| Christina of Denmark | |

|---|---|

Christina of Denmark, Duchess of Milan and of Lorraine 1558, by François Clouet | |

| Duchess consort of Milan | |

| Tenure | 4 May 1534 – 24 October 1535 |

| Duchess consort of Upper Lorraine | |

| Tenure | 14 June 1544 – 12 June 1545 |

| Born | November 1521 Nyborg, Denmark |

| Died | 10 December 1590 (aged 69) Tortona, Alessandria, Duchy of Milan |

| Burial | Cordeliers Convent, Nancy, Duchy of Lorraine |

| Spouse | |

| Issue | |

| House | Oldenburg |

| Father | Christian II of Denmark |

| Mother | Isabella of Austria |

| Danish Royalty |

| House of Oldenburg Main Line |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

| Christian II |

|

Christina of Denmark (Danish: Christine af Danmark; November 1521 – 10 December 1590) was a Danish princess, the younger surviving daughter of King Christian II of Denmark and Norway and Isabella of Austria. By her two marriages, she became Duchess of Milan, then Duchess of Lorraine. She served as the regent of Lorraine from 1545 to 1552 during the minority of her son. She was also a claimant to the thrones of Denmark, Norway and Sweden in 1561–1590 and was sovereign Lady of Tortona in 1578–1584.

Early life

Christina was born in Nyborg in central Denmark in 1521 to King Christian II of Denmark, Sweden, and Norway and his wife Isabella of Austria, the third child of Duke Philip of Burgundy and Queen Joanna of Castile. In January 1523, nobles rebelled against her father and offered the throne to his uncle, Duke Frederick of Holstein. Christina and her sister and brother followed their parents into exile in April of the same year, to Veere in Zeeland, the Netherlands, and were raised by the Dutch regents, their grandaunt and aunt, Margaret of Austria and Mary of Hungary. Her mother died on 19 January 1526. In 1532, her father Christian II of Denmark was imprisoned in Denmark after an attempt to retake his throne. The same year, her brother died, and she became second in line to her father's claim to the Danish throne after her elder sister Dorothea.

Christina was given a good education by her aunt, the regent of the Netherlands, under supervision of her governess, Madame de Fiennes. She was described as a great beauty, intelligent and lively, and enjoyed hunting and riding. As a ward of her uncle the Emperor, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, and a member of the Imperial house, she was a valuable pawn on the political marriage market. In 1527, Thomas Wolsey, Primate of England, suggested that Henry FitzRoy, Duke of Richmond and Somerset, the illegitimate son of Henry VIII be married to Christina or Dorothea, but the Habsburgs did not wish for them to marry someone born out of wedlock. In 1532, Francesco II Sforza, Duke of Milan, after being denied a match with Dorothea, proposed to marry the 11 year old Christina. Charles consented not only to a proxy marriage but to an immediate consummation once Christina arrived in Milan.[1] Her aunt, believing the princess too young to consummate a marriage, delayed Christina's departure until 11 March 1533 by informing the Milanese envoy that she was ill and taking her to another part of the Netherlands for "serious affairs".[2][3]

Duchess of Milan

On 23 September 1533 in Brussels, Christina was married by proxy to Francesco II Sforza, Duke of Milan, through his representative Count Massimiliano Stampa. On 3 May 1534, Christina made her official entry in Milan among great festivities, and on 4 May, the second wedding ceremony was celebrated in the hall of the Rocchetta.[4] Christina's relationship with Francesco was reportedly good, and she was very popular in Milan, where she was regarded as a symbol of peace and hope for the future after decades of war, and her beauty was much admired. She enjoyed hunting parties, and the palace was redecorated and beautified for her. When she was given her own court, her chief lady in waiting was Francesca Paleologa of Montferrat, spouse of Constantine Arianiti Comnenus, titular Prince of Macedonia, who was to become one of her most intimate lifelong friends.[4]

Francesco II Sforza was at that time very weak, as his health had never recovered after he survived a poison attempt years before, and there was concern that he would never be able to have children, and die without heirs. According to the marriage settlement, the Duchy of Milan was to become a part of the Empire if it did not result in issue. She and Francesco had no children.

Francesco II Sforza died in October 1535, leaving her widowed when she was thirteen. Her rights as a widow to the town of Tortona for life was secured, while the Duchy was incorporated with the Empire. However, Massimiliano Stampa remained in charge as castellan of Milan, and Christina remained in the ducal residence. Charles V supported her wish to stay in Milan, as she was very popular there and her presence was regarded as a protection to Milanese independence and calm.[4] As a way to save Milanese independence, Stampa suggested that she marry the heir to the throne of Savoy, prince Louis of Piedmonte, but the plan failed because of his death shortly thereafter. Pope Paul III suggested that she marry the son of his niece Cecilia Farnese, who, though a few years older than she, was raised as her foster son in the court of Milan after the death of his mother. When the French king repeated his claims to the throne of Milan on behalf of his son, the duke of Orléans, a marriage was suggested to the youngest son of the French monarch, the duke of Angoulême, but Charles V refused the match unless Angoulême, instead of Orléans, was granted the Duchy of Milan, should he recognize the French claims on the Duchy.[4] Christina welcomed duchess Beatrice of Savoy[5] when Savoy was occupied by the French, and was present on the meeting between Beatrice and the Emperor in Pavia in May 1536. In December of that year, Milan was officially given over to the command of an Imperial official, and Christina was escorted to Pavia. Before she left, she took the title Lady of Tortona, and had a governor named to manage her dower city for her.[4]

In October 1537, Christina went to live at the court of her aunt, the Governor of the Low Countries, Dowager Queen Mary of Hungary, by way of Innsbruck, visiting her sister at the Palatinate before arriving in Brussels in December. Christina was a favorite of Mary.

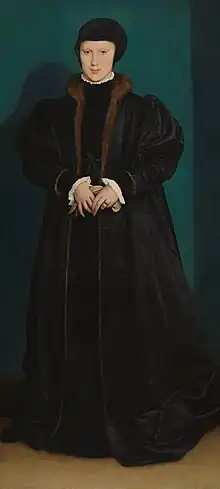

First widowhood

After Jane Seymour, the third wife of Henry VIII, died in 1537, Christina was considered as a possible bride for the English king. The German painter Hans Holbein was commissioned to paint portraits of noblewomen eligible to become the English queen. On 10 March 1538, Holbein arrived in Brussels with the diplomat Philip Hoby to meet Christina. Hoby arranged with Benedict, the Master of Christina's household, for a sitting the next day. Christina sat for the portrait for three hours wearing mourning dress. Her rooms in Brussels were hung with black velvet, black damask and a black cloth-of-estate.[6] Christina, then only sixteen years old, made no secret of her opposition to marrying the English king, who by this time had a reputation around Europe for his mistreatment of wives: Henry had annulled his marriage to his first wife Catherine of Aragon (Christina's great-aunt), and beheaded his second, Anne Boleyn. She supposedly said, "If I had two heads, one should be at the King of England's disposal."[7] It was also obvious that Mary of Hungary was less than enthusiastic about the match, being no admirer of Henry VIII. Mary, and Christina's mother, were Henry's first wife's nieces. Henry pursued the marriage until January 1539, when the attitude of Mary made it obvious that the match would never take place. Thomas Wriothesley, the English diplomat in Brussels, advised Thomas Cromwell that Henry should; "fyxe his most noble stomacke in some such other place."[8]

William, Duke of Cleves, proposed to Christina. William had been made duke of Guelders by will of the last childless duke of Guelders. This was contested by the Emperor, who wished to incorporate Guelders with the Netherlands. It was also contested by the Duchy of Lorraine, who regarded Guelders as their property through Philippa of Guelders, and the purpose of his proposal was to secure the Emperors support of his succession to Guelders against the claims of Lorraine.[4] The other suitors were Francis, heir to the Duchy of Lorraine, and Antoine, Duke of Vendôme, later Antoine of Navarre. The proposal of William of Cleves was refused by Charles V because of the Guelders question.[4]

Christina herself was, in fact, in love with René of Chalon, Prince of Orange, in 1539–40. It was noted in court that René was in love with Christina and courted her, and that she returned his feelings.[4] An eventual love match was supported by Christina's sister Dorothea and by her brother-in-law Frederick, who stated that he would like his sister-in-law to marry for love if she could.[4] The regent Mary condoned the courtship unofficially, but she gave no official comment because she wished for her brother the emperor to state whether he needed Christina for a political marriage before she allowed her to enter a love match. In October 1540, Charles V forced René of Orange to marry Anne of Lorraine, and then declared Christina engaged to Anne's brother, Francis of Lorraine, to strengthen the alliance between the Empire and Lorraine after it had been damaged in the Guelders affair.

In February 1540, Christina aided her sister Dorothea, who was sent to the Emperor on the commission of her spouse Frederick, to plead her father's cause with the Emperor, and prevent a renewal of the truce between the Netherlands and King Christian III of Denmark. After consulting Archbishop Carondelet, the president of the council, and Nicolas Perrenot de Granvelle, Dorothea and Christina sent the following official petition to the Emperor: "My sister and I, your humble and loving children, entreat you, as the fountain of all justice, to have compassion on us. Open the prison doors, which you alone are able to do, release my father, and give me advice as to how I may best obtain the kingdom which belongs to me by the laws of God and man."[4] Their appeal was, however, unsuccessful.

Duchess of Lorraine

On 10 July 1541, Christina married Francis, Duke of Bar, in Brussels. Francis had been betrothed to Anne of Cleves, who became the fourth wife of Henry VIII. In August, Christina and Francis reached Pont-à-Mousson, in Lorraine, where they visited the dowager duchess Philippa, and continued to the capital in Nancy escorted by the Guise family. In November 1541, Christina, her spouse, and father-in-law visited the French court in Fontainebleau, where they were forced to cede the fort of Stenay to France. Christina prevented this from creating a rift between Lorraine and the Emperor. During the war between France and the Emperor in 1542, she lived in the French court at several occasions visiting her aunt, Queen Eleanor. Christina gave birth to her son Charles III 18 February 1543. In February 1544, Christina and her sister Dorothea visited the Emperor at Speyer, reportedly to implore him to make peace with France, though without success. Her daughter Renata was born 20 April 1544.

On 19 June 1544, Francis succeeded his father as Duke of Lorraine. In July, he and Christina hosted the Emperor in Lorraine, but failed to convince him to start peace negotiations. In August, the Emperor ordered that the residence of the Guise family in Joinville be spared by the Imperial army on Christina's request, as she had asked him for this favor out of consideration of Anne of Lorraine. The same month, Charles V asked Christina to prevent Francis from visiting the French court, as he would take this as a sign of peace negotiations, but she replied that he had already left. When the war was finally ended later the same year, Christina was present at the peace celebrations in Brussels. Christina acted as the political adviser of Francis.[9] This was noted during the Diet of Speyer (1544). Their relationship was described as happy: they shared a common interest in music and architecture, and planned to redecorate the palace in Nancy. At one occasion during the marriage, Christina referred to herself as the happiest woman in the world.

Regent of Lorraine

Francis died on 12 June 1545, leaving Christina as Regent of Lorraine and the guardian of her minor son. His will was contested by a party headed by Count Jean I de Salm (d. 1560), who regarded Christina as a puppet of the emperor, and so wished to place her brother-in-law as her co-regent. Christina, having recently given birth to her third child, Dorothea 24 May 1545, postponed the funeral, withdrew to her dower estate, and sent word to Charles V. On 6 August, after mediation from the emperor, Christina and her brother-in-law were declared co-regents during the minority, with both of their seals necessary to issue orders, but with Christina as the main regent with sole custody of the minor monarch. In October 1546, she hosted the French king at Bar, who tried to convince her to marry the Count of Aumale. However, she refused to marry again. Christina was present at the Diet of Augsburg in 1547 with her aunt Mary of Hungary and dowager princess Anne of Orange. A marriage was discussed between Christina and king Sigismund of Poland during the diet. She was also courted by Albert Alcibiades, Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach and Burgrave of Nuremberg, whose infatuation with her attracted attention. She opposed the marriage of her brother-in-law Nicolas of Vaudemont and Margaret of Egmont, because she feared it would displease France. In March 1549, she made an official visit to Brussels to be present at the welcome of Prince Philip of Spain to the Netherlands. On this occasion, Philip gave her so much attention that it caused discontent, and she left for Lorraine to avoid any complications. In Lorraine, Christina was careful to maintain good relations to the Guise family, who were closely affiliated with the French court, and she had Stenay, Nancy and several other strongholds fortified against an expected French attack. In September 1550, she had Charles the Bold reburied in Lorraine. The same year, she attended the Diet of Augsburg for the second time, and was much celebrated as a hostess for the attending princes. In May 1551, she hosted her sister and brother-in-law in Lorraine.

In September 1551, France prepared for war against the Empire. Being counted as an Imperial ally, Lorraine was in immediate danger. Christina tried to ally herself with the Guise family, sent warnings to the Emperor, and asked both him and Mary of Hungary for assistance in defending Lorraine, as she had noted French war preparations along the border. She warned that Lorraine had no army of its own, and that there was opposition to the Emperor among the local nobility, which would welcome a French invasion. On 5 February 1552, Henry II of France marched toward the German border, reaching Joinville on the 22nd. Christina failed to secure help from the Netherlands and the Emperor, and on 1 April, she traveled to the duchess Antoinette of Guise in Joinville, in the company of princess dowager Anne of Lorraine, to ask the French monarch to respect the neutrality of Lorraine. Her appeal was successful, and the king assured her that Lorraine was in no danger of being attacked.

On 13 April 1552, France invaded the Duchy of Lorraine, and the French king entered the capital of Nancy. The day after, Christina was informed that she was deprived of the custody of her son, whom the king was to take with him when he left and who was thereafter to be brought up at the French court, and that she and all other Imperial officials in Lorraine were deprived of any offices in the rule of Lorraine. All Imperial officials were to leave the duchy: Christina herself was not asked to leave, but she was deprived of any share in the regency, and Lorraine was to be ruled solely by her former co-regent, the duke of Vaudemont, who would be asked to make an oath of loyalty to France. On a famous occasion, Christina entered the hall Galerie des Cerfs, where the king and his court were gathered. Dressed in her widow's black and a white veil, begged him to take all he wished save her son. This scene was described as touching by the courtiers present, but the king merely replied that Lorraine was too close to the enemy border for him to leave her son, and escorted her out.

Christina retired to her dower house in Denœuvre. In May 1552, her brother-in-law Vaudemont informed her of his wish to open the gates for the Imperial army, and letters from her were intercepted, after which Henry II of France ordered her to leave Lorraine. Because of the warlike state of the area, she could not reach the Netherlands, but took refuge in Schlettstadt, until she could reunite with her uncle the emperor when he reached the area with his army in September. She was then able to depart for the court of her sister in Heidelberg, in the Palatinate, with her daughters and former sister-in-law Anne, and from there, finally, to the court of her aunt Mary in Brussels in the Netherlands, where she settled.

Exile

Christina received marriage proposals from King Henry of Navarre, Adolf of Holstein, the prince of Piedmont, and Albert of Brandenburg. The latter promised to recover the kingdom of her father for her. However, she refused to marry, and focused on negotiations with France to recover the custody of her son. She was present at the abdication of Emperor Charles V in Brussels in October 1555, followed by the ceremony when her aunt Mary of Hungary stepped down from the regency of the Netherlands. She took leave of them on their departure to Spain in October 1556. The emperor suggested that Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy should marry her, and in parallel be made governor of the Netherlands, but though he replaced Mary as governor that year, the match never took place.

After the war between France and the Empire ended, she applied to the French for permission to return to Lorraine and reunite with her son there. This was not possible. The French monarch pointed out in 1556 that her son would be declared of legal majority, and her claim to regency moot in any case in another year. Furthermore, King Philip did not wish to give her permission to leave Brussels, because he enjoyed her company, and her popularity in the Netherlands was of use to him.

She visited England for the first time in April 1555, though not much information are recorded of this first visit. In February–May 1557, she and Margaret of Parma visited the court of Mary I of England. They were welcomed by Queen Mary with a grand banquet at Whitehall. The rumoured reason for their visit was that they planned to take the Princess Elizabeth with them to give her in marriage to the Duke of Savoy. This marriage plan was blocked by the Queen. Christina made a good impression in London during her visit, and reportedly made friends with the Lords Arundel and Pembroke, visited several Catholic shrines, and was shown the Tower of London. There was, however, some displeasure from the side of Queen Mary, because of the affection and attention she was given by Philip. She was also denied a visit to see Princess Elizabeth, who was kept in seclusion at Hatfield at the time. In May, she returned to the Netherlands.

Christina was finally, through the negotiation of her former brother-in-law Nicolas de Vaudemont, given permission to meet her son. The meeting took place in the border village Marcoing in May 1558. She was invited to his wedding in Paris in 1559, but declined as she was by then in mourning for her foster-mother, Mary of Hungary, and because she had by then accepted the task of presiding at the peace conference between France and Spain.

In October–September 1558, Christina presided as a mediator in the peace negotiations at Cercamp, upon request. The negotiations were discontinued because of the death of Mary of Hungary. When the peace conference was opened again, she again resumed her post as the president of the conference, which took place in Le Cateau-Cambrésis, in February–April 1559. The peace treaty was regarded as a triumph of Christina's diplomacy skills.

When the Duke of Savoy resigned from his post as governor of the Netherlands in May 1559, Christina was a popular choice to be his successor. She was popular in all classes in the Netherlands, where she had been raised and by whom she was regarded as Dutch. She had strong connections among the Dutch nobility, and her success during the peace conferences in Cercamp and Câteau-Cambrésis had given her a good reputation as a diplomat. She had already been suggested for the post as governor during the summer of 1558. However, her advantages did in fact not work in her favor in the eyes of King Philip of Spain, as he regarded her popularity with the Dutch and especially her friendship with Prince William of Orange with suspicion, and in June, Margaret of Parma was appointed instead. This caused a conflict between Christina and Margaret, and in October, Christina joined her son Charles and his wife in Lorraine.

Claimant

In Lorraine, Christina served as adviser to her son, especially in repairing the finances of Lorraine after the war and winning the loyalty of the local nobility, and assisted her daughter-in-law as hostess. In March 1560, she was again appointed regent of Lorraine during the absence of her son and daughter-in-law at the French court. She was present at the coronation of Charles IX in Reims in May 1561, and of Emperor Maximilian in Frankfurt in 1562. Her son Charles made his state entry to Nancy in May 1562 and officially took over the regency. However, he continued to rely on Christina as his adviser in affairs of state. In 1564, she concluded an agreement with the Bishop of Toul, by which he granted his temporalities to the Duke of Lorraine with the consent of the Pope. As the political adviser of her son, who often preferred to delegate political tasks to her, she had a strong position in the Ducal court in Lorraine, in particular as her daughter-in-law Claude preferred to spend her time at the French court, which she often visited. However, she was worried over the influence of the French queen dowager Catherine de' Medici, whom she suspected of trying to influence Lorraine, and in trying to disturb her relationship to her son, in an attempt to deprive her of her influence in the affairs of state.

At the death of her father, in prison in Denmark in 1559, her elder sister Dorothea assumed the claimant title of Queen of Denmark in exile as the heir of her father's claim.[4] She would however need the help of her mother's Habsburg dynasty to press her claims, but as a childless widow beyond the usual childbearing age, Dorothea was no longer considered politically useful, and the Habsburg dynasty showed no interest in helping her take the throne. The Danish loyalists loyal to her father's line, headed by the exiled Peder Oxe, therefore asked Christina to persuade Dorothea to surrender her claims to Christina and her son.[4] Christina made Oxe a part of the Ducal council, and in 1561, she visited Dorothea, and reportedly followed his advice and convinced Dorothea to surrender her claim.[4] After this, Christina styled herself the rightful Queen of Denmark, Norway and Sweden. In February 1563, she referred to herself as "Christina, by the grace of God Queen of Denmark, Sweden, and Norway, Sovereign of the Goths, Vandals, and Slavonians, Duchess of Schleswig, Dittmarsch, Lorraine, Bar, and Milan, Countess of Oldenburg and Blamont, and Lady of Tortona."[4] In reality, she had no access to these thrones and had difficulty pressing her claim to them.

In 1561, Christina planned to marry her daughter Renata to King Frederick II of Denmark.[4] However, on the outbreak of the Nordic Seven Years' War between Denmark-Norway and Sweden in 1563, these plans were interrupted. She was aided by Peder Oxe, the adventurer Wilhelm von Grumbach and his allies, who attempted to dethrone her second cousin king Frederick II of Denmark in her favour, and advised her to raise an army an invade Jutland, by which she would be welcomed by the Danish nobility, at that time in opposition to the Danish monarch. From 1565 to 1567, Christina negotiated with king Eric XIV of Sweden to create an alliance between Sweden and Denmark-Norway through a marriage between Renata and Eric XIV.[4] The plan was for Christina to conquer Denmark with the support of Sweden, a plan Eric agreed to, if she could secure the support from the Emperor and the Netherlands.[4] In 1566, Christina struck a medal referring to herself with the title Queen of Denmark, with the motto: Me sine cuncta ruunt (Without me all things perish).[4] However, Emperor Ferdinand was against the plan because the destructive effect it would have of the power balance in Germany, where Saxony, being strongly allied with Denmark, opposed Christina's claims. Nor did she manage to acquire the support of Philip of Spain.[4] The planned marriage alliance between Lorraine and Sweden was finally terminated when Eric XIV married his non-noble lover Karin Månsdotter in 1567.[4] In 1569, Christina still entertained hopes to press her claims to the Danish throne, but was met with the reply from Cardinal Granvelle, that the Netherlands would never turn against Denmark; that the Emperor would oppose it, and that Spain was occupied elsewhere. With the end of the Nordic Seven Years' War in 1570, Christina no longer worked actively in this matter.

In June 1568, Christina was among those who petitioned Philip of Spain for mercy on behalf of the Count of Egmont. The same year, her daughter Renata married Duke William of Bavaria. Reportedly, Christina spent some time in Bavaria, before returning to Lorraine in 1572. In 1574, she participated in the Mornay Plot to depose John III of Sweden and provided the conspirator Charles de Mornay with funds through her intermediary Monsieur La Garde.[10]

In August 1578, she left for Tortona in Italy, a fief given to her by her first husband, where she lived to her death, styled as "Madame of Tortona". She had sovereign powers in Tortona for life, and actively participated in the rule of the city. Her rule over Tortona has a good reputation in history: she is said to have reformed abuses, put an end to a feud with Ravenna, obtained the restitution of lost privileges, and protected the rights of Tortona against the hated Spaniard rule. She was popular in Tortona, often receiving supplicants, and socializing with the local Milanese nobility. In June 1584, she was informed by the Spanish Viceroy that her rights as sovereign of Tortona was henceforth extinct, but she was allowed to remain in residence and live on the income of Tortona for life. She also continued to plead for Tortonese rights from the Spanish viceroy.

Her son was Charles III, Duke of Lorraine, namesake of her uncle, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. The current Belgian and Spanish royal families and the ruling family of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg descends from him, as do the former reigning families of Austria, Bavaria, Brazil, France, Naples, Parma, Portugal, Sardinia (Italy), and Saxony. Her daughter, Renata of Lorraine, married William V, Duke of Bavaria, and it is through her that the current Danish, Norwegian and Swedish royal families, and the former Greek royal, and Russian imperial families are descended.

Children

| Name | Portrait | Lifespan | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charles III, Duke of Lorraine |

|

15 February 1543 – 14 May 1608 |

married 19 January 1559 Claude of Valois and had issue. |

| Renata |

%252C_1588_-_1595.jpg.webp) |

20 April 1544 – 22 May 1602 |

married 22 February 1568 William V, Duke of Bavaria and had issue. |

| Dorothea |

|

24 May 1545 – 2 June 1621 |

married firstly 26 November 1575 Eric II, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg and secondly 1597 Marc de Rye, Marquis de Varambon. No issue |

Depictions in popular culture

| External videos | |

|---|---|

_-_WGA11572.jpg.webp) | |

Television

She was portrayed by Sonya Cassidy in an episode of The Tudors.

Literature

- Helle Stangerup, In the Courts of Power, 1987.

- Marianne Malone, The Sixty-Eight Rooms, 2010.

In Other Work

She is seen as one of the paintings during the musical number "Haus of Holbein" in the hit musical Six.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Christina of Denmark |

|---|

References

- ↑ Blockmans, Wim (2002). Emperor Charles V, 1500-1558. p. 124.

- ↑ Jansen, 100-101

- ↑ Cartwright, 78-84

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Cartwright, Julia Mary (1913). Christina of Denmark, Duchess of Milan and Lorraine, 1522-1590. New York: E. P. Dutton.

- ↑ Cousin of Christina's mother, as well as step-sister and cousin of the Emperor

- ↑ State Papers Henry VIII, vol. 8, London, (1849), 17-21, 142.

- ↑ Alison Weir in The Lady in the Tower ISBN 978-0-345-45321-1 p. 296

- ↑ State Papers Henry VIII, vol. 8, London, (1849), 126-129, 21 January 1539

- ↑ Dansk Kvindebiografisk Leksikon. KVinfo.dk

- ↑ Charles de Mornay, urn:sbl:17458, Svenskt biografiskt lexikon (art av Ingvar Andersson.), hämtad 2020-08-03.

- ↑ "Holbein's Christina of Denmark". Smarthistory at Khan Academy. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ↑ "Humphrey Ocean on Holbein's 'Christina of Denmark'". National Gallery (UK). Retrieved 11 March 2013.

Sources

- (in Danish) Christina of Denmark in Dansk Kvindebiografisk Leksikon

- Julia Cartwright: Christina of Denmark. Duchess of Milan and Lorraine. 1522–1590, New York, 1913

- Jansen, Sharon L. (2002). The monstrous regiment of women: female rulers in early modern Europe. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-21341-7.

External links

![]() Media related to Christina of Denmark at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Christina of Denmark at Wikimedia Commons