Chinese poetry is poetry written, spoken, or chanted in the Chinese language, and a part of the Chinese literature. While this last term comprises Classical Chinese, Standard Chinese, Mandarin Chinese, Yue Chinese, and other historical and vernacular forms of the language, its poetry generally falls into one of two primary types, Classical Chinese poetry and Modern Chinese poetry.[1][2]

Poetry is consistently held in high regard in China, often incorporating expressive folk influences filtered through the minds of Chinese literati.[3] Poetry provides a format and a forum for both public and private expressions of deep emotion, offering an audience of peers, readers, and scholars insight into the inner life of Chinese writers across more than two millennia.[4] Chinese poetry often reflects the influence of China's various religious traditions.[5]

Classical Chinese poetry includes, perhaps first and foremost shi (詩/诗), and also other major types such as ci (詞/词) and qu (曲). There is also a traditional Chinese literary form called fu (賦/赋), which defies categorization into English more than the other terms, but perhaps can best be described as a kind of prose-poem.[2] During the modern period, there also has developed free verse in Western style. Traditional forms of Chinese poetry are rhymed, however the mere rhyming of text may not qualify literature as being poetry; and, as well, the lack of rhyme would not necessarily disqualify a modern work from being considered poetry, in the sense of modern Chinese poetry.[1]

Beginnings of the tradition: Shijing and Chuci

The earliest extant anthologies are the Shi Jing (詩經) and Chu Ci (楚辭).[2] Both of these have had a great impact on the subsequent poetic tradition. Earlier examples of ancient Chinese poetry may have been lost because of the vicissitudes of history, such as the burning of books and burying of scholars (焚書坑儒) by Qin Shi Huang, although one of the targets of this last event was the Shi Jing, which has nevertheless survived.

Shijing

The elder of these two works, the Shijing (also familiarly known, in English, as the Classic of Poetry and as the Book of Songs or transliterated as the Sheh Ching) is a preserved collection of Classical Chinese poetry from over two millennia ago. Its content is divided into 3 parts: Feng (風, folk songs from 15 small countries, 160 songs in total), Ya (雅, Imperial court songs, subdivided into daya and xiaoya, 105 songs in total) and Song (頌, singing in ancestral worship, 40 songs in total).This anthology received its final compilation sometime in the 7th century BCE.[6] The collection contains both aristocratic poems regarding life at the royal court ("Odes") and also more rustic poetry and images of natural settings, derived at least to some extent from folksongs ("Songs"). The Shijing poems are predominantly composed of four-character lines (四言), rather than the five and seven character lines typical of later Classical Chinese poetry. The main techniques of expression (rhetorics) are Fu (賦, Direct elaborate narrative), bi (比, metaphor) and Xing (興, describe other thing to foreshadowing the main content).

Chuci

In contrast to the classic Shijing, the Chu Ci anthology (also familiarly known, in English, as the Songs of Chu or the Songs of the South or transliterated as the Chu Tz'u) consists of verses more emphasizing lyric and romantic features, as well as irregular line-lengths and other influences from the poetry typical of the state of Chu. The Chuci collection consists primarily of poems ascribed to Qu Yuan (屈原) (329–299 BCE) and his follower Song Yu, although in its present form the anthology dates to Wang I's 158 CE compilation and notes, which are the only historically reliable sources of both the text and information regarding its composition.[7] During the Han dynasty (206 BCE−220 CE), the Chu Ci style of poetry contributed to the evolution of the fu ("descriptive poem") style, typified by a mixture of verse and prose passages (often used as a virtuoso display the poet's skills and knowledge rather than to convey intimate emotional experiences). The fu form remained popular during the subsequent Six Dynasties period, although it became shorter and more personal. The fu form of poetry remains as one of the generic pillars of Chinese poetry; although, in the Tang dynasty, five-character and seven-character shi poetry begins to dominate.

Han poetry

Also during the Han dynasty, a folk-song style of poetry became popular, known as yuefu (樂府/乐府) "Music Bureau" poems, so named because of the government's role in collecting such poems, although in time some poets began composing original works in yuefu style. Many yuefu poems are composed of five-character (五言) or seven-character (七言) lines, in contrast to the four-character lines of earlier times. A characteristic form of Han Dynasty literature is the fu. The poetic period of the end of the Han Dynasty and the beginning of the Six Dynasties era is known as Jian'an poetry. An important collection of Han poetry is the Nineteen Old Poems.

Jian'an poetry

Between and over-lapping the poetry of the latter days of the Han and the beginning period of the Six Dynasties was Jian'an poetry. Examples of surviving poetry from this period include the works of the "Three Caos": Cao Cao, Cao Pi, and Cao Zhi.

Six Dynasties poetry

The Six Dynasties era (220−589 CE) was one of various developments in poetry, both continuing and building on the traditions developed and handed down from previous eras and also leading up to further developments of poetry in the future. Major examples of poetry surviving from this dynamic era include the works of the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove, the poems of the Orchid Pavilion Gathering, the Midnight Songs poetry of the four seasons, the great "fields and garden" poet "Tao Yuanming", the Yongming epoch poets, and the poems collected in the anthology New Songs from the Jade Terrace, compiled by Xu Ling (507–83). The general and poet Lu Ji used Neo-Taoist cosmology to take literary theory in a new direction with his Wen fu, or "Essay on Literature" in the Fu poetic form.

Tang poetry

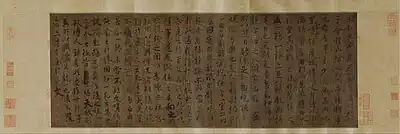

A high point of classical Chinese poetry occurred during the Tang period (618–907): not only was this period prolific in poets; but, also in poems (perhaps around 50,000 poems survive, many of them collected in the Complete Tang Poems). During the time of, poetry was integrated into almost every aspect of the professional and social life of the literate class, including becoming part of the Imperial examinations taken by anyone wanting a government post. By this point, poetry was being composed according to regulated tone patterns. Regulated and unregulated poetry were distinguished as "ancient-style" gushi poetry and regulated, "recent-style" jintishi poetry. Jintishi (meaning "new style poetry"), or regulated verse, is a stricter form developed in the early Tang Dynasty with rules governing the structure of a poem, in terms of line-length, number of lines, tonal patterns within the lines, the use of rhyme, and a certain level of mandatory parallelism. Good examples of the gushi and jintishi forms can be found in, respectively, the works of the poets Li Bai and Du Fu. Tang poetic forms include: lushi, a type of regulated verse with an eight-line form having five, six, or seven characters per line; ci (verse following set rhythmic patterns); and jueju (truncated verse), a four-line poem with five, six, or seven characters per line. Good examples of the jueju verse form can be found in the poems of Li Bai[8] and Wang Wei. Over time, some Tang poetry became more realistic, more narrative and more critical of social norms; for example, these traits can be seen in the works of Bai Juyi. The poetry of the Tang Dynasty remains influential today. Other Late Tang poetry developed a more allusive and surreal character, as can be seen, for example, in the works of Li He and Li Shangyin.

Song poetry

By the Song dynasty (960–1279), another form had proven it could provide the flexibility that new poets needed: the ci (词/詞) lyric—new lyrics written according to the set rhythms of existing tunes. Each of the tunes had music that has often been lost, but having its own meter. Thus, each ci poem is labeled "To the tune of [Tune Name]" (调寄[词牌]/調寄[詞牌]) and fits the meter and rhyme of the tune (much in the same way that Christian hymn writers set new lyrics to pre-existing tunes). The titles of ci poems are not necessarily related to their subject matter, and many poems may share a title. In terms of their content, ci poetry most often expressed feelings of desire, often in an adopted persona. However, great exponents of the form, such as the Southern Tang poet Li Houzhu and the Song dynasty poet Su Shi, used the ci form to address a wide range of topics.

Yuan poetry

Major developments of poetry during the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) included the development of types of poetry written to fixed-tone patterns, such as for the Yuan opera librettos. After the Song Dynasty, the set rhythms of the ci came to be reflected in the set-rhythm pieces of Chinese Sanqu poetry (散曲), a freer form based on new popular songs and dramatic arias, that developed and lasted into the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). Examples can be seen in the work of playwrights Ma Zhiyuan 馬致遠 (c. 1270–1330) and Guan Hanqing 關漢卿 (c. 1300).

Ming poetry

The Ming dynasty (1368–1644) poets include Gao Qi (1336–1374), Li Dongyang (1447–1516), and Yuan Hongdao (1568–1610).

Ming-Qing Transition

Ming-Qing Transition includes the interluding/overlapping periods of the brief so-called Shun dynasty (also known as Dashun, 1644–1645) and the Southern Ming dynasty (1644 to 1662). One example of poets who wrote during the difficult times of the late Ming, when the already troubled nation was ruled by Chongzhen Emperor (reigned 1627 to 1644), the short-lived Dashun regime of peasant-rebel Li Zicheng, and then the Manchu Qing dynasty are the so-called Three Masters of Jiangdong: Wu Weiye (1609–1671), Qian Qianyi (1582–1664), and Gong Dingzi (1615–1673).

Qing poetry

The Qing dynasty (1644 to 1912) is notable in terms of development of the criticism of poetry and the development of important poetry collections, such as the Qing era collections of Tang dynasty poetry known as the Complete Tang Poems and the Three Hundred Tang Poems. Both shi and ci continued to be composed beyond the end of the imperial period.

Post-imperial Classical Chinese poetry

Both shi and ci continued to be composed past the end of the imperial period; one example being Mao Zedong, former Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party, who wrote Classical Chinese poetry in his own calligraphic style.

Modern (post-classical) poetry

Modern Chinese poetry (新诗/新詞 "new poetry") refers to the modern vernacular style of poetry, as opposed to the traditional poetry written in Classical Chinese language. Usually Modern Chinese poetry does not follow prescribed patterns.[1] Poetry was revolutionized after 1919's May Fourth Movement, when writers (like Hu Shih) tried to use vernacular styles related with folksongs and popular poems such as ci closer to what was being spoken (baihua) rather than previously prescribed forms.[1][3] Early 20th-century poets like Xu Zhimo, Guo Moruo (later moved to the proletarian literature) and Wen Yiduo sought to break Chinese poetry from past conventions by adopting Western models.[1] For example, Xu consciously follows the style of the Romantic poets with end-rhymes.

In the post-revolutionary Communist era, poets like Ai Qing used more liberal running lines and direct diction, which were vastly popular and widely imitated.

At the same time, in Taiwan has flourished modernist poetry, including avant-garde and surrealism, led by Qin Zihao (1902–1963) and Ji Xian (b. 1903). Most influential poetic groups were founded in 1954 the "Modernist School", the "Blue Star", and the "Epoch".[1][9]

In the contemporary poetic scene, the most important and influential poets are in the group known as Misty Poets, who use oblique allusions and hermetic references. The most important Misty Poets include Bei Dao, Duo Duo, Shu Ting, Yang Lian, and Gu Cheng, most of whom were exiled after the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. A special case is the mystic poet Hai Zi, who became very famous after his suicide.[1][10][11]

However, even today, the concept of modern poetry is still debated. There are arguments and contradiction as to whether modern poetry counts as poetry. Due to the special structure of Chinese writing and Chinese grammar, modern poetry, or free verse poetry, may seem like a simple short vernacular essay since they lack some of the structure traditionally used to define poetry.[1]

See also

General

- Classical Chinese poetry

- Chinese art

- Shi (poetry) (the Chinese term for poetry)

- Chinese literature

- Chinese classic texts

- List of national poetries

- Modern Chinese poetry

Poetry works and collections

Individual poets

Lists of poets

Important English translators

English-language translation collections

Technical factors of poetry

Notes and references

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Greene 2012a.

- 1 2 3 Greene 2012b.

- 1 2 Greene 2012c.

- ↑ Cai 2008, pp. xxi, 1.

- ↑ Williams 2022.

- ↑ Yip 1997, p. 31.

- ↑ Yip 1997, p. 54.

- ↑ 五言絕右丞,供奉(白曾供奉翰林,故云),七言絕龍標,供奉,絕妙古今 ,別有天地。

- ↑ Lupke 2017.

- ↑ Klein 2017.

- ↑ "A Brief Guide to Misty Poets". Poets.org. Archived from the original on 2010-04-12. Retrieved 2010-10-19.

Bibliography

Souces

- Cai, Zong-qi, ed. (2008). How to Read Chinese Poetry: A Guided Anthology. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-13941-1.

- Cui, Jie; Cai, Zong-qi, eds. (2012). How to Read Chinese Poetry Workbook. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-15658-8.

- Davis, A. R., ed. (1970). The Penguin Book of Chinese Verse. Baltimore: Penguin Books.

- Greene, Roland; et al., eds. (2012a). "Modern poetry of China". The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics (4th rev. ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 232–235. ISBN 978-0-691-15491-6.

- Greene, Roland; et al., eds. (2012b). "Poetry of China". The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics (4th rev. ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15491-6.

- Greene, Roland; et al., eds. (2012c). "Popular poetry of China". The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics (4th rev. ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15491-6.

- Holland, Gill (1986). Keep an Eye on South Mountain: Translations of Chinese Poetry.

- Klein, Lukas (2017). "Poems from Underground". In Wang, David Der-wei (ed.). A New Literary History of Modern China. Harvard, Ma: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. pp. 718–724. ISBN 978-0-674-97887-4.

- Liu, James J.Y. (1966). The Art of Chinese Poetry. ISBN 0-226-48687-7

- Liu, Wu-Chi; Irving Yucheng Lo eds. (1990) Sunflower Splendor: Three Thousand Years of Chinese Poetry. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-20607-3

- Lupke, Christopher (2017). "Modernism versus Nativism in 1960s Taiwan". In Wang, David Der-wei (ed.). A New Literary History of Modern China. Harvard, Ma: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. pp. 669–673. ISBN 978-0-674-97887-4.

- Owen, Stephen (1996). An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911.

- Williams, Nicholas Morrow (2022). Chinese Poetry as Soul Summoning: Shamanistic Religious Influences on Chinese Literary Tradition. Cambria Press. ISBN 9781621966234.

- Yip, Wai-lim (1997). Chinese Poetry: An Anthology of Major Modes and Genres. Durham; London: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-1946-2.

Further reading

- Haft, Lloyd, ed. (1989). A Selective Guide to Chinese Literature, 1900–1949. Vol. 3: The Poem. Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-08960-8.

External links

- The Red Brush – Writing Women of Imperial China

- The Columbia University Press web page accompanying Cai 2008 has PDF and MP3 files for more than 75 poems and CUP's web page accompanying Cui 2012 includes MP3 files of modern Chinese translations for dozens of these.

- Olga Lomová, Traditional Chinese Poetry (Oxford Bibliographies Online: Chinese Studies). Available through libraries by subscription. Selective, annotated bibliography.