| Chunky Creek Train Wreck | |

|---|---|

| |

| Details | |

| Date | February 19, 1863 About Daybreak (c. 6:00 a.m.) |

| Location | Newton County, near Hickory, Mississippi |

| Coordinates | 32°19′08″N 88°58′20″W / 32.31889°N 88.97222°W |

| Country | United States |

| Line | Southern Rail Road Company |

| Operator | Isaiah P. Beauchamp |

| Incident type | Derailment |

| Cause | Signal Passed at Danger, Bridge Failure Leading to Derailment; Misjudgment, Fatigue, & Miscommunication |

| Statistics | |

| Trains | 1 |

| Passengers | c. 100 |

| Deaths | c. 75 |

| Injured | c. 25 |

The Chunky Creek Train Wreck occurred on February 19, 1863, when a train crashed into the creek from a bridge damaged by heavy rain on the Southern Rail Road line between Meridian and Vicksburg, Mississippi.

The line was notorious for poor repairs that were reported to have caused accidents almost daily. The train, with a tender and four or five cars, driven by Isaiah P. Beauchamp, had been carrying Confederate reinforcements to the important Vicksburg garrison. The local section-master had placed a warning sign on the track, and given instructions to stop incoming traffic, but these were not followed. The train derailed and fell into the creek, killing about 75 passengers, some others being rescued by Confederates from the nearby 1st Choctaw Battalion.

Background

Rainy weather caused severe flooding in the days before the wreck. Debris had accumulated against the bridge's supports. While the section master attempted to clear the debris, a bridge support collapsed. A missing support was likely the main cause of the wreck. Also, a day before the wreck, a train crossed the bridge, causing the bridge to submerge and, thus, causing the supports to shift out of alignment.

The Hercules and Its Cars

The engine was named the Hercules.[1][2] It likely had one tender and four cars attached. The Hercules was an American 4-4-0 type. Before the War, the Hercules was based out of New Orleans until April 1862. Isaiah P. Beauchamp, the engineer, was living in New Orleans in 1860.

In some modern accounts, the Hercules has been mislabeled as the "Mississippi Southern." The "Mississippi Southern" is a misnomer.

A telegraphic dispatch was reported the day of the crash. Joseph M. Booker sent the message to Charles Storrow Williams, superintendent of the Southern Rail Road. The telegraph mentions the name of the engine,

To C.S. WILLIAMS:

MERIDIAN, Feb. 19.—The telegraphic repairer from Newton to-day, reports the railroad badly washed between Newton and Hickory. The engine Hercules, which left here with a freight train at 4 o’clock this morning, ran into the river near the Chunkey. The engineer, fireman and a large number of the passengers are supposed to be drowned. Eight bodies have been recovered. The engine and four cars are out of sight in the water.|J.M. Booker[2]

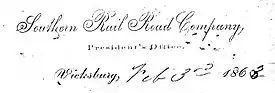

The Southern Rail Road Company

The Southern Rail Road Company was charted in 1850.[3] The line was named the Southern Rail Road.[4] The line is sometimes referred to as the "Mississippi Southern" or "Southern Mississippi."

In 1861, the Southern Rail Road ran 145 miles from Vicksburg to Meridian. It intersected with the New Orleans, Jackson & Greater Northern Rail Road at Jackson and with the Mobile & Ohio Rail Road at Meridian. The Southern Rail Road was built in a wide gauge at 5 feet apart.

The Southern Rail Road had a reputation of being the worst maintained rail road in the country. The Daily Southern Crisis, a Jackson newspaper, claimed that accidents were almost a daily occurrence on the line.[5]

Chunky Creek

The Chunky Creek begins in north Newton County. The confluence of the Chunky, Okahatta, and Potterchitto Creeks meet before the point where the Chunky River starts.

Warnings Ignored

Absalom F. Temples, the section master, attempted to halt trains by placing men near the tracks and setting up a signal.

The Section Master's Testimony

Temples' statement was found in a Jackson, Mississippi newspaper The Daily Southern Crisis,

On Monday morning after the rains of the day previous I took three hands, all I had in my employ, and with the hand car went over the whole line of my section, which is eight miles long, attending to shoving the drift from the different bridges. I was at the bridge where the accident occurred twice in the forenoon and twice in the evening. I visited the bridges four times a day, and there was no drift at all against the bridge until between nine and ten o’clock on the morning of Wednesday. Had been to this bridge four times each day. By 3 o’clock, P. M., on Wednesday, the drift had accumulated so thick and the streams so much swollen, that I could not move it with a dozen hands, had they been with me. The Chunkey was then at its highest, and the bridge had sagged down stream about six inches, where the current was the strongest. I worked there about one hour. Meantime one of the bents passed out, and with it a large portion of the drift. The evening freight train was then due and laying at the station just below. There were several men at the bridge at the time, and I asked Mr. Green Harris, one of my neighbors, to stop the approaching train, which he did, while I returned to the section house. As the train ran slowly, the conductor told me to be sure to notify the train that would leave Meridian at three the next morning, of the danger at the bridge. I said I would do so, and took my hand-car immediately and went to the water tank where Mr. Hardy, an employee of the road, was working. I told him to stop the trains at the tank and not let them pass, as the road was all torn up and two other trains were then at Hickory Station and could get no further, and that one bent was out of the bridge and they could not cross. ‘I live so far off that I cannot be here myself’ was the reply. Then I told him to be sure and keep a negro there for the purpose. I then returned to the bridge and found that the water had fallen about two inches. I then dug a hole in the middle of the track and put up a thick pole about as near as I could tell 150 yards from the bridge. This is the usual method of stopping trains when danger is ahead. Unable to do any more good I returned to the section house at dark. The next morning I had the hands up before daylight, and was just going out on the road to work, having full confidence that Hardy would not let the trains pass the tank. Just as I started out I met a man running up the road with the news of the accident. Some of them are hurt, and I told them to go up to my house and everything possible should be done for them.[6]

Accident

The locomotive Hercules was totally submerged with the attached wooden boxcars demolished. The cargo debris of barrels, boxes, and supplies could be found floating in the winter cold stream. About 75 of nearly one-hundred passengers were killed because of the high speed impact but others drowned after being trapped under the wreckage.

The Athens Post; an Athens, Tennessee newspaper; reported the following,

A man just in from Chunkey says the engine and five cars are under water.—The conductor is hurt, but swam out.—The engineer has not been heard from. Between twenty-five and fifty persons are supposed to be lost—mostly soldiers, who broke open every car in the train and got in there before leaving here. The third and fifth cars had only troops and one horse—about seventy men in the two. The engineer was forward on the engine looking out, and the conductor was on the engine.[2]

Rescue and Recovery

A Confederate camp was bivouacked near the Chunky Creek when the wreck occurred. They were likely part of John W. Pierce's 1st Choctaw Battalion who were sanctioned by the Confederacy a couple of days before the wreck.

Samuel G. Spann, a Captain at that time, was also at the camp to recruit American Indians for his anticipated command—Spann's Independent Scouts. The camp heard the call for help, and the men were ordered to "fly to the rescue!"

In an article in Confederate Veteran magazine, Spann wrote about the chaotic scene, "the engineer was under military orders, and his long train of cars was filled with Confederate soldiers, who, like the engineer, were animated with but one impulse-to Vicksburg! to victory or death! Onward rushed the engineer. All passed over except the hindmost car. The bridge had swerved out of plumb, and into the raging waters with nearly one hundred soldiers the rear car was precipitated. "Help!" was the cry, but there was no help."[7]

Spann continued in his magazine article,

The cry reached the camp. "Fly to the rescue!" was the command, and in less time than I can tell the story every Indian was at the scene. It was there that Jack Amos again displayed his courage and devotion to the Confederate soldiers. I must not omit to say, however, that with a like valor and zeal Elder [Jackson], another full-blood Indian soldier, proved equal to the emergency. Jack Amos and Elder [Jackson] both reside now in Newton County.[Jackson] is now an ordained Baptist minister, having been a gospel student under the venerable and beloved Rev. Dr. N. L. Clark, now living at Decatur, Newton County, and father of our Dr. Clark, of Meridian. Led by these two dauntless braves, every Indian present stripped and plunged into the raging river to the rescue of the drowning soldiers. Ninety-six bodies were brought out upon a prominent strip of land above the water line. Twenty-two were resuscitated and returned to their commands, and all the balance were crudely interred upon the railroad right of way, where they now lie in full view of the passing train, except nine, who were afterwards disinterred by kind friends and given a more honorable burial.[7]

A prominent local citizen survived the crash. Willis R. Norman lived near Hickory Station, Mississippi. Norman was in the car closest to the engine. He managed to swim to safety even though he was badly injured. The Daily Southern Crisis reported Norman's condition,

At the house of Mr. Temples, about a mile from the bridge, are several wounded men, amongst whom is Mr. W. R. Norman, an aged and very intelligent and prominent gentleman, who resides near [Hickory] station. He fully corroborates the statement of the other passengers in regard to the care and caution used by the conductor, before reaching the last Chunky bridge, at which time, he says, they were running faster than at any previous. When the train ran off the track, he was in the car nearest the engine, and he thinks that not more than three escaped out of that car. He went to the bottom, in about fifteen feet of water, but rose to the surface with the fragments of the broken car, and with great difficulty succeeded in getting to the shore. His collar-bone is broken, his leg badly hurt, and he is injured internally, but will recover.[6]

About a year before the wreck and in a "twist of fate," Norman was one of many Newton County citizens who petitioned the Choctaw Indians to serve in the Civil War.

Classification

This bridge disaster is classified in several categories: a signal passed at danger, a bridge failure, and a derailment.

Factors

Some factors that may explain why the train crashed includes: misjudgment, fatigue, and miscommunication.

Aftermath

For a number of days after the wreck, bodies and cargo were being recovered from the creek. Many of the bodies were interred along the railroad right-of-way and/or on Absalom F. Temple's farm.

Isaiah P. Beauchamp's body was recovered and sent to his residence at Forest, Mississippi.[6]

Cash was found in the possession of one passenger who died in the crash. William P. Grayson apparently was a lawyer and was elected a cashier for the Bank of New Orleans in the 1850s. During the War, Grayson was a Confederate purchasing agent who was responsible for procuring cotton. It was reported that he had up to $80,000 dollars.

Investigation

Lieutenant Frank J. Ames, a New Orleans native, was a secret detective and was assigned to investigate. Ames was a New Orleans police officer and had policing experience since 1859. He created reports. One particular report was read by Brigadier General John Adams regarding commissary and the names of recovered bodies.

Media

The Chunky Creek Train Wreck made newspaper headlines throughout the United and Confederate States. The Memphis Daily Appeal was based in Jackson, Mississippi at the time of the wreck. The Fayetteville Observer captured a conversation about the disaster.

Some few particulars of a terrible railroad accident on the Southern railroad yesterday, reached the city last evening, which has sent a gloom over the city in consequence of the uncertainty as to who are lost. When a passenger train was crossing Chunkey river, the bridge gave way, precipitating the engine, tandor and four cars into the water. The engineer and fire-man were killed. It is supposed a large number of passengers were drowned, as the train was, as usual, well loaded. At our latest advices eight bodies had been recovered. The accident occurred between this city and Meridian.

— The Memphis Daily Appeal, By M’clanahan & Dill., Friday, February 20, 1863

A dispatch from Jackson, dated the 20th, says that as the out freight train from Meridian came to Chunky bridge last night it gave way, precipitating the engine and four cars into the river. A large number of passengers were on the train, and from 50 to 100 are reported drowned. The bridge cannot be repaired until the water falls.

— Evening Star, Vol. XXI., Washington. D.C., February 25, 1863

On February 19, a railroad train ran into the Chunkey River. Between forty and fifty lives, mostly those of soldiers, are supposed to have been lost.

— The New-York Times, Vol. XII---No.3573., New-York, Sunday, March 8, 1863

Late Richmond papers give dispatches from Jackson, Miss., dated Feb. 20, which say as a train from Meredan [sic] came to Chunky bridge last night it gave way and precipitated the engine and four cars into the river. From 50 to 100 passengers were drowned. The bridge cannot be repaired till the water falls.

— Washington Standard, Vol. III., Olympia, Washington Territory, March 14, 1863

Traveling in the Confederacy—A Fact.

Conversation heard on Meridian and Jackson Rail Road, at Chunkey River. Dramatis Personae—Civilian and Soldier:

- Civilian—Terrible smash up! How many persons were drowned here?

- Soldier—They got out twenty eight bodies.

- Civilian—Think they are all out?

- Soldier—No.

- Civilian (struck with horror)—Why don’t they get them out?

- Soldier—Trouble, sir, trouble! By G--, sir! They wouldn’t have got the twenty eight out, but they wanted to see if they had passports, sir!

— Fayetteville Observer, Vol. XLIII., Fayetteville, North Carolina, March 23, 1863

To travel in the Confederate States, a passport was required.[8] The Confederate passport system assisted in identifying possible spies, deserters, or conscripts.[8][9][10] Passports were originally for slave identification, and many whites were offended when they were required to have passports during the War.[9]

Studies

Throughout the 20th century, several informal studies have been conducted.

Senator Pat Harrison investigated the Choctaws participation in the Civil War. He attempted to place a memorial commemorating their service.

In 1985, several ventures were made to locate the graves of the soldiers that were found along the rail road. The Lauderdale County Department of Archives & History director Jim Dawson made several trips to the Chunky Creek area.

Harold Graham and members of the Newton County Historical and Genealogical Society surveyed the wreck area for grave sites in 2004.[11]

In 2015 & 2016, historian & writer Robert Bruce Ferguson investigated the presumed wreckage area. He took a number of digital photographs for in-depth study and analysis.

Commemoration

U.C.V. Camp Dabney H. Maury attempted to place a memorial at the site of the wreck. A New Orleans newspaper wrote, "a lasting monument should be erected upon that lone burial spot that will serve to perpetuate alike the death of the Southern martyrs and the dauntless courage and fraternal heroism of the Choctaws."[12] For unknown reasons, the monument was never placed.

A small historical marker was placed at the scene of the accident on February 19, 2005.

Errata

Several incongruities have manifested in historical writings concerning the train wreck.

- Hercules[2] was the engine that crashed into the Chunky Creek in February 1863. The Hercules has been mislabeled as the "Mississippi Southern." The name "Mississippi Southern" was probably confused with the rail road company's name: Southern Rail Road Company.

- Samuel G. Spann's Confederate Veteran magazine article incorrectly placed the accident date in June 1863. By many written accounts, the accident happened at dawn on February 19, 1863.

- Spann also incorrectly identified one of the American Indian rescuers. It was Elder Jackson rather than Elder Williams who participated in the rescue and recovery.

- Some accounts refer to a "General Arnold Spann" who commanded the American Indians. These accounts highly likely refer to Major Samuel G. Spann and his American Indian scouts. A search for "General Arnold Spann" has yield negative results.

See also

References

- ↑ Ferguson, Robert. "Southeastern Indians During The Civil War". The Backwoodsman. Vol. 39, no. 2 (Mar/Apr 2018 ed.). Bandera, Texas: Charlie Richie Sr. p. 64. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 "Terrible Railroad Accident". The Athens Post. March 6, 1863.

- ↑ Bright, David L. (2002–2017). "Confederate Railroads: Southern (of Mississippi)". Retrieved October 1, 2017.

- ↑ Brown, A.J. (1894). "Chapter IX". History of Newton County, Mississippi, From 1834 to 1894. Clarion-Ledger Company. p. 68.

- ↑ "The Southern Railroad—Mail Route". The Daily Southern Crisis. February 3, 1863.

- 1 2 3 "The Railroad Disaster at Chunkey Bridge". The Daily Southern Crisis. February 26, 1863.

- 1 2 Spann, S.G. (December 1905). "Choctaw Indians As Confederate Soldiers". Confederate Veteran Magazine. XIII (12): 560 and 561.

- 1 2 "The Passport Office". The Memphis Daily Appeal. July 21, 1863.

- 1 2 Sternhell, Yael A. (2014). "Papers, Please!". Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ↑ "Soldier's passport". Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ↑ Justice, Keith L. (2015). "1863 Train Wreck Victim' Graves Remembered". Retrieved November 9, 2017.

- ↑ "Famous Indian Scout". The Times-Democrat. May 22, 1903.

Further reading

- Brown, A.J. History of Newton County, Mississippi, from 1834–1894, (Jackson, Miss.: Clarion-Ledger Company, 1894, Republished in 1964).