.JPG.webp)

A chaitya, chaitya hall, chaitya-griha, (Sanskrit:Caitya; Pāli: Cetiya) refers to a shrine, sanctuary, temple or prayer hall in Indian religions.[1][2] The term is most common in Buddhism, where it refers to a space with a stupa and a rounded apse at the end opposite the entrance, and a high roof with a rounded profile.[3] Strictly speaking, the chaitya is the stupa itself,[4] and the Indian buildings are chaitya halls, but this distinction is often not observed. Outside India, the term is used by Buddhists for local styles of small stupa-like monuments in Nepal, Cambodia, Indonesia and elsewhere. In Thailand a stupa, not a stupa hall, is called a chedi.[5] In the historical texts of Jainism and Hinduism, including those relating to architecture, chaitya refers to a temple, sanctuary or any sacred monument.[6][7][8]

Most early examples of chaitya that survive are Indian rock-cut architecture. Scholars agree that the standard form follows a tradition of free-standing halls made of wood and other plant materials, none of which has survived. The curving ribbed ceilings imitate timber construction. In the earlier examples, timber was used decoratively, with wooden ribs added to stone roofs. At the Bhaja Caves and the "Great Chaitya" of the Karla Caves, the original timber ribs survive; elsewhere marks on the ceiling show where they once were. Later, these ribs were rock-cut. Often, elements in wood, such as screens, porches, and balconies, were added to stone structures. The surviving examples are similar in their broad layout, though the design evolved over the centuries.[9]

The halls are high and long, but rather narrow. At the far end stands the stupa, which is the focus of devotion. Parikrama, the act of circumambulating or walking around the stupa, was an important ritual and devotional practice, and there is always clear space to allow this. The end of the hall is thus rounded, like the apse in Western architecture.[10] There are always columns along the side walls, going up to the start of the curved roof, and a passage behind the columns, creating aisles and a central nave, and allowing ritual circumambulation or pradakhshina, either immediately around the stupa, or around the passage behind the columns. On the outside, there is a porch, often very elaborately decorated, a relatively low entranceway, and above this often a gallery. The only natural light, apart from a little from the entrance way, comes from a large horseshoe-shaped window above the porch, echoing the curve of the roof inside. The overall effect is surprisingly similar to smaller Christian churches from the Early Medieval period, though early chaityas are many centuries earlier.[11]

Chaityas appear at the same sites like the vihara, a strongly contrasting type of building with a low-ceilinged rectangular central hall, with small cells opening, off it, often on all sides. These often have a shrine set back at the centre of the back wall, containing a stupa in early examples, or a Buddha statue later. The vihara was the key building in Buddhist monastic complexes, used to live, study and pray in. Typical large sites contain several viharas for every chaitya.[12]

Etymology

"Caitya", from a root cita or ci meaning "heaped-up", is a Sanskrit term for a mound or pedestal or "funeral pile".[1][13] It is a sacred construction of some sort, and has acquired different more specific meanings in different regions, including "caityavṛkṣa" for a sacred tree.[14]

According to K.L. Chanchreek, in early Jain literature, caitya mean ayatanas or temples where monks stayed. It also meant where the Jain idol was placed in a temple, but broadly it was a symbolism for any temple.[6][15] In some texts, these are referred to as arhat-caitya or jina-caitya, meaning shrines for an Arhat or Jina.[16] Major ancient Jaina archaeological sites such as the Kankali Tila near Mathura show Caitya-tree, Caitya-stupa, Caitya arches with Mahendra-dvajas and meditating Tirthankaras.[15]

The word caitya appears in the Vedic literature of Hinduism. In early Buddhist and Hindu literature, a caitya is any 'piled up monument' or 'sacred tree' under which to meet or meditate.[17][18][8] Jan Gonda and other scholars state the meaning of caitya in Hindu texts varies with context and has the general meaning of any "holy place, place of worship", a "memorial", or as signifying any "sanctuary" for human beings, particularly in the Grhya sutras.[1][17][7] According to Robert E. Buswell and Donald S. Lopez, both professors of Buddhist Studies, the term caitya in Sanskrit connotes a "tumulus, sanctuary or shrine", both in Buddhist and non-Buddhist contexts.[2]

The "chaitya arch" as a decorative motif

The "chaitya arch", gavaksha (Sanscrit gavākṣa), or chandrashala around the large window above the entrance frequently appears repeated as a small motif in decoration, and evolved versions continue into Hindu and Jain decoration, long after actual chaitya halls had ceased to be built by Buddhists. In these cases it can become an elaborate frame, spreading rather wide, around a circular or semi-circular medallion, which may contain a sculpture of a figure or head. An earlier stage is shown here in the entrance to Cave 19 at the Ajanta Caves (c. 475–500), where four horizontal zones of the decoration use repeated "chaitya arch" motifs on an otherwise plain band (two on the projecting porch, and two above). There is a head inside each arch.[19]

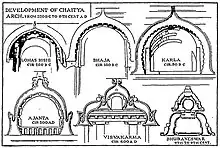

Development of the chaitya

Early Chaitya halls are known from the 3rd century BCE. They generally followed an apsidal plan, and were either rock-cut or freestanding.[20]

Rock-cut chaitya halls

The earliest surviving spaces comparable to the chaitya hall date to the 3rd century BCE. These are the rock-cut Barabar Caves (Lomas Rishi Cave and Sudama Cave), excavated during the reign of Ashoka by or for the Ajivikas, a non-Buddhist religious and philosophical group of the period. According to many scholars, these became "the prototype for the Buddhist caves of the western Deccan", particularly the chaitya halls excavated between the 2nd century BCE and 2nd century CE.[21]

Early chaityas enshrined a stupa with space for congregational worship by the monks. This reflected one of the early differences between early Buddhism and Hinduism, with Buddhism favoring congregational worship in contrast to Hinduism's individual approach. Early chaitya grhas were cut into living rock as caves. These served as a symbol and sites of a sangha congregational life (uposatha).[22][23]

The earliest rock-cut chaityas, similar to free-standing ones, consisted of an inner circular chamber with pillars to create a circular path around the stupa and an outer rectangular hall for the congregation of the devotees. Over the course of time, the wall separating the stupa from the hall was removed to create an apsidal hall with a colonnade around the nave and the stupa.[24]

The chaitya at Bhaja Caves is perhaps the earliest surviving chaitya hall, constructed in the second century BCE. It consists of an apsidal hall with a stupa. The columns slope inwards in the imitation of wooden columns that would have been structurally necessary to keep a roof up. The ceiling is barrel vaulted with ancient wooden ribs set into them. The walls are polished in the Mauryan style. It was faced by a substantial wooden facade, now entirely lost. A large horseshoe-shaped window, the chaitya-window, was set above the arched doorway and the whole portico-area was carved to imitate a multi-storeyed building with balconies and windows and sculptured men and women who observed the scene below. This created the appearance of an ancient Indian mansion.[25][24] This, like a similar facade at the Bedse Caves is an early example of what James Fergusson noted in the nineteenth century: "Everywhere ... in India architectural decoration is made up of small models of large buildings".[26]

In Bhaja, as in other chaityas, the entrance acted as the demarcation between the sacred and the profane. The stupa inside the hall was now completely removed from the sight of anyone outside. In this context, in the first century CE, the earlier veneration of the stupa changed to the veneration of an image of Gautama Buddha. Chaityas were commonly part of a monastic complex, the vihara.

The most important of rock-cut complexes are the Karla Caves, Ajanta Caves, Ellora Caves, Udayagiri and Khandagiri Caves, Aurangabad Caves and the Pandavleni Caves. Many pillars have capitals on them, often with carvings of a kneeling elephant mounted on bell-shaped bases.

Rock-cut hall, Sudama, Barabar Caves, dedicated in 257 BCE by Ashoka.

Rock-cut hall, Sudama, Barabar Caves, dedicated in 257 BCE by Ashoka. Rock-cut circular Chaitya hall with pillars, Tulja Caves, 1st century BCE

Rock-cut circular Chaitya hall with pillars, Tulja Caves, 1st century BCE Chaitya arch around the window, and repeated as a gavaksha motif with railings, Cave 9, Ajanta.

Chaitya arch around the window, and repeated as a gavaksha motif with railings, Cave 9, Ajanta. The window at the chaitya Cave 10, Ellora, c. 650

The window at the chaitya Cave 10, Ellora, c. 650 Timber ribs on the roof at the Karla Caves; the umbrella over the stupa is also wood

Timber ribs on the roof at the Karla Caves; the umbrella over the stupa is also wood.jpg.webp) Decorative chaitya arches and lattice railings, Bedse Caves, 1st century BCE

Decorative chaitya arches and lattice railings, Bedse Caves, 1st century BCE Stupa inside Cave 10, Ellora, the last chaitya hall built, the Buddha image now dominating the stupa.

Stupa inside Cave 10, Ellora, the last chaitya hall built, the Buddha image now dominating the stupa.

Freestanding chaitya halls

A number of freestanding constructed chaitya halls built in durable materials (stone or brick) have survived, the earliest from around the same time as the earliest rock-cut caves. There are also some ruins and groundworks, such as a circular type from the 3rd century BCE, the Bairat Temple, in which a central stupa was surrounded by 27 octagonal wooden pillars, and then enclosed in a circular brick wall, forming a circular procession path around the stupa.[20] Other significant remains of the bases of structural chaityas including those at Guntupalle, with many small round bases, and Lalitgiri.[27]

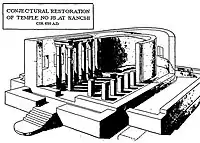

An apsidal structure in Sanchi has also been dated, at least partially, to the 3rd century BCE: the so-called Temple 40, one of the first instances of a free-standing temple in India.[28] Temple 40 has remains of three different periods, the earliest period dating to the Maurya age, which probably makes it contemporary to the creation of the Great Stupa. An inscription even suggests it might have been established by Bindusara, the father of Ashoka.[29] The original 3rd century BCE temple was built on a high rectangular stone platform, 26.52x14x3.35 metres, with two flights of stairs to the east and the west. It was an apsidal hall, probably made of timber. It was burnt down sometime in the 2nd century BCE.[30][31] Later, the platform was enlarged to 41.76x27.74 metres and re-used to erect a pillared hall with fifty columns (5x10) of which stumps remain. Some of these pillars have inscriptions of the 2nd century BCE.

The base and reconstructed columns on three sides of Temple 18 at Sanchi were presumably completed by wood and thatch; this dates from the 5th century CE, perhaps rebuilt on earlier foundations. This stands next to Temple 17, a small flat-roofed temple with a lower mandapa at the front, of the basic type that came to dominate both Buddhist and Hindu temples in the future. The two types were used in the Gupta Empire by both religions.[32]

The Trivikrama Temple, also named "Ter Temple", is a now a Hindu temple in the city of Ter, Maharashtra. It was initially a free-standing apsidal structure, which is characteristic of early Buddhist apsidal caityagriha design. This structure is still standing, but is now located at the back of the building, since a flat-roofed mandapa structure was probably added from the 6th century CE, when the temple was converted into a Hindu temple.[33] The apsidal structure seems to be contemporary to the great apsidal temple found in Sirkap, Taxila, which is dated to 30 BCE-50 CE.[33] It would have been built under the Satavahanas.[34] The front of the apsidal temple is decorated with a chaitya-arch, similar to those found in Buddhist rock-cut architecture.[33] The Trivikrama Temple is considered as the oldest standing structure in Maharashtra.[34]

Another Hindu temple which was converted from a Buddhist chaityagriha structure is the very small Kapoteswara temple at Chezarla in Guntur district; here the chamber is straight at both ends, but with a rounded brick vault for its roof, using corbelling.[35]

Remains of the circular Chaitya hall in Bairat Temple, 3rd century BCE.

Remains of the circular Chaitya hall in Bairat Temple, 3rd century BCE. Relief of a circular chaitya hall, Bharhut, circa 100 BCE.

Relief of a circular chaitya hall, Bharhut, circa 100 BCE.

Reconstruction of Sanchi Temple 40 (3rd century BCE).

Reconstruction of Sanchi Temple 40 (3rd century BCE). Trivikrama Temple with its chaitya arch.

Trivikrama Temple with its chaitya arch. The ancient Buddhist chaitya house at Ter.

The ancient Buddhist chaitya house at Ter. Remains of the chaitya hall in Chejarla Kapoteswara temple.

Remains of the chaitya hall in Chejarla Kapoteswara temple. Sanchi, Temple 18, from the apse end. Partly reconstructed.

Sanchi, Temple 18, from the apse end. Partly reconstructed. Conjectural reconstruction of Temple 18 by Percy Brown (now dated earlier)

Conjectural reconstruction of Temple 18 by Percy Brown (now dated earlier)

End of the chaitya hall

.jpg.webp)

Apparently the last rock-cut chaitya hall to be constructed was Cave 10 at Ellora, in the first half of the 7th century. By this time the role of the chaitya hall was being replaced by the vihara, which had now developed shrine rooms with Buddha images (easily added to older examples), and largely taken over their function for assemblies. The stupa itself had been replaced as a focus for devotion and meditation by the Buddha image, and in Cave 10, as in other late chaityas (for example Cave 26 at Ajanta, illustrated here), there is a large seated Buddha taking up the front of the stupa. Apart from this, the form of the interior is not much different from the earlier examples from several centuries before. But the form of the windows on the exterior has changed greatly, almost entirely dropping the imitation of wooden architecture, and showing a decorative treatment of the wide surround to the chaitya arch that was to be a major style in later temple decoration.[36]

The last stage of the freestanding chaitya hall temple may be exemplified by the Durga temple, Aihole, of the 7th or 8th century. This is apsidal, with rounded ends at the sanctuary end to a total of three layers: the enclosure to the sanctuary, a wall beyond this, and a pteroma or ambulatory as an open loggia with pillars running all round the building. This was the main space for parikrama or circumambulation. Above the round-ended sanctuary, now a room with a doorway, rises a shikara tower, relatively small by later standards, and the mandapa has a flat roof.[37] How long construction of chaitya halls in plant materials continued in villages is not known.

Parallels

- Toda huts

The broad resemblance between chaityas and the traditional huts still made by the Toda people of the Nilgiri Hills has often been remarked on.[39] These are crude huts built with wicker bent to produce arch-shaped roofs, but the models for the chaitya were presumably larger and much more sophisticated structures.[38]

- Lycian tombs

The similarity of the 4th century BCE Lycian barrel-vaulted tombs of Asia Minor, such as the tomb of Payava, with the Indian architectural design of the Chaitya (starting at least a century later from circa 250 BCE, with the Lomas Rishi caves in the Barabar caves group), suggests that the designs of the Lycian rock-cut tombs traveled to India,[40] or that both traditions derived from a common ancestral source.[41]

.jpg.webp)

Early on, James Fergusson, in his " Illustrated Handbook of Architecture", while describing the very progressive evolution from wooden architecture to stone architecture in various ancient civilizations, has commented that "In India, the form and construction of the older Buddhist temples resemble so singularly these examples in Lycia".[41] Ananda Coomaraswamy and others also noted that "Lycian excavated and monolithic tombs at Pinara and Xanthos on the south coast of Asia Minor present some analogy with the early Indian rock-cut caitya-halls", one of many common elements between Early Indian and Western Asiatic art.[42][43][44]

The Lycian tombs, dated to the 4th century BCE, are either free-standing or rock-cut barrel-vaulted sarcophagi, placed on a high base, with architectural features carved in stone to imitate wooden structures. There are numerous rock-cut equivalents to the free-standing structures. One of the free-standing tombs, the tomb of Payava, a Lykian aristocrat from Xanthos, and dated to 375-360 BCE, is visible at the British Museum. Both Greek and Persian influences can be seen in the reliefs sculpted on the sarcophagus.[45] The structural similarities with Indian Chaityas, down to many architectural details such as the "same pointed form of roof, with a ridge", are further developed in The cave temples of India.[46] Fergusson went on to suggest an "Indian connection", and some form of cultural transfer across the Achaemenid Empire.[47] Overall, the ancient transfer of Lycian designs for rock-cut monuments to India is considered as "quite probable".[40]

Anthropologist David Napier has also proposed a reverse relationship, claiming that the Payava tomb was a descendant of an ancient South Asian style, and that the man named "Payava" may actually have been a Graeco-Indian named "Pallava".[48]

Nepal

In Nepal, the meaning of the word "chaitya" is different. A Nepalese chaitya is not a building, but a shrine monument that consists of a stupa-like shape on top of a plinth, often very elaborately ornamented. They are typically placed in the open air, often in religious compounds, averaging around four to eight feet in height. They are constructed in the memory of a dead person by his or her family by the Sherpas, Magars, Gurungs, Tamangs, and Newars, among other people of Nepal. The Newar people of the Kathmandu Valley started adding images of the four Tathagatas on the chaitya's four directions, mainly after the twelfth century. They are constructed with beautifully carved stone and mud mortar. They are said to consist of the Mahābhūta— earth, air, fire, water, and space.[49]

Cambodia

In classical Cambodian art chaityas are boundary markers for sacred sites, generally made in sets of four, placed on the site boundary at the four cardinal directions. They generally take a pillar-like form, often topped with a stupa, and are carved on the body.[50]

Gallery

Cambodian sanctuary marker chaitya, Khleang style, c. 975–1010

Cambodian sanctuary marker chaitya, Khleang style, c. 975–1010

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 Kevin Trainor (1997). Relics, Ritual, and Representation in Buddhism: Rematerializing the Sri Lankan Theravada Tradition. Cambridge University Press. pp. 33–38, 89–90 with footnotes. ISBN 978-0-521-58280-3.

- 1 2 Robert E. Buswell Jr.; Donald S. Lopez Jr. (2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-1-4008-4805-8.

- ↑ Michell, 66–67; Harle, 48

- ↑ Harle (1994), 48

- ↑ "Chedi". 17 January 2023.

- 1 2 K.L. Chanchreek (2004). Jaina Art and Architecture: Northern and Eastern India. Shree. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-81-88658-51-0.

- 1 2 Jan Gonda (1980). Vedic Ritual. BRILL Academic. pp. 418–419. ISBN 90-04-06210-6.

- 1 2 Stella Kramrisch (1946). The Hindu Temple, Volume 1. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 147–149 with footnote 150. ISBN 978-81-208-0223-0.

- ↑ Michell, 66, 374; Harle, 48, 493; Hardy, 39

- ↑ Michell, 65–66

- ↑ Michell, 66–67; Harle, 48; R. C. Majumdar quoting James Fergusson on the Great Chaitya at Karla Caves:

"It resembles an early Christian church in its arrangement; consisting of a nave and side-aisles terminating in an apse or semi-dome, around which the aisle is carried... Fifteen pillars on each side separate the nave from the aisle..."

— Ancient India, Ramesh Chandra Majumdar, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1977, p.225 - ↑ Michell, 67

- ↑ Harle (1994), 26, 48

- ↑ Harle, 26, 48

- 1 2 Umakant Premanand Shah (1987). Jaina Iconography. Abhinav Publications. pp. 9–14. ISBN 978-81-7017-208-6.

- ↑ Mohan Lal Mehta (1969). Jaina Culture. P.V. Research Institute. p. 125.

- 1 2 M. Sparreboom (1985). Chariots in the Veda. BRILL Academic. pp. 63–72 with footnotes. ISBN 90-04-07590-9.

- ↑ Caitya, Encyclopaedia Britannica

- ↑ Michell, 69, 342; Harle, 48, 119

- 1 2 Chakrabarty, Dilip K. (2009). India: An Archaeological History: Palaeolithic Beginnings to Early Historic Foundations. Oxford University Press. p. 421. ISBN 9780199088140.

- ↑ Pia Brancaccio (2010). The Buddhist Caves at Aurangabad: Transformations in Art and Religion. BRILL Academic. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-90-04-18525-8.

- ↑ James C. Harle (1994). The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent. Yale University Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-300-06217-5.

- ↑ Michael K. Jerryson (2017). The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Buddhism. Oxford University Press. pp. 445–446. ISBN 978-0-19-936238-7.

- 1 2 Dehejia, V. (1972). Early Buddhist Rock Temples. Thames and Hudson: London. ISBN 0-500-69001-4.

- ↑ ASI, "Bhaja Caves" Archived 2013-08-10 at the Wayback Machine; Michell, 352

- ↑ Quoted in Hardy, 18

- ↑ Group of Buddhist Monuments, Guntupalli. ASI Archived 2013-12-30 at the Wayback Machine; ASI, Lalitgiri Archived 2014-09-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Buddhist Architecture, Lee Huu Phuoc, Grafikol 2009, p.147

- ↑ Singh, Upinder (2016). The Idea of Ancient India: Essays on Religion, Politics, and Archaeology (in Arabic). SAGE Publications India. ISBN 9789351506454.

- ↑ Abram, David; (Firm), Rough Guides (2003). The Rough Guide to India. Rough Guides. ISBN 9781843530893.

- ↑ Marshall, John (1955). Guide to Sanchi.

- ↑ Harle, 219-220

- 1 2 3 Le, Huu Phuoc (2010). Buddhist Architecture. Grafikol. p. 237. ISBN 9780984404308.

- 1 2 Michell, George (2013). Southern India: A Guide to Monuments Sites & Museums. Roli Books Private Limited. p. 142. ISBN 9788174369031.

- ↑ Ahir, D. C. (1992). Buddhism in South India. South Asia Books. p. 72. ISBN 9788170303329.; Harle, 218

- ↑ Harle, 132

- ↑ Harle, 220-221

- 1 2 J. Leroy Davidson (1956), Review: The Art of Indian Asia: Its Mythology and Transformations, The Art Bulletin, vol. 38, no. 2, 1956, pp. 126–127

- ↑ Narayan Sanyal, Immortal Ajanta, p. 134, Bharati Book Stall, 1984

- 1 2 Ching, Francis D.K; Jarzombek, Mark M.; Prakash, Vikramaditya (2017). A Global History of Architecture. John Wiley & Sons. p. 707. ISBN 9781118981603.

- 1 2 The Illustrated Handbook of Architecture Being a Concise and Popular Account of the Different Styles of Architecture Prevailing in All Ages and All Countries by James Fergusson. J. Murray. 1859. p. 212.

- ↑ Coomaraswamy, Ananda K. (1972). History of Indian and Indonesian art. p. 12.

- ↑ Bombay, Asiatic Society of (1974). Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bombay. Asiatic Society of Bombay. p. 61.

- ↑ "The Lycian tombs at Pinara and Xanthos, on the south-coast of Asia Minor, were excavated like the early Indian rock-hewn chaitya-hall" in Joveau-Dubreuil, Gabriel (1976). Vedic antiquites. Akshara. p. 4.

- ↑ M. Caygill, The British Museum A-Z compani (London, The British Museum Press, 1999) E. Slatter, Xanthus: travels and discovery (London, Rubicon Press, 1994) A.H. Smith, A catalogue of sculpture in -1, vol. 2 (London, British Museum, 1900)

- ↑ Fergusson, James; Burgess, James (1880). The cave temples of India. London : Allen. p. 120.

- ↑ Fergusson, James (1849). An historical inquiry into the true principles of beauty in art, more especially with reference to architecture. London, Longmans, Brown, Green, and Longmans. pp. 316–320.

- ↑ According to David Napier, author of Masks, Transformation, and Paradox, "In the British Museum we find a Lycian building, the roof of which is clearly the descendant of an ancient South Asian style.", "For this is the so-called "Tomb of Payava" a Graeco-Indian Pallava if ever there was one." in "Masks and metaphysics in the ancient world: an anthropological view" in Malik, Subhash Chandra; Arts, Indira Gandhi National Centre for the (2001). Mind, Man, and Mask. Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. p. 10. ISBN 9788173051920.. David Napier biography here and here

- ↑ "Shikarakuta (small temple) Chaitya". Asianart.com. Retrieved 2012-04-24.

- ↑ Jessup, 109–110, 209

References

- Dehejia, V. (1997). Indian Art. Phaidon: London. ISBN 0-7148-3496-3

- Hardy, Adam, Indian Temple Architecture: Form and Transformation : the Karṇāṭa Drāviḍa Tradition, 7th to 13th Centuries, 1995, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 8170173124, 9788170173120, google books

- Harle, J.C., The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, 2nd edn. 1994, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, ISBN 0300062176

- Jessup, Helen Ibbetson, Art and Architecture of Cambodia, 2004, Thames & Hudson (World of Art), ISBN 050020375X

- Michell, George, The Penguin Guide to the Monuments of India, Volume 1: Buddhist, Jain, Hindu, 1989, Penguin Books, ISBN 0140081445

External links

- Evolution of Chaitya Halls compiled by students of School of Planning & Architecture, New Delhi