Clement XIV | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Rome | |

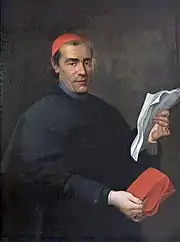

.jpg.webp) Portrait by Giovanni Domenico Porta, c. 1770 (oil on canvas, 70 x 58.5 cm,

Acquapendente city museum) | |

| Church | Catholic Church |

| Papacy began | 19 May 1769 |

| Papacy ended | 22 September 1774 |

| Predecessor | Clement XIII |

| Successor | Pius VI |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | c. 1731 |

| Consecration | 28 May 1769 by Federico Marcello Lante Montefeltro Della Rovere |

| Created cardinal | 24 September 1759 by Clement XIII |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Giovanni Vincenzo Antonio Ganganelli 31 October 1705 |

| Died | 22 September 1774 (aged 68) Rome, Papal States |

| Buried | Santi Apostoli, Rome |

| Previous post(s) |

|

| Coat of arms |  |

| Other popes named Clement | |

Pope Clement XIV (Latin: Clemens XIV; Italian: Clemente XIV; 31 October 1705 – 22 September 1774), born Giovanni Vincenzo Antonio Ganganelli, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 May 1769 to his death in September 1774. At the time of his election, he was the only Franciscan friar in the College of Cardinals, having been a member of OFM Conventual. He is the most recent pope to take the pontifical name of "Clement" upon his election.

During his pontificate, Clement decreed the suppression of the Society of Jesus.

Early life

Ganganelli was born in Santarcangelo di Romagna in 1705[1] as the second child of Lorenzo Ganganelli and Angela Serafina Maria Mazza. He received the sacrament of baptism on 2 November 1705.

He initially studied at Verucchio but later received his education from the Society of Jesus at Rimini from 1717. He also studied with the Piarists of Urbino. Ganganelli entered the Order of Friars Minor Conventual on 15 May 1723 in Forlì, taking the name Lorenzo Francesco. He did his novitiate in Urbino where his cousin Vincenzo was a friar. He was professed as a full member of that order on 18 May 1724. He was sent to the convents of Pesaro, Fano, and Recanati from 1724 to 1728 where he did his theological studies. He continued his studies in Rome under Antonio Lucci and obtained his doctorate in theology in 1731.[2]

Priesthood and cardinalate

He was ordained around this time after he received his doctorate and he taught philosophy and theology for almost a decade in Ascoli, Bologna, and Milan. He later returned to Rome as the regent of the college that he studied at and was later elected as the Definitor General of the order in 1741.[1] In the general chapters of his order in 1753 and 1756, he declined the generalship of his order and some rumored it was due to his desire of a higher office.[2]

Ganganelli became a friend of Pope Benedict XIV, who in 1758 appointed him to investigate the issue of the traditional blood libel regarding the Jews, which Ganganelli found to be untrue.[3]

Pope Clement XIII elevated Ganganelli to the cardinalate on 24 September 1759 and appointed him as the Cardinal-Priest of San Lorenzo in Panisperna. His elevation came at the insistence of Lorenzo Ricci, who was the Superior-General of the Society of Jesus.

Ganganelli opted to become the Cardinal-Priest of Ss. XII Apostoli in 1762.[4] In 1768 he was named the "ponens" of the cause of beatification of Juan de Palafox y Mendoza.[2]

Election to the papacy

Political pressures

The papal conclave in 1769 was almost completely dominated by the problem of the Society of Jesus. During the previous pontificate, the Jesuits had been expelled from Portugal and from all the courts of the House of Bourbon, which included France, Spain, Naples, and Parma. In January, 1769, these powers made a formal demand for the dissolution of the Society. Clement XIII had planned a consistory to discuss the matter, but died on 2 February, the night before it was to be held.[5]

Now the general suppression of the order was urged by the faction called the "court cardinals", who were opposed by the diminished pro-Jesuit faction, the Zelanti ("zealous"), who were generally opposed to the encroaching secularism of the Enlightenment.[1] Much of the early activity was pro forma as the members waited for the arrival of those cardinals who had indicated that they would attend. The conclave had been sitting since 15 February 1769, heavily influenced by the political maneuvers of the ambassadors of Catholic sovereigns who were opposed to the Jesuits.

Some of the pressure was subtle. On 15 March, Emperor Joseph II (1765–90) visited Rome to join his brother Leopold, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, who had arrived on 6 March. The next day, after touring St. Peter's Basilica, they took advantage of the conclave doors being opened to admit Cardinal Girolamo Spinola to enter as well. They were shown, upon the Emperor's request, the ballots, the chalice into which they would be placed, and where they would later be burned. That evening Gaetano Duca Cesarini hosted a party. It was the middle of Passion Week.[5]

The minister of King Louis XV of France (1715–74), the duc de Choiseul, had extensive experience dealing with the church as the French ambassador to the Holy See and was Europe's most skilled diplomat. "When one has a favour to ask of a Pope", he wrote, "and one is determined to obtain it, one must ask for two". Choiseul's suggestion was advanced to the other ambassadors and it was that they should press, in addition to the Jesuit issue, territorial claims upon the Patrimony of Saint Peter, including the return of Avignon and the Comtat Venaissin to France, the duchies of Benevento and Pontecorvo to Spain, an extension of territory adjoining the Papal States to Naples, and an immediate and final settlement of the vexed question of Parma and Piacenza that had occasioned a diplomatic rift between Austria and Pope Clement XIII.

Election

By 18 May, the court coalition appeared to be unravelling as the respective representatives began to negotiate separately with different cardinals. The French ambassador had earlier suggested that any acceptable candidate be required to put in writing that he would abolish the Jesuits. The idea was largely dismissed as a violation of canon law. Spain still insisted that a firm commitment should be given, though not necessarily in writing. However, such concessions could be immediately nullified by the pope upon election. On 19 May 1769, Cardinal Ganganelli was elected as a compromise candidate largely due to support of the Bourbon courts, which had expected that he would suppress the Society of Jesus. Ganganelli, who had been educated by Jesuits, gave no commitment, but indicated that he thought the dissolution was possible.[6] He took the pontifical name of "Clement XIV". Ganganelli first received episcopal consecration in the Vatican on 28 May 1769 by Cardinal Federico Marcello Lante and was crowned as pope on 4 June 1769 by the cardinal protodeacon Alessandro Albani. He was replaced as Cardinal-Priest by Buenaventura Fernández de Córdoba Spínola.[7]

Pontificate

Clement XIV's policies were calculated from the outset to smooth the breaches with the Catholic crowns that had developed during the previous pontificate. The dispute between the temporal and the spiritual Catholic authorities was perceived as a threat by Church authority, and Clement XIV worked towards reconciliation with the European sovereigns.[1] By yielding the papal claims to Parma, Clement XIV obtained the restitution of Avignon and Benevento and in general he succeeded in placing the relations of the spiritual and the temporal authorities on a friendlier footing. The pontiff went on to suppress the Jesuits, writing the decree to this effect in November 1772 and signing it on 21 July 1773.[9]

Relations with the Jews

His accession was welcomed by the Jewish community who trusted that the man who, as councilor of the Holy Office, declared them, in a memorandum issued 21 March 1758, innocent of the slanderous blood accusation, would be no less just and humane toward them on the throne of Catholicism. Assigned by Pope Benedict XIV to investigate a charge against the Jews of Yanopol, Poland, Ganganelli not only refuted the claim, but showed that most of the similar claims since the thirteenth century were groundless. He deferred somewhat on the already beatified Simon of Trent, in 1475, and Andreas of Rinn, but took the length of time before their beatifications as indicative that the veracity of the accusations raised significant doubts.

Suppression of the Jesuits

The Jesuits had been expelled from Brazil (1754), Portugal (1759), France (1764), Spain and its colonies (1767), and Parma (1768). With the accession of a new pope, the Bourbon monarchs pressed for the Society's total suppression. Clement XIV tried to placate their enemies by apparent unfriendly treatment of the Jesuits: he refused to meet the superior general, Lorenzo Ricci, removed it from the administration of the Irish and Roman Colleges, and ordered them not to receive novices, etc.[10]

The pressure kept building up to the point that Catholic countries were threatening to break away from the Church. Clement XIV ultimately yielded "in the name of peace of the Church and to avoid a secession in Europe" and suppressed the Society of Jesus by the brief Dominus ac Redemptor of 21 July 1773.[11] However, in non-Catholic nations, particularly in Prussia and Russia, where papal authority was not recognized, the order was ignored. It was a result of a series of political moves rather than a theological controversy.[12]

Mozart

Pope Clement XIV and the customs of the Catholic Church in Rome are described in letters of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and of his father Leopold Mozart, written from Rome in April and May 1770 during their tour of Italy. Leopold found the upper clergy offensively haughty, but was received, with his son, by the pope, where Wolfgang demonstrated an amazing feat of musical memory. The papal chapel was famous for performing a Miserere mei, Deus by the 17th-century composer Gregorio Allegri, whose music was not to be copied outside of the chapel on pain of excommunication. The 14-year-old Wolfgang was able to transcribe the composition in its entirety after a single hearing. Clement made the young Mozart a knight of the Order of the Golden Spur.[13]

Similarly, in 1774 German composer, Georg Joseph Vogler was also made a Knight of the Order of the Golden Militia.[14]

Activities

Clement XIV elevated sixteen new cardinals into the cardinalate in twelve consistories including Giovanni Angelo Braschi,[15] who succeeded him as Pope Pius VI.

The pope held no canonizations in his pontificate but he beatified a number of individuals.[16]

- 4 June 1769: Francis Caracciolo[17]

- 16 September 1769: Giuliana Puricelli from Busto Arsizio, Bernard of Baden[18] & Catherine of Pallanza[19]

- 1771: Tommaso Bellacci

- 14 December 1771: Martyrs of Otranto

- 8 June 1772: Paul Burali d'Arezzo

- 29 August 1772: John dal Bastone

- 1773: Pope Benedict XI (formal beatification after Pope Clement XII confirmed the cultus)

- 1774: Beatrix of Este the Younger

Death and burial

The last months of Clement XIV's life were embittered by his failures and he seemed always to be in sorrow because of this. His work was hardly accomplished before Clement XIV, whose usual constitution was quite vigorous, fell into a languishing sickness, generally attributed to poison.[20] No conclusive evidence of poisoning was ever produced. The claims that the Pope was poisoned were denied by those closest to him, and as the Annual Register for 1774 stated, he was over 70 and had been in ill health for some time.[21]

On 10 September 1774, he was bedridden and received Extreme Unction on 21 September 1774. It is said that St. Alphonsus Liguori assisted Clement XIV in his last hours by the gift of bilocation and was during two days in extasis in his bishopric in Arienzo.[22][23]

Clement XIV died on 22 September 1774, execrated by the Ultramontane party but widely mourned by his subjects for his popular administration of the Papal States. When his body was opened for the autopsy, the doctors ascribed his death to scorbutic and hemorrhoidal dispositions of long standing that were aggravated by excessive labour and the habit of provoking artificial perspiration even in the greatest heat.[1] His Neoclassical style tomb was designed and sculpted by Antonio Canova, and it is found in the church of Santi Apostoli in Rome. To this day, he is best remembered for his suppression of the Jesuits.[24]

The Monthly Review spoke highly of Ganganelli.[25] In a review of a "Sketch of the Life and Government of Pope Clement XIV", the 1786 English Review said it was clearly written by an ex-Jesuit and noted the malignant characterization of a man it described as "...a liberal, affable, ingenious man; …a politician enlarged in his views, and equally bold and dexterous in the means, by which he executed his designs."[26]

The 1876 Encyclopædia Britannica says that:

[N]o Pope has better merited the title of a virtuous man, or has given a more perfect example of integrity, unselfishness, and aversion to nepotism. Notwithstanding his monastic education, he proved himself a statesman, a scholar, an amateur of physical science, and an accomplished man of the world. As Pope Leo X (1513–21) indicates the manner in which the Papacy might have been reconciled with the Renaissance had the Reformation never taken place, so Ganganelli exemplifies the type of Pope which the modern world might have learned to accept if the movement towards free thought could, as Voltaire wished, have been confined to the aristocracy of intellect. In both cases the requisite condition was unattainable; neither in the 16th nor in the 18th century has it been practicable to set bounds to the spirit of inquiry otherwise than by fire and sword, and Ganganelli's successors have been driven into assuming a position analogous to that of Popes Paul IV (1555–59) and Pius V (1566–72) in the age of the Reformation. The estrangement between the secular and the spiritual authority which Ganganelli strove to avert is now irreparable, and his pontificate remains an exceptional episode in the general history of the Papacy, and a proof how little the logical sequence of events can be modified by the virtues and abilities of an individual.

Jacques Cretineau-Joly, however, wrote a critical history of the Pope's administration.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Wilhelm, Joseph. "Pope Clement XIV." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. 5 Jan. 2015".

- 1 2 3 "Ganganelli, O.F.M. Conv., Lorenzo (1705–1774)". Cardinals of the Holy Roman Church. Archived from the original on 28 January 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ↑ "Ganganelli, Lorenzo. "The Ritual Murder Libel and the Jew", (Cecil Roth ed.), The Woburn Press, 1934" (PDF).

- ↑ Adams, John Paul. "Clement XIV", CSUN, January 17, 2010

- 1 2 "Adams, John Paul. "Sede Vacante 1769", California State University Northridge, 4 June 2015".

- ↑ ""19 May 1769 - Ganganelli elected Pope Clement XIV, suppressor of the Jesuits", Jesuit Restoration 1814, 19 May 2015". Archived from the original on 8 January 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- ↑ Cheney, David M. (2019), "San Lorenzo in Panisperna", Catholic-Hierarchy, retrieved 9 August 2019

- ↑ F. Gligora. I papi. p. 266.

- ↑

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Pollen John, Hungerford (1912). "The Suppression of the Jesuits (1750–1773)". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Pollen John, Hungerford (1912). "The Suppression of the Jesuits (1750–1773)". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑ "McCoog SJ, Thomas M., "Jesuit Restoration - Part Two: The Society under Clement XIV", Thinking Faith, 14 August 2014".

- ↑ "The Suppression of the Jesuits by Pope Clement XIV," The Catholic American Quarterly Review, Vol. XIII, 1888.

- ↑ Roehner, Bertrand M. (1997). "Jesuits and the State: A Comparative Study of their Expulsions (1590–1990)". Religion. 27 (2): 165–182. doi:10.1006/reli.1996.0048.

- ↑ Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Mozart's Letters, Mozart's Life: Selected Letters, transl. Robert Spaethling, (W. W. Norton & Company Inc., 2000), 17.

- ↑ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Vogler, Georg Joseph". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 171–172.

- ↑

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Ott, Michael (1911). "Pope Pius VI". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 12. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Ott, Michael (1911). "Pope Pius VI". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 12. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑ "Beatifications in the Pontificate of Pope Clement XIV". GCatholic.org. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ↑ "Capetola C.R.M., Fr. Nicholas, "History", Adorno Fathers".

- ↑ ""Bernhard von Baden soll heiliggesprochen warden", Badische Zeitung 15 January 2011". 9 January 2011.

- ↑ Antonio Rimoldi. "Blessed Caterina of Pallanza Moriggi". Santi e Beati.

- ↑ "Death by poisoning of His Holiness Pope Clement XIV". Leeds Intelligencer. 15 November 1774. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019 – via The Yorkshire Post - On This Day, 15 November 2006.

- ↑ XIV, Pope Clement (1812). Interesting Letters of Pope Clement XIV. Ganganelli. To which are Prefixed, Anecdotes of His Life: Translated from the French Edition, Published at Paris by Lottin, Jun. In Four Volumes, ... William Baynes.

- ↑ "Bilocazione". Scienza di confine.eu. October 2009. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ↑ "Bilocazione". Istituto di ricerca della coscienza. 13 June 2017. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ↑ "Vatican City | History, Map, Flag, Location, Population, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ↑ "The Monthly Review Or Literary Journal Enlarged, Volume 56, Porter, 1776, p. 531". 1776.

- ↑ "The English Review, Or, An Abstract of English and Foreign Literature, J. Murray, 1786, p. 440". 1786.

References

Baynes, T. S., ed. (1878). "Clement". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. V (9th ed.). New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

Baynes, T. S., ed. (1878). "Clement". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. V (9th ed.). New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.- Collier, Theodore Freylinghuysen (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 487.

- Valérie Pirie, 1965. The Triple Crown: An Account of the Papal Conclaves from the Fifteenth Century to Modern Times Spring Books, London

External links

- The Death of a Weak and Regretful Pope: September 22, 1774 at Catholic Text Book Project

- Beach, Chandler B., ed. (1914). . . Chicago: F. E. Compton and Co.