| Charles Edward | |

|---|---|

| Duke of Albany | |

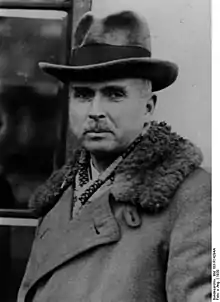

Charles Edward in 1933, as SA-Gruppenführer | |

| Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha | |

| Reign | 30 July 1900 – 14 November 1918 |

| Predecessor | Alfred |

| Born | 19 July 1884 Surrey, England |

| Died | 6 March 1954 (aged 69) Coburg, West Germany |

| Spouse | Princess Victoria Adelaide of Schleswig-Holstein |

| Issue |

|

| House | Saxe-Coburg and Gotha |

| Father | Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany |

| Mother | Princess Helena of Waldeck and Pyrmont |

| Military career | |

| Service/ | |

Charles Edward (Leopold Charles Edward George Albert, German: Leopold Carl Eduard Georg Albert[note 1]; 19 July 1884 – 6 March 1954) was the last sovereign duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, reigning from 1900 until 1918. His father, Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany, was a son of the British Queen Victoria and Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Having suffered from haemophilia, Leopold died before Charles's Edward birth. Charles Edward's mother was the German-born Princess Helen of Waldeck and Pyrmont. He was brought up as a British prince. He was a sickly child who developed a close relationship with Victoria and his only sibling, Alice. He was privately educated, lastly at Eton College.

In 1899, Charles Edward was selected to succeed to the throne of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, a state in the German Empire, because he was deemed young enough to be reeducated as a German. He moved to Germany at the age of 15. Between 1899 and 1905 he was put through various forms of education guided by his cousin the German emperor, Wilhelm II. He ascended the ducal throne on 30 July 1900 but initially reigned through a regency. In 1905 he adopted the political powers associated with the role. That year, Wilhelm arranged Charles Edward's marriage to Princess Victoria Adelaide of Schleswig-Holstein. The couple had five children, born from 1906 to 1918, and became the maternal grandparents of King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden.

Charles Edward was a conservative ruler with an interest in art and technology. He tried to emphasise his loyalty to Germany through a variety of symbolic gestures but his continued closeness to Great Britain was off-putting to both his local subjects and the German elite. During the First World War, Charles Edward chose to support the German Empire. Being physically disabled, he participated in the German Army in non-combat positions. The German Revolution deposed Charles Edward like the other German monarchs. He also lost his British titles due to his betrayal of the United Kingdom.

During the 1920s, Charles Edward became a moral and financial supporter of the violent far-right in Germany. He was given various positions in the Nazi regime including leader of the German Red Cross. He was involved in promoting eugenicist ideas which provided a basis for the murder of many disabled people. He acted as an informal diplomat for the regime and was especially involved in attempting to shift opinion among the British elite in a more pro-German direction. His attitudes became more pro-Nazi during World War II though it is unclear how much of a political role he played. After the war he was interned for a period and was given a minor conviction by a denazification court. He died of cancer in 1954.

Early life in Britain

Birth and family background

On 19 July 1884, at Claremont House near Esher, Surrey, Princess Helena, Duchess of Albany, gave birth to a son, Prince Charles Edward. His father was Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany, the youngest son of the reigning British monarch, Queen Victoria.[2] Leopold, who suffered from haemophilia, had died after slipping and hitting his head months before Charles Edward's birth.[3] Because a boy cannot inherit the condition from his father, Charles Edward was not affected by haemophilia.[4] Charles Edward succeeded to Leopold's titles at birth and was styled His Royal Highness the Duke of Albany. In addition to being Duke of Albany, he was also Earl of Clarence and Baron Arklow.[5] After falling ill, the infant was baptised privately at Claremont on 4 August 1884. He was publicly baptised in St George's Church, Esher on 4 December 1884.[6]

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries the British royal family had developed close familial relationships with continental protestant and particularly German aristocrats.[1] Queen Victoria's immediate family belonged to the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha; her deceased husband, Prince Albert, was the younger brother of the childless Duke Ernest II[7] who governed the Duchy of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, one of the states in the federalised German Empire.[8] Victoria and Albert's eldest daughter, Victoria, was the mother of Wilhelm II, who reigned as the German emperor from 1888. Their eldest son, Prince Albert Edward, was the heir apparent to the British throne. Thus it was Victoria and Albert's second son, Prince Alfred, who succeeded his uncle Ernest II in 1893.[7]

Childhood

Charles Edward was brought up as a prince of the United Kingdom for his first 15 years.[2] He, his mother, and his older sister, Princess Alice of Albany, lived with members of the wider royal family in proximity to Queen Victoria.[8] Charles Edward was described as Victoria's favourite grandchild.[9] Princess Helena, who was the daughter of the ruling prince of Waldeck and Pyrmont, George Victor, and sister of the Dutch Queen Emma, infrequently took her children to visit her relatives in Germany and the Netherlands.[9] Charles Edward's childhood nanny referred to him as "delicate and sensitive, nervous and tiring". Medical experts consulted by the royal family believed that he had been permanently harmed by the grief his widowed mother had suffered during her pregnancy.[9] Being an intensely anxious child, he often looked to Alice for support, a habit that continued throughout his adulthood.[1] The siblings were nicknamed "Siamese twins".[9]

No record exists of Charles Edward's own childhood memories but Alice fondly recalled this period of their lives. Charles Edward developed an interest in military and royal occasions at a young age. He was given his first ceremonial position in the British Army as a child. Shortly before his 13th birthday, Charles Edward participated in a parade for the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria. The boy climbed on the roof of Buckingham Palace to see the assembled crowds before the event and was described in contemporary press reports as being the most well-received participant. Charles Edward and his sister often visited Balmoral Castle where courtiers and sometimes their grandmother prepared them for their future positions. Victoria enjoyed the children acting out dramatical scenes which reflected the religious values she wanted to inculcate into them. Children's author and family friend Lewis Carroll described Charles Edward as a "perfect little prince" who was well-trained in court etiquette and ceremony.[9]

Charles Edward attended two prep schools, firstly Sandroyd School in Surrey[note 2] and later Park Hill School in Lyndhurst. In 1898 he enrolled at Eton College and his mother hoped he would eventually go on to Oxford University.[4] Press reports sometimes accused him of behaving self-importantly at school.[9] He was happy at Eton and looked back nostalgically at his time at that school throughout his life.[4] He was not expected to grow up to be a particularly prominent person.[1]

Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

Accession and education in Germany

In 1899, the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, influenced by Queen Victoria's grandson Emperor Wilhelm II, decided on how to deal with the succession of Duke Alfred, who was in ill health. Duke Alfred's only son, Prince Alfred, had died in February 1899.[2][7] Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn, Victoria and Albert's third son, was initially heir presumptive but sections of the German press objected to a foreigner taking the throne and Wilhelm II opposed a man who had served in the British army becoming ruler of a German state.[1][7] His son, Prince Arthur of Connaught, had been at Eton with Charles Edward. Wilhelm II demanded a German education for the boy, but this was unacceptable to the Duke of Connaught. Thus both Charles Edward's uncle and cousin renounced their claims to the duchy, leaving Charles Edward next in line.[7]

Charles Edward's young age (he was fourteen at the time), his lack of a father and his German mother meant that he was deemed able to assimilate into German society in a way an older man would not be. The local newspaper in Coburg praised this decision.[10] There was significant public interest in Germany in what happened to Charles Edward.[8][10] According to historian Alan R. Rushton some Germans felt "it was now important for the English boy to become a German man and leader of his adopted land".[8] He was named heir under family pressure.[4] There were reports in the American press that the younger Arthur had beaten Charles Edward up or threatened to do so if he did not accept the position.[11][12] Charles Edward did not appear pleased with this decision. Rushton quoted him as saying: "I've got to go and be a beastly German prince." But the adults around him seem to have encouraged him to embrace his new role. His sister remembered their mother saying that "I have always tried to bring up Charlie as a good Englishman, and now I have to turn him into a good German", while Field Marshal Frederick Roberts told him to "Try to be a good German!".[8]

Charles Edward moved to Germany with his mother and sister when he was fifteen. He spoke little German. Duke Alfred wanted to separate Charles Edward from Helena so she took him to stay with her brother-in-law King William II of Württemberg and found him a tutor.[4] Later, Emperor Wilhelm organised an education plan for Charles Edward.[2][4] According to historian Karina Urbach, Wilhelm wanted to turn his young cousin into a "Prussian officer".[1] He invited the family to live in Potsdam, the government district of Berlin, while Charles Edward attended the Preußische Hauptkadettenanstalt (Prussian Central Cadet Institute) at Lichterfelde and studied government management at Prussian government ministries. He was made a lieutenant of cavalry on his 16th birthday in 1900[8] and joined the 1. Garderegiment zu Fuß (1st Foot Guards) at Potsdam.[2][7] He also attended Bonn University.[4] He studied law but was not a particularly academic young man and mainly enjoyed participating in the Corps Borussia Bonn.[1]

Charles Edward tried his best to assimilate while maintaining some links with Britain such as participating in Anglican religious services.[8] Urbach suggested he learnt the language quickly and commented that his "German essays [at the military academy] were soon receiving higher marks than his English ones".[1] However various statements made by Charles Edward during this period suggest he was homesick and unhappy with his situation.[1][8] Charles Edward inherited the ducal throne of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha at the age of sixteen when his uncle Alfred died at the age of 55 in July 1900.[2][7] Charles Edward cried at the funeral—a reaction that Urbach interpreted as an expression of fear about his future rather than grief for an uncle he had relatively little relationship with.[1] In 1901 Charles Edward attended Queen Victoria's funeral wearing the uniform of the Prussian Hussars.[9] His eldest paternal uncle, who succeeded Queen Victoria as King Edward VII, made Charles Edward a Knight of the Garter on 15 July 1902, just before the young duke's 18th birthday.[13] His entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography described him as a "conscientious young man with a taste for the arts and music" who became popular in Coburg during this period.[4] Urbach described him as "immature".[1] According to a contemporary news report he was fond of "sport and adventure".[12] A 1905 article in the London and China Express, a British newspaper focused on foreign affairs, commented that:

All the [German] newspapers sing the praises of the young Duke and describe his sympathetic character and bearing. Above all they are never tired of emphasising how German he has become, how he has completely forgotten the English training of his early youth, identifying himself in every way with the interests of Germany.[14]

Wilhelm II took such interest in Charles Edward's assimilation into German society that Charles Edward was known in the Imperial Court as "the Emperor's seventh son".[15] Charles Edward, with his mother and sister, spent a lot of their spare time in the German court in Berlin, where they were treated as members of the emperor's family. The women got on well with Empress Augusta Victoria, while Wilhelm became something of a substitute father for Charles Edward.[8] Wilhelm saw Charles Edward as impressionable[7] and introduced him to his own worldview, including antisemitism, German nationalism and hostility to the Reichstag (parliament).[8][16] During a political scandal in 1908 there were allegations of Charles Edward engaging in homosexual activity with Wilhelm.[8] Charles Edward often did not enjoy his time in Berlin where the emperor seemed to become resentful of him and frequently bullied him.[4] A 1905 report by the court chaplain commented that one evening Wilhelm had given the young man a "proper beating up".[8]

Peacetime reign

From 1900 to 1905, Charles Edward reigned through the regency of Ernst, Hereditary Prince of Hohenlohe-Langenburg, the husband of Duke Alfred's third daughter Alexandra.[4] Charles Edward assumed full constitutional powers upon coming of age on 19 July 1905.[2] At his investiture he read a speech promising his allegiance to the German Empire and was cheered by onlookers after publicly sampling local food. Privately he thought Saxe-Coburg and Gotha were beautiful and looked forward to governing there.[2] He joined various patriotic groups to emphasise his loyalties. However, according to Urbach, Charles Edward lacked popularity. This was especially true in Gotha, an impoverished town with left-wing sympathies; to them he seemed absolutist. In Coburg, a wealthy and conservative town known for its intense nationalism, people were generally more sympathetic to Charles Edward but disliked a sense of foreignness they detected about him. For instance, he continued to have an English accent and faced criticism for keeping Scottish Terrier dogs and for always appearing in public with a police guard.[10]

Friedrich Facius described Charles Edward as initially a liberal who shifted in a more authoritarian direction. He was supportive to the emperor and understood the government institutions.[2] According to Rushton, Charles Edward's political worldview was "conservative and nationalistic", reflecting what had been inculcated into him by Wilhelm II. He largely left governing to the cabinet he appointed. They used the motto "Everything as it has been" to describe their approach. Charles Edward frequently visited local events. He was interested in new forms of transportation, especially automobiles and airships. He invested in the creation of a new airship docking bay in Gotha, a decision that appeared commercially sensible.[8] He enthusiastically supported the court theatres in both towns and organised the restoration of the Veste Coburg which was conducted between 1908 and 1924.[2] In 1910 he joined the "Reich Association against Social Democracy", a pro-monarchist political organisation.[9]

Charles Edward also became the main local landowner and had an annual income of about 2.5 million marks. He lived in both Coburg and Gotha for several months each year, as well as visiting his mountain or hunting lodges. He usually worked in the morning and spent the afternoon on leisure activities such as hiking. Recreation took up the bulk of his time and he was frequently abroad or in other parts of Germany. Charles Edward struggled with social interaction, especially with those that were different from him. He stopped local people from entering the countryside surrounding his castles, adding to his seclusion.[8] He tended to spend much of his time in the company of courtiers that regularly offered him praise. Charles Edward frequently tried to emphasise his loyalty to Germany through displays of cultural traditions such as Christmas festivities and folk costumes.[9] Historian Juliet Nicolson has described these years as "the perfect summer"—a time when privileged people enjoyed their wealth and social advantages in denial of the threats to their way of life that were starting to appear in politics and organised labour. Rushton commented that

Charles Edward had every reason to be happy with his life: a growing healthy family, minimal professional duties, the opportunity to live very well and associate with his friends and relatives at the upper echelons of society in Europe... As 1914 began, Charles Edward had not the slightest clue that the golden age of the European nobles was coming to a climax. He continued to hunt and travel, acting as an absolute sovereign... His life as a monarch seemed to exist in a parallel world that had little in common with the majority of his subjects.[8]

Charles Edward continued to have a good relationship with the British royal family and regularly visited the United Kingdom.[4][8] In 1910 the Daily Mirror published a photograph of him wearing the uniform of the Seaforth Highlanders, a British army regiment of which he was colonel-in-chief, at an inspection of its veterans.[17] Members of the German political elite were often irritated by his continued close relationship with Great Britain. His decision to wear the uniform of his British regiment at the funeral of Edward VII in 1910 caused particular annoyance. Officials at the German Embassy in London were suspicious of his frequent visits to the United Kingdom. In private he frequently engaged in British activities even while in Germany. Charles Edward and his wife performed Scottish country dances to bagpipes. His immediate family used English language nicknames. He generally tried to stay out of politics, especially diplomatic issues between Great Britain and Germany, which led to him receiving additional criticism. German historian Hubertus Büschel believed that Charles Edward's attempts to come across as German during this period were likely an effort to please Wilhelm II and nationalist circles in Germany rather than an expression of his own identity.[9]

Marriage and children

Wilhelm II chose his niece Princess Victoria Adelaide of Schleswig-Holstein as the bride of Charles Edward. She was believed to be well adjusted and loyal to Wilhelm's royal house. Charles Edward was told to propose to her and obliged.[1] They married on 11 October 1905, at Glücksburg Castle, Schleswig-Holstein, and had five children.[2] Victoria Adelaide was described in her grandson's memoirs as the leading part in the marriage and Charles Edward would initially come to her for advice.[18] His entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography comments that they were happy,[4] but Urbach indicates otherwise.[1] They had five children: Prince Johann Leopold (1906—1972), Princess Sibylla (1908—1972), Prince Hubertus (1909—1943), Princess Caroline Mathilde (1912—1983), and Prince Friedrich Josias (1918—1998).[19]

As was the norm for upper-class households at the time, caring for the children was largely delegated to the domestic servants.[8] The family mainly spoke English at home, though the children learnt to speak German fluently. Hubertus, Charles Edward's second son, was the favourite child.[20] A profile of the family published in the British newspaper The Sphere in 1914 described Charles Edward's sons and daughters as "bright, happy children who lead a natural life, spending a great deal of their time in the open air in the fine grounds of their castle" and mentioned they enjoyed various sports.[21]

Later, according to Urbach, the children lived in fear of their father, who ran his family "like a military unit". Charles Edward's younger daughter, Princess Caroline Mathilde, claimed that her father had sexually abused her. The allegation was backed by one of her brothers. When they grew up, Charles Edward's children were often a disappointment to him in their choice of romantic relationships at a time when he was trying to use strategic marriages to improve the diminished reputation of his royal house.[1]

First World War

The First World War caused a conflict of loyalties for Charles Edward, but he decided to support the German Empire.[2][7] He was in England at the time of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand to receive an honorary degree as Doctor of Civil Laws from Oxford University.[8] He told his sister that he wanted to fight for Great Britain but felt obligated to return to his duchy, where public opinion began to turn against the Duke due to his British origins.[4] He returned to Germany on 9 July.[8] After the war he would describe the events of 1914, in a letter to his sister, as the end of his personal "happiness".[8]

At the start of the war, he publicly denounced Britain accusing it of attacking Germany and renounced his position as Colonel-in-chief of the Seaforth Highlanders.[1] He broke off relations with his family at the British and Belgian courts; this did not suffice to overcome doubts about his loyalties in Germany.[2][7] His attitudes would become more sincerely pro-German as the war years progressed.[4] Incapable of active combat due to a lame leg,[4] he provided non-combat support to the army corps from his territories. He initially participated in the German invasion of Belgium but was soon moved to the Eastern Front. Charles Edward received an Iron Cross "for bravery" at the end of 1914.[8] He visited both the Western and Eastern Fronts numerous times, though he never held a command. Soldiers from his duchies were awarded the Carl-Eduard-Kriegskreuz (Carl Eduard War Cross).[2][7] According to Urbach, Charles Edward "was more or a less a chocolate soldier, who spent most of his time dining at various casinos behind the front and visiting 'his' Coburg troops".[1]

In 1917, a law change in Coburg effectively banned Charles Edward's British relatives from succeeding him and that same year the Gotha G.V bomber, which had been built in Gotha, was used to attack London.[7] In Britain, he was denounced as a traitor.[4] He was one of a group of noblemen living in Germany and Austria who held British titles but sided with the Central Powers—a group frequently identified in the British press as the "traitor peers".[22][23][24] For instance soon after the conclusion of the war The Sunday Post published a report on the "traitor dukes" which included a negative and personally vitriolic profile of Charles Edward's life that called his role in the war "one of the blackest chapters in his ignominious career".[25] In 1915, King George V, his cousin, ordered his name removed from the register of the Most Noble Order of the Garter.[13] The Titles Deprivation Act 1917 began the process of removing his British titles.[26] Urbach observed that Charles Edward did not seem to care that his behaviour might have put his mother, who was living in London under the protection of Queen Mary, at risk of reprisals.[1]

Charles Edward worked for military staff on the Western Front in the later war years. He contributed 250,000 marks out of his personal wealth to financial support for the families of dead soldiers from his territories. A report published in The Times a few years after the war commented that he had often provided assistance to British prisoners of war—a decision which it described as a sign of his "consideration and humanity". Charles Edward was alarmed by the murder of the Russian royal family in 1918; Empress Alexandra was one of his cousins. He worried that the same thing would happen to his own family. Rushton wrote that it was the beginning of the fear of communism that would define his political activities in years to come.[8] He joined the League of the Emperor's Loyalists, an organisation of supporters of the German emperor, though he preferred German general and de facto military dictator Paul von Hindenburg as a leader.[1] Büschel argued that Charles Edward's First World War experiences were a "school for nationalism, violence, and antisemitism".[27]

The war placed severe burdens on the German population and after the middle of 1918 the empire's military situation collapsed. By late in the year an armistice was signed and a revolution broke out in Germany.[8] On the morning of 9 November 1918, the Workers' and Soldiers' Council of Gotha declared Charles Edward deposed. On 11 November, his abdication was demanded in Coburg. Only on 14 November, later than most other ruling princes, did he formally announce that he had "ceased to rule" in both Gotha and Coburg. He did not explicitly renounce his throne.[2] According to Rushton the slowness of Charles Edward's abdication was due to paranoia that he would be killed, although the transition of power in Coburg was quite calm and orderly compared to some parts of Germany. The German nobility were not physically attacked during the revolution, but the situation was deeply frightening and a cause of much resentment for them.[8]

Far-right advocate

Urbach wrote that Charles Edward was not popular and still seen by some as English. By the end of the war, the left-wing, anti-royalist parts of the local press had been nicknaming him "Mr Albany" in a reference to his foreign origins. But he could still live in Coburg fairly contentedly.[1] According to Rushton he retained much of his prestige and was often still seen by his former subjects as essentially still duke.[8] In 1919 he also lost his British titles, though some personal sympathy remained for him among the political establishment in the United Kingdom due to the way German nationality had been forced on him as a teenager.[4] He visited his mother and sister in London in 1921 but was generally unwanted in Britain.[1]

In 1919, his properties and collections in Coburg were transferred to the Coburg State Foundation, a foundation that still exists today. A similar solution for Gotha took longer, and only after legal struggles with the Free State of Thuringia was it set up in 1928–34. The Gotha foundation was expropriated by the Soviet authorities after 1945.[2] After 1919, the family retained Schloss Callenberg, some other properties (including those in Austria), and a right to live at Veste Coburg. It also received substantial financial compensation for lost possessions. Some additional real estate in Thuringia was restored to the ducal family in 1925.[7] When Charles Edward's mother died in 1922 the British government stopped him from inheriting Claremont House.[1]

Politically, in the post-WW1 period, Charles Edward aimed for the restoration of the monarchy and supported the nationalistic-conservative, völkisch right.[2] He was nostalgic for aspects of pre-war Germany, especially its militarism, and was frightened of communism. Urbach also suggested he had an obsession with masculine physical strength which stemmed from his lack of it.[1] Charles Edward became associated with various right-wing paramilitary and political organisations.[2] Rushton wrote that he "became a member and patron of the paramilitary group Coburg Einwohnerwehr, the Bund Wiking and the veterans group Der Stahlhelm".[8] The Bund had previously been the Organisation Consul in the early 1920s—a group which Charles Edward also funded and participated in and which was involved in politically motivated murders of politicians Karl Gareis and Walther Rathenau. Urbach comments that "Though Carl Eduard did not himself murder, he financed murderers".[1] He hid Hermann Ehrhardt in one of his castles with a store of weapons after Ehrhardt participated in the Kapp Putsch against the government.[8]

Charles Edward also funded various anti-semitic nationalist groups. In 1922 Charles Edward was invited to a traditional event where the best performing student leaving a local gymnasium[note 3] could make a speech. The schoolboy chosen that year was a Jewish young man called Hans Morgenthau. Charles Edward expressed his disapproval by turning his back to Morgenthau and holding his nose throughout the speech. On 14 October 1922 the Nazi Party participated in a nationalist event called the German Day in Coburg which involved a significant amount of violence. That evening Charles Edward attended a meal run by the party where Adolf Hitler spoke. The next day he shook hands with Hitler, becoming the first nobleman to publicly support him.[8] From 1929, he provided financial support to the Nazi Party.[27] He was attracted by the party's militarism and anti-communism.[4]

Charles Edward was a useful ally for the Nazis in the period before they gained power, with extensive links in Franconia and across Germany. In 1929 Charles Edward's support contributed to Coburg becoming the first town in Germany to elect a Nazi Party council. In 1932 Charles Edward took part in the creation of the Harzburg Front, through which the German National People's Party and other groups with similar views became associated with the Nazi Party. He also publicly called on voters to support Hitler in the presidential election of 1932. A few months later, Charles Edward's daughter Sibylla married Prince Gustaf Adolf, Duke of Västerbotten, the eldest son of the Crown Prince of Sweden and second-in-line to the Swedish throne. The marriage meant that Sibylla would, in the normal course, become Queen of Sweden. He used the event as a public display of his ideology and to improve the damaged prestige of the house of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha.[1]

Following the election of the Nazi Party locally in 1929, the Jewish population of Coburg experienced growing amounts of physical abuse and discrimination. Rushton writes that Charles Edward's publicly expressed beliefs and financial support contributed to shaping attitudes in Coburg, broader German opinion and the oppression of local Jewish people. It was widely known that Charles Edward and his wife were anti-semitic. According to Rushton, Charles Edward would have been aware of the violent behaviour of the movements he was involved in but never objected. World War I had convinced him of the merits of political violence.[8]

Nazi party figure

Charles Edward formally joined the Nazi Party in March 1933; he also became an Obergruppenführer in the SA.[7] According to Urbach he became a "highly honoured" member of the party, appearing in photographs with its senior members and setting up an office in Berlin which he could use to form relationships. She wrote that he was proud of his Nazi Party membership and that the SA uniform allowed him to feel more like his pre-war self. Urbach also wrote that the regime allowed him to use a uniform for a Wehrmacht general but she does not specify when.[1] Charles Edward was made president of the National Socialist Automobile Association, an organisation which provided vehicles for the German state, including those used to carry out the Holocaust.[27] From 1936 to 1945, he served as a member of the Reichstag, representing the Nazi Party.[7]

German Red Cross and eugenics

In December 1933 Charles Edward was appointed head of the Deutsches Rotes Kreuz (German Red Cross). Hitler approved the appointment because he knew Charles Edward well. He believed that Charles Edward was a supporter of the Nazis' ideas relating to race and eugenics. The organisation was quickly made to conform with the government's goals. Rushton comments that "Two years after the founding of the new regime, the DRK [German Red Cross] was remodeled into a paramilitary organization with the goal of providing support for soldiers in a time of conflict". In 1937 Ernst-Robert Grawitz was made deputy leader in order to increase the organisation's links with the SS and Charles Edward was made "an officer of the chancellery of the Fuhrer", giving him access to private information on government business. The senior roles in the organisation were increasingly filled by Nazi Party members and members of the organisation were taught that "Jews, Slavs, chronically ill, handicapped... were nothing more than worthless".[8] American historian Jonathan Petropoulos wrote of the German Red Cross's role in the regime that

The German Red Cross, which Heinrich Himmler's SS infiltrated, helped conceal the true horrors of the concentration camps and psychiatric institutions, the latter serving as the sites for the murderous T-4 program that targeted the mentally and physically disabled. The duke [Charles Edward] used his venerable name and excellent manners to assist the Nazis in their propaganda campaign. He helped deceive the International Red Cross and its president, Carl Jacob Burckhardt, and this included orchestrating Burckhardt's 1935 inspection tour, during which he visited Dachau.[27]

Charles Edward was placed on the governing body of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in 1933 and remained in that position until 1945. He was secretary of the executive board from 1934 to 1937. In those positions he was involved in promoting eugenicist ideas to the German public, particularly to individuals with power in German society. The German government organised multiple schemes to murder disabled people later in the regime. The first scheme, targeted at children, ran from 1939 to the end of the war and killed 5,300 disabled children. The second scheme, which ran from late 1939 to mid-1941, killed more than 70,000 disabled people at six killing centres in Germany and Austria mainly through gassing. Grawitz was heavily involved in this. A third scheme in the later war years used more covert methods, to a large extent deliberate starvation. It is estimated to have killed between 100,000 and 180,000 people.[8]

Most evidence which could clarify the level of involvement of the German Red Cross in these events was destroyed accidentally or deliberately by the end of the war. While most transportation of victims was done by a proxy organisation created for that purpose, the German Red Cross were involved in transporting some. Many of the nurses who were involved in murdering disabled people were employees of the German Red Cross who had been indoctrinated by the organisation. Rushton believed that Charles Edward would have known about these schemes. Princess Marie Karoline, a member of Charles Edward's extended family, was murdered by the programme in 1941—although upper-class disabled people generally had a degree of protection due to their use of private healthcare and their families' political connections. According to Rushton, Charles Edward had not intervened because "he had not been concerned that anything would happen to her". He received a letter of condolence claiming that she had died of natural causes, which he did not believe. Unusually for a man who rarely missed family events, he did not attend the funeral.[8]

Unofficial diplomat

The Nazi regime made significant use of Charles Edward as an informal diplomat.[1] In 1934, Charles Edward visited Japan, where he attended a conference on the protection of civilians during war, and delivered Hitler's birthday greeting to Emperor Hirohito.[7] He hosted an international press tour associated with the Duke and Duchess of Windsor's visit to Germany in 1937.[28] He visited Italy in 1938, meeting King Victor Emmanuel III and dictator Benito Mussolini. He went on a trip to Poland meeting Polish officials only a few months before the country was invaded by Germany and the Soviet Union.[29] In 1940, Charles Edward travelled via Moscow and Japan to the US, where he met President Roosevelt at the White House. In 1943, at Hitler's behest, Charles Edward asked the International Red Cross to investigate the Katyn massacre.[7]

Charles Edward was particularly significant to Nazi attempts to cultivate pro-German sentiments among the British aristocracy.[1] By 1936, he had agreed to be a spy for Hitler while attending the funeral of his first cousin King George V at Sandringham.[31] He attended George V's funeral as Hitler's representative, in an SA uniform, complete with a metal helmet.[32] He was president of the German version of the Anglo-German fellowship[1] and lobbied figures believed to be pro-German.[4] He was made head of the organisation after the regime decided that it was not pro-Nazi enough.[1] He also visited veterans meetings in the United Kingdom.[7] Charles Edward's Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry argued that his advocacy had little success, and that he failed to understand the degree to which the people he had grown up around now saw him as a foreigner.[4] In contrast, Urbach argued in her 2015 book that the strains experienced by British society during the interwar period had a radicalising effect on sections of the British elite and that there was significant sympathy for fascism, albeit discomfort with Nazism, in particular among the aristocracy. She wrote that Charles Edward reintegrated himself into aristocratic social life in Britain with the help of his sister and influenced prominent aristocrats and politicians. She suggested that Charles Edward may have had some influence on instances of appeasement towards Germany in the 1930s such as British acceptance of the German remilitarisation of the Rhineland and the Munich Agreement.[1]

Second World War

Although Charles Edward was too old for active service during the Second World War, his three sons served in the Wehrmacht.[33] His son Hubertus was killed in action. His support for Nazism grew more intense during the war years and never relented.[4] Charles Edward probably ceased to act as an informal diplomat after 1940.[1] That year he helped mediate a diplomatic dispute between the British and German governments about the treatment of prisoners of war, stopping a number of prisoners on both sides from being shackled.[8]

He continued to wear uniforms and travel abroad to countries that were occupied by Germany, members of the Axis powers or neutral. Travelling abroad was a privilege afforded to few German civilians during the war years. It is unclear what Charles Edward was doing politically during this period, but he was being paid 4,000 Reichsmarks a month by the German government from a fund Hitler had organised for associates that were useful to him.[1] Hitler considered making him King of Norway after the war. In March 1945 the German government formed a "Committee for the Protection of European Humanity" of which Charles Edward was made chairman. This group was meant to negotiate with the Western Allies in order to gain better living conditions for the defeated Germans after the war. The committee members were in theory "uncompromised" Germans with fewer links to the regime. The quick collapse of Nazi Germany after that point meant that the time was not available for negotiations to happen.[8] In 1945, Hitler ordered that Charles Edward not be allowed to be captured because of the great deal of inside information that he possessed. According to Urbach, this meant that Hitler wanted him killed.[1]

In April 1945, Charles Edward agreed the surrender of Veste Coburg to US forces and gained their assistance in putting out a fire in the castle museum which had been started by the bombardment. Charles Edward was on the US army's list of suspected war criminals and was put under house arrest until being moved to a prisoner of war camp in November.[8] His interrogators saw him as ignorant, obnoxious and possibly mentally unstable. An interview in which he said he would accept an offer to participate in a new German government, made a series of demands relating to the idea and claimed that "no German is guilty of any war crimes" was deemed so useful for Allied propaganda that it was used for a radio broadcast in April 1945. He also made clear that he remained antisemitic and believed that Germans were naturally unsuited to democracy.[1]

Postwar period and death

After the end of World War II, Charles Edward was interned by the American military authorities from 1945 to 1946.[34] His sister lobbied unsuccessfully for his release on health grounds.[8] In 1950 (or August 1949, according to his Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry) Charles Edward was found by a denazification court to be a Mitläufer and Minderbelasteter (roughly: 'follower' and 'follower of lesser guilt').[7][4] Charles Edward also lost significant property as a result of his participation in World War II. Gotha was part of Thuringia, and therefore situated in the Soviet occupation zone. The Soviet Army confiscated much of the family's property in Gotha.[34] However, Coburg had become part of Bavaria in 1920[33] and was occupied by American forces. As such the family was able to retain extensive property in what would become West Germany.[34]

In April 1946, his daughter Sibylla gave birth to a son,[35] who became, upon birth, third in the line of succession to the Swedish throne. In January 1947, Sibylla's husband died in a plane crash,[36] and in October 1950, Gustaf V of Sweden died, at which point Charles Edward's grandson became the Crown Prince of Sweden, later becoming King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden.[37]

Charles Edward spent the last years of his life in seclusion, forced into relative poverty by the fines he had been required to pay by the denazification tribunal,[38] and the seizure of much of his property by the Soviets.[33][39] Though his lifestyle to a large extent returned to normal after his trial.[4] In 1953, Charles Edward was taken by ambulance to view the coronation of Elizabeth II as Queen of the United Kingdom in a cinema in Coburg. He reportedly appeared close to crying while watching his relatives, including his sister.[8] According to a column published that year in The Scotsman, Charles Edward had reestablished links with the Seaforth Highlanders, a British Army regiment of which he had once been colonel-in-chief which was stationed in Germany. It comments that:

On the occasion of a regimental ball, an invitation was sent to the Duke, with a note from the C.O. (Lieut.-Colonel P. J. Johnston) saying that, owing to the distance, it was doubtful if he would be able to attend, but it was the wish of all officers of the battalion that their old Colonel-in-Chief should be asked. The Duke replied that, although his health did not allow him to accept, he was deeply touched by the invitation, "renewing old connections which existed between the Seaforth Highlanders and myself for so many years, and which I honestly hope and wish will not be severed again". He said he would be pleased to receive as guest any comrade who should happen to pass Coburg, where he lives, and signed himself "Charles Edward. Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, Duke of Albany."[40]

Charles Edward died of cancer in his flat in Elsässer Straße, Coburg, on 6 March 1954, at the age of 69.[39] He had reportedly told his son, Friedrich Josias, that Queen Victoria had always wanted him to be a "good German".[4] His obituary in The Times commented that "... he was Hitler's man... Whether, and to what extent, he was admitted to the inner council of the Nazi gang is as yet an open question."[33] Representatives of various royal houses across Europe sent condolences but the British royal family did not comment. Charles Edward's death was officially mourned in Coburg. A civil servant who refused to fly a flag at half mast to commemorate his death was reported to the district council in Bayreuth and condemned by a member of the Parliament of Bavaria.[9] Charles Edward is buried at the Waldfriedhof Cemetery (Waldfriedhof Beiersdorf) near Schloss Callenberg, in Beiersdorf near Coburg.[4]

Legacy

In December 2007, Britain's Channel 4 aired an hour-length documentary about Charles Edward called Hitler's Favourite Royal. A review in The Guardian described the film as "A solid documentary on a feeble man and a wretched family."[41] Another review, in The Telegraph, suggested the documentary had been overly sympathetic to Charles Edward, stating that the "story emerged as a tale of pure tragedy. Which it undoubtedly was, in parts", but that he was depicted "As if the trauma of being elevated to a dukedom and losing it had somehow robbed him of his ability to tell right from wrong."[42]

Urbach wrote that there was some disagreement in the production team of the 2007 documentary about whether Charles Edward should be portrayed as a man who struggled with politics in a country that was foreign to him or as an ideological Nazi, and that this led to a contradictory depiction of his character. She said that the recovery of new evidence during the period between 2007 and 2015 showed that he was "obviously not a naive victim of circumstances but a very active supporter of Hitler".[1]

Urbach's 2015 book Go Betweens for Hitler discusses how various aristocrats including Charles Edward acted as informal diplomats for Nazi Germany. A review in The Times commented on Charles Edward that "For many years thereafter [the German Revolution], Carl Eduard was regarded as a mere footnote in history; a harmless, potty old aristocrat, washed up by the seismic upheavals of the early 20th century. However, that benign interpretation has been recently revised. We now know that Carl Eduard was a member of the Nazi Party, a sponsor of paramilitary terrorism and—as Urbach's excellent book demonstrates—an important 'go-between' for Hitler."[43]

Notes and references

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 Urbach, Karina (2017). Go-Betweens for Hitler (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 22–23, 28–33, 65–67, 146, 148–153, 158, 160, 171, 175–207, 214, 216, 309–310. ISBN 978-0191008672.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 "Biografie Karl Eduard (German)". Bayerische Nationalbibliothek. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ Reynolds, K.D. (28 September 2006). "Leopold, Prince, first duke of Albany". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/16475.

Leopold's wife was expecting a second child (Charles Edward, later duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, born on 19 July 1884) when he was sent to Cannes to escape the harsh weather early in 1884. While there, he slipped on a staircase, bringing on an epileptic fit and brain haemorrhage, from which he died at the Villa Nevada on 28 March 1884.

(Subscription or UK public library membership required.) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Zeepzat, Charlotte (3 January 2008). "Charles Edward, Prince, second duke of Albany". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/41068. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Burke, Bernard; Burke, John (1885). Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Peerage and Baronetage of the British Empire. Vol. 47. Burke's Peerage Limited. p. 103.

- ↑ "The Infant Duke Of Albany". Daily News (London). 5 December 1884. Retrieved 23 March 2023 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Oltmann, Joachim (18 January 2001). "Seine Königliche Hoheit der Obergruppenführer (German)". Zeit Online. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 Rushton, Alan R. (2018). Charles Edward of Saxe-Coburg: The German Red Cross and the Plan to Kill "Unfit" Citizens 1933-1945. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 3–6, 11--37, 62–65, 67–102, 105–109, 113–115, 142, 164–166, 172. ISBN 978-1-5275-1340-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Büschel, Hubertus (2016). Hitlers adliger Diplomat. Frankfurt: S. Fischer Verlag. pp. 47, 49–52, 55–60, 260–261. ISBN 9783100022615.

- 1 2 3 Urbach, Karina (2017). Go-Betweens for Hitler (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 28–33, 65–67, 175–197, 214, 216. ISBN 978-0191008672.

- ↑ "Unwilling Prince Is Now a German Duke". The New York Times. 20 July 1905. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- 1 2 "Kicked into the Kingdom". Wellsville Daily Reporter. 15 July 1905. p. 2.

- 1 2 Weir, Alison (18 April 2011). Britain's Royal Families: The Complete Genealogy. Random House. p. 314. ISBN 9781446449110. Retrieved 31 December 2017 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Foreign Intelligence—Germany—Marriage of the Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha". London and China Express. 13 October 1905. p. 7 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Sandner, Harald (2004). "II.8.0 Herzog Carl Eduard". Das Haus von Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha 1826 bis 2001 (in German). Andreas, Prinz von Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha (preface). 96450 Coburg: Neue Presse GmbH. p. 195. ISBN 3-00-008525-4.

Der deutsche Emperor Wilhelm II. kümmert sich persönlich um ihn, Carl Eduard ist wiederholt Gast am Emperorlichen Hof in Berlin und wird der 'siebte Sohn des Emperors' genannt.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ↑ Urbach, Karina (2017). Go-Betweens for Hitler (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 28, 30–33, 65–67, 175–197. ISBN 978-0191008672.

- ↑ "The Duke of Saxe-Coburg Inspects Veterans". Daily Mirror. 18 August 1910. p. 13 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ H.H. Prince Andreas of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (2015). I Did It My Way. Memoirs of HH Prince Andreas of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Eurohistory.com, pp. 51, 57.

- ↑ Weir, Alison (2008). Britain's Royal Families, The Complete Genealogy. London, UK: Vintage Books. pp. 314–15. ISBN 978-0-09-953973-5.

- ↑ Priesner, Rudolf (1977). Herzog Carl Eduard zwischen Deutschland und England: eine tragische Auseinandersetzung (in German). Hohenloher Druck- und Verlagshaus. pp. 90–94. ISBN 3873540630.

- ↑ "Royal Children of Europe: Saxe-Coburg-Gotha". The Sphere. 11 July 1914. p. 24 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Swift MacNeill, J. G. (11 April 1916). "A Slur on the House of Lords (letter to the editor)". The Times.

- ↑ Palmer, Charles (5 August 1916). "Traitors Near the Throne". John Bull. British Newspaper Archive. p. 8.

- ↑ "Traitor Peers". Taunton Courier and Western Advertiser. 2 April 1919. p. 1 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "The Scandal of our Traitor Dukes". Sunday Post. 30 March 1919. p. 22 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "Foreign Legislation—Great Britain". American Bar Association Journal. Vol. 5. Chicago: American Bar Association. 1919. p. 289.

- 1 2 3 4 Petropoulos, Jonathan (1 February 2018). "Hubertus Büschel. Hitlers adliger Diplomat: Der Herzog von Coburg und das Dritte Reich". The American Historical Review. 123 (1): 320–321. doi:10.1093/ahr/123.1.320. ISSN 0002-8762 – via Book Review Digest Plus (H.W. Wilson).

- ↑ "Biografie Karl Eduard (German)". Bayerische Nationalbibliothek. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ "Biografie Karl Eduard (German)". Bayerische Nationalbibliothek. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ See Henderson, Failure of a Mission: Berlin 1937–1939, London 1940, p. 19.

- ↑ Cadbury, Deborah (10 March 2015). Princes at War: The Bitter Battle Inside Britain's Royal Family in the Darkest Days of WWII. PublicAffairs. p. 53. ISBN 9781610394048. Retrieved 31 December 2017 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Moorhouse, Roger (18 July 2015). "Go Betweens for Hitler by Karina Urbach". The Times. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Duke of Saxe-Coburg". The Times. 8 March 1954. p. 10.

- 1 2 3 Biographie, Deutsche. "Karl Eduard - Deutsche Biographie". www.deutsche-biographie.de (in German). Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ↑ Rudberg, Erik, ed. (1947). Svenska dagbladets årsbok 1946 (in Swedish). Stockholm: Svenska Dagbladet. p. 43. SELIBR 283647.

- ↑ "Prince and opera star killed in plane crash". Ottawa Citizen. Associated Press. 24 January 1947. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ "Kungens liv i 60 år" [King's life for 60 years] (in Swedish). Royal Court of Sweden. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ↑ Feuchtwanger, E. J. (31 December 2017). Albert and Victoria: The Rise and Fall of the House of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. A&C Black. p. 278. ISBN 9781852854614. Retrieved 31 December 2017 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 Cadbury, Deborah (10 March 2015). Princes at War: The Bitter Battle Inside Britain's Royal Family in the Darkest Days of WWII. PublicAffairs. p. 306. ISBN 9781610394048. Retrieved 31 December 2017 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Duke of Albany". The Scotsman. 27 January 1953. p. 6 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Mangan, Lucy (7 December 2007). "Last night's TV". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ↑ O'Donovan, Gerald (7 December 2007). "Last night on television: Hitler's Favourite Royal (Channel 4) - Spoil (Channel 4)". www.telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ↑ Moorhouse, Roger (18 July 2015). "Go Betweens for Hitler by Karina Urbach". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

Notes

- ↑ He used the German language version of his name in Germany,[1] this article uses the English language version of his name throughout.

- ↑ Now located in Wiltshire.

- ↑ German equivalent to a grammar school

- ↑ Charles Edward had been at Eton with Henderson and this photograph may have been taken at a meeting of the Anglo-German Fellowship that Henderson addressed in May 1937, shortly after his appointment as British ambassador.[30]

Further reading

- Sandner, Harald (2010). Hitlers Herzog: Carl Eduard von Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha: die Biographie. Aachen.

External links

![]() Media related to Charles Edward, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Charles Edward, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha at Wikimedia Commons