| Asian woolly-necked stork | |

|---|---|

| Mangaon, Raigad, Maharashtra India | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Ciconiiformes |

| Family: | Ciconiidae |

| Genus: | Ciconia |

| Species: | C. episcopus |

| Binomial name | |

| Ciconia episcopus (Boddaert, 1783) | |

The Asian woolly-necked stork or Asian woollyneck (Ciconia episcopus) is a species of large wading bird in the stork family Ciconiidae. It breeds singly, or in small loose colonies. It is distributed in a wide variety of habitats including marshes in forests, agricultural areas, and freshwater wetlands across Asia.[2][3]

Taxonomy

The woolly-necked stork was described by the French polymath Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon in 1780 in his Histoire Naturelle des Oiseaux from a specimen collected from the Coromandel Coast of India.[4] The bird was also illustrated in a hand-coloured plate engraved by François-Nicolas Martinet in the Planches Enluminées D'Histoire Naturelle which was produced under the supervision of Edme-Louis Daubenton to accompany Buffon's text.[5] Neither the plate caption nor Buffon's description included a scientific name but in 1783 the Dutch naturalist Pieter Boddaert coined the binomial name Ardea episcopus in his catalogue of the Planches Enluminées.[6] The woolly-necked stork is now placed in the genus Ciconia that was erected by the French zoologist Mathurin Jacques Brisson in 1760.[7][8] The genus name Ciconia is the Latin word for a "stork"; the specific epithet episcopus is Latin for "bishop".[9]

Two subspecies are recognised:[8]

- C. e. episcopus (Boddaert, 1783) – India to Indochina, the Philippines and Malay Peninsula, north Sumatra

- C. e. neglecta (Finsch, 1904) – south Sumatra, Java, Lesser Sunda Islands, Sulawesi

The online edition of the Handbook of the Birds of the World , the IOC, Clements, and the IUCN have reclassified the African race, C. e. microscelis, as a separate species, the African woolly-necked stork (C. microscelis),[10][11] with the remaining two subspecies becoming the Asian woolly-necked stork.[12] The Handbook and other sources of taxonomic lists use geographical separation as the sole basis for elevating the three subspecies into two species, and this assumption requires to be tested using more definitive methods such as genetics.

Description

The woolly-necked stork is a medium-sized stork at 75–92 cm tall.[13] The iris is deep crimson or wine-red. The stork is glistening black overall with a black "skull cap", a downy white neck which gives it its name. The lower belly and under-tail coverts are white, standing out from the rest of the dark coloured plumage. Feathers on the fore-neck are iridescent with a coppery-purple tinge. These feathers are elongated and can be erected during displays. The tail is deeply forked and is white, usually covered by the black long under tail coverts. It has long red legs and a heavy, blackish bill, though some specimens have largely dark-red bills with only the basal one-third being black. Sexes are alike. Juvenile birds are duller versions of the adult with a feathered forehead that is sometimes streaked black-and-white.[14] The African birds are described as having the edges of the black cap diffused or with a jagged border compared to a sharp and clean border in the Asian birds. Sexes are identical, though males are thought to be larger.[13] When the wings are opened either during displays or for flight, a narrow band of very bright unfeathered skin is visible along the underside of the forearm. This band has been variously described as being "neon, orange-red", "like a red-gold jewel", and "almost glowing" when seen at close range.[13][15][16]

Small nestlings are pale grey with buffy down on the neck, and a black crown. At fledging age, the immature bird is identical to the adult except for a feathered forehead, much lesser iridescence on feathers, and much longer and fluffier feathers on the neck.[13][14][17] Newly fledged young have a prominent white mark in the center of the forehead that can be used to distinguish young of the year.[2]

English common names for this species include the white-necked stork, white-headed stork, bishop stork and parson-bird. More recently, the African and Asian populations are considered to be two different species, the African woolly-necked stork and the Asian woolly-necked stork. This is based purely on geographical isolation,[18] but there is no morphological or phylogenetic evidence yet to support this split.[2]

Distribution and habitat

It is a widespread tropical species which breeds in Asia, from India to Indonesia.[3] It is a resident breeder building nests on trees located on agricultural fields or wetlands, on natural cliffs, and on cell phone towers.[13][19][20][21] They use a variety of freshwater wetlands including seasonal and perennial reservoirs and marshes, crop lands, irrigation canals and rivers, but are mostly seen in agricultural areas and in wetlands outside protected areas across south Asia and Myanmar.[2][13][22][23][24] They are attracted to fires in grasslands and crop fields where they capture insects trying to escape the fire.[13] They use ponds and marshes inside forests in Asia, especially in south-east Asia where they use grassy and marshy areas in clearings in several forest types.[13][24] In India, they are an uncommon species in coastal habitats.[17] They use coastal areas in Asia with birds in Sulawesi observed to be eating sea snakes.[13] In an agricultural landscape in north India, woolly-necked storks preferred fallow fields during the summer and monsoon seasons, and natural freshwater wetlands during the winter.[22] Here, irrigation canals were preferentially used during winters when water levels were low, and birds avoided crop fields in all seasons. Assisted by construction of new irrigation canals, this species is spreading to arid areas like the Thar Desert in Rajasthan, India.[25] Across south Asia, Asian woolly-necked storks largely use agricultural landscapes with more numbers seen using unprotected wetlands relative to the amount of wetlands on the landscape, and a majority of individuals use agricultural crops.[2][24][26] In Haryana, north India, they nest on trees planted along crop fields and irrigation canals as part of traditional multifunctional agroforestry and generally avoid trees close to human settlements.[27]

Individuals of this species have been sighted at altitudes of 3,790 m above sea level in China (Napahai wetland),[28] and 3,540 m above sea level in Nepal (Annapurna Conservation Area).[29]

Behaviour

Several calls by adult birds have been described including bisyllabic whistles given along with displays at the nest,[30] and a fierce hissing sound when a bird was attacked by a trained falcon.[13] The woolly-necked stork is a broad winged soaring bird, which relies on moving between thermals of hot air for sustained long-distance flight. Like all storks, it flies with its neck outstretched. It has also been observed to 'roll, tumble and dive at steep angles' in the air with the wind through its quills making a loud noise.[31] Adult birds have also been observed diving from nests before flying away abruptly in a 'bat-like flight'.[13]

This species is largely seen as single birds, in pairs, or in small family groups of 4–5. While flocks are uncommon, they occur in all parts of the distribution range of the species and can be seen in all seasons.[2][22][26] Flocking is affected by different factors in different areas. In more arid areas, most of the flocks occur in the summer when few wetlands are remaining,[23] whereas in areas with more water, flocks occur largely in winter after chicks have fledged from nests.[22] However, on agricultural landscapes, artificial irrigation introduces considerable complexity in providing water throughout the year, and flocks occur throughout the year.[26] They often associate with wintering stork species including the Black and White Storks.[23]

Asian woolly-necked storks using south Asian agricultural landscapes showcased changing seasonal behaviors consistent with altering landscape conditions. Storks changed their most preferred habitats (relative to availability of each habitat) from natural wetlands in the winter to dry fallow fields in the summer, and actively avoided (used much less relative to available) flooded rice paddies.[22] Analogous to this change of preferred habitat seasonally, Asian woolly-necked storks in lowland Nepal spent less time foraging (suggesting higher efficiency of finding food) during the winter relative to monsoon when rice paddies was the dominant crop.[32] These two observations suggest that Asian woolly-necked storks preferred drier crops as foraging habitats, and its foraging efficiency improved in less wet crops. Additionally, storks in Nepal did not alter behaviors from foraging to the energy expending alert behaviors when they were close to farmers, though time spent being alert reduced considerably while foraging in wetland habitats.[32] This suggests that the storks do not view farmers are a significant threat. Activity budgets of woolly-necked storks in lowland Nepal were identical to that recorded for similar storks in protected and managed reserves suggesting that south Asian croplands provide considerable benefits as suitable foraging areas with minimal disturbances by farmers to large water birds such as Asian woolly-necked storks.[32]

Diet

The Asian woolly-necked stork walks slowly and steadily on the ground seeking its prey, which like that of most of its relatives, consists of amphibians, reptiles and insects.[13][15][16]

Breeding

Typically, a large stick nest is built on a tree, and clutch size is two to six eggs, with five and six eggs being less common.[2][14][33][27] Birds use both forest trees and scattered trees in agricultural areas to build nests.[19][27] In India, some nests have been being observed in or near urban areas on cell phone towers, but such nesting on artificial human-made structures is not a regular occurrence.[20][27][34][35] Riverside cliffs are occasionally used for nesting.[21][33]

In Haryana, north India, nesting woolly-necked storks used trees close to irrigation canals and far from human habitation for nesting, and were not affected by the presence of natural wetlands and relatively larger patches of trees on the landscape.[27] Very few nests each year were placed on artificial structures such as electricity pylons, and the majority were placed on Dalbergia sissoo, Ficus religiosa and Eucalyptus sp. In Haryana's agricultural landscape, small numbers of woolly-necked stork nests were also found on Acacia nilotica, Azadirachta indica, Mangifera indica, Mitragyna parviflora, Syzhygium cumini and Tectona gradis.[27] Asian woolly-necked storks reused over 44% of nest sites for multiple years.[27] Brood size of 42 successful nests in Haryana was relatively high with over three chicks successfully fledging from nests, and a small number of nests each year fledging four and five chicks each with six chicks fledging from one nest.[2][27] Detailed observations of breeding habits in north India suggest that the woolly-necked stork is not an obligate wetland species unlike other stork species that locate their nests close to wetlands.

Two nests of woolly-necked storks were reused after stork chicks had fledged by black kites Milvus migrans in lowland Nepal.[36] Asian woolly-necked stork nests in Haryana were preferentially reused by dusky eagle-owls Bubo coromandus over other large nests made by other bird species in the area.[37] It seems likely that Asian woolly-necked storks support the well-being of many other species, including large raptors such as dusky eagle-owls, via commensal and other inter-species relationships associated with their nests.

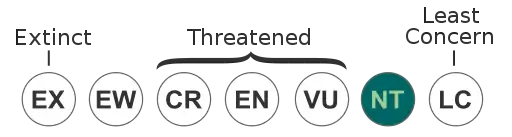

Conservation

The species was elevated from "Near-threatened" to "Vulnerable" in 2014 based on anecdotal reports of deforestation in south-east Asia potentially leading to catastrophic population declines with the assumption that the species required protected wetlands inside forested reserves.[2] It was, however, down listed to "Near-threatened" in 2019 after concrete evidence emerged from south Asia and Myanmar that the erstwhile population estimate was a severe underestimate, and that most woolly-necked storks used agricultural areas and unprotected wetlands, with abundances being lower inside forested reserves.[2] Agricultural landscapes in north India support considerable numbers of breeding pairs that have relatively large brood sizes and behaviors similar to storks in protected managed reserves suggesting that this species is not an obligate wetland bird and that it is not reliant on undisturbed protected wetlands and forest reserves.[27][32] An earlier "guesstimate" of the south and south-east Asian population of woolly-necked storks of 25,000 has been revised upwards to an estimated > 2,00,000 storks in south Asia alone.[26]

Counts carried out along the Mekong river in Cambodia (first survey in 2006 an 2007, followed by another in 2018) showed some variations in numbers of Woolly-necked Storks counted.[38] These variations may have been due to differences in count methods and season making it difficult to know if population sizes of this species has changed along the River Mekong.[38] Modeled distributions of woolly-necked storks strongly overlapped forested reserves in south-east Asia suggesting low ability to survive outside forests in stark contrast to the situation in south Asia and Myanmar.[3][24][32] The majority of the protected reserve forests and wetlands in south-east Asia are under threat suggesting that woolly-necked storks face an uncertain future in this region.

Different views & aspects

_with_Black-headed_Ibises_W2_IMG_9730.jpg.webp)

_taking_off_from_the_fields_near_Hodal_I.jpg.webp)

_02.jpg.webp) Flying in Chitwan National Park, Nepal.

Flying in Chitwan National Park, Nepal.

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2020). "Ciconia episcopus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T22727255A175530482. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22727255A175530482.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Sundar, K.S. Gopi (2020). "Woolly-necked Stork - a species ignored" (PDF). SIS Conservation. 2: 33–41. eISSN 2710-1142. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-04-12. Retrieved 2021-04-12.

- 1 2 3 Gula, Jonah; Sundar, K.S. Gopi; Dean, W. Richard J. (2020). "Known and potential distributions of the African Ciconia microscelis and Asian C. episcopus Woollyneck Storks" (PDF). SIS Conservation. 2. eISSN 2710-1142.

- ↑ Buffon, Georges-Louis Leclerc de (1780). "Le héron violet". Histoire Naturelle des Oiseaux (in French). Vol. 14. Paris: De L'Imprimerie Royale. p. 91.

- ↑ Buffon, Georges-Louis Leclerc de; Martinet, François-Nicolas; Daubenton, Edme-Louis; Daubenton, Louis-Jean-Marie (1765–1783). "Heron, de la côte de Coromandel". Planches Enluminées D'Histoire Naturelle. Vol. 10. Paris: De L'Imprimerie Royale. Plate 906.

- ↑ Boddaert, Pieter (1783). Table des planches enluminéez d'histoire naturelle de M. D'Aubenton : avec les denominations de M.M. de Buffon, Brisson, Edwards, Linnaeus et Latham, precedé d'une notice des principaux ouvrages zoologiques enluminés (in French). Utrecht. p. 54, Number 906.

- ↑ Brisson, Mathurin Jacques (1760). Ornithologie, ou, Méthode Contenant la Division des Oiseaux en Ordres, Sections, Genres, Especes & leurs Variétés (in French and Latin). Paris: Jean-Baptiste Bauche. Vol. 1, p. 48, Vol. 5, p. 361.

- 1 2 Gill, Frank; Donsker, David, eds. (2019). "Storks, frigatebirds, boobies, cormorants, darters". World Bird List Version 9.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ↑ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 107, 147. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ↑ del Hoyo, J.; Collar, N.; Garcia, E.F.J. (2019). del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; Sargatal, J.; Christie, D.A.; de Juana, E. (eds.). "African Woollyneck (Ciconia microscelis)". Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ↑ "Storks, frigatebirds, boobies, darters, cormorants – IOC World Bird List". www.worldbirdnames.org. Retrieved 2023-02-03.

- ↑ Elliott, A.; Garcia, E.J.F.; Boesman, P.; Kirwan, G.M. (2019). del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; Sargatal, J.; Christie, D.A.; de Juana, E. (eds.). "Asian Woollyneck (Ciconia episcopus)". Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Hancock, James A.; Kushlan, James A.; Kahl, M. Philip (1992). Storks, Ibises and Spoonbills of the World. London, U.K.: Academic Press. pp. 81–86. ISBN 978-0-12-322730-0.

- 1 2 3 Scott, J. A. (1975). "Observations on the Breeding of the Woollynecked Stork". Ostrich. 46 (3): 201–207. doi:10.1080/00306525.1975.9639519. ISSN 0030-6525.

- 1 2 Legge, W. V. A history of the birds of Ceylon. Ceylon: Tisaria, Deliwala. p. 234.

- 1 2 Meyer, A. B.; Wiglesworth, L. W. (1898). The birds of Celebes, vol. 2. Berlin: Friedlander. p. 809.

- 1 2 Ali, S.; Ripley, S. D. (1968). Handbook of the birds of India and Pakistan, vol. I. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 98.

- ↑ del Hoyo, J.; Collar, N. J. (2014). BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World. Volume 1. Non-passerines. Lynx Edicions. ISBN 978-84-96553-94-1.

- 1 2 Choudhary, D.N.; Ghosh, T.K.; Mandal, J.N.; Rohitashwa, Rahul; Mandal, Subhatt Kumar (2013). "Observations on the breeding of the Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia episcopus in Bhagalpur, Bihar, India". Indian Birds. 8 (4): 93–94.

- 1 2 Vaghela, U; Sawant, D.; Bhagwat, V. (2015). "Woolly-necked Storks Ciconia episcopus nesting on mobile-towers in Pune, Maharashtra". Indian Birds. 10 (6): 154–155.

- 1 2 Rahmani, A. R.; Singh, B. (1996). "Whitenecked or Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia episcopus (Boddaert) nesting on cliffs". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 93 (2): 293–294.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sundar, K. S. Gopi (2006). "Flock Size, Density and Habitat Selection of Four Large Waterbirds Species in an Agricultural Landscape in Uttar Pradesh, India: Implications for Management". Waterbirds: The International Journal of Waterbird Biology. 29 (3): 365–374. doi:10.1675/1524-4695(2006)29[365:fsdahs]2.0.co;2. JSTOR 4132592. S2CID 198154724.

- 1 2 3 Pande, S.; Sant, N.; Bhate, R.; Ponkshe, A.; Pandit, P.; Pawashe, A.; Joglekar, C. (2007). "Recent records of wintering White Ciconia ciconia and Black C. nigra storks and flocking behaviour of White-necked Storks C. episcopus in Maharashtra and Karnataka states, India" (PDF). Indian Birds. 3 (1): 28–32.

- 1 2 3 4 Win, Myo Sander; Yi, Ah Mar; Myint, Theingi Soe; Khine, Kaythy; Po, Hele Swe; Non, Kyaik Swe; Sundar, K. S. Gopi (2020). "Comparing abundance and habitat use of Woolly-necked Storks Ciconia episcopus inside and outside protected areas in Myanmar" (PDF). SIS Conservation. 2: 96–103. eISSN 2710-1142.

- ↑ Singh, H. (2015). "Asian Woollyneck Ciconia episcopus breeding in western Rajasthan, India". BirdingASIA. 24: 130–131.

- 1 2 3 4 Kittur, Swati; Sundar, K.S. Gopi (2020). "Density, flock size and habitat preference of Woolly-necked Storks Ciconia episcopus in agricultural landscapes of south Asia" (PDF). SIS Conservation. 2: 71–79. eISSN 2710-1142.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Kittur, Swati; Sundar, K. S. Gopi (2021). "Of irrigation canals and multifunctional agroforestry: Traditional agriculture facilitates Woolly-necked Stork breeding in a north Indian agricultural landscape". Global Ecology and Conservation. 30: e01793. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01793. S2CID 239153561.

- ↑ Burnham, James W.; Wood, Eric M. (2012). "Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia episcopus at Napahai wetland, Yunnan, China". Forktail. 28: 158–159.

- ↑ Ghale, T. R.; Karmacharya, Dikpal K. (2018). "A new altitudinal record for Asian Woollyneck Ciconia episcopus in South Asia". BirdingASIA. 29: 96–97.

- ↑ Kahl, M. P. (1972). "Comparative ethology of the Ciconiidae. Part 4. The 'typical' storks (genera Ciconia, Sphenorhynchus, Dissoura, and Euxenura)". Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie. 30 (3): 225–252. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1972.tb00852.x. S2CID 82008004.

- ↑ Bannerman, D. A. (1953). The birds of west and equatorial Africa. Vol. 1. London: Oliver and Boyd. p. 171.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ghimire, Prashant; Pandey, Nabin; Timilsina, Yajna P.; Bist, Bhuwan S.; Sundar, K. S. Gopi (2021). "Woolly-necked Stork (Ciconia episcopus) Activity Budget in Lowland Nepal's Farmlands: The Influence of Wetlands, Seasonal Crops, and Human Proximity". Waterbirds: The International Journal of Waterbird Biology. 44 (4): 415–424.

- 1 2 Vyas, R.; Tomar, R. S. (2006). "Rare clutch size and nesting site of Woolynecked Stork (Ciconia episcopus) in Chambal River Valley". Newsletter for Birdwatchers. 46 (6): 95.

- ↑ Greeshma, P.; Nair, Riju, P.; Jayson, E.A.; Manoj, K.; Arya, V.; Shonith, E.G. (2018). "Breeding of Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia episcopus in Bharathapuzha river basin, Kerala, India". Indian Birds. 14 (3): 86–87.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Tere, Anika (2021). "Breeding of Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia episcopus at Dhaniyavi, near Vadodara". Flamingo Gujarat. XIX-1: 1–4.

- ↑ Ghimire, Prashant; Pandey, Nabin; Belbase, Bibek; Ghimire, Rojina; Khanal, Chiranjeevi; Bist, Bhuwan Singh; Bhusal, Krishna Prasad (2020). "If you go, I'll stay: nest use interaction between Asian Woollyneck Ciconia episcopus and Black Kite Milvus migrans in Nepal". BirdingASIA. 33: 103–105.

- ↑ Sundar, K S Gopi; Ahlawat, Rakesh; Dalal, Devender Singh; Kittur, Swati (2022). "Does the stork bring home the owl? Dusky Eagle-Owls Bubo coromandus breeding on Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia episcopus nests". Biotropica. 54 (3): 561–565. doi:10.1111/btp.13086. S2CID 247823196.

- 1 2 Mittermeier, J. C.; Sandvig, E. M.; Jocque, M. (2019). "Surveys in 2018 along the Mekong river, northern Kratie province, Cambodia, indicate a decade of declines in populations of threatened bird species". BirdingASIA. 832: 80–89.

External links

- Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia episcopus - BirdLife International

- Woolly-necked Stork videos and photos - Internet Bird Collection