| Saint Stephen of Bourges Saint-Étienne de Bourges | |

|---|---|

Bourges Cathedral | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Roman Catholic Church |

| Province | Archdiocese of Bourges |

| Region | Centre-Val de Loire |

| Rite | Roman |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Cathedral |

| Status | Active |

| Location | |

| Location | Bourges, France |

| Geographic coordinates | 47°04′55″N 2°23′58″E / 47.08194°N 2.39944°E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Church |

| Style | High Gothic, Romanesque |

| Groundbreaking | 1195 |

| Completed | c. 1230 |

| Official name: Bourges Cathedral | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iv |

| Designated | 1992, modified 2013 |

| Reference no. | 635bis |

| State Party | France |

| Region | Europe and North America |

| Session | 16th |

Bourges Cathedral (French: Cathédrale Saint-Étienne de Bourges) is a Roman Catholic church located in Bourges, France. The cathedral is dedicated to Saint Stephen and is the seat of the Archbishop of Bourges. Built atop an earlier Romanesque church from 1195 until 1230, it is largely in the Classic Gothic architectural style and was constructed at about the same time as Chartres Cathedral. The cathedral is particularly known for the great size and unity of its interior, the sculptural decoration of its portals, and the large collection of 13th century stained glass windows.[1] Owing to its quintessential Gothic architecture, the cathedral was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1992.[2]

History

Earlier cathedrals

The walled city of Avaricum, the capital of the Gallic tribe of the Bituriges, was conquered by Julius Caesar in 54 B.C. and became the capital of the Gallo-Roman province of Aquitaine.[3] Christianity was brought by Saint Ursinus of Bourges in about 300 A.D.; He is considered the first Bishop. A "magnificent" church building is mentioned by Gregory of Tours in the 6th century. In the 9th century, Raoul de Turenne reconstructed the older building. Between 1013 and 1030 a new and larger cathedral was constructed by the Bishop Gauzelin. Like the earlier churches, it was built against the city wall, and vestiges of it can be found under the present cathedral.[3]

In about 1100, King Philip I of France added Bourges and its province to his growing kingdom.[3] In 1145 his son Louis VII of France presented his new wife Eleanor of Aquitaine, and she was formally crowned Queen of France in the old Gothic cathedral in Bourges. Beginning in about 1150 the Archbishop Pierre de La Châtre enlarged the old cathedral by adding two new collateral aisles, one on either side, each with two Romanesque portals, and also planned the reconstruction of the west front.[3]

The Gothic cathedral (12th–13th century)

Under a new archbishop, Henri de Sully, a more ambitious building program began. In 1181–82 King Philip Augustus II authorised construction over parts of old ramparts overlooking the city. A document from the Bishop, Henry de Sully, indicated the total reconstruction of the cathedral in 1195. [4] The first work involved building a lower church in a space six meters deep where the old ramparts had been. This structure, with a double disambulatory, was finished in about 1200. It served as the base for the next portion, the chevet or east end, which was finished in about 1206. The work then preceded toward the west, from the apse to the choir.[4]

The cathedral was begun at about the same time as Chartres Cathedral, but the basic plan was very different. Whereas at Chartres and other High Gothic cathedrals the two collateral aisles were the same height as the nave, at Bourges the collateral aisles were of different heights, rising in steps from the outside aisle to the centre. The old nave was preserved for a time to allow worship until the new choir was finished in about 1214. Then work began on the five vessels, or aisles of the new nave. The cathedral was complete enough by 1225 to be able to host a large council condemning the heresy of Catharism. Major work on the nave was finished by 1235, with the installation of the rood screen, which separated the choir from the nave.

The next step was the building of the wooden framework for the roof, over the vaulted ceiling. This lasted from 1140 to 1155, and required the wood from nine hundred oak trees. The roofing continued until 1259, when a fire caused serious damage. Construction of the south tower was halted, probably out of caution, and work also stopped on the north tower.[4]

14th–16th century

Bourges Cathedral (background) depicted in the 15th century

Bourges Cathedral (background) depicted in the 15th century Interior of Bourges Cathedral, depicted in the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (15th century)

Interior of Bourges Cathedral, depicted in the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (15th century) The west portals depicted in the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (15th century)

The west portals depicted in the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (15th century)

Work on the facade continued in 1314 with the construction of a large bay, the Grand Housteau. A tall wooden spire was added to the cathedral, and the walls were strengthened with additional arched buttresses. Between 1406 and 1491, eleven new chapels were built along the flanks of the cathedral between the buttresses. These were lavishly decorated in the more ornate late Gothic style, somewhat out of harmony with the classical High Gothic of the earlier structure.[4]

In 1424 the cathedral was furnished with a technological novelty, the Bourges astronomical clock, still functional after many repairs. The long-troubled north tower was finally finished, but its foundations were still faulty. It collapsed on December 31, 1506. To raise funds for its reconstruction, Archbishop Guillaume de Cambrai offered dispensations to eat butter during Lent in exchange for contributions to the tower fund. The tower was repaired between 1508 and 1524, and thereafter was nicknamed the Butter Tower.[5]

After the 1506 tower collapse, the upper central portion of the west front, above the central portals, known as the Grand Housteau, was reconstructed in the Flamboyant Gothic style. The rebuilt front featured a group of six large lancet windows and two oculi beneath an immense rose window, surmounted by a pointed gable with a small rose blind rose window. Because of the stability problems, the new front and the towers were reinforced by massive buttresses.[6]

The old spire was removed in 1539 and replaced by a new one in 1543–44. In 1549 a fire in the beams of the roof of the north collateral aisles damaged the windows below, and also destroyed the organ. This time King Henry II of France paid for the repairs. The French Wars of Religion caused more serious damage. A Protestant army led by Gabriel de Lorges, the Count of Montmorency, seized the city by surprise on 27 May 1562. They pillaged the cathedral treasury, overturned statues and smashed some of the bas-relief sculpture. De Lorges was preparing to blow up the cathedral when he was dissuaded by others who wanted to convert it into a Protestant church.[7]

17th–18th century

A new organ was installed in the cathedral in 1667, portions of which still are in use. The fleche of the cathedral, rebuilt four times, was finally removed in 1745. In the 18th century, the entire cathedral underwent a more serious transformation, to conform with new doctrines instituted by the Vatican. The Gothic altar from 1526 and the elaborate sculpted stone rood screen of the choir from the 13th century were removed. Portions of the rood screen are displayed today in the crypt. Many of the stained glass windows were replaced with white grisaille glass to provide more light. A new choir screen composed of nine wrought iron grills was put in place in 1760. and a new altar of white marble was installed 1767. The choir also received new carved choir stalls and a new marble floor.[8]

During the French Revolution, the cathedral was transformed for a time into a Temple of Reason. Many of the reliquaries and other precious objects in the treasury were melted down for their gold, while ten of the twelve church bells were melted down to be reforged into cannon.[8]

Following the destruction of much of the Ducal Palace and its chapel during the revolution, the tomb effigy of Duke Jean de Berry was relocated to the cathedral's crypt, along with some stained glass panels showing standing prophets, which were designed for the chapel by André Beauneveu.

19th–21st century

In the 19th century, the cathedral was returned to the Catholic Church and underwent a long restoration from 1829 until 1847. The new architects made numerous modifications and additions which sometimes had a questionable historic basis. The buttresses and arches were decorated with pinnacles and new balustrades which may not have previously existed.

In 1862, under Emperor Louis Napoleon, the cathedral was declared an historic monument.

In 1992, the cathedral was added to the list of the World Heritage Sites by UNESCO.

In 1994–95, the rood screen of the lower church was restored, and the astronomical clock was put back into working order. The old stained glass windows were cleaned and protected by additional layers of glass. The murals in the chapel of St. John the Baptist were restored.

Timeline

- c. 300 – According to tradition, Christianity first established in Bourges[9]

- c. 500 – First cathedral buildings on the site.

- 844–866 – Bishop Raoul de Touraine reconstructs the cathedral in Carolingian style

- 1013–1030 – Bishop Gauzelin rebuilds the cathedral, of which parts of the crypt still exist[9]

- c. 1100 – King Philip I of France acquires the Vicomté of Bourges for France

- 1137 – Louis VII crowned in the cathedral

- 1145 – Eleanor of Aquitaine presented as Queen

- 1195 – Archbishop Henri de Sully collects funding for a new cathedral in the Gothic style. Work begins.

- c. 1206 – Lower level of choir completed.

- c. 1214 – Choir substantially completed.

- c. 1230–1235 – Nave and first levels of west front complete.

- 1255–59 – Wooden roof framework and vaults of the nave completed.

- 1313–1314 – Construction of the support pillar and the Grand Housteau window on west front

- 1324 – Dedication of cathedral by Archbishop Guillaume de Brosse[3]

- 1424 – Installation of Astronomical clock

- 1493–1506 -North tower completed, but collapses in 1506. Rebuilt by 1515.

- 1562 – Cathedral pillaged by Protestants in European Wars of Religion[3]

- 1667 – Installation of new grand organ

- 1750–1767 – Removal of medieval choir stalls and decoration, replaced by Baroque and French Classical decor

- 1791 – During French Revolution, destruction of choir decoration and furniture and cathedral bells. Treasury confiscated.[3]

- 1829–47 – First restoration of west front portal sculpture

- 1845–47 – Restoration of stained glass of the choir and disambulatory.

- 1846–78 – Restoration of chapel and the lateral portals

- 1882 – Repair of upper walls and windows

- 1992 – Cathedral declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site

- 1994–95 – Astronomical clock put back in working order. Old stained glass cleaned and protected with double panes.[3]

- 2001–2018 – Restoration of portals, coverings, supporting pillar and the Chapel of Étampes.

Exterior

Façade or west front

The façade or west front, the main entrance to the cathedral, is on a particularly grand scale when compared with other cathedrals of the period; it has five portals accessing the central aisle and four side aisles, more than Notre Dame de Paris or any other cathedral of the period.

West Façade Portals

Sculpture illustrating the Day of Judgement in the tympanum over the central portal

Sculpture illustrating the Day of Judgement in the tympanum over the central portal The punishment of sinners depicted on the tympanum of the central portal

The punishment of sinners depicted on the tympanum of the central portal_Cath%C3%A9drale_Saint-%C3%89tienne_-_Ext%C3%A9rieur_-_Portail_Saint-%C3%89tienne_-_03.jpg.webp) The stoning of Saint Stephen ([portal right of center)

The stoning of Saint Stephen ([portal right of center)_Cath%C3%A9drale_Saint-%C3%89tienne_-_Ext%C3%A9rieur_-_Portail_Saint-Guillaume_-_02.jpg.webp) The portal of Saint Guillaume depicts the spire of the cathedral, since disappeared

The portal of Saint Guillaume depicts the spire of the cathedral, since disappeared_Cath%C3%A9drale_Saint-%C3%89tienne_-_Ext%C3%A9rieur_-_Portail_Saint-%C3%89tienne_-_19.jpg.webp) Angels in the portal of Saint Stephen

Angels in the portal of Saint Stephen_Cath%C3%A9drale_Saint-%C3%89tienne_-_Ext%C3%A9rieur_-_Portail_Saint-%C3%89tienne_-_08.jpg.webp) arch of Lower arcade in the portal of Saint Stephen (13th c.)

arch of Lower arcade in the portal of Saint Stephen (13th c.)

The sculpture on the central portal illustrates scenes from Last Judgement. At the top of the tympanum, Christ divides the damned from the saved. Their respective fates are vividly illustrated below. The original sculptures were badly damaged in the sixteenth century during the Wars of Religion. Parts of the tympanum were restored by Théophile Caudron in the nineteenth century.[10]

The portal to the near right of the center depicts the life of Saint Stephen, the patron saint of the cathedral. The sculptures on the portal above the far-right door depict scenes from the life of St Ursinus, a local saint and the first bishop of the diocese. The scenes are read from bottom to top and from right to left. They include a depiction of Ursinus consecrating the cathedral (center) and the baptism of the Roman senator Leocadus and his son Ludre (top). The trumeau statue depicting St. Ursinus was made by Caudron in 1845 after the original was destroyed.[11]

The original tympana of the north portals were destroyed when the north tower collapsed in 1506 and were redone in the sixteenth century in a somewhat different style. The tympanum to the near-left portal shows scenes from the life of the Virgin Mary. The lower portion of this portal, up to the trumeau date to the sixteenth century.[12] The far left tympanum is dedicated to William of Donjeon, and depicts scenes from his life. The portal is topped with an openwork gable and is divided in the center by a richly ornamented spire. The archivolts above the portal depict angels, many of whom are shown playing musical instruments.[13]

The lower arcade contain a collection of sixty four bas-relief sculptures depicting examples of divine intervention drawn from commentaries on the Bible in the Talmud. They were carved in the thirteenth century and their unique iconography was possibly designed by a member of Bourges's large Jewish community.[13][14]

The spandrels between these niches feature an extended Genesis cycle which would originally have told the story from the beginning of Creation to God's Covenant with Noah.[15] The spandrels were defaced in 1562.[16]

Romanesque carved portals from about 1160–70, probably intended for the façade of the earlier cathedral, have been reused on the south and north doors (occupying the spaces normally reserved for transept portals). Their profuse ornamentation is reminiscent of Burgundian work.

Towers and the Grand Housteau

Top of the north tower, with its flamboyant decoration and bronze pelican

Top of the north tower, with its flamboyant decoration and bronze pelican.jpg.webp) The flamboyant Grand Housteau and west rose window

The flamboyant Grand Housteau and west rose window The bell of the Duke Jean and the bronze pelican on the north tower

The bell of the Duke Jean and the bronze pelican on the north tower

The north tower is the only one finished and is the taller of the two. It was given an elaborate Flamboyant Gothic decoration including a profusion of ornamental pinnacles and crockets, as well as copies of 13th-century statues installed in the niches. At the top is a lantern crowned by a large bronze pelican. The original 16th-century pelican statue is kept inside the cathedral. This tower contains the six bells of the cathedral, which replaced those melted down during the Revolution. They date to the 19th and 20th century. The largest is the bourdon, Guillaume-Etienne of Gros Guillaume, 2.13 meters in diameter and weighing 6.08 tons. It was cast in 1841–42.[17]

The south tower, the shorter of the two and unfinished, had insufficient foundations and was unstable from the beginning. It was eventually reinforced in 1314 with a massive buttress on its flank. This buttress, besides supporting the tower, contained a stairway and the small prison operated by the cathedral chapter. The upper room of the buttress was used as the office of the architect, and has plans of the bays and a rose window etched on the stone floor, where they could be consulted by cathedral builders. In the 18th century, it was used for a time as a studio by the painter François Boucher.[17]

The south tower originally contained the belfry and the great bells of the cathedral. These were removed following the Revolution and melted down for their bronze. As a result, the tower was called "Le Sourde" ("the deaf") or "Le Muette" ("The silent").[17]

The central portion of the west front above the portals and between the towers is known as the Grand Housteau. It is later than the rest of the west front, rebuilt in the 16th century in the Flamboyant Gothic style, following the collapse of the north tower. The exceptional height of the Grand Housteau and its rose window announces the great height of the nave behind it.[6]

North and south sides

The north and south walls are lined with the flying buttresses which reach up over the lower aisles to support the upper walls. and which make possible the large upper windows. They are given additional weight by heavy pinnacles. Small chapels were constructed between a number of the buttresses in later centuries, but in those bays without chapels, the walls of the old Romanesque cathedral are still visible.[18]

Unlike most other High Gothic cathedrals, Bourges does not have a transept, but there is a porch and portal on the south side which originally was used only by the clergy. It contains vestiges of the older Romanesque church, particularly six column-statues which date to about 1150–60, which were put in place under the porch in the 13th century as a reminder of the long history of the cathedral. Traces of paint show that the sculptures were once brightly colored. Some of the sculpture is inscribed with the heart and letter J emblem of the family of Jacques Coeur, prominent Bourges merchants and major donors to the cathedral. Their tombs are inside the cathedral.[18]

South side of the cathedral and south porch

South side of the cathedral and south porch Sculture of south porch tympanum

Sculture of south porch tympanum Sculpture of the south porch

Sculpture of the south porch Column-statue and tympanum of the south porch

Column-statue and tympanum of the south porch

The north side, facing the city, has a similar plan. Many of the spaces between the buttresses have been filled with chapels. There is porch midway along the north side for access by the ordinary members of the parish. Like the south porch, the portals of the north porch are decorated with column statues and other sculptures dating back to the Romanesque cathedral. The column statues apparently represent the Queen of Sheba and a Sibyl, while the sculpture in arches above the portals represent a Virgin and child. Miniature architectural scenes have images of the Biblical Magi, an Annunciation and a Visitation scene, illustrating the Biblical account of Mary. Some of the sculpture on this porch was defaced in the French Wars of Religion.

Over the north doorway is a round window without glass decorated with sculptures of heads of mythical beasts. The roof over the north portal suffered from a fire in 1559 and was replaced by an iron roof. The entire portal is lavishly decorated with elaborate vegetal and geometric sculpture.[19]

The sacristy of the cathedral, next to the porch, also juts out from the north side. It was donated by the merchant Jacques Coeur.

.jpg.webp) The north portal porch

The north portal porch Sculpture of Virgin Mary and child on north portal

Sculpture of Virgin Mary and child on north portal.jpg.webp) North portal doorway

North portal doorway North portal column statue and decoration

North portal column statue and decoration

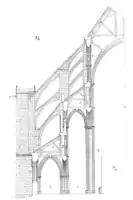

The Chevet

The Chevet is the French term for the exterior of the apse, the east end of the cathedral, with its ring of radiating chapels. The chevet of Bourges is different from the other High Gothic cathedrals, since the lower aisles have different elevations, and the chevet rises upwards in three steps, with the upper walls supported by six converging buttresses that leap over the lower levels. with separate arches supporting the lower and upper walls. The verticality is enhanced further by the pointed roofs of the radiating chapels, the double pinnacles on each buttress, and the pinnacles around the balustrade of the roof. Each bay of the high walls is decorated with twin lancet windows and a small six-lobe rose window, framed in blind arches.[20]

Radiating chapels of the chevet of Bourges Cathedral

Radiating chapels of the chevet of Bourges Cathedral The chevet – side view

The chevet – side view

Interior

Plan and elevation

Plan, with four collateral aisles

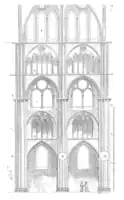

Plan, with four collateral aisles Elevation, drawn by Viollet-le-Duc

Elevation, drawn by Viollet-le-Duc Cross section, showing aisles of different heights

Cross section, showing aisles of different heights

Bourges Cathedral covers a surface of 6,200 square metres (7,400 sq yd). The cathedral's nave is 41 metres (135 ft) wide by 37 metres (121 ft) high; its arcade is 20 metres (66 ft) high; the inner aisle is 21.3 metres (70 ft) and the outer aisle is 8.6 metres (28 ft) high.[21]

The interior is 118 metres (387 ft) long from the west front to the chevet. Sexpartite vaults are used to span the nave.

The height of the nave from the floor to the vaults is 37.15 metres (121.9 ft) compared with 33 metres (108 ft) at Notre Dame de Paris, 42 metres (138 ft) at Amiens Cathedral, and 48 metres (157 ft) at Beauvais Cathedral.

Bourges Cathedral is notable for the simplicity of its plan, which did without transepts but which adopted the double-aisled design found in earlier churches such as the Early-Christian basilica of St Peter's in Rome or in Notre Dame de Paris. The double aisles continue without interruption beyond the position of the screen (now largely destroyed though a few fragments are preserved in the crypt) to form a double ambulatory around the choir. The inner aisle has a higher vault than the outer one, while both the central nave and the inner aisle have similar three-part elevations with arcade, triforium and clerestory windows; a design which admits considerably more light than one finds in more conventional double-aisled buildings like Notre-Dame.[22] This design, with its distinctive triangular cross-section, was subsequently copied at Toledo Cathedral and in the choir at Le Mans.[23]

Nave and choir

The central vessel of the nave and choir, looking east

The central vessel of the nave and choir, looking east The lower collateral aisles

The lower collateral aisles The alternating pillars of the nave. The collateral aisles are in the background.

The alternating pillars of the nave. The collateral aisles are in the background. 18th=century altar and apse at the east end

18th=century altar and apse at the east end Windows of the disambulatory of the east end

Windows of the disambulatory of the east end

The nave, between the west end and the choir, where ordinary worshippers were seated, occupied the majority of the interior. The choir, the area reserved for the clergy, occupied the four traverses before the east end. The east end, or apse, gave access to a hemicycle of five radiating chapels.

Bourges Cathedral is noted for its immense and unified interior space; there is no interruption in the interior between the west front and the chevet on the east. The pillars of the arcade are 21 meters high, more than half of the 37 meters of height up to the vaults. Each pillar is composed of a central column, two of which are attached to the slender colonettes which spread out at the top and connect to the rib vaults. The first two pillars of the first crossing at the west are of particularly large size. each with twenty-one colonettes. The successive pillars to the west alternate between the thicker "strong" pillars with five colonettes and "weak" pillars" with four, depending upon their position supporting the vaults overhead.[24]

The central vessel of the nave has three levels; the very high arcade on the ground level; the triforium, a narrow arcade, above it; and, at the top, the upper bays, largely filled with windows. Each of the six-part rib vaults covers two traverses. The walls of the collateral aisles are not as tall, though they also have windows in each bay, and rib vaults supported by slender columns.[24]

In the Middle Ages, the choir was used exclusively by the clergy and was separated from the nave by a decorated rood screen or ornamental barrier. Portions of the old screen are displayed in the crypt. A decorative Neo-Gothic wrought-iron screen, installed in 1855, now surrounds the choir.

The pillars of the choir are slightly thinner than those of the nave, but they blend harmoniously with the rest of the interior. At the top level, the high windows with their circular oculi are fit into the peaks of the arches, adding to the sensation of uninterrupted height. The upper choir ends with a curving hemicycle of windows.[24]

The choir was substantially remodelled in the 18th century to conform with new doctrines from the Vatican, calling for richer Baroque decoration. These changes included new carved choir stalls made by René-Michel Slodtz, marble pavement in a checkerboard pattern, and a new main altar designed by Louis Vassé, formally consecrated in 1767.[24]

Chapels

.jpg.webp) Painting in the Chapel of Saint Stephen

Painting in the Chapel of Saint Stephen.jpg.webp) The Chapel of St. John the Baptist, mural of Christ resurrected and Mary Madeleine (1467–79)

The Chapel of St. John the Baptist, mural of Christ resurrected and Mary Madeleine (1467–79)

The cathedral is ringed with chapels constructed over the centuries, inserted into the spaces between the buttresses on the flanks, and radiating in a half-circle around the chevet. There are five chapels in the apse, six lining the disambulatory, or outer aisle on the east end, six on the south side, and four on the north side. Some contain tombs, and they generally honour specific donors or saints. One of the most lavish chapels, The Chapel of St. John the Baptist, was constructed between 1467 and 1479 in the disambulatory of the north side. It was funded by Jean de Breuil, archdeacon of the cathedral and a counsellor of the Parliament of Paris. It contains a rich assortment of murals and very fine 15th century stained glass. All the architecture is painted, gilded and decorated.[24]

The Chapel of Saint Anne, on the south side of the disambulatory, was donated by one of the wealthy members of the Chapter, Pierre Tullier. The stained glass depicted the family of the donor being presented to the Saint. It was made by the master glassmaker Jean Lécuyer in 1532.[25]

The most poignant chapel is that of Jacques Coeur, one of the major donors to the cathedral. It is located on the outer disambulatory on the north side, and was built in 1448 to contain Coeur's tomb. The remarkable window, one of the finest works of 15th-century stained glass, was made in 1453. It depicts the Archangel Gabriel informing Mary that she would be the mother of Christ. In the same year the window was made, Jacques Coeur was arrested for misappropriation of funds. The family was forced to sell his residence and his burial rights in the chapel to another wealthy noble, Charles de L'Aubespine. Aubespine commissioned the architect François Mansart to design the tomb for the new owner. Pieces of sculpture from that tomb are presented in the chapel.[26]

Head of Jeanne de Boulogne in the Chapel of Notre Dame La Blanche (1403)

Head of Jeanne de Boulogne in the Chapel of Notre Dame La Blanche (1403) Head of Jean de Berry in the Chapel of Notre Dame La Blanche (1403)

Head of Jean de Berry in the Chapel of Notre Dame La Blanche (1403)

Fine examples of 15th-century sculpture are found in the Chapel of Notre-Dame La Blanche, in the centre of the apse at the east end of the cathedral. These include busts of the Duke Jean de Berry, whose tomb in the lower church, and that of his wife Jeanne be Boulogne, were made by Jean de Cambrai in about 1403 They were moved to the cathedral from the Sainte-Chapelle chapel in Bourges in 1757. The heads and hands were smashed during the Revolution, but were restored in 19th century.[26]

Lower church and the tomb of the Duke of Berry

The lower church was constructed first atop the old ramparts to level a steep slope of six meters and to serve as a foundation for the chevet and the last first traverse of the upper church. It was completed in about 1200. Its arched ceiling is supported by massive pillars and seven arcades, and a wall three meters thick pierced with lancet windows. At one time it apparently served as the master builder's office; the plans of the rose window on the west pignon are etched onto the floor. scratched onto the floor.[27] Today it has a collection of stained glass made between 1391 and 1397 which formerly was installed in the windows of the Sainte-Chapelle chapel constructed by John, Duke of Berry, which was destroyed in 1757.

The Duke was an important art collector of the era; among the works he commissioned was the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. The tomb itself is one of the major art works in the chapel. It was made between 1391 and 1397 and is an important work of medieval sculpture, made between 1422 and 1428 by the sculptor Jean de Cambrai. The ensemble of sculpture includes the marble tomb of the Duke, with his symbolic animal, a bear chained and muzzled, at his feet. Nearby are statues of the Duke and Jeanne of Boulogne, both remakes attributed to the sculptor Jean Cox in about 1710. The tomb originally featured a collection of forty sculpted mourners, made of marble and alabaster. These have now been largely scattered to different museums.[27]

Other objects of interest in the lower church include pieces of sculpture the original Jubé, or Rood screen, made in Paris in the 1230s, which divided the choir from the nave until the 18th century. The screen was badly damaged in 1562 during the Wars of Religion, and then destroyed in 1757 during the reconstruction of the choir. The display includes recreations and original pieces.

.jpg.webp) Painting in the Chapel of Saint Stephen

Painting in the Chapel of Saint Stephen.jpg.webp) The Chapel of St. John the Baptist, mural of Christ resurrected and Mary Madeleine (1467–79)

The Chapel of St. John the Baptist, mural of Christ resurrected and Mary Madeleine (1467–79) Tomb of John, Duke of Berry in the lower church

Tomb of John, Duke of Berry in the lower church Sculpture of those condemned to hell from the original rood screen (1230s)

Sculpture of those condemned to hell from the original rood screen (1230s)

Organ

The original organ of the cathedral was below the rose window on the inside the west front. It was destroyed in 1506 by the collapse of the neighbouring tower. Some of the sculptural decoration near its former position, portraying angel musicians and caryatides, recalls its presence. It was replaced with a new instrument beginning in 1663. the buffet of the organ was made in 1665 by Bernard Perette. The organ was modified and enlarged in 1741 and 1860, and given a modern renovation in 1985.

The present organ has fifty stops or particularly sounds, more than 2500 pipes, four keyboards, and a set of pedals for playing additional notes.[28]

Astronomical clock

The astronomical clock of Bourges Cathedral was first installed in November 1424, during the reign of Charles VII, when the royal court was based in Bourges, for the occasion of the baptism of his son the Dauphin (the future Louis XI). Designed by the canon and mathematician Jean Fusoris and constructed by André Cassart, the clock is housed in a belfry-shaped case painted by Jean Grangier (or Jean of Orléans). It has two dials, the upper one added in the 19th century showing the time, the lower one showing the hour, the moon phase and age, and the position of the sun in the zodiac.

The clock's bells chime on the quarter-hour and chime the first four notes of the Salve Regina on the hour. The clock on the top displays the minutes and hours with great precision, with a margin of error of one second per one-hundred-fifty years. The lower face displays the prominent constellation in the night sky, the phase of the moon and the sign of the zodiac.[29]

The clock was restored in 1782, 1822, 1841, and completely overhauled in 1872, when the upper dial showing only the time was installed. The zodiac calendar was restored in 1973. The clock was badly damaged by fire in 1986; after a complete restoration, the clock was reinstalled in 1994 with a replica mechanism. The original mechanism is on display in the cathedral.

.jpg.webp) The lower face of the clock

The lower face of the clock.jpg.webp) The restored astronomical clock (15th century)

The restored astronomical clock (15th century).jpg.webp) Original mechanism of the clock

Original mechanism of the clock

Stained glass

Bourges Cathedral is especially noted for its 13th-century stained glass, particularly the windows in the chapels of the ambulatory of the apse, which date from around 1215, about the same time the windows of Chartres Cathedral (The windows in the axial chapel at the end of the apse are more recent). The famous windows at Bourges are mostly on the ground level, giving a better opportunity than most Gothic cathedrals offer to examine them closely.[30] (See gallery at end of article for full windows)

Grand Housteau and apse

The west front has a blind rose window on the arch over the central portals; a large window with six lancets and two oculi above that, beneath a large rose window; and another smaller rose in the pointed arch above. The rose window of the Grand Housteau dates to about 1392. It has geometric designs surrounding a window of a dove representing the Holy Spirit. The exterior of the facade, called the Grand Housteau, is in the Flamboyant style, and dates to the early 16th century.[31]

The high windows of the apse, at the east end, form a half-circle, with two windows topped by an oculus in each bay. The central window depicts the Virgin Mary holding the Infant Saint Stephen, holding a model of the cathedral. On the north side, the upper windows depict nineteen prophets in chronological order, beginning with John the Baptist on the east side of the Virgin. On the south side, to the west of the Virgin, are nineteen windows depicting apostles and disciples.[32]

Rose window on the west front

Rose window on the west front High windows of the apse

High windows of the apse

Windows of the apse ambulatory (13th century)

One of the best-known windows from this period is the Joseph window, in the ambulatory to the right of the Chapel of Saint Francis of Sales. Its medallions depict events in the life of Joseph, the son of Jacob, as he searches for his brothers. It also depicts barrel-makers and carpenters at work; these two guilds were the patrons of the window. The window depicting the Parable of Lazarus and Rich Man and Lazarus depicts stonemasons, whose guild funded that window.[30]

The ambulatory includes several other Typological window (similar to examples at Sens Cathedral and Canterbury Cathedral), and several hagiographic cycles, the story of the Old Testament patriarch, Joseph and symbolic depictions of the Apocalypse and Last Judgement. Other windows show the Passion and three of Christ's parables; the Good Samaritan, the Prodigal Son and the story of Dives and Lazarus. The French art historian Louis Grodecki identified three distinct masters or workshops involved in the glazing, one of whom may also have worked on the windows of Poitiers Cathedral.[33]

Scenes from the life of Joseph searching for his sons, and also barrel-makers and carpenters at work

Scenes from the life of Joseph searching for his sons, and also barrel-makers and carpenters at work Detail of the window of the Last Judgement; sinners punished

Detail of the window of the Last Judgement; sinners punished Scene from window of the Passion – The Last Supper.

Scene from window of the Passion – The Last Supper. Scene from the parable of Lazarus and the Bad Rich; stonemasons at work (Apse)

Scene from the parable of Lazarus and the Bad Rich; stonemasons at work (Apse) Detail of the Apocalypse Window (apse)

Detail of the Apocalypse Window (apse)

Stained Glass Legendary Windows in the Disambulatory (13th century)

Life of John the Baptist

Life of John the Baptist The Passion of Christ

The Passion of Christ Parable of the Good Samaritan

Parable of the Good Samaritan Life of Patriarch Joseph

Life of Patriarch Joseph Legend of Saint Thomas

Legend of Saint Thomas Life of Saint James the Great

Life of Saint James the Great The New Alliance

The New Alliance The Apocalypse

The Apocalypse Invention of the relics of Saint Stephen

Invention of the relics of Saint Stephen

Windows of the nave and choir

Nearly all of the upper windows of the nave and the collateral aisle are filled with grayish grisaille glass, to provide maximum light. Only the small rose windows above them have figures, largely combinations of sainted bishops and cardinals. The first five small roses to the east of the facade in the inner collateral aisle depict the Old Men of the Apocalypse, some playing musical instruments, including a kind of accordion, a very early depiction of that instrument.[34]

15th- and 16th-century stained glass

A number of windows from the 15th and 16th centuries are found in the chapels. They show the Renaissance influence, much closer to paintings than earlier windows, with greater realism and the use of perspective. One of the best examples is the Annunciation Window, located in the Chapel of Jacques Coeur. It was originally in the Sainte Chapelle of Bourges, which was destroyed during the Revolution.[34]

The Chapel of Saint Joan of Arc was constructed in 1468 and has a notable 16th-century window devoted to the life of Joan of Arc in sixteen scenes, with precise Renaissance detail and colouring. It was installed in 1517.[35]

The chapels along the collateral aisles also contain some remarkable 15th-century windows. The Chapel of Notre Dame de Sales, or Chapel of the King, on the south side of the nave near the west front, features a window presenting the twelve apostles beneath elaborate architectural settings (1473–74).

The axial Chapel of Notre-Dame-la-Blanche, at the east end of the apse, also has a set of 16th century which were originally in the Sainte-Chapelle chapel of in Bourges. The main window presents scenes of the Assumption of the Virgin.

Window of the Apostles (15th century)

Window of the Apostles (15th century) Chapel of Saint Joan of Arc, Scenes from the life of Saint Denis (15th century) (click to enlarge)

Chapel of Saint Joan of Arc, Scenes from the life of Saint Denis (15th century) (click to enlarge) Chapel of Jacques Coeur, The Announciation (1448–1450)

Chapel of Jacques Coeur, The Announciation (1448–1450) Windows of the Chapel of Saint Joseph, or Alligret (1415)

Windows of the Chapel of Saint Joseph, or Alligret (1415) Chapel of De Breuil - Adoration of the Magi (1467–79)

Chapel of De Breuil - Adoration of the Magi (1467–79) Chapel of Beaucaire - Doctors of the Church (1452)

Chapel of Beaucaire - Doctors of the Church (1452) Chapel of Saint Anne, or Tullier (1533); the Tullier family is presented to Saint Anne

Chapel of Saint Anne, or Tullier (1533); the Tullier family is presented to Saint Anne Assumption of the Virgin window, Axial chapel (16th century)

Assumption of the Virgin window, Axial chapel (16th century) Details of the Assumption of the Virgin, Axial chapel (16th century) (click 3X to enlarge)

Details of the Assumption of the Virgin, Axial chapel (16th century) (click 3X to enlarge) The Coppin Chapel, south collateral, (1518)

The Coppin Chapel, south collateral, (1518)

See also

Notes and citations

- ↑ Villes 2018, p. 3.

- ↑ "Bourges Cathedral". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Villes 2018, p. 7.

- 1 2 3 4 Villes 2018, p. 11.

- ↑ Villes 2018, p. 15.

- 1 2 Villes 2018, p. 25.

- ↑ Villes 2018, p. 17.

- 1 2 Villes 2018, p. 19.

- 1 2 Villes 2018, p. 94.

- ↑ Villes 2018, p. 28.

- ↑ Villes 2018, p. 30-31.

- ↑ Villes 2018, p. 32.

- 1 2 Villes 2018, p. 32–33.

- ↑ Jennings 2011, p. 1-10.

- ↑ Bayard, Tania, Thirteenth-Century Modifications in the West Portals of Bourges Cathedral, in Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 34, No. 3 (Oct., 1975), pp. 215–225

- ↑ Villes 2018, p. 33.

- 1 2 3 Villes 2018, p. 37.

- 1 2 Villes 2018, p. 38–39.

- ↑ Villes 2018, p. 42–43.

- ↑ Villes 2018, p. 40–41.

- ↑ Villes 2018, p. inside cover.

- ↑ Branner, Robert, The Cathedral of Bourges and its Place in Gothic Architecture, Paris (1962)

- ↑ Bony, Jean (1985). French Gothic Architecture of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries, p. 212. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05586-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Villes 2018, p. 46–47.

- ↑ Villes 2018, p. 58–59.

- 1 2 Villes 2018, p. 69.

- 1 2 Villes 2018, p. 89.

- ↑ Villes 2018, p. 48.

- ↑ Villes 2018, p. 49.

- 1 2 Villes 2018, p. 62.

- ↑ Villes 2018, p. 50.

- ↑ Villes 2018, p. 52.

- ↑ Louis Grodecki. A Stained Glass Atelier of the Thirteenth Century: A Study of Windows in the Cathedrals of Bourges, Chartres and Poitiers, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 11, (1948), pp. 87–111

- 1 2 Villes 2018, p. 90.

- ↑ Villes 2018, p. 84.

Bibliography

- Bony, Jean (1985). French Gothic Architecture of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05586-1.

- Villes, Alain (2018). Cathédrale Saint-Étienne Bourges. Éditions du Patrimoine, Centre des Monuments Nationaux. ISBN 978-2-7577-0559-9.

- Jennings, Margaret (2011). "The Cathedral of Bourges: A Witness to Jude-Christian Dialogue in Medieval Berry". Studies in Christian-Jewish Relations. 6: 1–10. doi:10.6017/scjr.v6i1.1584. Retrieved 13 May 2022.