facility was infeasible, so it was stripped and abandoned.[6]

After the war ended on 31 July 1942, the five surviving Ca.135s remained at Chiclayo. They soon were removed from service, disassembled, and carted away on flatbed trucks driven by American military personnel from El Pato airbase. By October 1942, the last of the Peruvian Ca.135s had disappeared. Although they are rumored to have been burned in the desert or buried somewhere around the El Pato air base, their final fate is unrecorded.[7]

Modified aircraft

A single Ca.135 P.XI was modified by Caproni. It incorporated a dihedral tailplane and 1,044 kW (1,400 hp) Alfa Romeo 135 RC.32 Tornado radial engines, and given the designation Ca.135 bis/Alfa. The newer and more powerful engines pushed the maximum speed of the aircraft to more than 480 km/h (300 mph).

The final variant was also a one-off, known as the Ca.135 Raid. It was used to set records and win air races. It was built in 1937 to the order of the Brazilian pilot de Barros. It was powered by two 736 kW (987 hp) Isotta Fraschini Asso XI and provided with additional fuel capacity for a greatly extended range. While attempting a flight from Italy to Brazil in 1937, de Barros and the Ca.135 Raid disappeared over North Africa, in another disaster for the image of the aircraft.

Variants

- Ca.135 Tipo Spagna

- Seven aircraft fitted with 746 kW (1,000 hp) Fiat A.80 R.C.41 engines for service in Spain.

- Ca.135 P.XI

- Medium bomber version, powered by two 746 kW (1,000 hp) Piaggio P.XI R.C.40 radial piston engines.

- Ca.135 Tipo Peru

- Export version for Peru, six aircraft fitted with two 671 kW (900 hp) Isotta Fraschini Asso XI R.C.40 Spinto engines.

- Ca.135 bis/Alfa

- Single aircraft fitted with two 1,044 kW (1,400 hp) Alfa Romeo 135 R.C.32 Tornado radial piston engines.

- Ca.135 Raid

- A single Special long range version, fitted with extra fuel tanks, powered by two 736 kW (987 hp) Isotta Fraschini Asso XI engines.

- Ca 325

- A development of the Ca 135, powered by two 1,081 kW (1,450 hp) Isotta Fraschini Asso L.180 I.R.C.C.45 18-cylinder inline W engines, built in mock-up form only.[8]

Operators

- Belgian Air Component – license-built as SABCA S.45bis

- Regia Aeronautica operated 64 aircraft delivered since August 1936[9]

Specifications (Ca.135 P.XI)

Data from Italian Civil & Military Aircraft 1930–1945 [10]

General characteristics

- Crew: 4/5

- Length: 14.38 m (47 ft 2 in)

- Wingspan: 18.80 m (61 ft 8 in)

- Height: 3.40 m (11 ft 2 in)

- Empty weight: 6,051 kg (13,340 lb)

- Gross weight: 9,548 kg (21,050 lb)

- Powerplant: 2 × Piaggio P.XI R.C.40 14-cyl. two-row air-cooled radial piston engines, 746 kW (1,000 hp) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 365 km/h (227 mph, 197 kn) at 4,800 m (15,748 ft)

- Cruise speed: 349 km/h (217 mph, 189 kn)

- Range: 2,000 km (1,200 mi, 1,100 nmi)

- Service ceiling: 6,500 m (21,300 ft)

- Rate of climb: 5.6 m/s (1,100 ft/min)

- Time to altitude: 4,000 m (13,000 ft) in 11 min 36 s and to 5,000 m (16,000 ft) in 17 min 24s

Armament

- Guns: 3 x 12.7 mm (0.500 in) Breda-SAFAT machine guns

- Bombs: 1,474 kg (3,250 lb)

See also

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- Douglas B-23 Dragon

- Fiat BR.20

- Handley Page Hampden

- Heinkel He 111

- Lioré et Olivier LeO 45

- Mitsubishi Ki-21

- Piaggio P.32

- Vickers Wellington

Related lists

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Neulen 2000, p. 121.

- ↑ Neulen 2000, p. 124.

- ↑ Neulen 2000, pp. 124–125.

- ↑ Neulen 2000, pp. 125–126.

- ↑ Neulen 2000, pp. 126–127.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 The Latin American Aviation Historical Society: South American Aviation: "The Caproni Bergamaschi Ca.135 in Peruvian Service" by Amaru Tincopa Gallegos.

- 1 2 3 The Latin American Aviation Historical Society: South American Aviation: "Those Peruvian Ca. 135s" by Dan Hagedorn".

- ↑ Thompson, Jonathan W. (1963). Italian Civil and Military aircraft 1930–1945. New York: Aero Publishers Inc. ISBN 0-8168-6500-0.

- ↑ Caproni Ca.135

- ↑ Thompson, Jonathan (1963). Italian Civil and Military Aircraft 1930–1945. New York: Aero Publishers Inc. pp. 102–105. ISBN 0-8168-6500-0.

References

- Hagedorn, Dan (May 2000). "Les Caproni Ca.135 péruviens" [The Peruvian Caproni Ca.135s]. Avions: Toute l'Aéronautique et son histoire (in French) (86): 44–49. ISSN 1243-8650.

- Lembo, Daniele, Caproni Ca.135 Aerei nella Storia magazine, September 2006. (in Italian)

- Mondey, David, Axis Aircraft of World War II. Chancellor Press 1996. ISBN 1-85152-966-7

- Neulen, Hans Werner. In the skies of Europe – Air Forces allied to the Luftwaffe 1939–1945. Ramsbury, Marlborough, Crowood Press, 2000. ISBN 1-86126-799-1.

- Thompson, Jonathan (1963). Italian Civil & Military Aircraft 1930–1945. New York: Aero Publishers. pp. 102–105. ISBN 0-8168-6500-0.