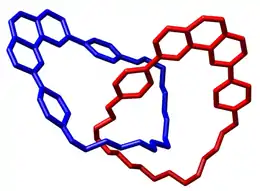

In macromolecular chemistry, a catenane (from Latin catena 'chain') is a mechanically interlocked molecular architecture consisting of two or more interlocked macrocycles, i.e. a molecule containing two or more intertwined rings. The interlocked rings cannot be separated without breaking the covalent bonds of the macrocycles. They are conceptually related to other mechanically interlocked molecular architectures, such as rotaxanes, molecular knots or molecular Borromean rings. Recently the terminology "mechanical bond" has been coined that describes the connection between the macrocycles of a catenane. Catenanes have been synthesised in two different ways: statistical synthesis and template-directed synthesis.

Synthesis

There are two primary approaches to the organic synthesis of catenanes. The first is to simply perform a ring-closing reaction with the hope that some of the rings will form around other rings giving the desired catenane product. This so-called "statistical approach" led to the first synthesis of a catenane; however, the method is highly inefficient, requiring high dilution of the "closing" ring and a large excess of the pre-formed ring, and is rarely used.

The second approach relies on supramolecular preorganization of the macrocyclic precursors utilizing hydrogen bonding, metal coordination, hydrophobic effect, or coulombic interactions. These non-covalent interactions offset some of the entropic cost of association and help position the components to form the desired catenane upon the final ring-closing. This "template-directed" approach, together with the use of high-pressure conditions, can provide yields of over 90%, thus improving the potential of catenanes for applications. An example of this approach used bis-bipyridinium salts which form strong complexes threaded through crown ether bis(para-phenylene)-34-crown-10.[3]

Template directed syntheses are mostly performed under kinetic control, when the macrocyclization (catenation) reaction is irreversible. More recently, the groups of Sanders and Otto have shown that dynamic combinatorial approaches using reversible chemistry can be particularly successful in preparing new catenanes of unpredictable structure.[4] The thermodynamically controlled synthesis provides an error correction mechanism; even if a macrocycle closes without forming a catenane it can re-open and yield the desired interlocked structure later. The approach also provides information on the affinity constants between different macrocycles thanks to the equilibrium between the individual components and the catenanes, allowing a titration-like experiment.[5]

Properties and applications

A particularly interesting property of many catenanes is the ability of the rings to rotate with respect to one another. This motion can often be detected and measured by NMR spectroscopy, among other methods. When molecular recognition motifs exist in the finished catenane (usually those that were used to synthesize the catenane), the catenane can have one or more thermodynamically preferred positions of the rings with respect to each other (recognition sites). In the case where one recognition site is a switchable moiety, a mechanical molecular switch results. When a catenane is synthesized by coordination of the macrocycles around a metal ion, then removal and re-insertion of the metal ion can switch the free motion of the rings on and off.

If there are more than one recognition sites it is possible to observe different colors depending on the recognition site the ring occupies and thus it is possible to change the color of the catenane solution by changing the preferred recognition site.[6] Switching between the two sites may be achieved by the use of chemical, electrochemical or even visible light based methods.

Catenanes have been synthesized incorporating many functional units, including redox-active groups (e.g. viologen, TTF=tetrathiafulvalene), photoisomerizable groups (e.g. azobenzene), fluorescent groups and chiral groups.[7] Some such units have been used to create molecular switches as described above, as well as for the fabrication of molecular electronic devices and molecular sensors.

Families

There are a number of distinct methods of holding the precursors together prior to the ultimate ring-closing reaction in a template-directed catenane synthesis. Each noncovalent approach to catenane formation results in what can be considered different families of catenanes.

Another family of catenanes are called pretzelanes or bridged [2]catenanes after their likeness to pretzels with a spacer linking the two macrocycles. In one such system[8] one macrocycle is an electron deficient oligo Bis-bipyridinium ring and the other cycle is crown ether cyclophane based on para phenylene or naphthalene. X-ray diffraction shows that due to pi-pi interactions the aromatic group of the cyclophane is held firmly inside the pyridinium ring. A limited number of (rapidly interchanging) conformers exist for this type of compound.

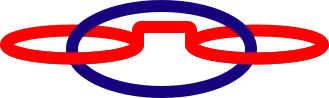

In handcuff-shaped catenanes,[9] two connected rings are threaded through the same ring. The bis-macrocycle (red) contains two phenanthroline units in a crown ether chain. The interlocking ring is self-assembled when two more phenanthroline units with alkene arms coordinate through a copper(I) complex followed by a metathesis ring closing step.

Catenanes |

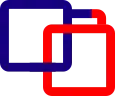

Pretzelanes |

Handcuff-shaped catenanes |

Nomenclature

In catenane nomenclature, a number in square brackets precedes the word "catenane" in order to indicate how many rings are involved.[10] Discrete catenanes up to a [7]catenane have been synthesised.[11]

See also

References

- ↑ Ashton, Peter R.; Brown, Christopher L.; Chrystal, Ewan J. T.; Goodnow, Timothy T.; Kaifer, Angel E.; Parry, Keith P.; Philp, Douglas; Slawin, Alexandra M. Z.; Spencer, Neil; Stoddart, J. Fraser; Williams, David J. (1991). "The self-assembly of a highly ordered [2]catenane". Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications (9): 634. doi:10.1039/C39910000634.

- ↑ Cesario, M.; Dietrich-Buchecker, C. O.; Guilhem, J.; Pascard, C.; Sauvage, J. P. (1985). "Molecular structure of a catenand and its copper(I) catenate: complete rearrangement of the interlocked macrocyclic ligands by complexation". Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications (5): 244. doi:10.1039/C39850000244.

- ↑ Ashton, Peter R.; Goodnow, Timothy T.; Kaifer, Angel E.; Reddington, Mark V.; Slawin, Alexandra M. Z.; Spencer, Neil; Fraser Stoddart, J.; Vicent, Cristina; Williams, David J. (1989-10-01). "Ein [2]-Catenan auf Bestellung". Angewandte Chemie. 101 (10): 1404–1408. Bibcode:1989AngCh.101.1404A. doi:10.1002/ange.19891011023. ISSN 1521-3757.

- ↑ T. S. R. Lam; A. Belenguer; S. L. Roberts; C. Naumann; T. Jarrosson; S. Otto; J. K. M. Sanders (April 2005). "Amplification of acetylcholine-binding catenanes from dynamic combinatorial libraries". Science. 308 (5722): 667–669. Bibcode:2005Sci...308..667L. doi:10.1126/science.1109999. PMID 15761119. S2CID 30506228.

- ↑ Li, J.; Nowak, P.; Fanlo-Virgos, H.; Otto, S. (2014). "Catenanes from Catenanes: Quantitative Assessment of Cooperativity in Dynamic Combinatorial Catenation". Chem. Sci. 5 (12): 4968–4974. doi:10.1039/C4SC01998A. hdl:11370/97ed22a2-ef35-42f8-bbef-34f2f32e2cb3.

- ↑ Sun, Junling; Wu, Yilei; Liu, Zhichang; Cao, Dennis; Wang, Yuping; Cheng, Chuyang; Chen, Dongyang; Wasielewski, Michael R.; Stoddart, J. Fraser (2015-06-18). "Visible Light-Driven Artificial Molecular Switch Actuated by Radical–Radical and Donor–Acceptor Interactions". The Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 119 (24): 6317–6325. Bibcode:2015JPCA..119.6317S. doi:10.1021/acs.jpca.5b04570. ISSN 1089-5639. PMID 25984816.

- ↑ Jamieson, E. M. G.; Modicom, F.; Goldup, S. M. (2018). "Chirality in rotaxanes and catenanes". Chemical Society Reviews. 47 (14): 5266–5311. doi:10.1039/C8CS00097B. PMC 6049620. PMID 29796501.

- ↑ Liu, Y.; Vignon, S. A.; Zhang, X.; Bonvallet, P. A.; Khan, S. I.; Houk, K. N.; Stoddart, J. F. (November 2005). "Dynamic Chirality in Donor−Acceptor Pretzelanes". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 70 (23): 9334–9344. doi:10.1021/jo051430g. PMID 16268606.

- ↑ Frey, Julien; Kraus, Tomáš; Heitz, Valérie; Sauvage, Jean-Pierre (2005). "A catenane consisting of a large ring threaded through both cyclic units of a handcuff-like compound". Chemical Communications (42): 5310–2. doi:10.1039/B509745B. PMID 16244738.

- ↑ Safarowsky, O.; Windisch, B.; Mohry, A.; Vögtle, F. (June 2000). "Nomenclature for Catenanes, Rotaxanes, Molecular Knots, and Assemblies Derived from These Structural Elements". Journal für Praktische Chemie. 342 (5): 437–444. doi:10.1002/1521-3897(200006)342:5<437::AID-PRAC437>3.0.CO;2-7.

- ↑ Black, Samuel P.; Stefankiewicz, Artur R.; Smulders, Maarten M. J.; Sattler, Dominik; Schalley, Christoph A.; Nitschke, Jonathan R.; Sanders, Jeremy K. M. (27 May 2013). "Generation of a Dynamic System of Three-Dimensional Tetrahedral Polycatenanes". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 52 (22): 5749–5752. doi:10.1002/anie.201209708. PMC 4736444. PMID 23606312.

External links

Media related to Catenanes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Catenanes at Wikimedia Commons