Francesco (Cicco) Simonetta (1410 – 30 October 1480) was an Italian Renaissance statesman who composed an early treatise on cryptography.

Biography

Francesco, nicknamed Cicco, was born in Caccuri, Calabria, and received a fine education. He studied Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and other languages and graduated in civil and canonic law, presumably in Naples.

As a young man, he entered the service of the Sforza family as a secretary to condottiero Francesco Sforza and rapidly rose to the top of the administration. He was soon placed in charge of the city of Lodi.

In 1441, Francesco Sforza married Bianca Maria Visconti (1425–1468), the illegitimate daughter of Filippo Maria Visconti, 3rd Duke of Milan. On Filippo's death (1447), the so-called Ambrosian Republic had been set up in Milan by the patrician families. In 1450, Francesco Sforza, backed by the Venetians, laid siege to Milan to combat the aristocrats. The city surrendered after eight months and Francesco made himself Capitano del popolo. He was proclaimed duke by the people and by right of his wife.

Simonetta was nominated "golden knight" and entered the ducal chancellery. This appointment was the beginning of his undisputed domination of the political situation for thirty years. As a reward for his services, he was given the fief of Sartirana, in Lomellina, which he administered with competency and care. He soon became a member of the Secret Council. When he married Elisabetta Visconti in 1452 his fame was widespread.

In 1456, he received the honorary citizenship of Novara, which was later followed by those of Lodi and Parma. In 1465, he wrote the Constitutiones et Ordines as a contribution to a better organization of the chancellery, over which he now had complete control.

At the death of Francesco Sforza (1466) his son Galeazzo Maria succeeded him. His mother Bianca Maria and the other influential families did not approve of his capricious conduct of state affairs, but Simonetta sided with Galeazzo.

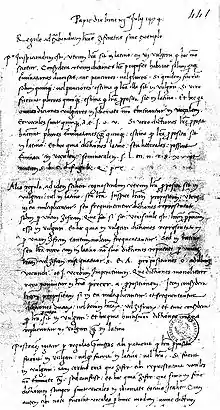

In 1474 Simonetta wrote his Rules for Decrypting Enciphered Documents Without a Key, presumably for use by his collaborators, although no evidence exists of actual utilization of these rules in the field.

In 1476, Galeazzo was assassinated and was succeeded by his 7-year-old son Gian Galeazzo. His tutor was his mother, Bona of Savoy. In this period of unrest, Simonetta's diplomatic activity was intense. He maneuvered to maintain stability in the Milanese state during the endemic conflicts between Guelphs, Ghibellines and the various wars and interstate alliances.

The next year he became ducal secretary, with the powers of a prime minister. Simonetta's power provoked the hatred of Ludovico il Moro (1452–1508), one of the younger brothers of Galeazzo, who plotted to seize the duchy. The main obstacle to his project was the presence of Simonetta in the city government. After many personal vicissitudes, Ludovico managed to gain the confidence of the duchess and convinced her to arrest Simonetta.

He was accused falsely of treason, imprisoned, and tortured in Pavia. His house and assets were pillaged, and he was beheaded in the tower of the castle. His body was buried in the cloister of Sant’Apollinare, outside the Milan city walls, to mark the end of his influence in the Milanese politics.

During the Sforza rule, the duchy had enjoyed years of prosperity and great expansion despite the political turmoil. Important buildings were erected in the cities; the farming of rice and the silk industry were introduced in agriculture. With the advent of printing Milan had become a cultural center unequaled in all Europe, until it fell into foreign hands after the death of Ludovico il Moro.

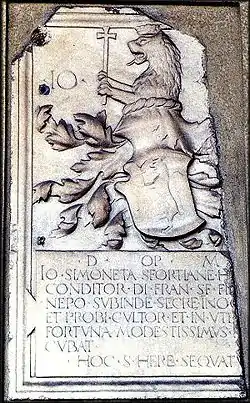

Presently a fragment of his tombstone and the name of a narrow street in Milan are the only visible testimonials of Simonetta.

Decrypting rules

Simonetta has been described in the cryptological literature as an important cryptanalyst in consideration of his rules.

His work is in reality a collection of hints for solving ciphers that were rather old-fashioned at that time. Contemporary cipher clerks were well equipped to defy the tricks he described. Nomenclators were in general use, combining small codebooks and large substitution tables with homophones and nulls.

His cipher-breaking rules are applicable to dispatches with word divisions, without homophones, nulls or code words. He says nothing of polyalphabetic substitution or the existence of nomenclators. His notes were anticipated by Leon Battista Alberti in his theoretical, but more comprehensive, treatise De Cifris, which earned him the title of Father of Western Cryptology.

It was only a century later that a scientific treatise entirely devoted to cryptanalysis was written by the French mathematician François Viète. Simonetta might have been involved in cipher work in his early career, but no evidence of such activity has been found.

References

- Buonafalce, A. “Cicco Simonetta’s Cipher-Breaking Rules”, Cryptologia XXXII: 1. 62–70. 2008.

- Colussi, P. Cicco Simonetta, Capro Espiatorio di Ludovico il Moro. Storia di Milano Vol. VII, Milano 1957.

- Natale, A. R. Ed. I Diari di Cicco Simonetta (1473–76 and 1478), Milano 1962.

- Perret, P.-M. "Les règles de Cicco Simonetta pour le déchiffrement des écritures secrètes" Paris Bibliothèque de l’École des chartes 51 (1890) 516–525.

- Pesic, P. “François Viète. Father of Modern Cryptanalysis—Two New Manuscripts”, Cryptologia XXI: 1. 1-29. 1997.

- Sacco, L., "Un Primato Italiano. La Crittografia nei Secoli XV e XVI", Bollettino dell'Istituto Storico e di Cultura dell'Arma del Genio, Roma, December 1947.

- Smith, Rev. J., Ed. The Life, Journals and Correspondence of Samuel Pepys. 275. 1841.