Clara (c. 1738 – 14 April 1758) was a female Indian rhinoceros who became famous during 17 years of touring Europe in the mid-18th century. She arrived in Europe in Rotterdam in 1741, becoming the fifth living rhinoceros to be seen in Europe in modern times since Dürer's Rhinoceros in 1515. She was known as the Dutch rhinoceros and received the name Miss Clara in the German town of Würzburg in August 1748. After tours through towns in the Dutch Republic, the Holy Roman Empire, Switzerland, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, France, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, the Papal States, Bohemia and Denmark, she died in Lambeth, England.

In 1739, she was drawn and engraved by two English artists. She was then brought to Amsterdam, where Jan Wandelaar made two engravings that were published in 1747. In the subsequent years, the rhinoceros was exhibited in several European cities. In 1748, Johann Elias Ridinger made an etching of her in Augsburg, and Petrus Camper modelled her in clay in Leiden. In 1749, Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon drew her in Paris. In 1751, Pietro Longhi painted her in Venice.[1]

Life

In 1738, aged approximately one month, Clara was adopted by Jan Albert Sichterman in India after her mother was killed by Indian hunters somewhere in Assam. Sichterman was the director of the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie or VOC) in Bengal. She became quite tame, and was allowed to move freely around his residence. In 1740, Sichterman either sold or gave her as a gift to Douwe Mout van der Meer, captain of the Knappenhof, who returned to the Netherlands with Clara.[2] Captain Van der Meer would become Clara's agent and companion until her death.

Clara disembarked at Rotterdam on 22 July 1741 and was immediately exhibited to the public. Clara was exhibited in Antwerp and Brussels in 1743 and in Hamburg in 1744. The exhibitions were so successful that Douwe Mout van der Meer left the VOC in 1744 to tour Europe with his rhinoceros. He had a special wooden carriage built to convey her, which had at least eight horses pulling it.[3] The carriage had only a small window in order to people would be encouraged to pay to see her.[3] Her skin was kept moist with fish oil. The tour started in earnest in spring 1746, and proved to be an outstanding success. Clara visited Hanover and Berlin, where King Frederick II of Prussia saw her on 26 April in Spittelmarkt. The tour continued to Frankfurt an der Oder, Breslau, and Vienna, where Emperor Francis I and Empress Maria-Theresa saw her on 5 November.

In 1747, she travelled to Regensburg, Freiberg and Dresden, where she posed for Johann Joachim Kaendler from the Meissen porcelain factory and was visited on 19 April by Augustus III, Elector of Saxony and King of Poland. She was in Leipzig on 23 April for Easter, and visited the orangery of the castle of Kassel at the invitation of Frederick II, Landgrave of Hesse. In November she visited the "Gasthof zum Pfau" (The Peacock Inn) in Mannheim, and she was in Strasbourg in December for Christmas.

In 1748, she visited Bern, Zürich, Basel, Schaffhausen, Stuttgart, Augsburg, Nuremberg and Würzburg. She returned to Leiden and visited France. She was in Reims in December 1748, and was received by King Louis XV in January 1749 at the royal menagerie in Versailles. She spent 5 months in Paris, creating a sensation: letters, poems, and songs were written about her, and wigs were created à la rhinocéros. Clara was examined by the naturalist Buffon, Jean-Baptiste Oudry painted a life-size portrait of her, and she inspired the French Navy to name a vessel Rhinocéros in 1751. A drawing based on Oudry's painting appeared in Diderot and D'Alembert's Encyclopédie, and Buffon's Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière.

At the end of 1749, Clara embarked at Marseilles to travel to Italy. Avoiding the fate of Dürer's Rhinoceros, which drowned in a shipwreck off the Ligurian coast near Porto Venere in 1516, Clara visited Naples and Rome. In March 1750, she visited the Baths of Diocletian. She seems to have rubbed off her horn while in Rome (a common problem for rhinoceroses kept in close confinement, although some reports claim that her horn was cut off in Rome for reasons of safety). A new horn eventually grew in.

She passed through Bologna in August and Milan in October. She arrived in Venice in January 1751, where she became a major attraction at the carnival and was painted by Pietro Longhi. She passed through Verona on the way back to Vienna. She had reached London by the end of the year, where she was viewed by the British royal family.

Little is known of her exact movements from 1752 to 1758. In March 1752, she travelled to Ghent in the Austrian Netherlands, followed by Lille.[4] Afterwards she visited Prague, then Warsaw, Kraków, Danzig and Breslau (a second time) in 1754; and Copenhagen in 1755. She returned to London in 1758, where she was exhibited at the Horse and Groom in Lambeth, with entry prices of sixpence and one shilling. This was where she died on 14 April, aged about 20.

Honors and recognitions

In 1991, the Natuurhistorisch Museum in Rotterdam held an exhibition on Clara. In 2008 the Clara Memorial was created at the same museum to mark the 250th death anniversary of the rhinoceros.[2]

Gallery

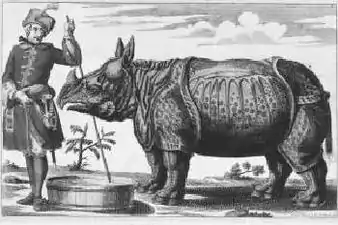

Clara, the rhinoceros, that travelled throughout Europe in the mid-18th century. Engraving by Elias Baeck from 1746.

Clara, the rhinoceros, that travelled throughout Europe in the mid-18th century. Engraving by Elias Baeck from 1746. Charles Grignion the Elder after Jan Wandelaar Engraving of Clara and a human skeleton for Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani. of Albinus, Bernhard Siegried, 1697-1770. Marked Tab IV. Artist: Wandelaar, Jan, 1690-1759. (1749)

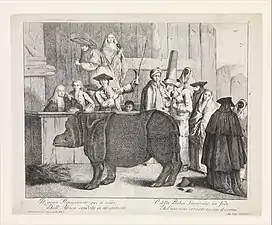

Charles Grignion the Elder after Jan Wandelaar Engraving of Clara and a human skeleton for Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani. of Albinus, Bernhard Siegried, 1697-1770. Marked Tab IV. Artist: Wandelaar, Jan, 1690-1759. (1749) Clara, painted by Pietro Longhi in Venice in 1751. One onlooker is holding her horn, rubbed off (or removed) in Rome the previous year.

Clara, painted by Pietro Longhi in Venice in 1751. One onlooker is holding her horn, rubbed off (or removed) in Rome the previous year. Alessandro Longhi Etching (after 1751)

Alessandro Longhi Etching (after 1751) Rhinoceros in Venice circle of Pietro Longhi (1751)

Rhinoceros in Venice circle of Pietro Longhi (1751) Rear part of the rhinoceros Clara, Circle of Lorenzo Baldissera Tiepolo, ca. 1751

Rear part of the rhinoceros Clara, Circle of Lorenzo Baldissera Tiepolo, ca. 1751

References

- ↑ Rookmaaker, L. C. (1973). "Captive rhinoceroses in Europe from 1500 until 1810" (PDF). Bijdragen tot de Dierkunde. 43 (1): 39–63. doi:10.1163/26660644-04301002.

- 1 2 van der Pol, Bauke. THe Dutch East India Company in India. Parragon Books Ltd. p. 67.68. ISBN 978-1-4723-7605-3.

- 1 2 Vogt, Fabian. "Wie das Nashorn Clara zum Superstar des 18. Jahrhunderts wurde". Neue Zürcher Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 2022-10-27.

- ↑ Gazette van Gendt, 23/03/1752

Further reading

External links

- 1747 print of Clara at the Rijksmuseum

- Exhibition of Jean-Baptiste Oudry's works at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles from 1 May to 2 September 2007, where Oudry's painting of Clara, on loan from the Staatliches Museum Schwerin and newly restored, is on public view for the first time in 150 years