| Château de Vincennes | |

|---|---|

| Part of Vincennes | |

| Île-de-France | |

Donjon of the Château de Vincennes | |

Château de Vincennes | |

| Coordinates | 48°50′34″N 2°26′09″E / 48.84278°N 2.43583°E |

| Type | Medieval castle |

| Site information | |

| Website | www |

| Site history | |

| Built | c. 1340–1410 |

| Built by | Charles V of France |

| Events | |

The Château de Vincennes (French pronunciation: [ʃɑto d(ə) vɛ̃sɛn]) is a former fortress and royal residence next to the town of Vincennes, on the eastern edge of Paris, alongside the Bois de Vincennes. It was largely built between 1361 and 1369, and was a preferred residence, after the Palais de la Cité, of French Kings in the 14th to 16th century. It is particularly known for its "donjon" or keep, a fortified central tower, the tallest in Europe, built in the 14th century, and for the chapel, Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes, begun in 1379 but not completed until 1552, which is an exceptional example of Flamboyant Gothic architecture. Because of its fortifications, the château was often used as a royal sanctuary in times of trouble, and later as a prison and military headquarters. The chapel was listed as an historic monument in 1853, and the keep was listed in 1913. Most of the building is now open to the public.[2]

History

12th–14th century – Louis VII to Saint Louis

The first royal residence was created by an act of Louis VII in 1178. The site had the advantages of good hunting in the surrounding forest, proximity to two former Roman roads to Sens and to Lagny, as well as access by water on the Marne and Seine rivers. It was used only occasionally by Louis VII and his successors, but Louis IX, or Saint Louis (1226–1270), used it much more often, second only to his time at the Palais de la Cité in Paris. He held meetings of the royal council there, and the Queen and his children often resided there when he was absent from Paris.[3] When Louis IX purchased the reputed Crown of Thorns from the Emperor at Constantinople, Louis received the celebrated relic at Sens Cathedral, escorted it to Vincennes, and then accompanied it to its eventual home in the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris. A few thorns from the crown of thorns and a small fragment of the reputed True Cross were deposited at Vincennes for placement in a future chapel. Louis IX said farewell to his family at Vincennes before his departure to the Crusades, from which he did not return.[3]

The Chateau was frequented by the Kings and their families. Philippe III (in 1274) and Philippe IV (in 1284) were each married there and three 14th-century kings died at Vincennes: Louis X (1316), Philippe V (1322) and Charles IV (1328). The residence at the time was a sprawling manor with four wings located in the northeast corner of the present chateau walls, begun in the late 13th century. It was transferred to the clergy of the Saint-Chapelle after the Keep was completed; vestiges were found during excavations in 1992–1996.[4]

14th century – Fortress of Jean II and Charles V

The defeats of the French and the capture of the King by the English in the Hundred Years War, as well as uprisings of the Parisian merchants under Etienne Marcel (1357–58) and a rural upraising against the crown, the Jacquerie (1360), persuaded the new French King, Jean II of France and his son, the future Charles V, that they needed a more secure residence close to, but not in the center of Paris. The King ordered the construction of a fortress at Vincennes with high walls and towers surrounding a massive keep or central tower, 52 meters (172 feet) high. The work was started in about 1337, and by 1364 the three lower levels of the keep were finished. Charles V moved into the keep in 1367 or 1368, while construction was still underway. When it was completed in 1369–70, it was the tallest fortified structure in Europe. The digging of the deep moat came next (1367), then the fortified gateway (1369). The walls and towers surrounding the keep were finished in 1371–72.[4]

Late 14th – Late 15th century – Wars of Religion – Royal fortress and refuge – La Sainte Chapelle

_-_WGA13030.jpg.webp) The Chateau behind a boar hunt, by Limbourg Brothers or Barthélemy d'Eyck (1412–1416)

The Chateau behind a boar hunt, by Limbourg Brothers or Barthélemy d'Eyck (1412–1416) The Chateau by Jean Fouquet (1455)

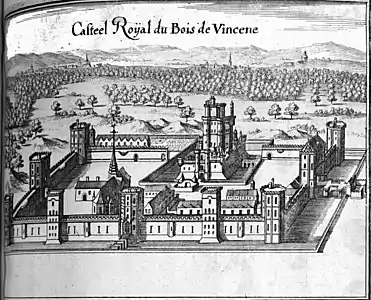

The Chateau by Jean Fouquet (1455) The Chateau of Charles V by Pierre Nicolas Ransonette (18th c. engraving), before the truncation of the perimeter towers.

The Chateau of Charles V by Pierre Nicolas Ransonette (18th c. engraving), before the truncation of the perimeter towers.

In the turbulent 15th century, the Chateau became a refuge for the kings of France. It was the regular residence of Charles VI of France up until his madness, then was disputed by the two rivals of his succession, Philip the Good of Burgundy and Louis I, Duke of Orléans. In 1415 the knights of Henry V of England defeated the French at the Battle of Agincourt. The Treaty of Troyes in 1420 granted the Chateau and the Ile-de-France to the English. Henry V of England installed his troops there, repaired the Chateau, and died there of dysentery in 1422, aged 35.[4]

An alliance between the Burgundians with Charles VII of France finally allowed the King to force the English out of the Ile-de-France and to reoccupy the Chateau. He and his successors rarely lived there, preferring the Loire Valley. His successor, Louis XI, also spent most of his time in the Loire Valley, but he made one major modification to Vincennes: He constructed a new royal residence within the walls, the first outside of the keep. It extended the entire length of the southeast wall.[5]

Charles V had even greater ambitions for the Chateau. At the end of 1372, he began construction of another wall, a large square more than a kilometre (0.6 mi) in length, with towers, to contain the additional buildings he intended to build. This was constructed between 1372 and 1385. The outer wall was given further reinforcement with the construction of a deep moat. The last project begun by Charles the V was laying the foundations of the Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes to hold a set of sacred relics obtained by Louis IX, but he died in 1380 in the Manoir de Beauté, a separate residence he had constructed in 1376–1377 southeast of Vincennes, when the work on the new Sainte-Chapelle had just begun.[4]

The Sainte-Chapelle of Vincennes, begun in 1379, was still unfinished in the 16th century. In 1520 King Francois I, a frequent resident, resolved to complete it to celebrate the birth of his son and heir. After his death in 1547, Henry II of France took up the work, finishing the vaults, and adding the woodwork and especially the stained glass. It was completed in 1552.[6]

17th and early 18th century – new royal residences

In the early 17th century, Marie De' Medici, the widow of the assassinated Henry IV of France, began a major project to replace the old pavilion of Louis XI and Francois I. Her son Louis XIII, then age ten, laid the first stone of the new residence in 1610. Louis XIV continued the program on an even larger scale; planned by the royal architect Louis Le Vau. his new residence in the French classical style, now the Batiment du Roi, was finished in 1658, and was twice the size of the Louis XIII residence. In 1688, work began on a new pavilion of the Queen, on the north side of the enclosure. A new formal garden with an orangerie, was built on the west side. A large group of painters and sculptors was assembled to decorate the new buildings. The ensemble was completed with a triumphal arch at the entrance, and was dedicated in August 1660, in time for the return of the King and his new bride to Paris. But the age of royal glory at Vincennes was brief; in 1682 Louis XIV moved the royal court to his residence at Versailles, and in 1715 Louis XV began his reign in Versailles. While the King occasionally went hunting at Vincennes, the Court did not return.[7]

18th – early 19th century – Manufactory, prison, fortress

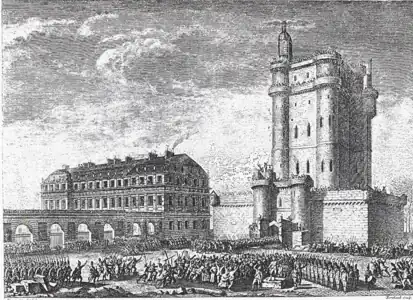

Storming of the keep by Revolutionaries (1791)

Storming of the keep by Revolutionaries (1791) The execution of the Duc d'Enghien in 1804 by William Miller after Turner

The execution of the Duc d'Enghien in 1804 by William Miller after Turner Anonymous watercolour of the moat. The weeping willow marks the spot where the Duc d’Enghien was executed

Anonymous watercolour of the moat. The weeping willow marks the spot where the Duc d’Enghien was executed.jpg.webp) General Daumesnil : "I shall surrender Vincennes when I get my leg back".

General Daumesnil : "I shall surrender Vincennes when I get my leg back".

Following the royal departure in the early 18th century, an effort was made to turn the Chateau into a sort of pre-industrial park; the royal porcelain manufactory was opened in the Devil's Tower in 1740, but moved to a larger space in Sèvres in 1756. It was home for a time of an armaments factory and a porcelain factory, then an industrial bakery. It was used occasionally for horse races from 1777 until 1784. In 1787 the King put most of the buildings up for sale, but the sale was interrupted by the French Revolution. The Chateau took on a new role as a military base and prison. [7]

Long before the French Revolution, notable prisoners had been held at the Chateau. Early prisoners included the future King Henry IV in 1574, Henri II de Condé (1652–1664); Nicolas Fouquet, the royal minister of finance of Louis XIV (September 1661); and the writer Denis Diderot. In 1680 Catherine Deshayes Monvoisin or La Voisin was one of more famous poisoners tortured and imprisoned at the chateau during the Affair of the Poisons.[8]

The Marquis de Sade was held there from 1777 to 1784, the writer Honoré Mirabeau from 1777 to 1784, and the famous swindler Jean Henri Latude, who escaped twice from the Vincennes and once from the Bastille. In 1784, after Mirabeau wrote a series of articles which exposed the abuses of the royal judicial system and the practice of keeping prisoners without trial, the use of the keep as prison was discontinued. [9]

At the end of February 1791, a mob of more than a thousand workers from the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, encouraged by members of the Cordeliers Club and led by Antoine Joseph Santerre, marched out to the château, which, rumour had it, was being readied on the part of the Crown for political prisoners, and with crowbars and pickaxes set about demolishing it, as the Bastille had recently been demolished. The work was interrupted by the Marquis de Lafayette who took several ringleaders prisoners, to the jeers of the Parisian workers.[10]

Following the French Revolution, the chateau was denounced as a symbol of oppression, but then was used again by Napoleon I to hold prisoners transferred from the Temple Prison in Paris, Napoleon demolished the Temple prison to prevent it from becoming a royalist shrine to Marie Antoinette, who had been held there. Two historical items from the Temple Prison are displayed at Vincennes; an armoured prison cell door, and a stove of ceramic tiles which had originally been in the cell of Marie Antoinette.[9]

During the reign of Napoleon, the chateau and its buildings underwent considerable reconstruction to serve as a military arsenal. A new wooden floor divided the Sainte-Chapelle into upper and lower levels, and it was turned into a storehouse for munitions. The Pavilion of the King and the Pavilion of the Queen became barracks for the garrison. Most of the towers of the surrounding wall, which were in a poor state of repair, were demolished, with the exception of the Tower of the Village, which still has its original height, and the Tower of the Woods, which had collapsed earlier.[9] The moat of the chateau was also the site of a famous execution, that of Duc d'Enghien, which took place on 21 March 1804. He was accused of trying the reinstate the royal government. A willow tree in the moat was planted to mark the place he was executed, and is still there today.[7]

In 1814, after Napoleon's defeat in Russia, as the allied armies of the Sixth Coalition approached Paris, the chateau was commanded by General Pierre Yrieix Daumesnil. Daumesnil had a wooden leg, replacing a limb he lost at the Battle of Wagram (5–6 July 1809). When the allies demanded his surrender, Daumenil responded, "I shall surrender Vincennes when I get my leg back". He finally agreed to give up the fortress only when ordered to do by the newly restored King, Louis XVIII.

Late 19th – military base and public park

During the Restoration and the July Monarchy, in the first half of the 19th century, the chateau and park were used by military, particularly the artillery; an artillery school was opened there in 1826. The surrounding park was used for military exercises and as a firing range. In the first part of the 19th century three separate forts were constructed within the park to serve as part of the defences of the city. In the mid-century, the separate forts were connected together into one very large military complex. The buildings of the chateau itself and its surroundings were the park as part of the new fortifications of the city. Some parts of the medieval complexes were modified to fit into the new defensive plan.[11]

Under Napoleon III, the Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes was declared an historical landmark, and in 1854 restoration of the chapel was begun by Eugene Viollet-le-Duc.The keep of the chateau was given landmark status in 1913, though restoration did not begin until after the First World War. [11]

Beginning just before 1860, the Emperor Louis Napoleon also began to develop an extensive new public park to the southeast of Paris, the Bois de Vincennes, modelled after the Bois de Boulogne he had begun on the other side of the city. The territory of the Bois de Vincennes, with the exception of the military bases, was ceded to the City of Paris on 24 July 1860, and became part of the XII arrondissement of Paris.[12]

On March 20, 1871, two days after the Paris Commune seized power in the city, Commune soldiers came to the Chateau and fraternised with the regular army soldiers. The Chateau surrendered to the Commune without a fight. A few weeks later, on 27 May, after the regular French army had recaptured Paris from the Commune, the Chateau was the last holdout where the red flag still flew. . A colonel of the regular army arrived and negotiated the surrender of the remaining Communards. The soldiers left peacefully, while some of the officers who had joined the Commune were arrested, tried and shot in the moat of the chateau. A plaque on the wall of the moat marks the place. [12]

20th century – Command post

During the First World War, the Dutch-born German spy Mata Hari was executed by a firing squad on October 15, 1917, in the moat of the Chateau.[13]

The restoration of the chateau was halted in 1936 by concerns about the rising threat from Nazi Germany. Beginning in that year, a large underground bunker was dug beneath the Pavilion of the Queen in the southeast corner, to serve as the headquarters of the chief of staff. The generals Maurice Gamelin and then Maxime Weygand directed the defense of France from there, until they were overwhelmed by the German Blitzkrieg. France surrendered on June 14, 1940. The Germans then used it as a base for their own soldiers, as well as a prison where French Resistance members were held. One of the first members of the French Resistance, Jacques Bonsergent, was tried and executed there on November 10, 1940.[14] On 20 August 1944, during the battle for the Liberation of Paris, 26 policemen and members of the Resistance arrested by soldiers of the Waffen-SS were executed in the eastern moat of the fortress, and their bodies thrown in a common grave.[15]

On the evening of August 24, 1944, the same day that the armoured division of General Leclerc reached the centre of Paris, the German forces occupying the Château set off explosives in the three storage areas of munitions, badly damaging the Pavilions of the King and Queen and opening a gap in the wall between the entry pavilion and tower of Paris, before they withdrew. The next day the 4th U.S. infantry division reached the Château and the eastern neighbourhoods of Paris.[16]

In 1948 the Chateau became the headquarters of France's Defence Historical Service, which maintains a museum in the keep. A major campaign began in 1986 to preserve and restore the architectural heritage of the Château.[17]

Plan and Description

Plan of the Château

Plan of the Château Wide angle view of the keep

Wide angle view of the keep The Sainte-Chapelle and the Queen's Pavilion

The Sainte-Chapelle and the Queen's Pavilion.jpg.webp) The keep and the King's Pavilion

The keep and the King's Pavilion

Only traces remain of the earlier castle and the substantial remains date from the 14th century. The castle forms a rectangle whose perimeter is more than a kilometer in length (330 m × 175 m, 1,085 ft × 575 ft). It has six towers and three gates, each originally 42 metres (138 ft) high, and is surrounded by a deep stone lined moat. The towers of the grande enceinte now stand only to the height of the walls, having been demolished in the 1800s, save the Tour du Village on the north side of the enclosure. The south end consists of two wings facing each other, the Pavillon du Roi and the Pavillon de la Reine, built by Louis Le Vau.

The Keep

The Donjon or Keep

The Donjon or Keep_-_2020-10-10_-_31.jpg.webp) Interior of the Keep

Interior of the Keep Sixth floor of the Keep

Sixth floor of the Keep

The Donjon or Keep of Vincennes was finished in 1369–70. It is fifty metres (160 ft) high, the highest of its kind in Europe. Its walls are 16.5 metres (54 ft) wide on each side, and at each corner is tower 6.6 metres (22 ft) in diameter, the same height as the building. An additional tower, the height of the rest, is attached to the north of the northwest tower, providing support the whole structure and also containing latrines for all five levels of the keep. The wall at the base of the keep are 3.26 meters, or ten feet, thick. It served as both a royal residence and a very visible symbol of royal power.[18]

The keep is one of the first known examples of rebar usage.[19] Each of the eight floors has a central room about ten meters on each side. with a height varying from seven to eight metres (23 to 26 ft). Each of the lower four floors have s central column which reinforces the vaulted ceiling. The columns were decorated with sculpture and painted in bright colors.[18]

One striking feature of the construction was the use of iron bars to strengthen the structure. More than two and half kilometres (1.6 mi) of iron bars, in various shapes, were built into the structure. Iron bars reinforced the doorways, windows and the ceilings of the corridors, and, unusually, belts of iron bars surrounded the entire tower at the ground level, fifth level and sixth level.[16]

In the Middle Ages the only access to the Keep was on the first floor, by a bridge from the terrace of the chatelet, where the King's offices were located. A narrow stairway, within the south wall. The two entrances on the ground floor were not added until the 18th century. When the keep was given an additional floor, and grand stairway was built connecting the two noble floors, the first and second.[16]

Keep interior

_Ch%C3%A2teau_Donjon_Chambre_du_Roi_01.JPG.webp) Bedchamber of the King

Bedchamber of the King%252C_ch%C3%A2teau%252C_donjon%252C_chambre_du_Roi%252C_chapiteau_central_2.jpg.webp) Central column in chamber of the King

Central column in chamber of the King%252C_ch%C3%A2teau%252C_donjon%252C_chambre_du_Roi%252C_chemin%C3%A9e_2.jpg.webp) Decoration of fireplace in the chamber of the King

Decoration of fireplace in the chamber of the King_Ch%C3%A2teau_Donjon_Chambre_du_Roi_14.JPG.webp) Sculpture at the base of a vault, chamber of the King

Sculpture at the base of a vault, chamber of the King

- The ground floor of the Keep has wells and the remains of a large fireplace. It was probably originally used by royal servants. It was largely rebuilt when the building was used as a prison.

- The first floor contained the meeting hall of the Council of the King, and was also used when needed for bedchambers of the Queen and others close to the King. The walls were originally covered with oak panels, some of which are still in place. Studies of the wood indicate that it was cut between 1367 and 1371 in the Baltic region or present-day Poland.[20]

- The second floor was occupied by the bedchamber of the King, and has vestiges of the decoration added by Charles V of France when he rebuilt it 1367–38. The walls were originally covered with oak panels, and the vaulted ceiling was decorated with sculpted keystones and consoles and painted fleurs-de-lys and the coat-of-arms of the King, against a blue background, still visible. A small oratory is set into the north wall, though its wood panelling has disappeared.[20]

- The third floor has the same plan as the second, but lacks the ornate decoration of the royal floor. It was probably used by important guests of the King.

- The fourth, fifth and sixth floors, which lack ornament, were probably used by domestic servants or soldiers. They were also used to store munitions for the weapons placed at the windows of the fourth floor and on the terraces of tower of latrines and the main body of the keep. The sixth floor has no windows and a ceiling only two meters high, and a single entrance. Beginning in 1752, the upper floors were used primarily as prison cells. The bars in the windows and doors date from that period. The extensive and elaborate graffiti still found on the walls on the upper floors also dates from the 17th and 18th century.[21]

Wall of the Keep and Entry Pavilion

The Keep is surrounded by a rectangular stone wall, or "enceinte" about 50 metres (160 ft) long one each side, 11.5 metres (38 ft) high, and 1.1 metres (3 ft 7 in) thick. It is crenelated at the top level with a walkway that was originally open but was given a tile roof in the 15th century and then the present slate roof. At each of the four corners is an Echauguette, a small watch tower that protrudes outward, to give better oversight of the walls. In the northeast corner of the walkway, next to the chatelet, is a group of rooms which originally were part of the working office of the King, on the second floor of the chatelet. They include a small chapel, a hall, and a chamber.[22]

The Sainte-Chapelle

_-_2020-10-10_-_17.jpg.webp) West front of Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes

West front of Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes Flamboyant west front of the Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes

Flamboyant west front of the Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes Interior of the Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes

Interior of the Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes

The Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes, the royal chapel of the residence, was built on the model of the Sainte Chapelle of the Palais de la Cité in Paris, though the plan was modified to have a single level, rather than two. Work began under Charles V of France in 1379, at the end of his reign. The exterior and interior sculpture was largely finished between 1390 and 1410. The west front was finished last; work was resumed in 1520, and it was inaugurated by Henry II of France in 1552. The west front is a good example of the late Gothic Flamboyant style, with three gabled arches one atop the other, framing and echoing the elaborate curling designs of the rose window. The stained glass windows of the interior reflected the changing style; the windows of the choir were Rayonnant Gothic, while those of the nave were Flamboyant.[23]

The Chapel suffered particularly from the vandalism of the French Revolution. Most all of the stained glass and the sculpture on tympanum and portals was smashed, but a few notable examples of 15th century sculpture survived, notably a sculpture of the Holy Trinity in the upper arches over the west portal.[23] The outside walls are supported by enormous buttresses between the windows, each crowned by an ornate spire, giving them additional weight.[24]

_-_2020-10-10_-_11.jpg.webp) Stained glass windows of the apse

Stained glass windows of the apse%252C_ch%C3%A2teau%252C_sainte-chapelle%252C_cl%C3%A9_de_vo%C3%BBte_de_la_3e_trav%C3%A9e.jpg.webp) Keystone of a vault with initials of Henry II and Catherine de Médicis

Keystone of a vault with initials of Henry II and Catherine de Médicis_Ch%C3%A2teau_Sainte-Chapelle_Culot_06.JPG.webp) Sculpted corbel in the chapel

Sculpted corbel in the chapel

The nave and choir of the interior form a single vessel with five traverses. The oratories of the King and Queen are placed just before the choir. The summit of the vaults, where the ribs meet, are decorated with ornamental keystones, some with the coats-of-arms of Isabeau of Bavaria and Charles V of France. The painted decoration on some of the later vaults displays the H of Henry II of France and a K for Catherine de Medici.[24]

The stained glass windows of the nave were installed between 1556 and 1559. Those in the nave were almost entirely destroyed in the French Revolution; only drawings remain. Some of the windows of the apse survived. They illustrate the Apocalypse as recounted in the Gospel of Saint John. They were substantially restored in the 19th century under Louis Napoleon and again the 20th century.[25]

The Pavilions of the King and Queen

Pavilion of the King

Pavilion of the King Pavilion of the Queen

Pavilion of the Queen

Louis XIII built the King's pavilion in the southwest corner between 1610 and 1617 near the beginning of his reign. Only the west facade of this building is still visible. In 1654–58, the royal architect Louis Le Vau enlarged the building surrounding the old structure with a new structure, in the French classical style. The new building has the same length as the old pavilion, but is twice as wide. The Pavilion of the Queen was built between 1658 and 1660, following the same basic design.

The Pavilion of the King, three stories high, was built at the edge of a garden. The apartment of the King had five rooms, located on the first floor, looking west over the garden. The Queen's apartment in her pavilion followed the same plan, overlooking the courtyard. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the interiors fell into disrepair, then were almost totally destroyed, with the exception of some portions of the painted ceilings; the Germans had stored explosives in the two pavilions, and these exploded in fires set by the departing occupiers in August 1944.[24]

The Louis XIV Reading Room in the Pavilion of the King

The Louis XIV Reading Room in the Pavilion of the King_plafond.jpg.webp) Ceiling from the Pavilion of the King, now in the Egyptian collection of the Louvre Museum, room 639

Ceiling from the Pavilion of the King, now in the Egyptian collection of the Louvre Museum, room 639_2.jpg.webp) Ceiling from Pavilion of the King, now in the Egyptian collection, Room 639 of the Louvre Museum

Ceiling from Pavilion of the King, now in the Egyptian collection, Room 639 of the Louvre Museum

Fortunately, some portions of the painted and sculpted ceilings of the royal pavilions were saved in the 19th century; King Louis Philippe had a ceiling dismantled and transported from Vincennes to the Louvre Museum, where it was installed in room 639, a display of Egyptian Antiquities, where it can be seen today.[26]

See also

- Fort Neuf de Vincennes, built to the east of the fortress beginning in 1840 to provide an up-to-date artillery platform as part of the Thiers Wall defences of Paris; now a military headquarters.

- List of tourist attractions in Paris

Sources

- ↑ It was used as the CnC Gamelin's HQ

- ↑ Chapelot 2003, p. 1,65–66.

- 1 2 Chapelot 2003, p. 4–5.

- 1 2 3 4 Chapelot 2003, p. 8.

- ↑ Chapelot 2003, p. 14-14.

- ↑ Chapelot 2003, p. 23.

- 1 2 3 Chapelot 2003, p. 24–27.

- ↑ Mossiker, Frances (1969). The Affair of the Poisons: Louis XIV, Madame de Montespan, and one of History's great Unsolved Mysteries. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 213–215. ISBN 0-7221-6245-6.

- 1 2 3 Chapelot 2003, p. 29.

- ↑ Christopher Hibbert, The Days of the French Revolution 1980:133f.

- 1 2 Chapelot 2003, p. 31–33.

- 1 2 Chapelot 2003, p. 33.

- ↑ "15 octobre 1917. Le jour où Mata Hari est fusillée au château de Vincennes." "Le Point", August 30, 2018

- ↑ Chapelot 2003, p. 35.

- ↑ "La vocation militaire du Château". Ville de Vincennes. Archived from the original on 2015-09-01. Retrieved 2015-07-06.

- 1 2 3 Chapelot 2003, p. 36-37.

- ↑ Chapelot 2003, p. 37.

- 1 2 Chapelot 2003, p. 42-43.

- ↑ "Le donjon de Vincennes livre son histoire".

- 1 2 Chapelot 2003, p. 44.

- ↑ Chapelot 2003, p. 48.

- ↑ Chapelot 2003, p. 43.

- 1 2 Chapelot 2003, p. 52.

- 1 2 3 Chapelot 2003, p. 56-57.

- ↑ Chapelot 2003, p. 58.

- ↑ Chapelot 2003, p. 60-61.

Bibliography

- Chapelot, Jean (2003). Le château de Vincennes (in French). Paris: Editions du Patrimoine- Centre des monuments nationaux. ISBN 978-2-85822-676-4.

- Frank McCormick, "John Vanbrugh's Architecture: Some Sources of His Style" The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 46.2 (June 1987) pp. 135–144.

- Jean Mesqui, Châteaux forts et fortifications en France (Paris: Flammarion, 1997)

Gallery

The chapel, one of Le Vau's isolated ranges, and the queen's pavilion at the right

The chapel, one of Le Vau's isolated ranges, and the queen's pavilion at the right.jpg.webp) Northern wall and main entrance to the castle.

Northern wall and main entrance to the castle. South entry to the Chateau

South entry to the Chateau Another view of the moat

Another view of the moat A view of the top of the keep

A view of the top of the keep Southwest view of the Sainte-Chapelle

Southwest view of the Sainte-Chapelle North entry to the Chateau

North entry to the Chateau

External links

- Website of the Château

- Château de Vincennes – The official website of France (in English)

- Information on structurae.de

- French web site about history of Castle of Vincennes, with many illustrations.

- Base Mérimée: Château de Vincennes et ses abords, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- Base Mérimée: Château fort, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)