Clarence Ransom Edwards | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 1, 1859 Cleveland, Ohio, United States |

| Died | February 14, 1931 (aged 72) Boston, Massachusetts, United States |

| Buried | Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia, United States |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1883–1922 |

| Rank | |

| Service number | 0-36 |

| Unit | |

| Commands held | 6th Brigade 1st Hawaiian Brigade 26th Division 2nd Brigade First Corps Area |

| Battles/wars | Spanish–American War Philippine–American War World War I |

| Awards | Army Distinguished Service Medal Silver Star (3) Philippine Campaign Medal World War I Victory Medal Légion d'honneur (France) Croix de Guerre (France) Order of Leopold (Belgium) |

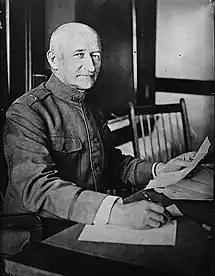

Major General Clarence Ransom Edwards (January 1, 1859 – February 14, 1931) was a senior United States Army officer, known as the first Chief of the Bureau of Insular Affairs, and commander of the 26th Division in World War I.

Early career

Edwards was born in Cleveland, Ohio, the son of local merchant William Edwards, and Lucia Ransom.[1] He graduated from the United States Military Academy (USMA) at West Point, New York, in 1883, and, due to his deficiency in math and science, was ranked last in his class (52nd of 52).[2][3] Upon his graduation from West Point, Edwards was appointed a second lieutenant in the United States Army Infantry Branch, serving with the 23rd Infantry Regiment. For the next several years Edwards served at various posts, including Fort Union, Fort Porter, Cleveland, Ohio (commanding the guard at the tomb of President Garfield), and Fort Davis. While stationed at Fort Porter he met Bessie Rochester Porter, a member of the family that included Peter Buell Porter, for whom the fort was named, and they were married in 1889.[4]

He was promoted to first lieutenant on February 25, 1891[5] while serving on detached service as Professor of Military Science and Tactics at St. John's College (now known as Fordham University), from which he received an Honorary degree. Following another stint of detached service in the Military Information Bureau of the Adjutant General's Office, Edwards returned to the 23rd Infantry at Fort Clark, serving as a captain in command of a rifle company, and later as regimental quartermaster.[6]

Spanish–American War, the Philippines, and after

At the outbreak of the Spanish–American War, Edwards moved with his regiment to New Orleans, Louisiana. In May 1898, he was given the rank of major, U. S. Volunteers, and assigned as Adjutant General of the 4th Army Corps at Mobile, Alabama (and, later, Tampa, Florida, and Huntsville, Alabama) under the command of Major General John J. Coppinger. The 4th Army Corps was to have been part of the invasion of Cuba, but was unable to obtain transport.[7]

In January 1899, Edwards was appointed adjutant-general on General H. W. Lawton's staff, accompanying him to the Philippines. He participated in all of Lawton's campaigns in the Philippines, including the Battle of Santa Cruz and the Battle of Zapote Bridge. Edwards received three silver citation stars for gallantry in action during these campaigns.[5][8] Lawton was killed in the Battle of Paye in December 1899, and Edwards accompanied his remains to Washington, D.C., for burial.[7]

In 1900, due in part to his knowledge of the conditions in the Philippines, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and named Chief of the Division of Customs and Insular Affairs in the War Department. In July 1902 he was promoted to colonel and named the first chief of the new Bureau of Insular Affairs. He retained this office until 1912, by which time he had risen to the rank of brigadier general.[9][10]

Edwards was named commander of the 6th Brigade at Fort D. A. Russell, Wyoming in October 1912. The brigade was moved to Texas City, Texas, in February 1913 in response to the Mexican Revolution. In February 1914, Edwards became the commander of the 1st Hawaiian Brigade, at Schofield Barracks, Hawaii. He then served as commander of all U. S. forces in the Panama Canal Zone from February 1915 to April 1917.[9]

World War I

Upon the outbreak of World War I, Edwards was placed in charge of the Department of the Northeast, comprising all the New England states.[10] In August 1917, four months after the American entry into the war, he was promoted to the rank of major general in the National Army and given the task of organizing the 26th Division. The division was an Army National Guard formation and arrived on the Western Front, the main theater of war, in September 1917, the first complete American division to do so.[11] The 26th Division also became the first complete American division to go into combat at Chemin-des-Dames, France, in February 1918, where they remained for 46 days.[12]

Going back to his days at West Point, Edwards had earned a reputation for being sharp-tongued and contentious. General John Joseph "Blackjack" Pershing, Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C) of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) on the Western Front, in particular despised him.[13] Edwards made another enemy in Major General Robert Lee Bullard during the 26th Division's relief of Bullard's 1st Division near Toul in April 1918. Edwards found fault with everything he saw, and accused the 1st Division of leaving behind classified documents. Bullard was enraged, but General Pershing always favored the 1st Division, and reassured him, and nothing came of the incident.[14] In July 1918, during the Second Battle of the Marne, the I Corps commander, Major General Hunter Liggett found that, although the 26th Division did not lack for heroism and fought valiantly, he could not depend on its commanders, especially Edwards, to subjugate his unit to Regular Army divisions.[15]

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Edwards' final demise came in October 1918, when he reported an incident to Liggett involving information two of his soldiers had obtained from German soldiers with whom they had been fraternizing. The Germans had expressed their belief that the war would be over soon, and that they were reluctant to continue fighting. While Edwards thought he was reporting the enemy's poor morale to Liggett, he instead gave Liggett an excuse to get rid of Edwards for his zeal in supporting the National Guard. Liggett reported the incident to the AEF commander, General Pershing, who took the opportunity to act on his personal vendetta and relieve Edwards of his command.[16] His successor was Brigadier General Frank E. Bamford, formerly the commander of the 1st Division's 2nd Brigade of the 1st Division who had been informed that he would be getting, apparently, "the worst division in the AEF." Somewhat strangely, Edwards, who had a history of saying whatever was on his mind, did not say anything at all about his dismissal from command, choosing instead to simply say nothing.[17]

World War I came to an end soon afterwards on November 11, 1918, due to the Armistice with Germany.

Later career

On Edwards' return to the United States, he was assigned to the command of the Northeastern Department once again, with headquarters in Boston. In September 1920, he reverted to his Regular Army rank of brigadier general, and was placed in command of the 2nd Brigade, based at Camp Taylor, Kentucky. He was promoted to major general in the Regular Army in June 1921, and given the command of the First Corps Area, headquartered in Boston, where he served until he retired on December 1, 1922, after nearly 40 years of service. Following retirement, Edwards served as president of the grocery company his father had founded.[7]

Edwards was a member of the Military Order of Foreign Wars (MOFW) and served as its Commander General from 1923–1926.

His daughter Bessie died from pneumonia at Camp Meade, Maryland on October 13, 1918, and his wife died January 25, 1929.[1][7] Edwards died February 14, 1931, in Boston, Massachusetts, and all three are buried together at Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Virginia.[18][7]

Honors and awards

Military decorations and medals

- Army Distinguished Service Medal (posthumous – presented in 1937)

- Spanish War Service Medal

- Philippine Campaign Medal with three silver citation stars

- Victory Medal

- Legion of Honor (France)

- Croix de Guerre with palm (France)

- Grand Cross Order of Leopold (Belgium)

- Haller Swords (Poland)[1]

Distinguished Service Medal citation

Citation

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pride in presenting the Army Distinguished Service Medal (Posthumously) to Major General Clarence R. Edwards, United States Army, for exceptionally meritorious and distinguished services to the Government of the United States, in a duty of great responsibility during World War I. After having organized the 26th Division, General Edwards commanded it with distinction during all but 18 days of its active service at the front. The high qualities of leadership and unfailing devotion to duty displayed by him were responsible for the marked espirit and morale of his command. To his marked tactical ability and energy are largely due the brilliant successes achieved by the 26th National Guard Division during its operations against the enemy from 4 February 1918 to 11 November 1918.[8]

Other honors

- Edwards received honorary Doctor of Laws degrees from Syracuse University, Trinity College, Syracuse University, Middlebury College, Boston College, Norwich College, and Fordham College.[7]

- A collection of his papers is archived at the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston, and is open for research.

Dates of rank

| Insignia[19] | Rank[19] | Component[19] | Date[19] |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | Cadet | United States Military Academy | 1 September 1879 |

| None in 1888 | Second Lieutenant | Regular Army | 13 June 1883 |

| First Lieutenant | Regular Army | 25 February 1891 | |

| Major | Volunteers | 12 May 1898 | |

| Captain | Regular Army | 30 July 1898 | |

| Lieutenant Colonel | Volunteers | 17 August 1899 (Appointment accepted on 1 October 1899. Discharged from Volunteers on 2 July 1901.) | |

| Colonel | Temporary | 1 July 1902 (Appointed as Chief of Bureau of Insular Affairs.) | |

| Brigadier General | Temporary | 30 June 1906 (Chief of Bureau of Insular Affairs.) | |

| Brigadier General | Regular Army | 12 May 1912 | |

| Major General | National Army | 5 August 1917 | |

| Brigadier General | Regular Army | 1 July 1920 | |

| Major General | Regular Army | 5 March 1921 | |

| Major General | Retired List | 1 December 1922 |

Legacy

%252C_July_2021.jpg.webp)

- A middle school in Charlestown, Massachusetts, is named in his honor.

- A statue of Edwards stands on the grounds of the Connecticut state capitol.[20]

- The General Edwards Bridge carries Massachusetts Route 1A into Lynn, Massachusetts.[21]

- Edwards Parade is located on the campus of Fordham University.[22]

- Camp Edwards, a training camp for the Massachusetts National Guard located in Falmouth, Massachusetts, was named for him in 1938.[23]

- There is a monument to Edwards in Rutland, Vermont; located at the intersection of South Main and Washington Streets, it was installed in 1934 by the third national reunion of the 26th "Yankee" Division.[24]

- General Edward's evening dress uniform is in the museum collection of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 National Cyclopaedia of American Biography, Vol. A. New York: James T. White & Company. pp. 417–419.

- ↑ "Last In Their Class: Custer, Pickett and the Goats of West Point". Lastintheirclass. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ↑ Zabecki & Mastriano 2020, p. 243.

- ↑ Zabecki & Mastriano 2020, p. 243−244.

- 1 2 Davis 1998, pp. 81, 118.

- ↑ Holden, Edward S., ed. (1901). Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York Since its Establishment in 1802, Supplement, Vol. IV 1890–1900. Cambridge: The Riverside Press. pp. 383–384.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sixty-Second Annual Report of the Association of Graduates of the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. The Lakeside Press. June 10, 1931. p. 199.

- 1 2 "Clarence Ransom Edwards". Hall of Valor. Military Times. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- 1 2 Robinson, Wirt, ed. (1920). Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U. S. Military Academy at West Point, New York Since its Establishment in 1802, Supplement, Vol. VI-A 1910–1920. Saginaw, Michigan: Seeman & Peters, Printers. p. 137.

- 1 2 Zabecki & Mastriano 2020, p. 244.

- ↑ Zabecki & Mastriano 2020, p. 245.

- ↑ Benwell, Harry A. (1919). History of the Yankee Division. Boston: The Cornhill Company. pp. 11–31. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ↑ Cooke 1997, pp. 79–80.

- ↑ Eisenhower, John S. D.; Joanne Thompson Eisenhower (2001). Yanks – The Epic Story of the American Army in World War I. New York: The Free Press. pp. 84–85, 122. ISBN 0-684-86304-9.

- ↑ Coffman, Edward M. (1968). The War to End All Wars – The American Military Experience in World War I (1998 ed.). University Press of Kentucky. pp. 250–253. ISBN 0-8131-2096-9.

- ↑ Keene, Jennifer D. (2001). Doughboys, the Great War, and the Remaking of America. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 113–115. ISBN 0-8018-6592-1.

- ↑ Zabecki & Mastriano 2020, p. 250–251.

- ↑ "Burial Detail: Edwards, Bessie P. (Section 3, Grave 4073)". ANC Explorer. Arlington National Cemetery. (Official website).

- 1 2 3 4 Official Register of Commissioned Officers of the United States Army. 1924. pg. 684.

- ↑ "Connecticut State Capitol Tours". League of Women Voters of Connecticut, Inc. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ↑ "Google Map Showing the General Edwards Bridge". Google Maps. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ↑ "Edwards Parade". Fordham University. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ↑ "Camp Edwards History". Massachusetts National Guard. Archived from the original on May 1, 2009. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- ↑ American Legion Memorials (2017). "Major General Clarence Edwards". Legion.org. Indianapolis, IN: The American Legion. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

Bibliography

- Shay, Michael E. (2011). Revered Commander, Maligned General: The Life of Clarence Ransom Edwards, 1859–1931. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri.

- Sibley, Frank P. (1919). With the Yankee Division in France. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- Taylor, Emerson Gifford (1920). New England in France, 1917–1919 – A History of the Twenty-Sixth Division U.S.A. Cambridge: Whiteside Press. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- Davis, Henry Blaine Jr. (1998). Generals in Khaki. Raleigh, NC: Pentland Press. ISBN 1571970886. OCLC 40298151.

- Zabecki, David T.; Mastriano, Douglas V., eds. (2020). Pershing's Lieutenants: American Military Leadership in World War I. New York, NY: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4728-3863-6.

- Cooke, James J. (1997). Pershing and his Generals: Command and Staff in the AEF. Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-95363-7.