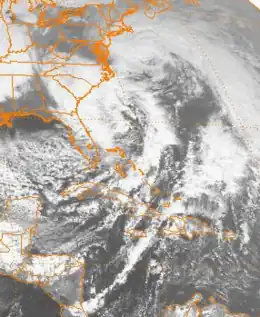

Visible image of the pair of cyclones interacting near the Eastern Seaboard from 1 p.m. EST (08:00 UTC) on December 23, 1994 | |

| Type | Nor'easter |

|---|---|

| Formed | December 22, 1994 |

| Dissipated | December 26, 1994 |

| Lowest pressure | 970 mbar (hPa) |

| Maximum snowfall or ice accretion | No snow or ice reported |

| Fatalities | 2 |

| Damage | > $21 million 1994 USD |

| Areas affected | East Coast of the United States |

The Christmas 1994 nor'easter was an intense cyclone along the East Coast of the United States and Atlantic Canada. It developed from an area of low pressure in the southeast Gulf of Mexico near the Florida Keys, and moved across the state of Florida. As it entered the warm waters of the Gulf Stream in the Atlantic Ocean, it began to rapidly intensify, exhibiting traits of a tropical system, including the formation of an eye. It attained a pressure of 970 millibars on December 23 and 24, and after moving northward, it came ashore near New York City on Christmas Eve. Because of the uncertain nature of the storm, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) did not classify it as a tropical cyclone.

Heavy rain from the developing storm contributed to significant flooding in South Carolina. Much of the rest of the East Coast was affected by high winds, coastal flooding, and beach erosion. New York State and New England bore the brunt of the storm; damage was extensive on Long Island, and in Connecticut, 130,000 households lost electric power during the storm. Widespread damage and power outages also occurred throughout Rhode Island and Massachusetts, where the storm generated 30-foot (9.1 m) waves along the coast. Because of the warm weather pattern that contributed to the storm's development, precipitation was limited to rain. Two people were killed, and damage amounted to at least $21 million.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

The storm originated in an upper-level low pressure system that moved southeastward from the central Great Plains into the Deep South of the United States. After reaching the southeast Gulf of Mexico, the disturbance underwent cyclogenesis, and the resultant system moved through Florida on December 22 in response to an approaching trough.[1] Forecasters lacked sufficient data to fully assess the cyclone for potential tropical characteristics, and as such, it could not be classified. The same trough that pushed the storm across Florida had moved to the north, allowing for high pressure to develop in the upper levels of the atmosphere.[2]

Deemed a "hybrid storm", the cyclone rapidly intensified in warm waters of up to 80 °F (27 °C) from the Gulf Stream combined with a cold air mass over the United States.[3] The system continued to rapidly intensify while moving within the Gulf Stream; it developed central convection, an unusual trait for an extratropical cyclone, and at one point exhibited an eye.[1] Despite these indications of tropical characteristics, it never was identified as tropical. On December 23 and 24, the nor'easter intensified to attain a barometric pressure of 970 mb (29 inHg).[2] An upper-level low pressure system that developed behind the storm began to intensify and grew to be larger in size than the original disturbance. In an interaction known as the Fujiwhara effect, the broad circulation of the secondary low swung the primary nor'easter northwestward towards southern New York and New England.[3] The original low passed along the south shore of Long Island, and made landfall near New York City on December 24.[4] Subsequently, it moved over southeastern New York State.[5] On December 25, the system began to rapidly weaken as it moved towards Nova Scotia, before the pair of low pressure systems moved out to sea in tandem in the early hours of December 26.[1]

Effects

Southeast United States

In South Carolina, flooding associated with the cyclone was considered to be the worst since 1943.[6] Over 5 inches (130 mm) of rainfall was reported, while winds brought down trees and ripped awnings. In addition, the coast suffered the effects of beach erosion.[7] Thousands of electric customers in the state lost power.[8] As a result of the heavy rainfall, several dams became overwhelmed by rising waters.[6] Extensive flooding of roads and highways was reported, many of which were closed as a result.[9] Up to 3 feet (0.91 m) of water flooded some homes in the region.[10] Approximately 300 people in Florence County were forced to evacuate because of the flooding, and at least 200 homes were damaged.[11] Two deaths were reported in the state. One woman was killed when her vehicle hydroplaned and struck a tree, and another person drowned after her car was struck by another vehicle.[12] Total damage in South Carolina amounted to at least $4 million.[11]

Strong winds occurred along the North Carolina coast. Diamond Shoals reported sustained winds of 45 miles per hour (72 km/h), and offshore, winds gusted to 65 miles per hour (105 km/h). On Wrightsville Beach, rough surf eroded an 8-foot (2.4 m) ledge into the beach. On Carolina Beach, dunes were breached and some roads, including portions of North Carolina Highway 12, were closed.[13]

Mid-Atlantic

As the primary storm entered New England, the secondary low produced minor coastal flooding in the Tidewater region of Virginia on December 23. Winds of 35 to 45 miles per hour (56 to 72 km/h) and tides to 1 to 3 feet (0.30 to 0.91 m) above normal were reported. In Sandbridge, Virginia Beach, Virginia, a beachfront home collapsed into the sea. Several roads throughout the region suffered minor flooding.[14] Strong winds resulting from the tight pressure gradient between the nor'easter and an area of high pressure located over the United States brought down a few utility poles, which sparked a brush fire on December 24. The fire, quickly spread by the wind, burned a field. The winds brought down several trees.[15]

Damage was light in Maryland. Some sand dunes and wooden structures were damaged, and above-normal tides occurred.[16] In New Jersey, high winds caused power outages and knocked down trees and power lines.[17] Minor coastal flooding of streets and houses was reported. Otherwise, damage in the state was minor.[18]

The storm brought heavy rainfall and high winds to New York State and New York City on December 23 and 24.[19] Gusts of 60 to 80 miles per hour (97 to 129 km/h) downed hundreds of trees and many power lines on Long Island. Several homes, in addition to many cars, sustained damage. Roughly 112,000 Long Island Lighting Company customers experienced power outages at some point during the storm.[4] As the cyclone progressed northward into New York State, high winds occurred in the Hudson Valley region. Throughout Columbia, Ulster and Rensselaer Counties, trees, tree limbs, and power lines were downed by the winds. At Stephentown, a gust of 58 miles per hour (93 km/h) was reported. Ulster County suffered substantial impacts, with large trees being uprooted and striking homes. Across eastern New York State, 25,000 households lost power as a result of the nor'easter.[5] On the North Fork of Long Island, in Southold, a seaside home partially collapsed into the water.[20]

New England

In Connecticut, the storm was described as being more significant than anticipated.[21] Gale-force wind gusts, reaching 70 miles per hour (110 km/h), blew across the state from the northeast and later from the east.[22] Trees, tree limbs, and power lines were downed, causing damage to property and vehicles. The high winds caused widespread power outages, affecting up to 130,000 electric customers. As a result, electric companies sought help from as far as Pennsylvania and Maine to restore electricity.[23] Bruno Ranniello, a spokesman for Northeast Utilities, reported that "We've had outages in virtually every community."[18] In New Haven, the nor'easter ripped three barges from their moorings. One of the barges traveled across the Long Island Sound[18] and ran aground near Port Jefferson, New York.[24] A man in Milford was killed indirectly when a tree that was partially downed by the storm fell on him during an attempt to remove it from a relative's yard. Northeast Utilities, which reported the majority of the power outages, estimated storm damage in the state to be about $6–$8 million (1994 USD; $8.8–$11.8 million 2008 USD).[23]

Effects were less severe in New Hampshire and Vermont. In southern New Hampshire, a line of thunderstorms produced torrential rainfall, causing flooding on parts of New Hampshire Route 13. Flash flooding of several tributaries feeding into the Piscataquog River was reported.[25] In Maine, the storm brought high winds and heavy rain.[26] Along the coast of southern Maine and New Hampshire, beach erosion was reported. Additionally, minor flooding was reported across the region, as a result of heavy surface runoff and small ice jams.[19] In Rhode Island, the power outages were the worst since Hurricane Bob of the 1991 Atlantic hurricane season.[27] Throughout the state, approximately 40,000 customers were without electric power. As with Massachusetts, downed trees and property damage were widespread. There were many reports of roof shingles being blown off roofs and of damage to gutters. In Warwick, several small boats were damaged after being knocked into other boats. The highest reported wind gust in the state was 74 miles per hour (119 km/h) at Ashaway, Rhode Island. Statewide damage totaled about $5 million.[28]

Massachusetts, particularly Cape Cod and Nantucket, bore the brunt of the nor'easter. Reportedly, wind gusts approached 100 miles per hour (160 km/h) on Cape Cod and, offshore, waves reached 30 feet (9.1 m).[2] At Walpole, wind gusts peaked at 88 miles per hour (142 km/h), while on Nantucket gusts of 84 miles per hour (135 km/h) were reported. The winds left 30,000 electric customers without power during the storm, primarily in the eastern part of the state. Power was out for some as long as 48 hours. Property damage was widespread and many trees, signs, and billboards were blown down. A large tent used by the New England Patriots was ripped and blown off its foundation. The winds also spread a deadly house fire in North Attleboro. Although not directly related to the storm, it caused seven fatalities.[29] Because tides were low, little coastal flooding occurred.[30] Outside the Prudential Tower Center in Boston, the storm toppled a 50-foot (15 m) Christmas tree.[31] Rainfall of 2 to 3.5 inches (51 to 89 mm) was recorded throughout the eastern part of the state, contributing to heavy runoff that washed away a 400-foot (120 m) section of a highway. Total damage in Massachusetts was estimated at about $5 million.[30]

See also

- Timeline of the 1994 Atlantic hurricane season

- 1994 Atlantic hurricane season

- Extratropical cyclone

- Subtropical cyclone

- Surface weather analysis

- Hurricane Sandy ― a tropical cyclone that took on extratropical characteristics shortly before landfall

References

- 1 2 3 "Daily Weather Maps: December 19–25, 1994". U.S. Department of Commerce. Retrieved 2006-11-19.

- 1 2 3 Robert Henson (1995). "Weatherwise, December 1995 vol. 48 # 6" (PDF). Hurricanes in disguise. Weatheranswer.com. Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- 1 2 Chris Cappella (2005-05-17). "1991's 'perfect storm' a hybrid hurricane". USA Today. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- 1 2 "High Wind Event Record Details for New York". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on 2011-05-20. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- 1 2 "High Wind Event Record Details for New York (2)". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on 2011-05-20. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- 1 2 "Heavy rains/flooding Event Report Details for South Carolina". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on 2011-05-20. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- ↑ "Thunderstorm Winds Event Report Details for South Carolina". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on 2011-05-20. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- ↑ "Winds hit Carolinas". A. The Atlanta Constitution. December 24, 1994. p. 10.

- ↑ "Heavy rains/flooding Event Report Details for South Carolina (2)". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on 2011-05-20. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- ↑ "Heavy rains/flooding Event Report Details for South Carolina (3)". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on 2011-05-20. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- 1 2 "Heavy rains/flooding Event Report Details for South Carolina (4)". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on 2011-05-20. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- ↑ Staff Writer (1994). "Rainstorm Clobbers East Coast; 2 Reported Dead, Electricity Out". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2012-10-22. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- ↑ "Flooding Event Record Details for North Carolina". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on 2011-05-20. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- ↑ "Coastal Flooding Event Record Details for Virginia". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on 2011-05-20. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- ↑ "High Wind Event Record Details for Virginia". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on 2011-05-20. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- ↑ "Coastal Flooding Event Record Details for Maryland". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on 2011-05-20. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- ↑ Steve Marlowe. "Storm Causes Power Outages for Thousands in N.J". The Record. Archived from the original on 2012-10-22. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- 1 2 3 Dennis Hevesi (1994-12-25). "Storms Darken Holiday In Connecticut and on L.I." The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- 1 2 "Mild Weather Continues". Cornell University. Archived from the original on June 11, 2007. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- ↑ "Coastal Flooding Event Record Details for New York". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on 2011-05-20. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- ↑ "Storm on East Coast Batters New England". Victoria Advocate. Associated Press. December 25, 1994. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- ↑ "Storm Pounds East Coast". The Sacramento Bee. Associated Press. 1994. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- 1 2 "High Winds Event Record Details for Connecticut". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on 2011-05-20. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- ↑ Staff Writer (1994). "Storm Batters New York, Connecticut". Daily News of Los Angeles. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- ↑ "Flash Flood Event Record Details for New Hampshire". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on 2011-05-20. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- ↑ Dave Hanson (1994). "Rain, Wind to Fade Away by Holiday Southern Maine is Warm but Wet as a Weakening Storm Moves in". Portland Press Herald. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

- ↑ "R.I. Power Outage Harder to Fix Than in '91". Boston Globe. Associated Press. 1994. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

- ↑ "High Winds Event Record Details for Rhode Island". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on 2011-05-20. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- ↑ Hart, Jordana; Lynda Gorov (1994-12-25). "7 killed in fire fed by winds in North Attleborough - Metro - The Boston Globe". Boston Globe. Retrieved 2014-12-10.

- 1 2 "High Winds Event Record Details for Massachusetts". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on 2011-05-20. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- ↑ Staff Writer (1994-12-25). "Christmas Eve Storm Batters East". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2008-10-22.