The Church of Zion, also known as the Church of the Apostles on Mount Zion, is a presumed Jewish-Christian congregation continuing at Mount Zion in Jerusalem in the 2nd-5th century, distinct from the main Gentile congregation which had its home at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.[1]

There have been attempts at identifying the lower, possibly Roman-period layers of the building housing the so-called "Tomb of David" and the Cenacle, as the remains of the house of worship of this presumed Jewish-Christian congregation.

Theory

Ancient sources

The reference to such a Jewish-Christian congregation comes from the Bordeaux Pilgrim (c.333), Cyril of Jerusalem (348), and Eucherius of Lyon (440), but in academia the theory originates with Bellarmino Bagatti (1976), who considered that such a church, or Judaeo-Christian synagogue, continued in what was presumed as the old "Essene Quarter".[2]

Emmanuel Testa's support for Bagatti's view led to the "Bagatti-Testa school", with the thesis that a surviving Jewish-Christian community existed in Jerusalem, and that many Jewish-Christians returned from Pella to Jerusalem after the First Jewish-Roman War and established themselves on Mount Zion.[3]

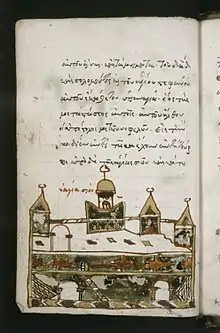

Bagatti's theory is supported by Bargil Pixner (May 1990 Biblical Archaeology Review),[4] who argues that the 6th-century Madaba Map shows two churches next to each other - the Basilica of Hagia Sion and the "Church of the Apostles", the putative Jewish-Christian synagogue of Mount Zion.[5]

Archaeological interpretations

Connected with the Bagatti-Testa theory is the 1951 interpretation by archaeologist Jacob Pinkerfeld of the lower layers of the Mount Zion structure known as David's Tomb. Pinkerfeld saw in them the remains of a synagogue which, he concluded, had later been used as a Jewish-Christian church.[6] Pinkerfeld dated the remains of the alleged synagogue to the 2nd-5th century, when Jerusalem was known under the Roman name of Aelia Capitolina.[1]

Criticism

According to Edwin K. Broadhead, the problem with the thesis of Bagatti, Testa, Pinkerfeld and Pixner is that the layers indicate a Crusader structure built directly on top of apparently perfectly preserved Roman walls.[7] Still, the fact that the alleged Roman walls align perfectly with Byzantine structures excavated in the same area is one argument in favour of dating Pinkerfeld's walls to the Byzantine period.[7] Another one is that the Holy Zion basilica was truly huge (it is the largest church depicted on the Madaba Map, and the architect of the Dormition Abbey concluded from his 1899 excavations that it measured 60 by 40 metres), making it is more likely that the walls at "David's Tomb" were part of the basilica.[7] Thirdly, the huge size of the earliest blocks from the walls, very likely recycled from Herodian buildings, fit much better with the basilica than with a small synagogue.[7]

See also

References

- 1 2 Stemberger, Günter (1999). Jews and Christians in the Holy Land: Palestine in the Fourth Century. A&C Black. p. 79. ISBN 9780567230508. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

A further attempt to locate Jewish Christians in Jerusalem is connected with the Church of Zion. The arguments that have been advanced to date for the idea that in Jerusalem a Gentile Christian congregation, the majority, had its home at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, while a Jewish Christian congregation centred on Mount Zion, represent no more than pointers.

- ↑ Studia Hierosolymitana in onore del P. Bellarmino Bagatti: Volume 1. Bellarmino Bagatti, Emmanuele Testa, Ignazio Mancini - 1976. However, not the biblical Mount Zion, but rather the "Christian" Mount Zion will be explored in this study. ... B. Bagatti and others think that the "synagogue" referred to must have been a Judeo-Christian one...

- ↑ Taylor, Joan E. (1993). Christians and the Holy Places: The Myth of Jewish Christian Origins. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 1. ISBN 9780198147855. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

According to the Bagatti-Testa school, the Jewish-Christian church was centred in Jerusalem and headed first by Peter ... Many Jewish-Christians then returned to Jerusalem after the war ended and established themselves on Mount Zion.

- ↑ Pixner BAR article, May 1990 Archived 2018-03-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Davila, James R. (2003). The Dead Sea scrolls as background to postbiblical Judaism and early Christianity: papers from an international conference at St. Andrews in 2001. Studies on the Texts of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Vol. 46. Brill Publishers. pp. 66–67. ISBN 9789004126787. ISSN 0169-9962. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

Channels of Communication: Essenes in Jerusalem? In a long series of publications since 1976 the Dominican archaeologist Bargil Pixner has been arguing the case for an Essene quarter in Jerusalem located on the southern part of the western hill, now called Mount Zion. ... headquarters of the early Jerusalem church, understood to have been the site of the Last Supper... This geography is held to support a close relationship between the Essenes of Jerusalem and the earliest Christian community.

- ↑ Elizabeth McNamer, Bargil Pixner Jesus and First-Century Christianity in Jerusalem p6 8, 2008 "In 1951, archaeologist Joseph [sic] Pinkerfield found on Mount Zion the remains of a synagogue ... Pinkerfield also found pieces of plaster with graffiti scratched on them that came from the synagogue wall. "

- 1 2 3 4 Broadhead, Edwin Keith (2010). Jewish Ways of Following Jesus: Redrawing the Religious Map of Antiquity. Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament. Vol. 266. Mohr Siebeck. p. 320. ISBN 9783161503047. ISSN 0512-1604. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

Finally, Pixner claims that the Madaba map (6th century) indicates that the Byzantine Hagia Sion was built alongside the Church of the Apostles, not over it. A key problem in the theory of Bagatti, Testa, Pinkerfeld, and Pixner is the sequence of layers. If the walls identified by Pinkerfeld are Roman era, one is left with a Crusader structure built directly on top of Roman walls. This would require that no part of the Byzantine structure remained or was used, but that the Roman walls were "remarkably well preserved."