| Ruthenian | |

|---|---|

| рускїй ѧзыкъ[1][2] | |

| Native to | East Slavic regions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth |

| Extinct | Developed into Belarusian, Ukrainian and Rusyn |

Early forms | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Grand Duchy of Lithuania[3][4] (later replaced by Polish[4]) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

orv-olr | |

| Glottolog | None |

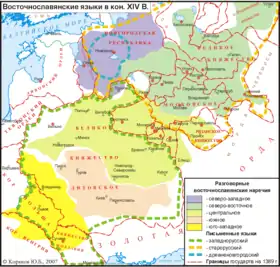

Ruthenian (рускаꙗ мова, рускїй ѧзыкъ;[1][2] see also other names) is an exonymic linguonym for a closely related group of East Slavic linguistic varieties, particularly those spoken from the 15th to 18th centuries in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and in East Slavic regions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Regional distribution of those varieties, both in their literary and vernacular forms, corresponded approximately to the territories of the modern states of Belarus and Ukraine. By the end of the 18th century, they gradually diverged into regional variants, which subsequently developed into the modern Belarusian, Ukrainian, and Rusyn languages.[5][6][7][8]

In the Austrian and Austro-Hungarian empires, the same term (German: ruthenische Sprache; Hungarian: Rutén nyelv) was employed continuously (up to 1918) as an official exonym for the entire East Slavic linguistic body within its borders.[9]

Several linguistic issues are debated among linguists: various questions related to classification of literary and vernacular varieties of this language; issues related to meanings and proper uses of various endonymic (native) and exonymic (foreign) glottonyms (names of languages and linguistic varieties); questions on its relation to modern East Slavic languages, and its relation to Old East Slavic (the colloquial language used in Kievan Rus' in the 10th through 13th centuries).[10]

Nomenclature

Since the term Ruthenian language was exonymic (foreign, both in origin and nature), its use was very complex, both in historical and modern scholarly terminology.[12]

Names in contemporary use

Contemporary names, that were used for this language from the 15th to 18th centuries, can be divided into two basic linguistic categories, the first being endonyms (native names, used by native speakers as self-designations for their language), and the second exonyms (names in foreign languages).

Common endonyms:

- Ruska(ja) mova, written in various ways, as: руска(ꙗ) мова, and also as: рускїй ѧзыкъ.

- Prosta(ja) mova (meaning: the simple speech, or the simple talk), also written in various ways, as: прост(ѧ) мова or простй ѧзыкъ (Old Belarusian / Old Ukrainian: простый руский (язык) or простая молва, проста мова) – publisher Hryhorii Khodkevych (16th century). Those terms for simple vernacular speech were designating its diglossic opposition to literary Church Slavonic.[13][14][15]

- In contemporary Russia, it was sometimes also referred to (in territorial terms) as Litovsky (Russian: Литовский язык / Lithuanian). Also by Zizaniy (end of the 16th century), Pamva Berynda (1653).

Common exonyms:

Names in modern use

Modern names of this language and its varieties, that are used by scholars (mainly linguists), can also be divided in two basic categories, the first including those that are derived from endonymic (native) names, and the second encompassing those that are derived from exonymic (foreign) names.

Names derived from endonymic terms:

- One "s" terms: Rus’ian, Rusian, Rusky or Ruski, employed explicitly with only one letter "s" in order to distinguish this name from terms that are designating modern Russian.[17]

- West Russian language or dialect (Russian: западнорусский язык, западнорусское наречие) – terms used mainly by supporters of the concept of the Proto-Russian phase, especially since the end of the 19th century. Employed by authors such as Karskiy and Shakhmatov.[18]

- Old Belarusian language (Belarusian: Старабеларуская мова) – term used by various Belarusian and some Russian scholars, and also by Kryzhanich. The denotation Belarusian (language) (Russian: белорусский (язык)) when referring both to the post-19th-century language and to the older language had been used in works of the 19th-century Russian researchers Fyodor Buslayev, Ogonovskiy, Zhitetskiy, Sobolevskiy, Nedeshev, Vladimirov and Belarusian researchers, such as Karskiy.[19]

- Old Ukrainian language (Ukrainian: Староукраїнська мова) – term used by various Ukrainian and some other scholars.

- Lithuanian-Russian language (Russian: литовско-русский язык) – regionally oriented designation, used by some 19th-century Russian researchers such as: Keppen, archbishop Filaret, Sakharov, Karatayev.

- Lithuanian-Slavic language (Russian: литово-славянский язык) – another regionally oriented designation, used by 19th-century Russian researcher Baranovskiy.[20]

- Chancery Slavonic, or Chancery Slavic – a term used for the written form, based on Old Church Slavonic, but influenced by various local dialects and used in the chancery of Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[14][21]

Names derived from exonymic terms:

- Ruthenian or Ruthene language – modern scholarly terms, derived from older Latin exonyms (Latin: lingua ruthenica, lingua ruthena), commonly used by scholars who are writing in English and other western languages, and also by various Lithuanian and Polish scholars.[22][23]

- Ruthenian literary language, or Literary Ruthenian language – terms used by the same groups of scholars in order to designate more precisely the literary variety of this language.[7]

- Ruthenian chancery language, or Chancery Ruthenian language – terms used by the same groups of scholars in order to designate more precisely the chancery variety of this language, used in official and legal documents of the Grand Dutchy of Lithuania.[24]

- Ruthenian common language, or Common Ruthenian language – terms used by the same groups of scholars in order to designate more precisely the vernacular variety of this language.[25]

- North Ruthenian dialect or language – a term used by some scholars as designation for northern varieties, that gave rise to modern Belarusian language,[26] that is also designated as White Ruthenian.[27]

- South Ruthenian dialect or language – a term used by some scholars as designation for southern varieties, that gave rise to modern Ukrainian language,[28][29] that is also designated as Red Ruthenian.

Terminological dichotomy, embodied in parallel uses of various endoymic and exonymic terms, resulted in a vast variety of ambiguous, overlapping or even contrary meanings, that were applied to particular terms by different scholars. That complex situation is addressed by most English and other western scholars by preferring the exonymic Ruthenian designations.[30][31][23]

Periodization

Daniel Bunčić suggested a periodization of the literary language into:[32]

- Early Ruthenian, dating from the separation of Lithuanian and Muscovite chancery languages (15th century) to the early 16th century

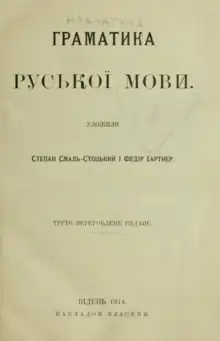

- High Ruthenian, from Francysk Skaryna (fl. 1517–25), to Ivan Uzhevych (Hramatyka slovenskaia, 1643, 1645)

- Late Ruthenian, from 1648 to the establishment of the Ukrainian and Belarusian standard languages at the end of the 18th century

George Shevelov gives a chronology for Ukrainian based on the character of contemporary written sources, ultimately reflecting socio-historical developments: Proto-Ukrainian, up to the mid-11th century, Old Ukrainian, to the 14th c., Early Middle Ukrainian, to the mid-16th c., Middle Ukrainian, to the early 18th c., Late Middle Ukrainian, rest of the 18th c., and Modern Ukrainian.[33]

See also

References

- 1 2 Ж. Некрашевич-Короткая. Лингвонимы восточнославянского культурного региона (историчесикий обзор) [Lingvonyms of the East Slavic Cultural Region (Historical Review)] (in Russian) // Исследование славянских языков и литератур в высшей школе: достижения и перспективы: Информационные материалы и тезисы докладов международной научной конференции [Research on Slavic Languages and Literature in Higher Education: Achievements and Prospects: Information and Abstracts of the International Scientific Conference]/ Под ред. В. П. Гудкова, А. Г. Машковой, С. С. Скорвида. — М., 2003. — С. 150 — 317 с.

- 1 2 Начальный этап формирования русского национального языка [The initial stage of the formation of the Russian national language], Ленинград 1962, p. 221

- ↑ Magocsi, Paul Robert (1996). A History of Ukraine. University of Toronto Press. pp. 131, 140. ISBN 0802008305.

- 1 2 Kamusella, Tomasz (2021). Politics and the Slavic Languages. Routledge. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-367-56984-6.

- ↑ Frick 1985, p. 25-52.

- ↑ Pugh 1985, p. 53-60.

- 1 2 Bunčić 2015, p. 276-289.

- ↑ Moser 2017, p. 119-135.

- ↑ Moser 2018, p. 87-104.

- ↑ "Ukrainian Language". Britannica.com.

- ↑

"Statut Velikogo knyazhestva Litovskogo" Статут Великого княжества Литовского [Statute of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (Section 4 Article 1)]. История Беларуси IX-XVIII веков. Первоисточники.. 1588. Archived from the original on 2018-06-29. Retrieved 2019-10-25.

А писаръ земъский маеть по-руску литерами и словы рускими вси листы, выписы и позвы писати, а не иншимъ езыкомъ и словы.

- ↑ Verkholantsev 2008, p. 1-17.

- ↑ Мозер 2002, p. 221-260.

- 1 2 Danylenko 2006a, p. 80-115.

- ↑ Danylenko 2006b, p. 97–121.

- ↑ Verkholantsev 2008, p. 1.

- ↑ Danylenko 2006b, p. 98-100, 103–104.

- ↑ Danylenko 2006b, p. 100, 102.

- ↑ Waring 1980, p. 129-147.

- ↑ Cited in Улащик Н. Введение в белорусско-литовское летописание. — М., 1980.

- ↑ Elana Goldberg Shohamy and Monica Barni, Linguistic Landscape in the City (Multilingual Matters, 2010: ISBN 1847692974), p. 139: "[The Grand Duchy of Lithuania] adopted as its official language the literary version of Ruthenian, written in Cyrillic and also known as Chancery Slavonic"; Virgil Krapauskas, Nationalism and Historiography: The Case of Nineteenth-Century Lithuanian Historicism (East European Monographs, 2000: ISBN 0880334576), p. 26: "By the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries Chancery Slavonic dominated the written state language in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania"; Timothy Snyder, The Reconstruction Of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999 (Yale University Press, 2004: ISBN 030010586X), p. 18: "Local recensions of Church Slavonic, introduced by Orthodox churchmen from more southerly lands, provided the basis for Chancery Slavonic, the court language of the Grand Duchy."

- ↑ Danylenko 2006a, p. 82-83.

- 1 2 Danylenko 2006b, p. 101-102.

- ↑ Shevelov 1979, p. 577.

- ↑ Pugh 1996, p. 31.

- ↑ Borzecki 1996, p. 23.

- ↑ Borzecki 1996, p. 40.

- ↑ Brock 1972, p. 166-171.

- ↑ Struminskyj 1984, p. 33.

- ↑ Leeming 1974, p. 126.

- ↑ Danylenko 2006a, p. 82-83, 110.

- ↑ Bunčić 2015, p. 277.

- ↑ Shevelov 1979, p. 40–41, 54–55.

Literature

- Borzecki, Jerzy (1996). Concepts of Belarus until 1918 (PDF). Toronto: University of Toronto.

- Brock, Peter (1972). "Ivan Vahylevych (1811–1866) and the Ukrainian National Identity". Canadian Slavonic Papers. 14 (2): 153–190. doi:10.1080/00085006.1972.11091271. JSTOR 40866428.

- Brogi Bercoff, Giovanna (1995). "Plurilinguism in Eastern Slavic Culture of the 17th Century: The case of Simeon Polockij". Slavia: Časopis pro slovanskou filologii. 64: 3–14.

- Bunčić, Daniel (2006). Die ruthenische Schriftsprache bei Ivan Uževyč unter besonderer Berücksichtigung seines Gesprächsbuchs Rozmova/Besěda: Mit Wörterverzeichnis und Indizes zu seinem ruthenischen und kirchenslavischen Gesamtwerk. München: Verlag Otto Sagner.

- Bunčić, Daniel (2015). "On the dialectal basis of the Ruthenian literary language" (PDF). Die Welt der Slaven. 60 (2): 276–289.

- Danylenko, Andrii (2004). "The name Rus': In search of a new dimension". Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas. 52 (1): 1–32.

- Danylenko, Andrii (2006a). "Prostaja Mova, Kitab, and Polissian Standard". Die Welt der Slave. 51 (1): 80–115.

- Danylenko, Andrii (2006b). "On the Name(s) of the Prostaja Mova in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth". Studia Slavica. 51 (1/2): 97–121. doi:10.1556/SSlav.51.2006.1-2.6.

- Dingley, James (1972). "The Two Versions of the Gramatyka Slovenskaja of Ivan Uževič" (PDF). The Journal of Byelorussian Studies. 2 (4): 369–384.

- Frick, David A. (1985). "Meletij Smotryc'kyj and the Ruthenian Language Question". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 9 (1/2): 25–52. JSTOR 41036131.

- Leeming, Harry (1974). "The Language of the Kucieina New Testament and Psalter of 1652" (PDF). The Journal of Byelorussian Studies. 3 (2): 123–144.

- Мозер, Михаэль А. (2002). "Что такое «простая мова»?". Studia Slavica. 47 (3/4): 221–260. doi:10.1556/SSlav.47.2002.3-4.1.

- Moser, Michael A. (2005). "Mittelruthenisch (Mittelweißrussisch und Mittelukrainisch): Ein Überblick". Studia Slavica. 50 (1/2): 125–142. doi:10.1556/SSlav.50.2005.1-2.11.

- Moser, Michael A. (2017). "Too Close to the West? The Ruthenian Language of the Instruction of 1609". Ukraine and Europe: Cultural Encounters and Negotiations. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 119–135. ISBN 9781487500900.

- Moser, Michael A. (2018). "The Fate of the Ruthenian or Little Russian (Ukrainian) Language in Austrian Galicia (1772-1867)". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 35 (2017–2018) (1/4): 87–104. JSTOR 44983536.

- Pivtorak, Hryhorij. “Do pytannja pro ukrajins’ko-bilorus’ku vzajemodiju donacional’noho periodu (dosjahnennja, zavdannja i perspektyvy doslidžen’)”. In: Movoznavstvo 1978.3 (69), p. 31–40.

- Pugh, Stefan M. (1985). "The Ruthenian Language of Meletij Smotryc'kyj: Phonology". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 9 (1/2): 53–60. JSTOR 41036132.

- Pugh, Stefan M. (1996). Testament to Ruthenian: A Linguistic Analysis of the Smotryc'kyj Variant. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780916458751.

- Shevelov, George Y. (1974). "Belorussian versus Ukrainian: Delimitation of Texts before A.D. 1569" (PDF). The Journal of Byelorussian Studies. 3 (2): 145–156.

- Shevelov, George Y. (1979). A Historical Phonology of the Ukrainian Language. Heidelberg: Carl Winter. ISBN 9783533027867.

- Stang, Christian S. (1935). Die Westrussische Kanzleisprache des Grossfürstentums Litauen. Oslo: Dybwad.

- Struminskyj, Bohdan (1984). "The language question in the Ukrainian lands before the nineteenth century". Aspects of the Slavic language question. Vol. 2. New Haven: Yale Concilium on International and Area Studies. pp. 9–47. ISBN 9780936586045.

- Verkholantsev, Julia (2008). Ruthenica Bohemica: Ruthenian Translations from Czech in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Poland. Berlin: LIT. ISBN 9783825804657.

- Waring, Alan G. (1980). "The Influence of Non-Linguistic Factors on the Rise and Fall of the Old Byelorussian Literary Language" (PDF). The Journal of Byelorussian Studies. 4 (3/4): 129–147.

External links

- "Hrodna town books language problems in Early Modern Times" by Jury Hardziejeŭ

- Zinkevičius, Zigmas. "Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės kanceliarinės slavų kalbos termino nusakymo problema". viduramziu.istorija.net (in Lithuanian). Archived from the original on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 2 August 2018.