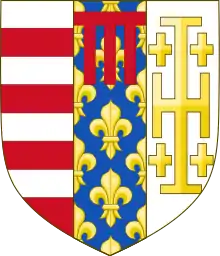

| Charles III (II) | |

|---|---|

Charles as depicted in the Chronica Hungarorum, 1488 | |

| King of Naples | |

| Reign | 12 May 1382 – 24 February 1386 |

| Coronation | 2 June 1381, Rome |

| Predecessor | Joanna I |

| Successor | Ladislaus |

| King of Hungary and Croatia | |

| Reign | 31 December 1385 – 24 February 1386 |

| Coronation | 31 December 1385, Székesfehérvár |

| Predecessor | Mary I |

| Successor | Mary I |

| Prince of Achaea | |

| Reign | 17 July 1383 – 24 February 1386 |

| Predecessor | James of Baux |

| Successor | Pedro de San Superano |

| Born | 1345 Durazzo, Kingdom of Naples |

| Died | 24 February 1386 (aged 41) Visegrád, Kingdom of Hungary |

| Spouse | Margaret of Durazzo |

| Issue More | Joanna II of Naples Ladislaus of Naples |

| House | Anjou-Durazzo |

| Father | Louis of Durazzo |

| Mother | Margaret of Sanseverino |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

Charles of Durazzo, also called Charles the Small (1345 – 24 February 1386), was King of Naples and the titular King of Jerusalem from 1382 to 1386 as Charles III, and King of Hungary from 1385 to 1386 as Charles II. In 1381, Charles created the chivalric Order of the Ship. In 1383, he succeeded to the Principality of Achaea on the death of James of Baux.

Life

Childhood and youth (1354/1357 – 1370)

He was the only child of Louis of Durazzo and his wife, Margaret of Sanseverino.[1][2][3] Louis of Durazzo was a younger son of John, Duke of Durazzo, who was the youngest son of King Charles II of Naples and Mary of Hungary.[4][5] Charles's date of birth is uncertain: he was born in 1354, according to historian Szilárd Süttő, and in 1357, according to Nancy Goldstone.[1][3] Charles was born in Durazzo.[6]

Louis of Durazzo rebelled against his cousins, Joanna I of Naples, and her husband, Louis of Taranto in the spring of 1360, but he was defeated.[3] He was also compelled to send the child Charles as a hostage to Queen Joanna I's court in Naples.[2][3] After Charles's father died in prison in the summer of 1362, Queen Joanna ordered that Charles was to be treated "with all honours due to the royal household and to maintain him in a royal state".[7]

Charles's distant cousin, Louis I of Hungary, who had not fathered a son, decided to invite Charles to Hungary.[8] Charles came to Hungary in 1364 or 1365.[2][9] King Louis initially planned to arrange a marriage between Charles and Anne, who was a daughter of Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor.[10] However, the negotiations of their marriage were broken off because the relations between Louis I and Charles IV had deteriorated.[11] Next, Louis proposed a marriage between Charles and Charles's cousin, Margaret of Durazzo, who was the youngest daughter of Queen Joanna's younger sister, Maria of Calabria.[12] Although the queen was opposed to the marriage, Pope Urban VI granted the papal dispensation that was necessary for the marriage on 15 June 1369.[12] Their marriage took place in Naples on 24 January 1370.[12][11]

Louis made Charles governor of Slavonia, Croatia and Dalmatia with the title of duke in 1371.[2][9][13]

War for Naples (1379–1381)

Queen Joanna I of Naples officially acknowledged Clement VII as the lawful pope against Urban VI on 22 November 1378.[14] She even gave shelter to Clement VII, who had been expelled from Rome, and helped him to leave Italy for Avignon in May 1379.[15] In retaliation, Pope Urban VI excommunicated the queen and declared her deprived of her kingdom in favor of Charles of Durazzo and his wife Margaret on 17 June.[16][17]

The conflict between Joanna and Pope Urban VI caused the Pope (as feudal overlord of the kingdom) to declare her dethroned in 1381 and give the kingdom to Charles. He marched on the Kingdom of Naples with a Croatian army, defeated her husband Otto, Duke of Brunswick-Grubenhagen, at San Germano, seized the city and besieged Joanna in the Castel dell'Ovo. After Otto's failed attempt to relieve her, Charles captured her and had her imprisoned at San Fele. Soon afterwards, when news reached Charles that her adopted heir, Louis I of Anjou, was setting out on an expedition to reconquer Naples, Charles had the Queen strangled in prison in 1382. Then he succeeded to the crown.

King of Naples (1382–1385)

Louis's expedition counted to some 40,000 troops, including those of Amadeus VI of Savoy, and had the financial support of Antipope Clement VII and Bernabò Visconti of Milan. Charles, who counted on the mercenary companies under John Hawkwood and Bartolomeo d'Alviano, for a total of some 14,000 men, was able to divert the French from Naples to other regions of the kingdom and to harass them with guerrilla tactics. Amadeus fell ill and died in Molise on 1 March 1383, and his troops abandoned the field. Louis asked for help to his king in France, who sent him an army under Enguerrand VII, Lord of Coucy. The latter was able to conquer Arezzo and then invade the Kingdom of Naples, but midway was reached by the news that Louis had suddenly died at Bisceglie on 20 September 1384.

In the meantime, relationships with Urban VI became strained, as he suspected that Charles was plotting against him. In January 1385 he had six cardinals arrested, and one, under torture, revealed Charles's part in a conspiracy. He then excommunicated Charles and his wife, and imposed an interdict over the Kingdom of Naples. The King replied by sending Alberico da Barbiano to besiege the pope in Nocera. After six months of siege, Urban was freed by two Neapolitan barons who had sided with Louis of Anjou, Raimondello Orsini and Tommaso di Sanseverino.

Succession in Hungary

While Urban took refuge in Genoa, Charles left the Kingdom to move to Hungary. Upon the death of King Louis I, he claimed the Hungarian throne as the senior Angevin male and ousted Louis's daughter Mary of Hungary in December 1385. It was not difficult for him to take power, as he gained the support of several Croatian lords and many contacts he made during his tenure as Duke of Croatia and Dalmatia. However, Elizabeth of Bosnia, widow of Louis and mother of Mary, arranged to have Charles assassinated on 7 February 1386. He died of his wounds at Visegrád on 24 February.

He was buried in Visegrád without religious ceremony, because of his still valid excommunication by Pope Urban VI. His son Ladislaus (named in honor of the King-Knight Saint Ladislaus I of Hungary) succeeded him in Naples, while the regents of Mary of Hungary reinstated her as Queen of Hungary. However, Ladislaus would try to obtain the crown of Hungary in the future.

Children

Charles III and Margaret of Durazzo had three children:

- Mary of Durazzo (1369–1371).

- Joanna II of Naples (23 June 1373 – 2 February 1435).

- Ladislaus of Naples (11 February 1377 – 6 August 1414).

References

- 1 2 Süttő 2002, p. 77.

- 1 2 3 4 Csukovits 2012, p. 122.

- 1 2 3 4 Goldstone 2009, p. 202.

- ↑ Süttő 2002, pp. 77–78.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 383.

- ↑ Giovanni Tarcagnota (1566). Del sito, et lodi della citta di Napoli con una breve historia de gli re suoi, et delle cose pui degne altrove ne' medesimi tempi abvenute. Scotto Gis. Maria. p. 77.

- ↑ Goldstone 2009, p. 209.

- ↑ Süttő 2002, p. 78.

- 1 2 Engel 2001, p. 169.

- ↑ Süttő 2002, pp. 78–79.

- 1 2 Süttő 2002, p. 79.

- 1 2 3 Goldstone 2009, p. 250.

- ↑ Fügedi 1986, p. 15.

- ↑ Goldstone 2009, p. 290.

- ↑ Goldstone 2009, p. 291.

- ↑ Goldstone 2009, p. 292.

- ↑ Tuchman 1978, p. 399.

Sources

- Csukovits, Enikő (2012). "II. (Kis) Károly [Charles II the Small]". In Gujdár, Noémi; Szatmáry, Nóra (eds.). Magyar királyok nagykönyve: Uralkodóink, kormányzóink és az erdélyi fejedelmek életének és tetteinek képes története [Encyclopedia of the Kings of Hungary: An Illustrated History of the Life and Deeds of Our Monarchs, Regents and the Princes of Transylvania] (in Hungarian). Reader's Digest. pp. 122–125. ISBN 978-963-289-214-6.

- Engel, Pál (2001). The Realm of St Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895–1526. I.B. Tauris Publishers. ISBN 1-86064-061-3.

- Fine, John V. A. Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4.

- Fügedi, Erik (1986). "Könyörülj, bánom, könyörülj ..." ["Have Mercy on Me, My Ban, Have Mercy ..."]. Helikon. ISBN 963-207-662-1.

- Goldstone, Nancy (2009). The Lady Queen: The Notorious Reign of Joanna I, Queen of Naples, Jerusalem, and Sicily. Walker&Company. ISBN 978-0-8027-7770-6.

- Michaud, Claude (2000). "The kingdoms of Central Europe in the fourteenth century". In Jones, Michael (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume VI: c. 1300–c. 1415. Cambridge University Press. pp. 735–763. ISBN 0-521-36290-3.

- Solymosi, László; Körmendi, Adrienne (1981). "A középkori magyar állam virágzása és bukása, 1301–1506 [The Heyday and Fall of the Medieval Hungarian State, 1301–1526]". In Solymosi, László (ed.). Magyarország történeti kronológiája, I: a kezdetektől 1526-ig [Historical Chronology of Hungary, Volume I: From the Beginning to 1526] (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 188–228. ISBN 963-05-2661-1.

- Süttő, Szilárd (2002). "II. Károly (Charles the Small)". In Kristó, Gyula (ed.). Magyarország vegyes házi királyai [The Kings of Various Dynasties of Hungary] (in Hungarian). Szukits Könyvkiadó. pp. 77–84. ISBN 963-9441-58-9.

- Tuchman, Barbara W. (1978). A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century. Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-34957-1.

External links

- Armorial of the House Anjou-Sicily (in French)

- House of Anjou-Sicily (in French)

.svg.png.webp)