Duchy of Bavaria | |

|---|---|

| c. 555–1805 | |

| |

.svg.png.webp) | |

.svg.png.webp) Duchy of Bavaria within the Holy Roman Empire, 1618 | |

| Status | Stem duchy and vassal of the Merovingians (the so-called older stem duchy) (c. 555–788) Direct rule under the Carolingians, as Kings of Bavaria (788–843) Stem duchy of East Francia and the Kingdom of Germany (the so-called younger stem duchy) (843–962) State of the Holy Roman Empire (from 962) |

| Capital | Regensburg (until 1255) Munich (from 1505) |

| Common languages | Bavarian, Latin |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism (official) Lutheranism |

| Demonym(s) | Bavarian |

| Government | Feudal monarchy |

| Duke | |

| Historical era | Medieval Europe |

| c. 555 | |

• Directly ruled part of the Carolingian Empire | 788 |

| 907 | |

• Carinthia split off | 976 |

| 1156 | |

• To House of Wittelsbach | 1180 |

• First partition | 1255 |

| 1503 | |

• Raised to Electorate | 1623 |

| 1805 | |

| Today part of | |

The Duchy of Bavaria (German: Herzogtum Bayern) was a frontier region in the southeastern part of the Merovingian kingdom from the sixth through the eighth century. It was settled by Bavarian tribes and ruled by dukes (duces) under Frankish overlordship. A new duchy was created from this area during the decline of the Carolingian Empire in the late ninth century. It became one of the stem duchies of the East Frankish realm which evolved as the Kingdom of Germany and the Holy Roman Empire.

During internal struggles of the ruling Ottonian dynasty, the Bavarian territory was considerably diminished by the separation of the newly established Duchy of Carinthia in 976. Between 1070 and 1180 the Holy Roman Emperors were again strongly opposed by Bavaria, especially by the ducal House of Welf. In the final conflict between the Welf and Hohenstaufen dynasties, Duke Henry the Lion was banned and deprived of his Bavarian and Saxon fiefs by Emperor Frederick Barbarossa. Frederick passed Bavaria over to the House of Wittelsbach, which held it until 1918. The Bavarian dukes were raised to prince-electors during the Thirty Years' War in 1623, and to kings by Napoleon in 1806. The duchy chaired the bench of the secular princes to the Reichstag of the Empire.

Geography

The medieval Bavarian stem duchy covered present-day Southeastern Germany and most parts of Austria along the Danube river, up to the Hungarian border which then ran along the Leitha tributary in the east. It included the Altbayern regions of the modern state of Bavaria, with the lands of the Nordgau march (the later Upper Palatinate), but without its Swabian and Franconian regions. The separation of the Duchy of Carinthia in 976 entailed the loss of large East Alpine territories covering the present-day Austrian states of Carinthia and Styria as well as the adjacent Carniolan region in today's Slovenia. The eastern March of Austria —roughly corresponding to the present state of Lower Austria— was likewise elevated to a duchy in its own right by 1156.

Over the centuries, several further seceded territories in the territory of the former stem duchy, such as the County of Tyrol or the Archbishopric of Salzburg, gained Imperial immediacy. From 1500, a number of these Imperial states were members of the Bavarian Circle of the Holy Roman Empire.

History

Older stem duchy

The origins of the older Bavarian duchy can be traced to the year 551/555. In his Getica, the chronicler Jordanes writes: "That area of the Swabians has the Bavarii in the east, the Franks in the west ..."

Agilolfings

Until the end of the first duchy, all rulers descended from the family of the Agilolfings. The Bavarians then colonized the area from the March of the Nordgau along the Naab river (later called the Upper Palatinate) up to the Enns in the east and southward across the Brenner Pass to the Upper Adige in present-day South Tyrol. The first documented duke was Garibald I, a scion of the Frankish Agilolfings, who ruled from 555 onward as a largely independent Merovingian vassal.

On the eastern border, changes occurred with the departure of the West Germanic Lombard tribes from the Pannonian basin to northern Italy in 568 and the succession of the Avars, as well as with the settlement of West Slavic Czechs on the adjacent territory beyond the Bohemian Forest at about the same time. At around 743, the Bavarian duke Odilo vassalised the Slavic princes of Carantania (roughly corresponding with the later March of Carinthia), who had asked him for protection against the invading Avars. The residence of the largely independent Agilolfing dukes was then Regensburg, the former Roman Castra Regina, on the Danube river.

During Christianization, Bishop Corbinian laid the foundations for the later Diocese of Freising before 724; Saint Kilian in the 7th century had been a missionary of the Franconian territory in the north, then ruled by the Dukes of Thuringia, where Boniface founded the Diocese of Würzburg in 742. In the adjacent Alamannic (Swabian) lands west of the Lech river, Augsburg was a bishop's seat. When Boniface established the Diocese of Passau in 739, he could already build on local Early Christian traditions. In the south, Saint Rupert had founded in 696 the Diocese of Salzburg, probably after he had baptized Duke Theodo of Bavaria at his court in Regensburg, becoming the "Apostle of Bavaria". In 798 Pope Leo III created the Bavarian ecclesiastical province with Salzburg as metropolitan seat and Regensburg, Passau, Freising and Säben (later Brixen) as suffragan dioceses.

Carolingians

With the rise of the Frankish Empire under the Carolingian dynasty, the autonomy of the Bavarian dukes, previously enjoyed under the Merovingians, was reduced and subsequently terminated. In 716 the Carolingians had incorporated the Franconian lands in the north, formerly held by the Dukes of Thuringia, whereby the bishops of Würzburg gained a dominant position. In the west, the Carolingian mayor of the palace Carloman had suppressed the last Alamannic revolt at the 746 Blood court at Cannstatt. The last tribal stem duchy to be incorporated was Bavaria in 788, after Duke Tassilo III had tried in vain to maintain his independence through an alliance with the Lombards. The conquest of the Lombard Kingdom by Charlemagne entailed the fall of Tassilo, who was deposed in 788. From that point, Bavaria was administered by Frankish prefects, first of whom was Gerold, who governed Bavaria from 788 to 799.[1]

By establishing direct rule over Bavaria, the Franks provoked the neighbouring Avars. At that time, the eastern Bavarian border, towards the Avars, was situated on the river Enns. Already in 788, the Avars made an incursion into Bavaria, but Franko-Bavarian forces repelled them, and then launched a counterattack towards neighbouring Avarian regions, situated along the river Danube, east of the Enns. The two sides clashed near the river Ybbs, on the Ybbs Field (German: Ybbsfeld), where the Avars suffered a significant defeat (788).[2][3]

In order to secure Bavaria's eastern borders, and resolve other political and administrative questions, Charlemagne came to Bavaria in person, during the autumn of the same year (788). In Regensburg, he held a council and regulated issues regarding the Bavarian frontier counties (marches),[4] thus preparing the basis for future actions in the east. In 790, the Avars tried to negotiate a peace settlement with the Franks, but no agreement was reached.[5]

Bavaria then became the main base for Frankish campaign against the Avars, which was initiated in 791. A large Frankish army, personally led by Charlemagne, crossed from Bavaria in to the Avarian territory beyond the river Enns, and started to advance along the river Danube, divided in two columns, but found no active resistance, and soon reached the region of Vienna Woods, at the very gates of the Pannonian Plain. No decisive battles were fought, since the Avars had fled before the advancing Frankish army.[6]

Frankish acquisition of new eastern regions, particularly those between the river Enns and the Vienna Woods, represented a significant gain for the security of Bavaria. At first, that territory was placed under the jurisdiction of the Bavarian prefect Gerold (d. 799),[7] and subsequently organized as a frontier unit, that became known as the (Bavarian) Eastern March (Latin: marcha orientalis). It provided safety for Bavaria's eastern borders, securing as well the main communication between Frankish possessions in Bavaria and Pannonia.[8]

Younger stem duchy

In his 817 Ordinatio Imperii, Charlemagne's son and successor Emperor Louis the Pious tried to maintain the unity of the Carolingian Empire: while imperial authority upon his death was to pass to his eldest son Lothair I, the younger brothers were to receive subordinate realms. From 825 Louis the German styled himself "King of Bavaria" in the territory that was to become the centre of his power. When the brothers divided the Empire by the 843 Treaty of Verdun, Bavaria became part of East Francia under King Louis the German, who upon his death bequested the Bavarian royal title to his eldest son Carloman in 876. Carloman's natural son Arnulf of Carinthia, raised in the former Carantanian lands, secured possession of the March of Carinthia upon his father's death in 880 and became King of East Francia in 887. Carinthia and Bavaria were the bases of his power, with Regensburg as the seat of his government.

Due mainly to the support of the Bavarians, Arnulf could take the field against Charles in 887 and secure his own election as German king in the following year. In 899 Bavaria passed to Louis the Child, during whose reign continuous Hungarian ravages occurred. Resistance to these inroads became gradually feebler, and tradition has it that on 5 July 907 almost the whole of the Bavarian tribe perished in the Battle of Pressburg against these formidable enemies.

During the reign of Louis the Child, Luitpold, Count of Scheyern, who possessed large Bavarian domains, ruled the Mark of Carinthia, created on the southeastern frontier for the defence of Bavaria. He died in the great battle of 907, but his son Arnulf, surnamed the Bad, rallied the remnants of the tribe in alliance with the Hungarians and became duke of the Bavarians in 911, uniting Bavaria and Carinthia under his rule. The German king Conrad I unsuccessfully attacked Arnulf when the latter refused to acknowledge his royal supremacy.

Luitpoldings and Ottonians

The Carolingian reign in East Francia ended in 911 when Arnulf's son, King Louis the Child, died without heirs. The discontinuation of the central authority led to a new strengthening of the German stem duchies. At the same time, East Francia was exposed to the rising threat from Hungarian invasions, especially in the Bavarian March of Austria (marchia orientalis) beyond the Enns river. In 907 the army of Luitpold, Margrave of Bavaria suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Pressburg. Luitpold himself was killed in action and his son Arnulf the Bad assumed the ducal title, becoming the first Duke of Bavaria from the Luitpolding dynasty. However, the Austrian march remained occupied by the Hungarians and the Pannonian lands were irrecoverably lost.

Nevertheless, the self-confidence of the Bavarian dukes was an ongoing matter of dispute in the newly established Kingdom of Germany: Duke Arnulf's son Eberhard was deposed by King Otto I of Germany in 938; he was succeeded by his younger brother Berthold. In 948, King Otto finally disempowered the Luitpoldings and installed his younger brother Henry I as Bavarian duke. The late Duke Berthold's minor heir, Henry III, was fobbed off with the office of a Bavarian Count palatine. The last attempt of the Luitpoldings to regain power by joining the rebellion of King Otto's son Duke Liudolf of Swabia was crushed in 954.

In 952 Duke Henry I also received the Italian March of Verona, which Otto I had seized from King Berengar II of Italy. He still had to deal with the Hungarian threat, which was not eliminated until King Otto's victory at the 955 Battle of Lechfeld. The Magyars retreated behind the Leitha and Morava rivers, facilitating a second wave of German Ostsiedlung into the areas of today's Lower Austria, Istria and Carniola. Although ruled by the Ottonian descendants of Henry I, a cadet branch of the Saxon royal dynasty, the conflict of the Bavarian dukes with the German (from 962: Imperial) court continued: in 976, Emperor Otto II deposed his rebellious cousin Duke Henry II of Bavaria and established the Duchy of Carinthia on former Bavarian territory granted to the former Luitpolding Count palatine Henry III, who also became Margrave of Verona. Though Henry II reconciled with Emperor Otto's widow Theophanu in 985 and regained his duchy, the power of the Bavarian dukes was further diminished by the rise of the Franconian House of Babenberg, ruling as Margraves of Austria (Ostarrichi), who became increasingly independent.

House of Welf

The last Ottonian duke, Henry IV of Bavaria, was elected King of the Romans in 1002 as Henry II. At different times, the duchy was ruled by the German kings in personal union, by dependent dukes, or even by the emperor's sons, a tradition maintained by Henry's Salian successors. This period saw the rise of many aristocratic families, such as the Counts of Andechs and the House of Wittelsbach. In 1061, the dowager empress Agnes of Poitou enfeoffed the Saxon count Otto of Nordheim with the Duchy. Nevertheless, her son King Henry IV seized the duchy on fallacious grounds, which ultimately led to the Saxon Rebellion of 1073. Henry entrusted Bavaria to Welf, a scion of the Veronese margravial House of Este and progenitor of the Welf dynasty, which intermittently ruled the duchy for the next 110 years.

Only with the establishment of Welf rule as dukes from 1070 by Henry IV was there a re-emergence of the Bavarian dukes. This period is characterized by the Investiture Controversy between Emperor and Pope, which strengthened Welf rule through siding with the pope's position.

After Henry V, the last of the Salian emperors, died in 1125, Lothair III of the House of Supplinburg was elected to the thrown; the Bavarian duke Henry the Proud had married Lothair's daughter Gertrude, and was thus promised her inheritance. When conflict arose with anti-king Conrad III, nephew of Henry V and member of the Swabian House of Hohenstaufen, the Bavarian duke threw his support behind Lothair, further increasing his social capital and increasing his chances of election as King of Germany as well as Duke of Saxony in the aftermath of Lothair's death. However, Conrad III was successfully elected as King of Germany in 1138; fearing Henry's power, Conrad denied Henry his investiture with the Duchy of Saxony, claiming that it was unlawful for a duke to hold two duchies.[9] This, compounded with his bitterness for being denied the throne, prompted Henry to refuse to swear his oath of allegiance to Conrad. As a consequence, he was dispossessed of all of his territories, and Bavaria was given to his Babenberg half-brother Leopold IV, Margrave of Austria in 1139.

The Duchy of Swabia consisted largely of countryside during the reign of the Staufer king, while Franconia became the center of Staufer power, having been invested with the title dux Francorum orientalium, in 1115 by Henry V. This lasted until 1168, when the Bishop of Würzburg acquired the diocese of Bamberg and thus became the Duke of Franconia. The Hohenstaufen Frederick I Barbarossa attempted reconciliation with the Welfs[10] and, in 1156, gave back the Duchy of Bavaria to the Welf Henry the Lion; however, the East Mark remained in Babenberg hands, and it was thus elevated to the Duchy of Austria as compensation for the loss of Bavaria.[11] The elevation of the Marcha Orientalis under the Babenbergs to a Dukedom established it as the nucleus of the later state of Austria (Ostarrichi).

Henry the Lion founded numerous cities, including Munich in 1158. Through his strong position as ruler of the two duchies of Saxony and Bavaria, he came into conflict with Frederick I Barbarossa. With the banishment of Henry the Lion and the separation of the March of Styria from Bavaria—raised to the Duchy of Styria in 1180 under Margrave Ottokar IV—the younger tribal duchy came to an end.

Wittelsbachs

From 1180 to 1918, the Wittelsbachs were the rulers of Bavaria, as dukes, later as electors and kings. When Count Palatine Otto VI. of Wittelsbach became Otto I, Duke of Bavaria in 1180, the Wittelsbach treasury was rather low. In the following years it was significantly augmented by purchase, marriage, and inheritance. Newly acquired land was no longer given as a fief, but managed by servants. Also, powerful families, such as the counts of Andechs, died out during this period. Otto's son Ludwig I of Wittelsbach was enfeoffed in 1214 with the County Palatine of the Rhine.

Since there was no preference for succession of the firstborn in the Wittelsbach dynasty, in contrast to many governments of this time, there was in 1255 a division of the land into Upper Bavaria with the Palatinate and the Nordgau (headquartered in Munich) and Lower Bavaria (with seats in Landshut and Burghausen). There is still today a distinction made between upper and lower Bavaria (cf. Regierungsbezirke) .

Despite renewed division after a short time of reunification, Bavaria gained new heights of power with Louis IV, Holy Roman Emperor, who became the first Wittelsbach emperor in 1328. The newly gained areas of Brandenburg (1323), Tyrol (1342), the Dutch provinces Holland, Zeeland and Friesland and the Hainaut (1345) were, however, lost under his successors. In 1369, Tyrol fell through the Treaty of Schärding to the Habsburgs. The Luxemburgish rider followed in 1373 and the Dutch counties fell to Burgundy in 1436. In the 1329 Treaty of Pavia, Emperor Louis divided ownership in a Palatine region, with the Rhine Palatinate, and a later so-called Upper Palatinate. Thus, the electoral dignity for the line was passed onwards to the Palatinate. With the recognition of the limits of domination by the Bavarian Duke in the year 1275, Salzburg of Bavaria went into their final phase. When the Salzburg Archbishop issued its own country regulations in 1328, Salzburg become a largely independent state within the Holy Roman Empire.

.png.webp)

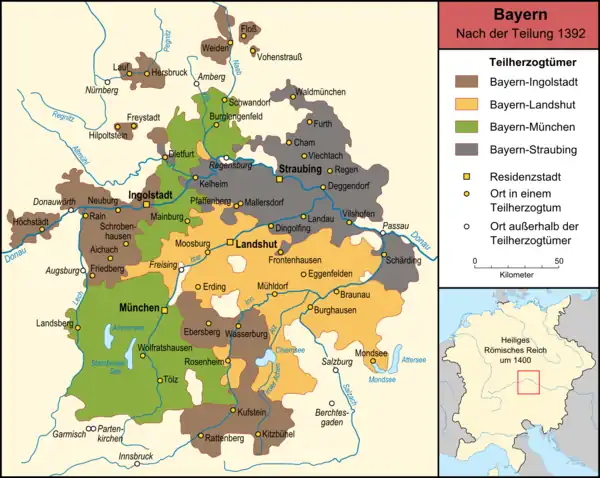

In the 14th and 15th centuries, upper and lower Bavaria were repeatedly subdivided. Four Duchies existed after the division of 1392: Bavaria-Straubing, Bavaria-Landshut, Bavaria-Ingolstadt and Bavaria-Munich. These dukes often waged war against each other. Duke Albrecht IV of Bavaria-Munich united Bavaria in 1503 through war and primogeniture. However, the originally Bavarian offices Kufstein, Kitzbühel and Rattenberg in Tirol were lost in 1504.

In spite of the decree of 1506, Albert's oldest son William IV was compelled to grant a share in the government in 1516 to his brother Louis X, an arrangement which lasted until the death of Louis in 1545. William followed the traditional Wittelsbach policy of opposition to the Habsburgs until in 1534 he made a treaty at Linz with Ferdinand I, the king of Hungary and Bohemia. This link strengthened in 1546, when the emperor Charles V obtained the help of the duke during the war of the league of Schmalkalden by promising him in certain eventualities the succession to the Bohemian throne, and the electoral dignity enjoyed by the count palatine of the Rhine. William also did much at a critical period to secure Bavaria for Catholicism. The reformed doctrines had made considerable progress in the duchy when the duke obtained extensive rights over the bishoprics and monasteries from the pope. He then took measures to repress the reformers, many of whom were banished; while the Jesuits, whom he invited into the duchy in 1541, made the Jesuit College of Ingolstadt, their headquarters in Germany. William died in March 1550 and was succeeded by his son Albert V, who had married a daughter of Ferdinand I. Early in his reign Albert made some concessions to the reformers, who were still strong in Bavaria; but about 1563 he changed his attitude, favoured the decrees of the Council of Trent, and pressed forward the work of the Counter-Reformation. As education passed by degrees into the hands of the Jesuits, the progress of Protestantism was effectually arrested in Bavaria.

The succeeding duke, Albert's son, William V, had received a Jesuit education and showed keen attachment to Jesuit tenets. He secured the Archbishopric of Cologne for his brother Ernest in 1583, and this dignity remained in the possession of the family for more than 200 years. In 1597 he abdicated in favour of his son Maximilian I.

Maximilian I found the duchy encumbered with debt and filled with disorder, but ten years of his vigorous rule effected a remarkable change. The finances and the judicial system were reorganised, a class of civil servants and a national militia founded, and several small districts were brought under the duke's authority. The result was a unity and order in the duchy which enabled Maximilian to play an important part in the Thirty Years' War; during the earlier years of which he was so successful as to acquire the Upper Palatinate and the electoral dignity which had been enjoyed since 1356 by the elder branch of the Wittelsbach family. The Electorate of Bavaria then consisted of most of the modern regions of Upper Bavaria, Lower Bavaria, and the Upper Palatinate.

See also

References

- ↑ Bowlus 1995, pp. 86.

- ↑ Bowlus 1995, pp. 47, 80.

- ↑ Pohl 2018, pp. 378–379.

- ↑ Nelson 2019, pp. 14, 257.

- ↑ Pohl 2018, pp. 379.

- ↑ Schutz 2004, p. 61.

- ↑ Bowlus 1995, pp. 74, 86.

- ↑ Bowlus 1995, pp. 24, 45, 85, 101.

- ↑ Chisholm, Hugh (1911). Henry "The Proud". Vol. 13. Cambridge University Press. p. 293.

- ↑ Görich, Knut: Die Staufer. Herrscher und Reich. Munich 2006. p. 41.

- ↑ Emmerson, Richard K. (2013). Key Figures in Medieval Europe: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 320. ISBN 978-1-136-77518-5.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bavaria". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Sources

- Bowlus, Charles R. (1995). Franks, Moravians, and Magyars: The Struggle for the Middle Danube, 788–907. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812232769.

- Goldberg, Eric J. (2006). Struggle for Empire: Kingship and Conflict under Louis the German, 817-876. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801438905.

- Nelson, Janet L. (2019). King and Emperor: A New Life of Charlemagne. London. ISBN 9780520314207.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Pertz, Georg Heinrich, ed. (1845). Einhardi Annales. Hanover.

- Pohl, Walter (1995). Die Welt der Babenberger: Schleier, Kreuz und Schwert. Graz: Verlag Styria. ISBN 9783222123344.

- Pohl, Walter (2018). The Avars: A Steppe Empire in Central Europe, 567-822. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9781501729409.

- Reuter, Timothy (2013) [1991]. Germany in the Early Middle Ages c. 800–1056. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781317872399.

- Schutz, Herbert (2004). The Carolingians in Central Europe, Their History, Arts, and Architecture: A Cultural History of Central Europe, 750-900. Leiden-Boston: BRILL. ISBN 9004131493.

- Scholz, Bernhard Walter, ed. (1970). Carolingian Chronicles: Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard's Histories. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472061860.

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)