| Industry | Steel |

|---|---|

| Predecessor | Sambre-Escaut Trefilerie et ses Derives Société Anonyme des Usines Métallurgiques du Hainaut Usine d'Athus Espérance-Longdoz Forges de la Providence Ougrée-Marihaye |

| Founded | 1981 |

| Defunct | 1999 |

| Fate | Bought by Usinor, which later became part of Arcelor |

| Successor | Usinor |

| Headquarters | Belgium |

Cockerill-Sambre was a group of Belgian steel manufacturers headquartered in Seraing, on the river Meuse, and in Charleroi, on the river Sambre. The Cockerill-Sambre group was formed in 1981 by the merger of two Belgian steel groups – SA Cockerill-Ougrée based at Seraing in the province of Liège, and Hainaut-Sambre based at Charleroi in the province of Hainaut – both being the result of post-World War II consolidations of the Belgian steel industry.

The company inherited a steel industry with significant debts and production overcapacity based on blast furnace production rather than electric furnace recycling, with numerous factory sites in constrained city locations, and adversely affected by competition in the export market from new steel-producing countries (such as South Korea and Brasil). The need to streamline was complicated by regional dependence on employment in the steel industry.

It was merged into Usinor in 1999, and after 2002 was part of the Arcelor group. As of 2010, the bulk of the group is part of the ArcelorMittal multinational steel group, where it is known as ArcelorMittal Liège.

History

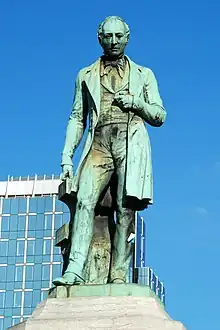

Cockerill

The Cockerill group's name came from the English-born Belgian industrialist John Cockerill, who founded John Cockerill & Cie. in 1817. During the first few decades of its existence, the firm rose to become a major integrated steel company, not only producing iron in blast furnaces, but also producing machines and other articles from the metal. After John Cockerill's death in 1840, the company became the state-owned Société anonyme John Cockerill, and an international-scale producer of iron and steel metal and products.

The 8 day Strike of the 100,000 originated at Cockerill on 10 May 1941, and eventually spread across the entirety of Liege province. The strike was both a way of seeking higher wages, and passively resisting the German occupation of Belgium during World War II. The strike was settled following an 8% wage increase, and future wartime strikes were often repressed by force.[1]

In 1955 the company merged with Ougrée-Marihaye and Ferblatil[note 1][2] to form Cockerill-Ougrée. The new company had a total steel production of over 2 million tonnes, and it employed over 45,000 people in 1957.[3]

In 1961 Tolmatil became part of Cockerill-Ougrée,[4][note 2] in 1962 it participated in the founding of Sidmar contributing 1bn Belgian francs of the companies 4.5bn capital.[4] Further consolidation of companies occurred in 1966 when it merged with Les Forges de la Providence, a Belgian steelmaker with plants in northern France with three steel plants; in Réhon[5] and Hautmont, (France) and in Marchienne-au-Pont, (Belgium) adding over 35,000 persons to the company. The new company was named Cockerill-Ougrée-Providence, and had a production capacity of 5 million tonnes of steel.[3]

In 1969 the Phenix Works (Flémalle-Haute) became part of the Cockerill-Ougrée-Providence group (fully absorbed 1989).[6][7][8]

In 1970 the company merged with the Liège-based Société Métallurgique d'Espérance Longdoz, forming Cockerill-Ougrée-Providence et Espérance Longdoz;[9] the new group was the fifth largest steelmaker in the EEC, with a steel production capacity of 7million tonnes; the new group contained all the steel producing companies in the Liège basin.[3]

In 1975 the company sold its 25% stake in Sidmar to Arbed.[10] In 1979 the Forges de la Providence company was sold to Thy-Marcinelle et Monceau (TMM), disposing of the group's interests outside the Liège area;[11] the resulting Liège-based group being known simply as Cockerill.

The company then merged with the Charleroi-based steel group Hainaut-Sambre in 1981 to form Cockerill-Sambre.[12][6]

Cockerill-Sambre

The merger to form Cockerill-Sambre was announced on 16 January 1981,[13] and the company came into being on 26 June 1981.[14] The company inherited a debt equivalent to 1363million Eur from Cockerill and a similar amount from Hainaut-Sambre.[15] A rescue plan was drawn up by consultant Jean Gandois in 1983,[16] the aim was to return the company by 1985, which was a prerequisite for sanction by the European Commission of a government-backed investment plan (the second Claes plan).[17] One consequence of the restructuring was that, of 22,000 workers (1983), nearly 8,000 would no longer be required by 1986, in addition to production cuts and closures.[18]

EKO Stahl (Eisenhüttenstadt) was acquired in 1994.[6]

In 1999 the group became part of the French steel group Usinor; in 2002 there was another merger, this time with Arbed and Aceralia of Luxembourg and Spain, to form the continental western European steel giant Arcelor.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Ferblatil: Laminoirs à Froid de Fer-blanc à Tilleur, Cold rolling and tinplate production

- ↑ Tolmatil: based in Tilleur, production of grain orientated magnetic steels for electrical applications. Source: Paul Mingret, Quelques problèmes de l'Europe à travers l'exemple de Liège et de sa région, p. 8

References

- ↑ Dictionnaire de la Seconde Guerre Mondiale en Belgique. 2008. ISBN 978-2-87495-001-8.

- ↑ Mommen 1994, p. 91.

- 1 2 3 Fusulier, Vandewattyne & Lomba 2003, p. 61

- 1 2 Mény & Wright 1987, p. 693

- ↑ "La Providence – Réhon (France)". industrie.lu (in French).

- 1 2 3 "ArcelorMittal Liège : Historique" (in French). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ↑ Mény & Wright 1987, p. 694.

- ↑ "Paul Borgnet et la société Phénix Works" (PDF), Le bulletin de la MMIL (in French) (3): 2, 2015

- ↑ "Société Métallurgique d'Espérance Longdoz , Seraing / Liége". industrie.lu (in French).

- ↑ Mény & Wright 1987, p. 695.

- ↑ Mény & Wright 1987, p. 698.

- ↑ "Cockerill Sambre Group -- Company History". fundinguniverse.com.

- ↑ Fusulier, Vandewattyne & Lomba 2003, p. 83.

- ↑ Mény & Wright 1987, p. 717.

- ↑ Fusulier, Vandewattyne & Lomba 2003, p.97 note.65 (to p. 83).

- ↑ Mény & Wright 1987, p. 726.

- ↑ Mény & Wright 1987, p. 722.

- ↑ Mény & Wright 1987, p. 728.

Sources

- Suzanne Pasleau (2002–2003). "Caractéristiques des bassins industriels dans l'Eurégio Meuse-Rhin". Fédéralisme Régionalisme (in French). 3. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- Mény, Yves; Wright, Vincent, eds. (1987). The Politics of steel: Western Europe and the steel industry in the crisis years (1974-1984). Walter de Gruyter.

- Mingret, Paul (1962). "Quelques problèmes de l'Europe à travers l'exemple de Liège et de sa région". Revue de Géographie de Lyon (in French). 37 (37–1): 5–74. doi:10.3406/geoca.1962.1734.

- Fusulier, Bernard; Vandewattyne, Jean; Lomba, Cédric (2003). Kaléidoscope d'une modernisation industrielle. Usinor-Cockrill Sambre-Arcelor (in French). Presses univ. de Louvain. ISBN 9782930344126.

- Mommen, André (1994). The Belgian economy in the twentieth century. Routledge. ISBN 9780415019361.

External links

- ArcelorMittal Liège company website – current entity

- Harold Hfinster, "Cockerill Sambre Liège / Seraing", hfinster.de

- Documents and clippings about Cockerill-Sambre in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW