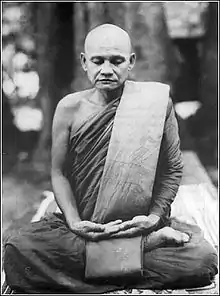

Ajahn Chah | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal | |

| Born | Chah Chuangchot ชา ช่วงโชติ 17 June 1918 Ubon Ratchathani, Thailand |

| Died | 16 January 1992 (aged 73) Ubon Ratchathani, Thailand |

| Religion | Buddhism |

| School | Theravāda |

| Lineage | Thai Forest Tradition |

| Dharma names | Subhaddo สุภทฺโท |

| Monastic name | Phra Bodhiñāṇathera พระโพธิญาณเถร |

| Order | Mahā Nikāya |

| Thai Forest Tradition | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bhikkhus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sīladharās | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related Articles | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ajahn Chah (17 June 1918 – 16 January 1992) was a Thai Buddhist monk. He was an influential teacher of the Buddhadhamma and a founder of two major monasteries in the Thai Forest Tradition.

Respected and loved in his own country as a man of great wisdom, he was also instrumental in establishing Theravada Buddhism in the West. Beginning in 1979 with the founding of Cittaviveka (commonly known as Chithurst Buddhist Monastery)[1] in the United Kingdom, the Forest Tradition of Ajahn Chah has spread throughout Europe, the United States and the British Commonwealth. The dhamma talks of Ajahn Chah have been recorded, transcribed and translated into several languages.

More than one million people, including the Thai royal family, attended Ajahn Chah's funeral in January 1993[2] held a year after his death due to the "hundreds of thousands of people expected to attend".[3] He left behind a legacy of dhamma talks, students, and monasteries.

Name

Ajahn Chah (Thai: อาจารย์ชา) was also commonly known as Luang Por Chah (Thai: หลวงพ่อชา). His birth name was Chah Chuangchot (Thai: ชา ช่วงโชติ),[4]: 21 his Dhamma name was Subhaddo (Thai: สุภทฺโท),[4]: 38 and his monastic title was Phra Bodhiñāṇathera (Thai: พระโพธิญาณเถร).[4]: 184 [5]

Early life

Ajahn Chah was born on 17 June 1918 near Ubon Ratchathani in the Isan region of northeast Thailand. His family were subsistence farmers. As is traditional, Ajahn Chah entered the monastery as a novice at the age of nine, where, during a three-year stay, he learned to read and write. The definitive 2017 biography of Ajahn Chah Stillness Flowing[4] states that Ajahn Chah took his novice vows in March 1931 and that his first teacher as a novice was Ajahn Lang. He left the monastery to help his family on the farm, but later returned to monastic life on 16 April 1939, seeking ordination as a Theravadan monk (or bhikkhu).[6] According to the book Food for the Heart: The Collected Writings of Ajahn Chah, he chose to leave the settled monastic life in 1946 and became a wandering ascetic after the death of his father.[6] He walked across Thailand, taking teachings at various monasteries. Among his teachers at this time was Ajahn Mun, a renowned meditation master in the Forest Tradition. Ajahn Chah lived in caves and forests while learning from the meditation monks of the Forest Tradition. A website devoted to Ajahn Chah describes this period of his life:

For the next seven years Ajahn Chah practiced in the style of an ascetic monk in the austere Forest Tradition, spending his time in forests, caves and cremation grounds. He wandered through the countryside in quest of quiet and secluded places for developing meditation. He lived in tiger and cobra infested jungles, using reflections on death to penetrate to the true meaning of life.[6]

Thai forest tradition

.jpg.webp)

During the early part of the twentieth century Theravada Buddhism underwent a revival in Thailand under the leadership of teachers whose intentions were to raise the standards of Buddhist practise throughout the country. One of these teachers was Ajahn Mun. Ajahn Chah continued Ajahn Mun's high standards of practice when he became a teacher.[7]

The monks of this tradition keep very strictly what they believe to be the original monastic rule laid down by the Buddha known as the vinaya. The early major schisms in the Buddhist sangha were largely due to disagreements over which set of training rules should be applied. Some adopted a more flexible set, whereas others adopted a more strict one, both sides believing to follow the rules as the Buddha had framed them. The Theravada tradition is the heir to the latter view. An example of the strictness of the discipline might be the rule regarding eating: they uphold the rule to only eat between dawn and noon. In the Thai Forest Tradition, monks and nuns go further and observe the 'one eaters practice', whereby they only eat one meal during the morning. This special practice is one of the thirteen dhutanga, optional ascetic practices permitted by the Buddha that are used on an occasional or regular basis to deepen meditation practice and promote contentment with subsistence. Other examples of these practices are sleeping outside under a tree, or dwelling in secluded forests or graveyards.

Monasteries founded

After years of wandering, Ajahn Chah decided to plant roots in an uninhabited grove near his birthplace. In 1954, Wat Nong Pah Pong monastery was established, where Ajahn Chah could teach his simple, practice-based form of meditation. He attracted a wide variety of disciples, which included, in 1966, the first Westerner, Venerable Ajahn Sumedho.[6] Wat Nong Pah Pong [8] includes over 250 branches throughout Thailand, as well as over 15 associated monasteries and ten lay practice centers around the world.[6]

In 1975, Wat Pah Nanachat (International Forest Monastery) was founded with Ajahn Sumedho as the abbot. Wat Pah Nanachat was the first monastery in Thailand specifically geared towards training English-speaking Westerners in the monastic Vinaya, as well as the first run by a Westerner.

In 1977, Ajahn Chah and Ajahn Sumedho were invited to visit the United Kingdom by the English Sangha Trust who wanted to form a residential sangha.[9] 1979 saw the founding of Cittaviveka (commonly known as Chithurst Buddhist Monastery due to its location in the small hamlet of Chithurst) with Ajahn Sumedho as its head. Several of Ajahn Chah's Western students have since established monasteries throughout the world.

Later life

By the early 1980s, Ajahn Chah's health was in decline due to diabetes. He was taken to Bangkok for surgery to relieve paralysis caused by the diabetes, but it was to little effect. Ajahn Chah used his ill health as a teaching point, emphasizing that it was "a living example of the impermanence of all things...(and) reminded people to endeavor to find a true refuge within themselves, since he would not be able to teach for very much longer".[6] Ajahn Chah would remain bedridden and ultimately unable to speak for ten years, until his death on 16 January 1992, at the age of 73.[10][3]

Notable Western students

- Ajahn Sumedho, founder and former abbot of Chithurst Buddhist Monastery and Amaravati Buddhist Monastery, Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire, England

- Ajahn Khemadhammo, abbot of The Forest Hermitage, Warwickshire, England

- Ajahn Viradhammo, abbot of Tisarana Buddhist Monastery in Perth, Ontario, Canada

- Ajahn Sucitto, retired abbot of Cittaviveka monastery. A Dhamma writer.

- Ajahn Pasanno, abbot of Abhayagiri Monastery, Redwood Valley, California, USA

- Ajahn Amaro, abbot of Amaravati Monastery, Amaravati Buddhist Monastery, Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire England

- Ajahn Brahmavamso, abbot of Bodhinyana Monastery, Perth, Western Australia

- Ajahn Jayasaro, author of Stillness Flowing, the biography of Ajahn Chah, and former abbot of Wat Pah Nanachat

- Jack Kornfield, co-founder of Insight Meditation Society, Barre, Massachusetts, USA and Spirit Rock Meditation Center in Woodacre, California, USA

Bibliography

- Still Flowing Water: Eight Dhamma Talks (Thanissaro Bhikkhu, ed.). Metta Forest Monastery (2007).

- The Path to Peace. The Sangha, Wat Pah Nanachat (1996).

- Clarity of Insight. The Sangha, Wat Pah Nanachat (2000).

- A Still Forest Pool: The Insight Meditation of Achaan Chah (Jack Kornfield ed.). Theosophical Publishing House (1985). ISBN 0-8356-0597-3.

- Being Dharma: The Essence of the Buddha's Teachings. Shambahla Press, 2001. ISBN 1-57062-808-4.

- Food for the Heart (Ajahn Amaro, ed.). Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2002. ISBN 0-86171-323-0.

- Everything Is Teaching Us. Amaravati Publications, 2018. ISBN 978-1-78432-106-2.

- Living Dhamma. Amaravati Publications, 2018. ISBN 978-1-78432-099-7.

- A Taste of Freedom. Amaravati Publications, 2018. ISBN 978-1-78432-098-0.

- On Meditation. Amaravati Publications, 2018. ISBN 978-1-78432-101-7

- Bodhinyana. Amaravati Publications, 2018.ISBN 978-1-78432-097-3

Published by Buddhist Publication Society

References

- ↑ Website of Chithurst Buddhist Monastery

- ↑ "The State Funeral of Luang Por Chah". Ajahn Sucitto. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- 1 2 "Ajahn Chah Passes Away". Forest Sangha Newsletter. April 1992. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Ajahn Jayasāro (2017). Stillness Flowing: The Life and Teachings of Ajahn Chah (PDF). Bangkok: Panyaprateep Foundation. ISBN 978-616-7930-09-1.

- ↑ "แจ้งความสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี เรื่อง พระราชทานสัญญาบัตรตั้งสมณศักดิ์" (PDF). Royal Gazette. Vol. 90, no. 177. 28 December 1973. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Biography of Ajahn Chah". Wat Nong Pah Pong. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ↑ Wat Nong Pah Pong. "A Collection of Dhammatalks by Ajahn Chah". Everything Is Teaching Us. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ↑ "Website of Wat Nong Pah Pong". Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ↑ "Ajahn Sumedho (1934-)". BuddhaNet. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ↑ "Ajahn Chah: biography". Forest Sangha. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

External links

- Short biography and picture

- Video: detailed biography of Ajahn Chah

- Website of Wat Nong Pah Pong

- International branch monasteries of Wat Nong Pah Pong

- Ajahn Chah website – in English and other languages, with useful links and info

- PDF ebook: Recollections of Ajahn Chah, by various authors

- Ajahn Pasanno. Recollections of Ajahn Chah, Part 1 First of a series of 3 talks about Ajahn Chah, mp3 format

- Website of the Memorial to Ajahn Chah in Thai

Teachings

- PDF ebook: The Teachings of Ajahn Chah – main collection of Dhamma talks

- Dhamma talks by Ajahn Chah

- MP3 Dhamma talks by Ajahn Chah

- Ajahn Chah's talks in English and other languages

- Dhamma talks in MP3 audio format, with English translation

- Portal of the Ajahn Chah Sangha, including MP3s

- The Memorial to Ajahn Chah: Teachings in English and other languages