In music, chromatic mediants are "altered mediant and submediant chords."[1] A chromatic mediant relationship defined conservatively is a relationship between two sections and/or chords whose roots are related by a major third or minor third, and contain one common tone (thereby sharing the same quality, i.e. major or minor). For example, in the key of C major the diatonic mediant and submediant are E minor and A minor respectively. Their parallel majors are E major and A major. The mediants of the parallel minor of C major (C minor) are E♭ major and A♭ major. Thus, by this conservative definition, C major has four chromatic mediants: E major, A major, E♭ major, and A♭ major.

There is not complete agreement on the definition of chromatic mediant relationships. Theorists such as Allen Forte define chromatic mediants conservatively, only allowing chromatic mediant chords of the same quality (major or minor) as described above. However, he describes an even more distant "doubly-chromatic mediant" relationship shared by two chords of the opposite mode, with roots a third apart and no common tones; for example C major and E♭ or A♭ minor, and A minor and C♯ or F♯ major.[2] Other less conservative theorists, such as Benward and Saker, include these additional chords of opposite quality and no shared tones in their default definition of chromatic mediants. Thus, by this more permissive definition, C major has six chromatic mediants: E major, A major, E♭ major, A♭ major, E♭ minor and A♭ minor.

When a conservative chromatic mediant relationship involves seventh chords, "...the triad portions of the chords are both major or both minor."[3] This pertains to the more permissive definition of chromatic mediant relationships as well.

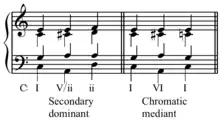

Chromatic mediants are usually in root position, may appear in either major or minor keys, usually provide color and interest while prolonging the tonic harmony, proceed from and to the tonic or less often the dominant, sometimes are preceded or followed by their own secondary dominants, or sometimes create a complete modulation.[1]

Some chromatic mediants are equivalent to altered chords, for example ♭VI is also a borrowed chord from the parallel minor, VI is also a secondary dominant of ii (V/ii), and III is V/vi, with context and analysis revealing the distinction.[1]

Chromatic mediant chords were rarely used during the baroque and classical periods, though the chromatic mediant relationship was occasionally found between sections, but the chords and relationships became much more common during the romantic period and became even more prominent in post-romantic and impressionistic music.[1] One author describes their use within phrases as, "surprising," even more so than the deceptive cadence, in part due to their rarity and in part due to their chromaticism (they come from 'outside' the key),[5] while another says they are so rare that one should first eliminate the possibility that one is looking at a diatonic movement (presumably, borrowing), then make sure that it is not a secondary chord, and then, "finally," one may consider, "the likeliness of an actual chromatic mediant relationship."[6]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Benward & Saker (2009). Music: In Theory and Practice, Vol. II, pp. 201–204. Eighth edition. ISBN 978-0-07-310188-0. "Always look carefully to determine the function of the chord."

- ↑ Forte, Allen (1979). Tonal Harmony, pp. 9, 463. 3rd edition. Holt, Rinehart, and Wilson. ISBN 0-03-020756-8. "Two triads are said to exhibit a chromatic mediant relationship if they are both major or both minor and their roots are a 3rd apart."

- ↑ Kostka, Stefan and Payne, Dorothy (1995). Tonal Harmony, p. 324. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-035874-5.

- ↑ Kostka and Payne (1995), p. 321.

- ↑ Huron, David Brian (2006). Sweet Anticipation: Music and the Psychology of Expectation, p. 271. MIT. ISBN 9780262083454.

- ↑ Sorce, Richard (1995). Music Theory for the Music Professional, p. 423. Scarecrow. ISBN 9781880157206.

- ↑ Benward and Saker (2009), p. 204